Roses in Winter

A congress in Pamplona and an exhibition in New York reflect the rise of social commitment in architecture, determined to offer more for less.

The classics advise not to wish for roses in winter. Our world, however, is built with desires out of season, and those undue appetites govern markets and lives. The temperature of consumption controls financial fluxes and the libidinal economy, in a network of meshes that oppresses or holds the obese bodies of coun-tries and people. We try to understand what is going on, but do not realize that what happens is that too many things happen, weighing heav-ily upon us. This burden of unnecessary objects and arbitrary needs gravitates over a material and social fabric that loses shape underneath its weight, creating a debt of desire that is as in-candescent and toxic as the monetary debt that keeps us all expectant, fearing market shocks that can undermine the stability of our eco-nomic ecosystems. The current crisis seemed to be a perfect storm able to clean the air, but its wild violence is rather creating a jungle-like disorder, and perhaps we will only be able to ride it dropping ballast overboard.

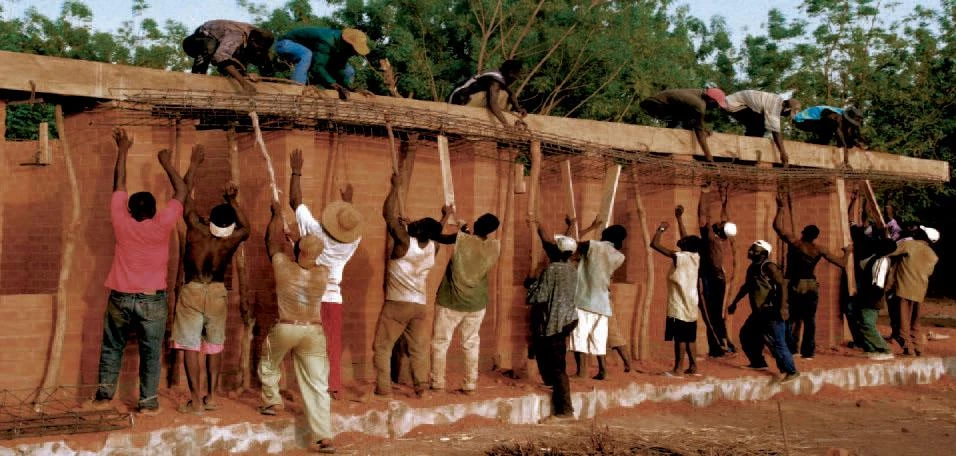

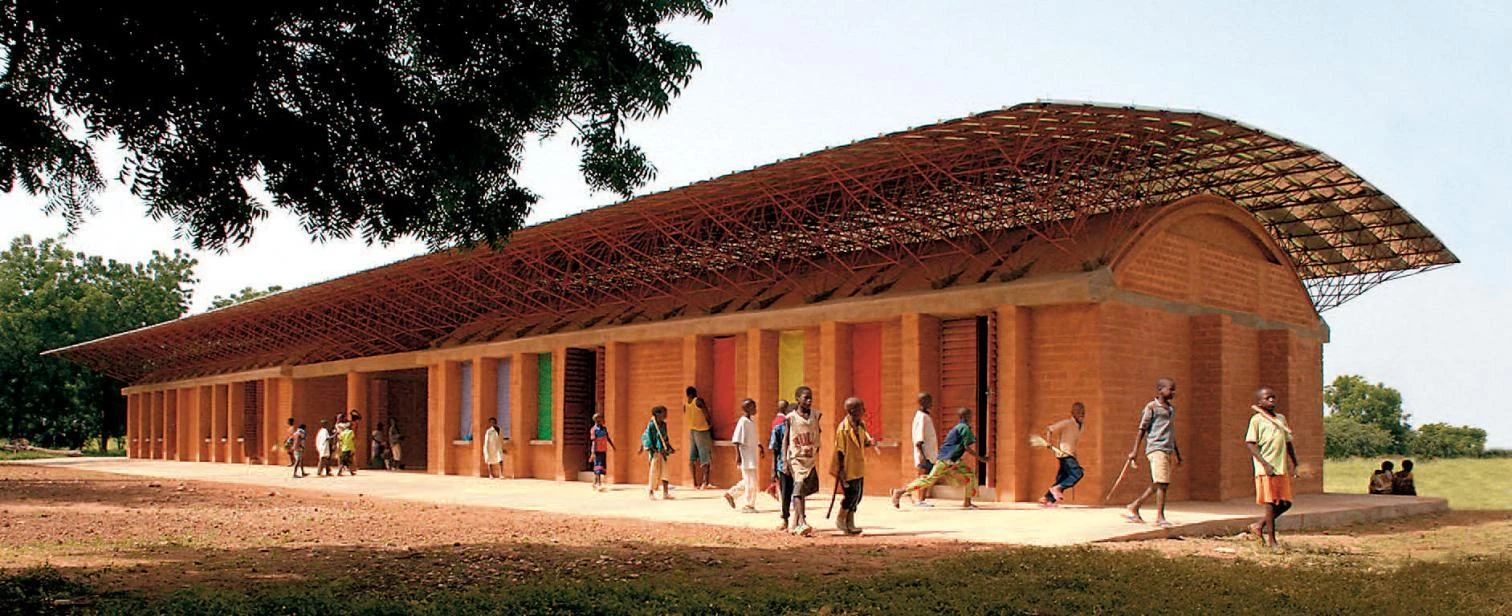

The elementary schools by Diébédo Francis Kéré in Burkina Faso use local materials and village labor, combined with technical skill, to build in tune with the climate, the economy and the culture of the place.

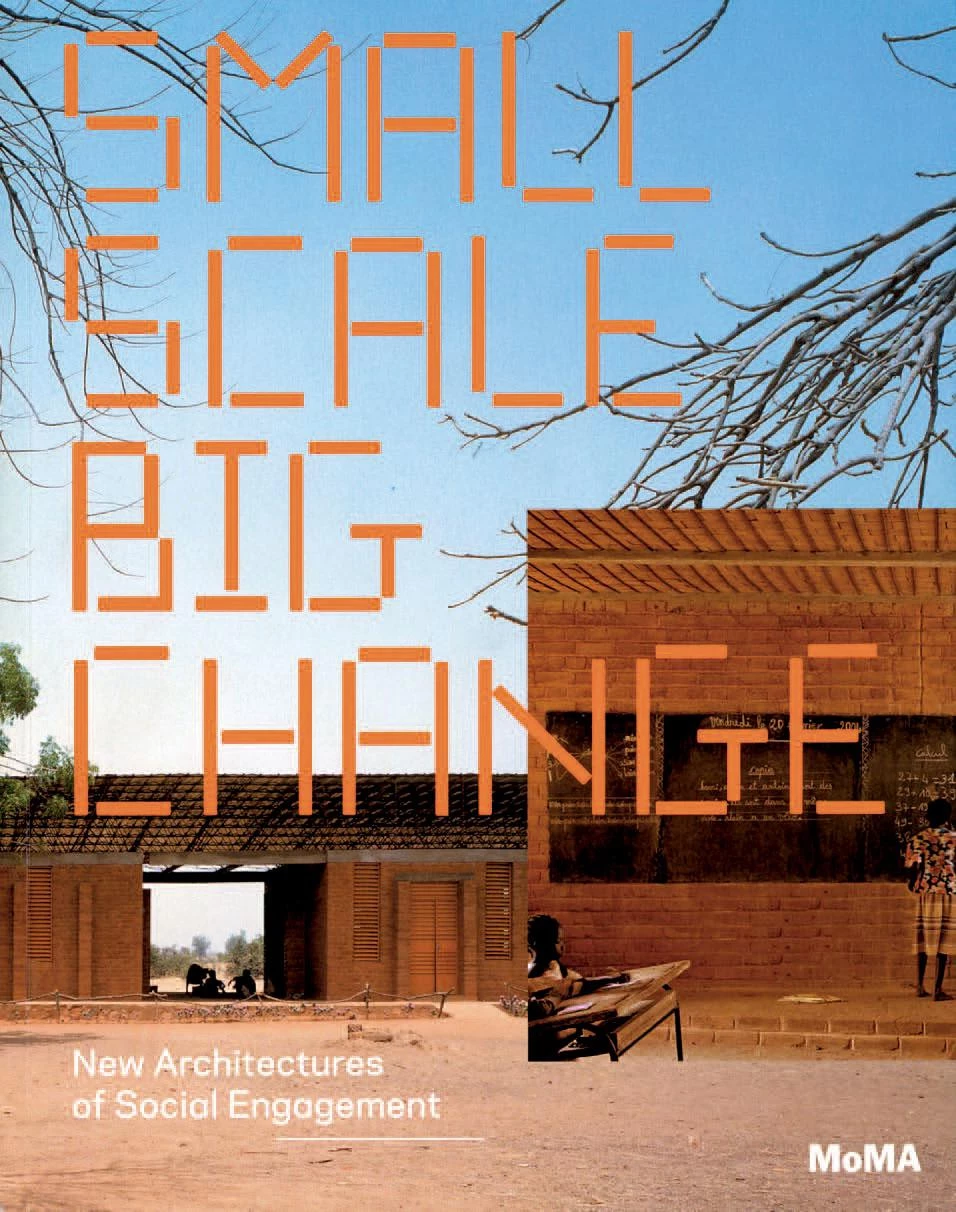

In the field of architecture, where excesses have been so notorious of late, two recent events may herald a change of attitude: an internation-al congress held in Pamplona in June under the motto ‘more for less’ and an exhibition shown in New York since October with the title ‘Small Scale, Big Change’. The congress, organized by the Fundación Arquitectura y Sociedad, gathered fifteen figures from the five continents who offered a choral portrait of the state of an art in mutation, where the need to offer more efficiency, more commodity and more pleasure with less material, less energy and less money is a welcome return to timeless logics. The exhi-bition, held at the Museum of Modern Art with an ambitious layout that combined large models, original documents and videos, grouped eleven projects of both Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe – from a school in Bangladesh or a museum of the apartheid in South Africa to the transformation of a social housing block in Paris or the regeneration of a favela in Rio de Janeiro – which were described as the new architectures of social commitment, because by addressing the needs of underprivileged environments they hope to reestablish the old, resilient ties between architecture and societ.

As much the book of the congress, which includes in-depth interviews of the protagonists, as the exhibition catalogue, which features the projects in detail, define new roles for architects in these times: one of technical and economic responsibility, completely detached from self-indulgent narcissism; and one of social and civic service, shared with many other creative professions. That sense of responsibility and that sense of service often express themselves through the relinquishment of all frills, through the effort to separate the substantial from the superfluous, and through the determination to reach those goals using limited means. It is an architecture that tries to reconcile the aesthetic excellence of its objects with the ethical excellence of its processes, that defines the needs of its users as the center of its activity, and that in the end places itself at the service of life.

Las viviendas sociales de Alejandro Aravena y Elemental en Chile se construyen con volúmenes escuetos y desnudos que los habitantes completan y personalizan, según sus recursos y necesidades, a lo largo del tiempo.

Three architects from three continents were present in both events, and their profiles may serve as examples of this emerging field. The Chilean Alejandro Aravena and his group Elemental have promoted the construction of housing for poor communities – often living in slums or favelas –, with high-density, low-rise developments that the users themselves complete in dialogue with the architects but using their own means; an exemplary exercise of joint responsibility that relieves the financial burden of the State and the owners while creating efficient and sustainable neighborhoods.

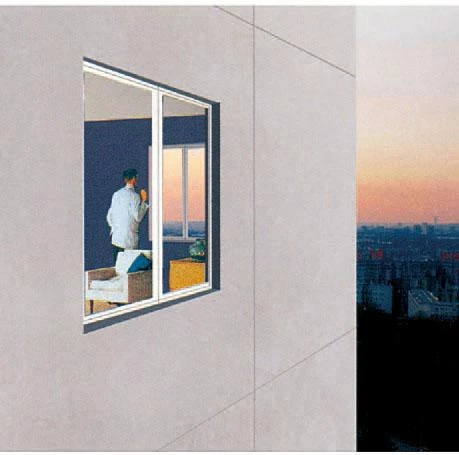

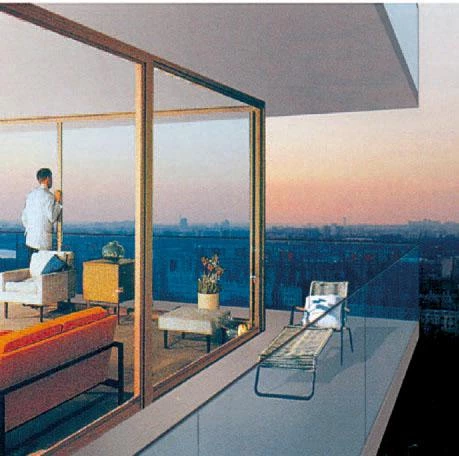

For their part, the French Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal have approached social housing with the regeneration of the anonymous blocks and towers of the 1960s that rise in the peripheries of all European cities, whose demolition (and the huge waste this entails) the architects avoid with prefab modules super-posed to the existing facades to endow the buildings with the space, comfort and transparency they need, refurbishing obsolete structures with limited means and broad intelligence.

Lastly, Diébédo Francis Kéré has built schools in his native Burkina Faso combining vernacular materials and the work of locals with the technical skill acquired during his training in Berlin, thus giving his native village the most important tool for development: func-tional, cool and well-lit classrooms completed with scarce funds and raised with adobe blocks and lightweight roofs, whose moving beauty lies in their laconic austerity.

The residential works by Lacaton & Vassal use engineering structures or agricultural greenhouses to refurbish the existing or to build new, luminous houses with more floor area and less cost than the conventional ones.

Though many of these commendable experi-ences occur in contexts of scarcity, the lessons they offer in the use of resources have a general value that go beyond this circumstance. More prosperous places could draw inspiration from these attitudes, to responsibly face not only the current economic difficulties, but also the more far-reaching ecological problems, and above all the cultural crisis caused by the excess of goods and stimuli, which numbs our sensibility and devalue the meaning of objects, spaces or affections: giving up the redundant messages and unnecessary devices that besiege us can be a source of intellectual and emotional richness, because doing without the accessory allows us to concentrate on what really matters.

All in all, these architectures of need are also architectures of desire, however much this desire is focussed on the exact dignity of the everyday rather than on the extravagant offers of the exceptional, whose quantitative result has been a real estate bubble that has devastated our landscapes and our finances, and whose qualitative expression has been a crop of iconic works that, with great economic cost, have promoted originality as the only attribute that gives visibility in our media culture, replacing the silent elegance of bareness and subordination to the essential demands of society.

Thirty years ago I telegraphically summa-rized in a newspaper article (‘Arquitectura de papel, papel de la arquitectura’) the state of architecture at the time: “In the last two decades we have seen the technical emphasis of the early sixties followed by the sociological passion of the seventies, and the latter in its turn replaced by the artistic fervor that appears as the most characteristic feature at the beginning of the eighties”. A long time has gone by, and that artistic fervor sparked a bonfire of vanities that, once the flames are put out, only leaves an aftertaste of ash. But in this wasteland of ours, covered with rubble and slag after the volcanic eruption of feigned prosperity, a new generation has appeared:one that strives to offer more for less, changing the world and changing us all with its aesthetic of the necessary and its determination not to wish for roses in winter.