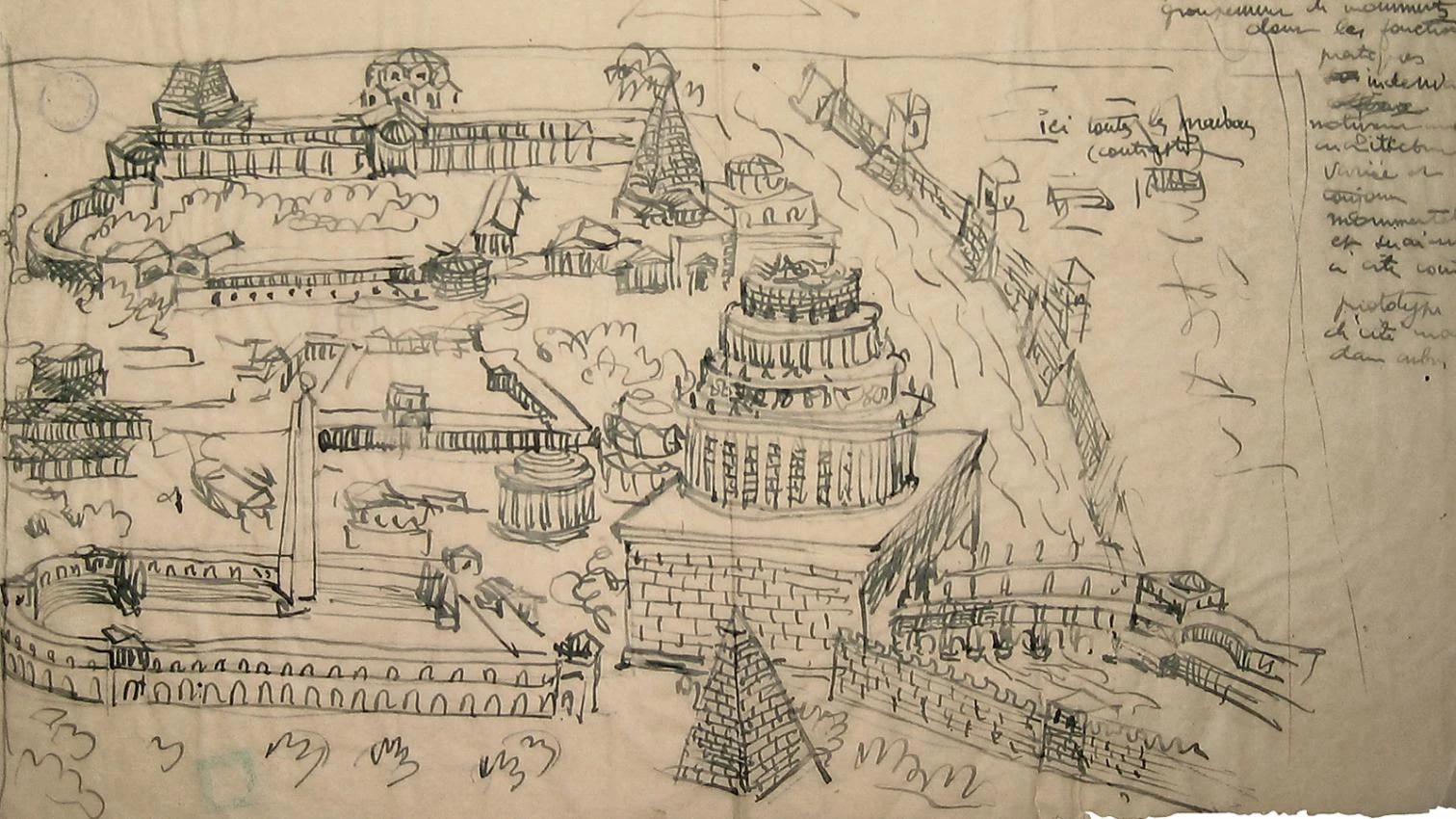

In Principes de géographie humaine, published in 1921, geographer Paul Vidal de la Blache evoked “[the] arches and the domes, all of this marvelous flowering which has alternately expressed Egyptian and Hellenistic art, that of Rome, and that of Byzantium,” and added, “It is not only an art lesson that we seek in the monuments or ruins which remain standing, but also an example of what can survive of human enterprise.” This characterization anticipated by only a few months Le Corbusier’s own “Leçon de Rome,” first published in L’Esprit nouveau in 1922 and then in Vers une architecture (1923), his most famous manifesto. In the latter he also presented “three reminders” to architects and called on his readers to open their “eyes that do not see” to three types of mechanical objects. But he would formulate only one lesson – that of Rome, whose features appear in no fewer than 21 of the book’s 218 illustrations.

Jeanneret did not visit the Italian capital during his travels in 1907. It was only in October 1911, on his way home from an extended trip through the Balkans, Turkey, and Greece, that he finally landed in the city that originally was to have been the first stop on his itinerary. Prior to this, he had explored Rome in the pages of Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerichen Grundsätzen (City Planning According to Artistic Principles) (1889), by Camillo Sitte, and in Platz und Monument (Square and monument) (1908), by Albert Erich Brinckmann. In these two books, which he consulted in Munich’s libraries, he discovered the urban spaces of ancient Rome as well as the squares of the modern city. The only explicit outcome of this reading was his recommendation, in the notes for his manuscript “La Construction des villes” (1910-15), to “take heed of the notion of the protection of buildings, of streets, of open places, of shadows of the city (Rome: the monument to Vittorio-Emanuele, the quarter close to St Peter’s, the banks of the Tiber, and the Castel Sant’Angelo).”...