The most radical modernity aspired not so much to revamp architecture as to destroy it. The project was at first undertaken by futurists obsessed with turning buildings into atmospheres of air and energy. Having failed, this utopia of dissolution remained in the limbo of manifestos until it revived in the 1960s and 1970s through Banham, Price, Hollein, and Archigram and their coloristic, hippie, and radical visions which had actually had an immediate and quite different precedent: the family of rare birds who, technophile and no less radical, fascinated by the culture of communications, surrendered to the dream of post-architecture. A family led by a holy trinity of modern heterodoxy: Constant Niewenhuys, Richard Buckminster Fuller, and Konrad Wachsmann.

The critic Mark Wigley has devoted a good part of his prolific career to salvaging the life and work of these three leaders of post-architectural language. First he wrote Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire (1998). Next came Buckminster Fuller Inc.: Architecture in the Age of Radio (2015). And now comes his equally excellent Konrad Wachsmann’s Television: Post-architectural Transmissions (2020), which with a micro but ambitious format looks at the German architect’s trajectory in the light of his powerful personality, his works, and above all his influence on young people, who saw him as a spokesperson for an architecture still to come: an architecture built with bolts but also with electromagnetic waves, and in which the urge for authorship credit would dissolve – that great technocratic dream – in the arena of collective needs.

To map the complex Wachsmann world, Wigley resorts to TV both literally and metaphorically. Literally to the extent that Wachsmann was quick to detect the role that communication by waves played in contemporary societies, and postulated an architecture in accord with it: an architecture for the fluctuation and constant exchange of opinion, an architecture obsolescent and de-materialized, an anti-architecture. And metaphorical to the degree that Wachsmann’s works, writings, and person can be understood as a screenful of ever-changing data that has been received quite disparately.

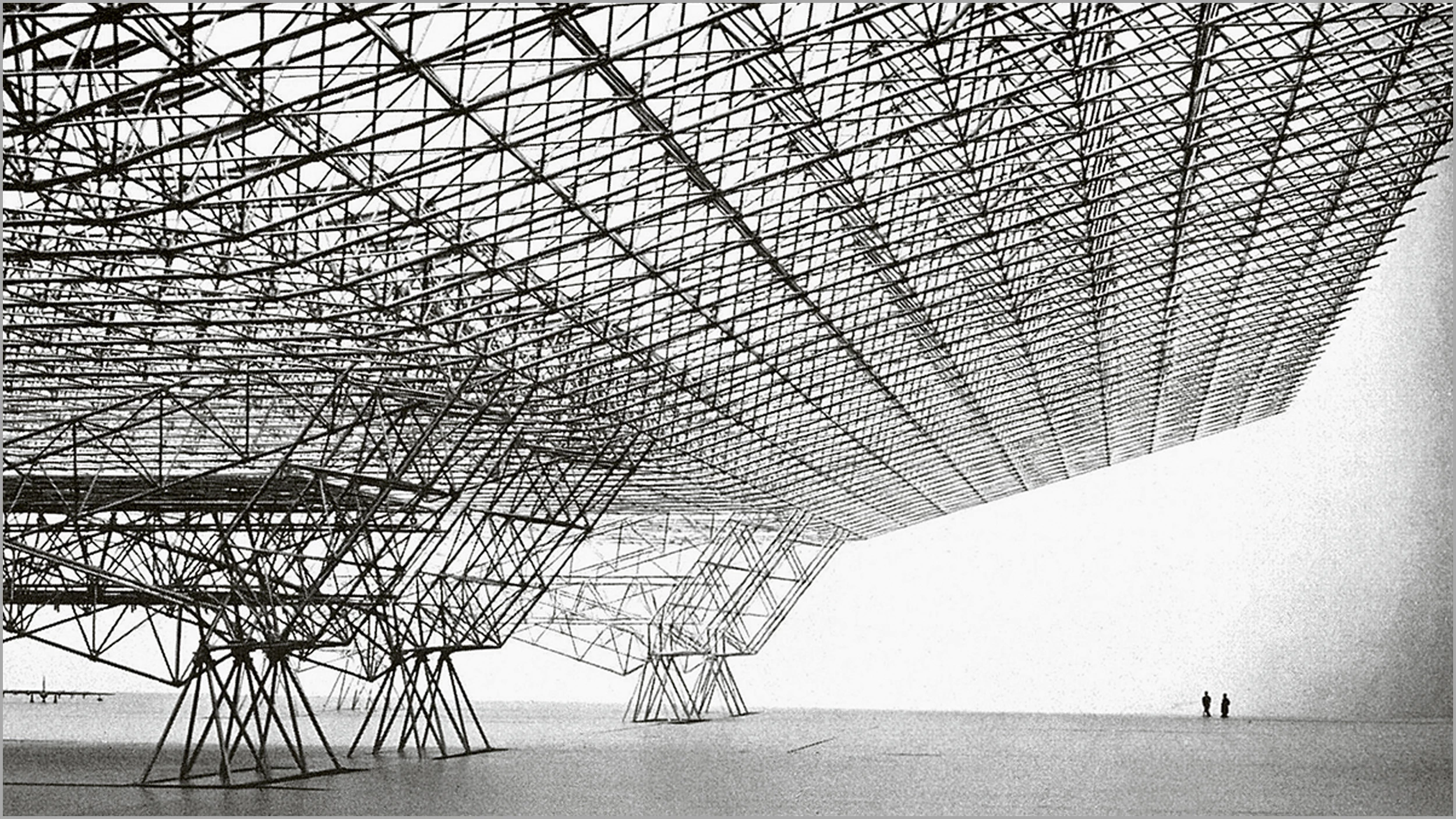

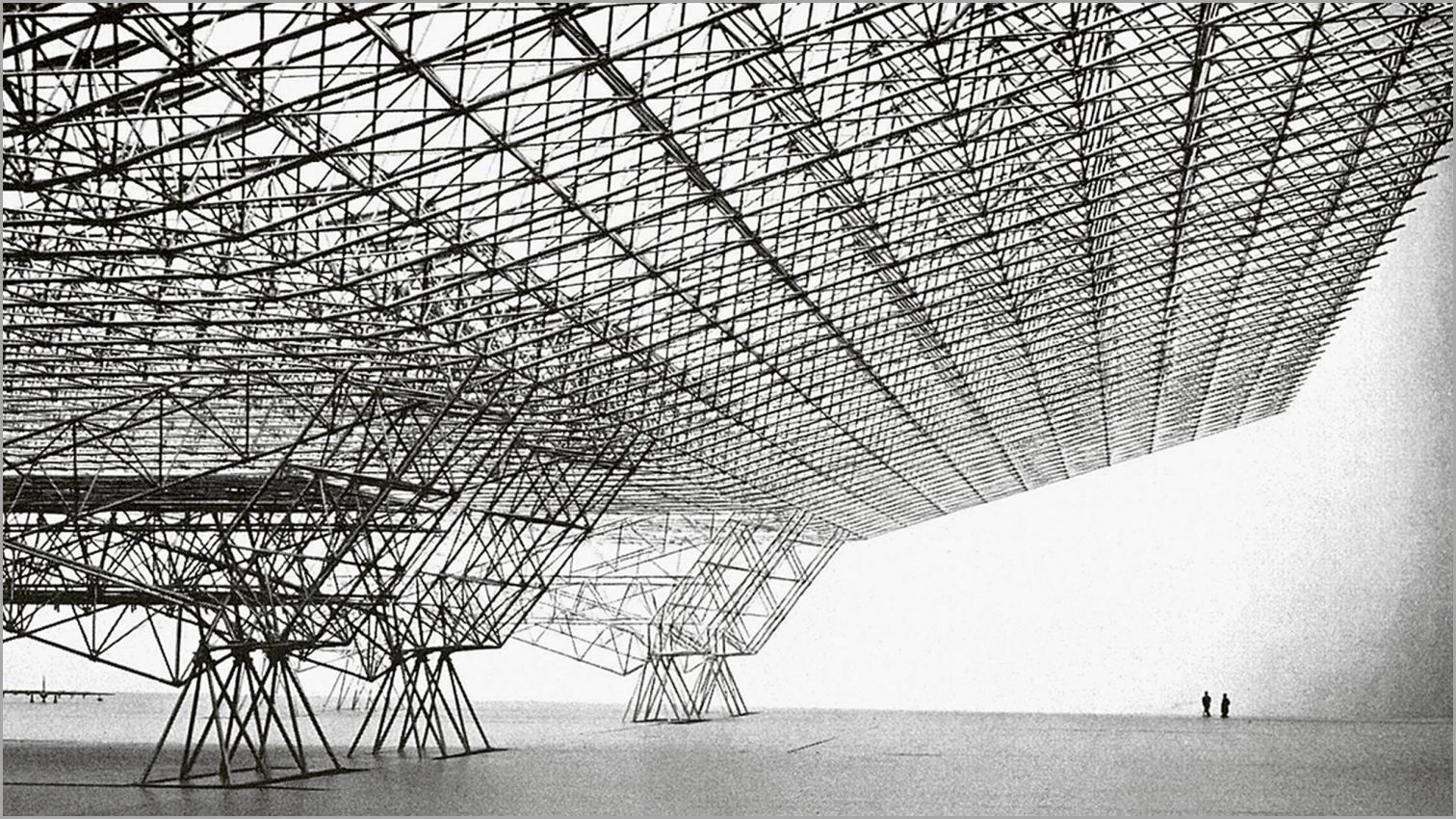

With this double television valence, the author crafts a narrative that is also two-way. On the one hand, with abundant data he presents Wachsmann as Paxton’s heir and as a master of prefab construction, paying equal attention to his studies with three-dimensional trusses – the Mobilar Structure, the Hangar Air Force – and his inquiries into cable structures, such as the California Civic Center. On the other hand, he traces the silhouette of Wachsmann the thinker and agitator through his manifestos, class lectures, and conferences: a Wachsmann in dialogue with a period in which the medium was becoming the message.

Thanks to this efficient mix of methodological approaches, not to mention his clear prose, Wigley brings Wachsmann back from the dead, although it is hard to determine if the German’s technocratic and social optimism, and his at once devastating and naive view of architecture, can really fit into times like ours, when communication media, inhabited by the digital Leviathan, are no longer instruments of emancipation but weapons of sheer dominion.