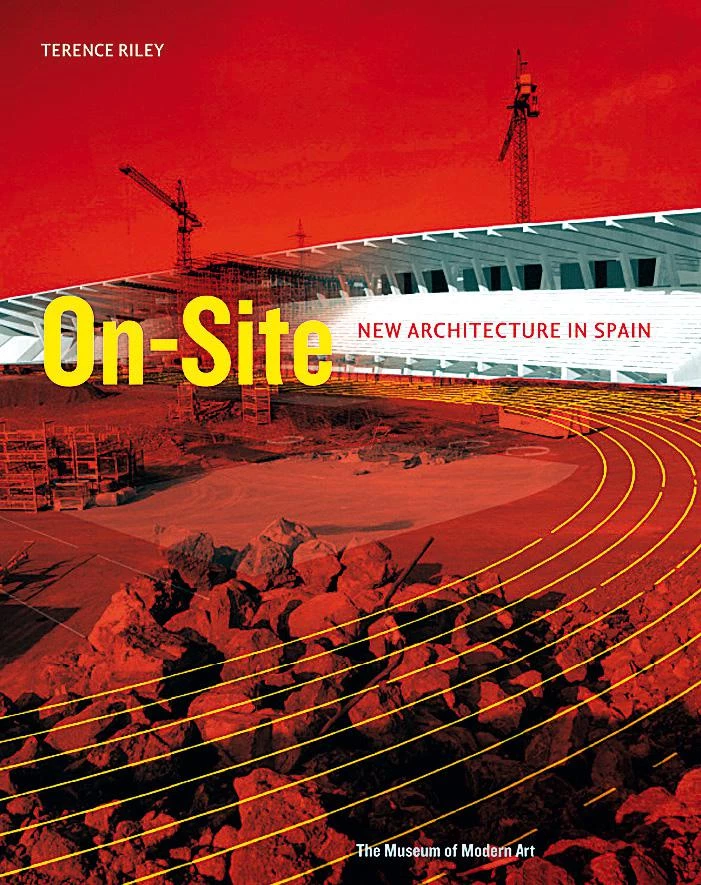

Spain builds; but not Spanish architecture. Unlike the mythical Brazil Builds, that in 1943 presented at the Museum of Modern Art the tropical and sensual reinterpretation of modernity as an unmistakably Brazilian architecture, On-Site places the last projects and works in Spain in the world's spotlight, giving our country the rare honor of a monographic exhibition, but without demanding for itself any attribute other than excellence. Variety and openness are in effect the two characteristics of the exhibition: variety of languages as a result of the diversity of authors, without noticing common features that define generational groups or regional schools; and openness, because almost one third of the authors exhibited are foreigners, underscoring both the country’s desire to open up to the talent from abroad and the interest of the international stars in Spain.

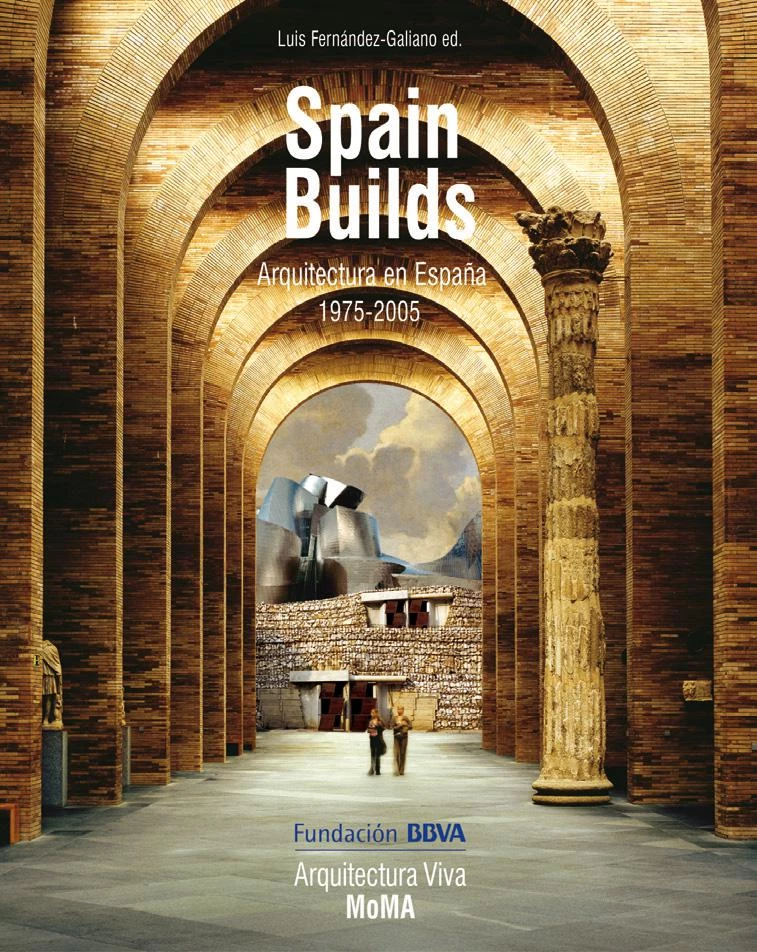

On-Site, the catalogue of the show, was joined by Spain Builds, a historical survey of architecture in the country since 1975.

The mere enumeration of these is already impressive: Chipperfield, Eisenman, Gehry, Koolhaas, Hadid, Herzog & de Meuron, Ito, Mayer, Mayne, MVRDV, Nouvel, Rogers, Perrault, Sejima & Nishizawa, Siza. Few places in the planet can boast about having a similar concentration of architectural stars, an even more noticeable circumstance if one recalls that other big firms with important projects in Spain are not in the exhibition. But this arrival of international offices arises within the context of a high-quality local production, that can undoubtedly be favorably compared with the imported architectures, and that has a growing presence in the global scene.

The only Spanish Pritzker, Rafael Moneo, was present in the exhibition with his Murcia Town Hall extension, a building that sets up a dialogue with its context through the geometric abstraction of the stone facade.

Though the list of Spanish studios present at MoMA is too long for a detailed commentary, it is worth mentioning that only five of them – Ábalos & Herreros, Arroyo, Mansilla & Tuñón, Mangado and EMBT – appear both in the group of projects and in that of works, within a list that covers the peninsula and the Balearic and Canary Islands. All the seventeen regions – if we were to consider La Rioja represented by Gehry’s wineries in Elciego – are in New York with at least one project, a geographic equanimity that originates in the determination and the countless trips around Spain of the show’s curator, whom with this exhibition rounds off thirteen years in charge of the museum’s Department of Architecture and Design.

Among the architects with two works in the show were Mangado (left, Baluarte in Pamplona), Ábalos & Herreros (below, Woermann tower in Santa Cruz) and Mansilla & Tuñón(bottom, León’s MUSAC).

It is perhaps significant that – instead of a thesis exhibit – Terence Riley has decided to say farewell with an exhibition of this nature, necessarily diverse and disperse, but perhaps the disoriented fragmentation of the times is better expressed through a heteroclite collection of excellent projects. In any case, the curator wished to highlight the historical roots of this spectacular flowering of architectures in Spain by promoting a complementary book, Spain Builds, which illustrates the origins of the current panorama in the decades of democracy, which chose to represent itself through modern architecture, and even in the long years of Franco’s regime, during which the masters of the last generations – Coderch, De la Sota, Oíza or Fisac – developed most of their career.

The list of authors with double representation in the New York Spanish exhibition also included Eduardo Arroyo (below, Baracaldo Stadium) and Miralles & Tagliabue (bottom, Santa Caterina Market in Barcelona).

This essential continuity – together with the rigorous polytechnical education offered in universities, the power of the architectural associations, the ‘colegios’, and the survival of trades – was at the base of the works that captivated the world in the eighties, with the coming-out party of 1992. However, all these sources of architectural quality are in crisis today, and we cannot rule out that the deterioration experienced by urbanism and landscape design may extend to an architecture increasingly dependent on the real-estate boom and the conspicuous generosity of the public sector. Meanwhile, we can only congratulate ourselves on having architecture as our banner and as our most admired cultural expression; and we cannot but thank the MoMA – 25 years after the return of the Guernica – for this new gesture of friendship.