In the Cause of Landscape

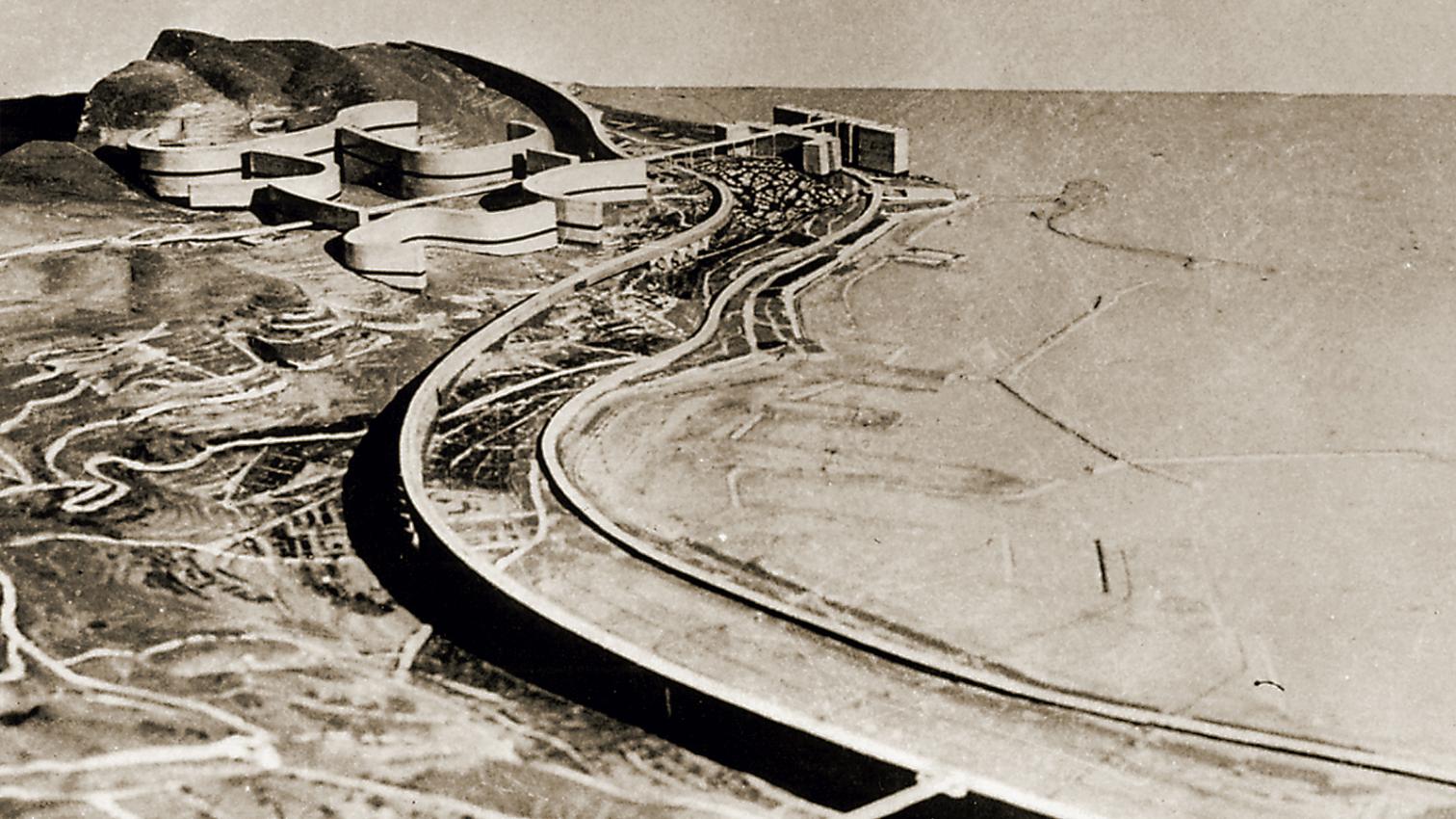

If there is a blind spot in the astonishingly vast literature dedicated to Le Corbusier, it is certainly his relationship to landscape, which provided him with scenes to observe, stimulation for invention, horizons against which to set his projects, and also a fertile field for metaphors.

Even though few architects have been as extensively studied – in all aspects of his production, from buildings and city plans to paintings, drawings, and publications –, and even if his abundant correspondence has revealed the complexity of his thought and the contradictions between his public persona and inner reflections, stereotypes about him persist, often the result of his own rhetoric.

None of the large exhibitions of Le Corbusier’s work over the last thirty years, from those organized at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Hayward Gallery for the centennial of his birth, in 1987, to ‘The Art of Architecture’, a traveling exhibition that began its journey in 2007, have meaningfully addressed the issue of landscape. Certain isolated authors have analysed its role, often in relation to specific projects, such as Caroline Constant on Chandigarh and Bruno Reichlin (the first scholar to consider specific buildings by Le Corbusier as machine. for viewing the landscape) on the Villa Le Lac, in Corseaux, and sometimes in a broader context, such as Beatriz Colomina; there is also Dorothée Imbert, who has discussed the gardens of the houses of the 1920s and ’30s. With the exception of these interpretations – along with an issue of Casabella on Le Corbusier’s strategies of observation, a symposium on his relationship to nature, organized by the Fondation Le Corbusier in 1991, and a provocative issue of Massilia, the journal of Corbusian studies, devoted to landscape in 2004 – this dimension of his work has remained largely unexamined.

The term ‘landscape,’ in use in the Anglophone world since the end of the sixteenth century, denotes both the physical and visible form of a specific outdoor space and its graphic, pictorial, or photographic representation; strictly rural originally, it is understood today to be nonspecific. In his Court traité du paysage of 1997, philosopher Alain Roger underlined the intimate connection between the two meanings, demonstrating that landscape resulted from the cultural construct of artialisation. Using this term, Alain Roger argued that landscape was impossible without representation. The fertility of the notion in Le Corbusier’s work stems from this ambiguity, in which many semantic meanings overlap...