News from Córdoba

Koolhaas will build his first Spanish work in Córdoba, after winning over Cruz & Ortiz, Hadid, Ito and Moneo in the Congress Center competition.

Veni, vid, vici.The concise report of Caesar to the Senate serves well to describe the last visit to Spain of Rem Koolhaas: the rushed Rotterdam architect stopped in Córdoba just the necessary time to persuade a jury of the advantages of his project for the city, immediately resuming his journey in a rented jet, without even using the 25 meter pool that he had previously requested for his swimming exercises. Surly and impatient as some movie or rock stars, Koolhaas is also one of the most erosive talents of contemporary architecture, a strategist of urban form that conceals his refined pupil behind the solid graphic reasoning of the economy and the program. These rough modern virtues, more than the elegance of the line or the subtlety of the volume, earned him the internation-al competition for the Córdoba Congress Center, where he was measured against the laconic prag-matism of Cruz & Ortiz, the restless expressionism of Zaha Hadid, the atmospheric lyricism of Toyo Ito and the formal imagination of Rafael Moneo.

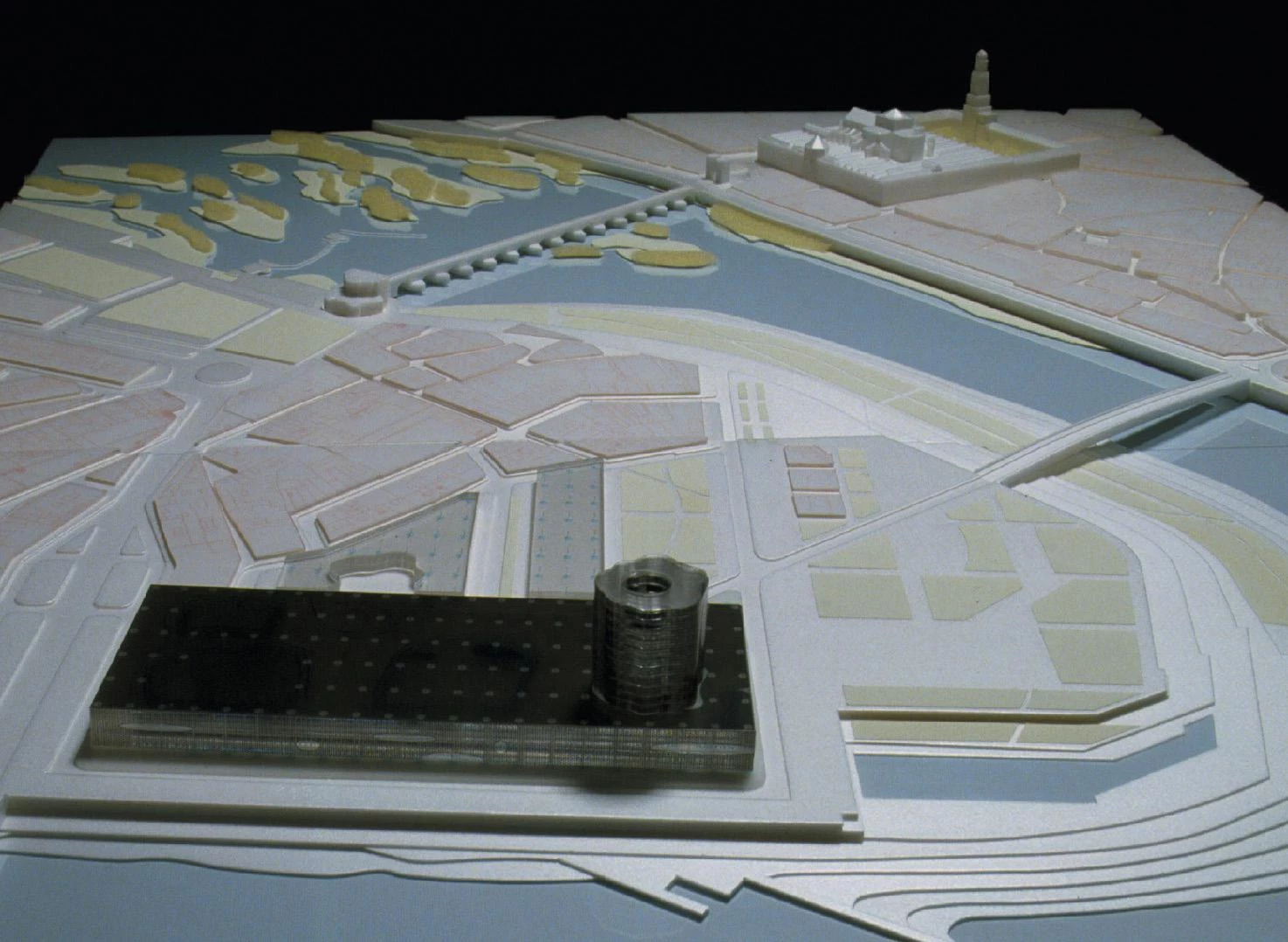

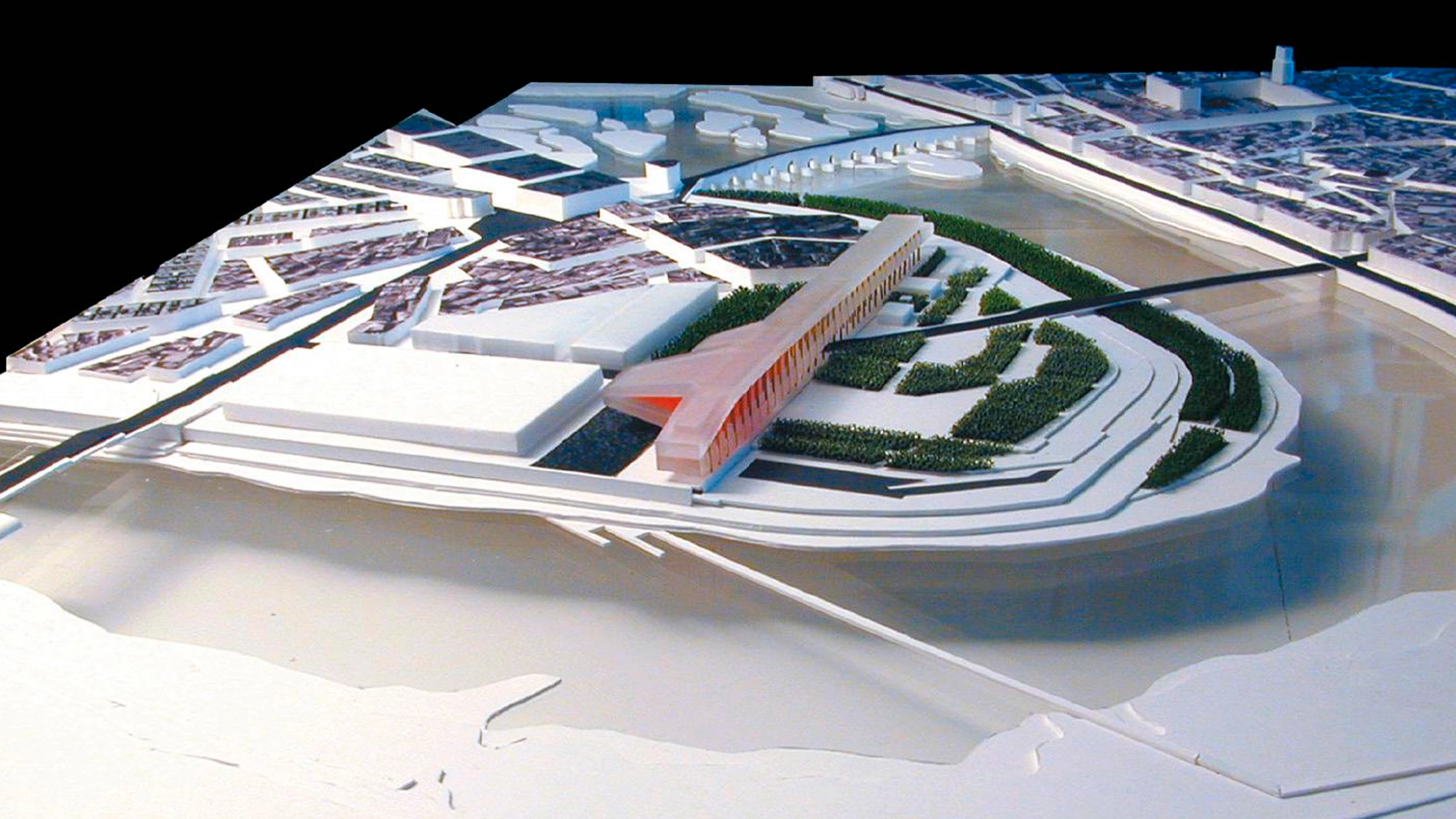

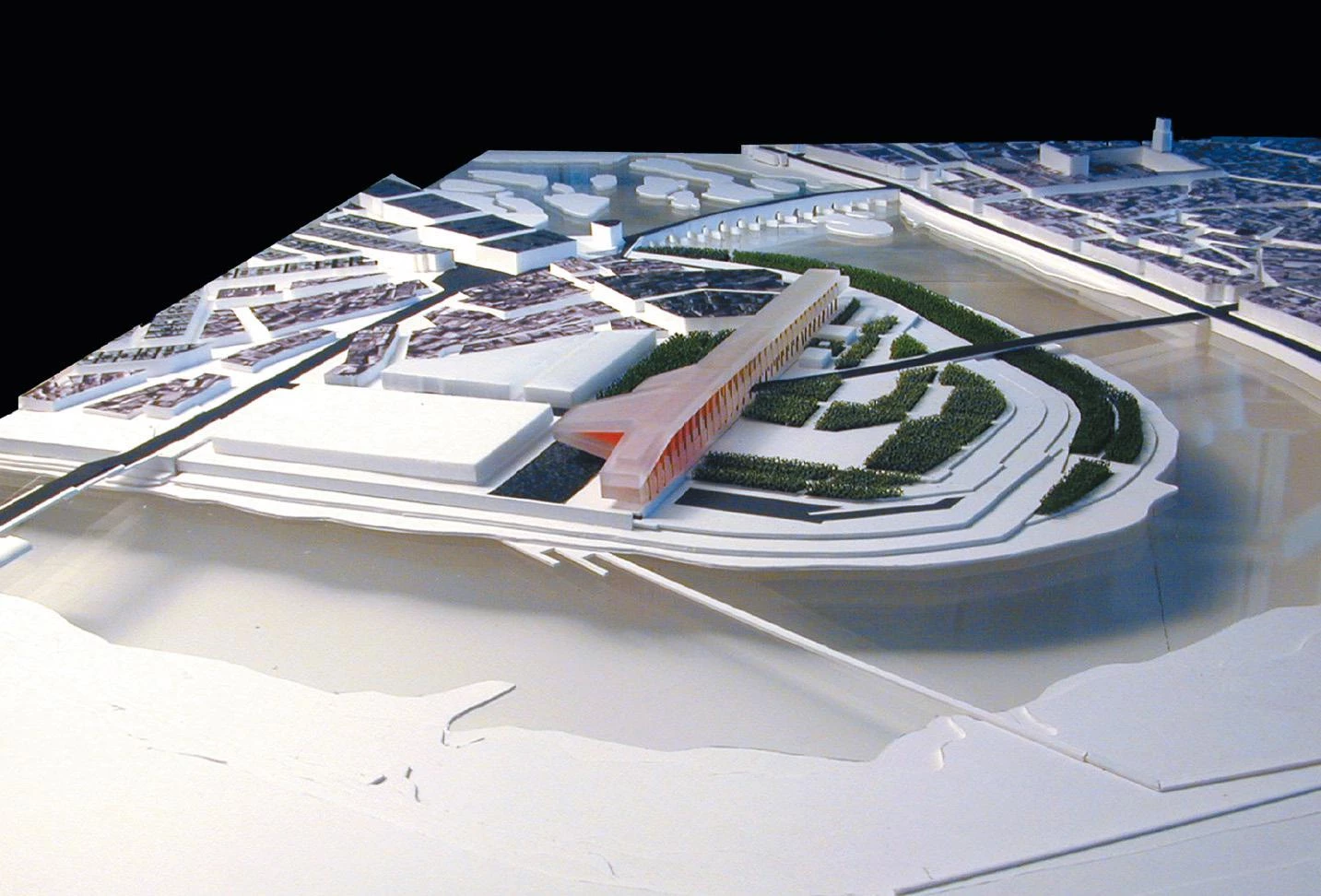

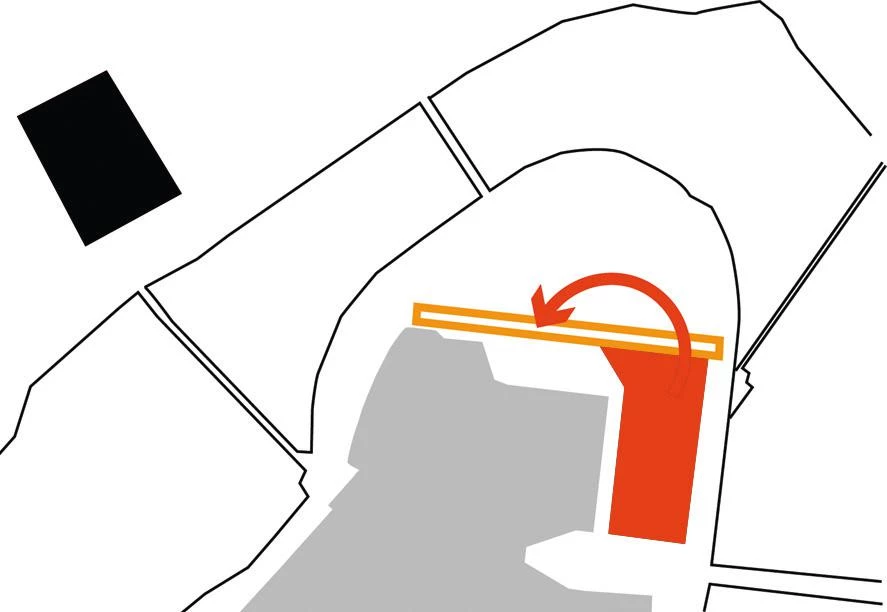

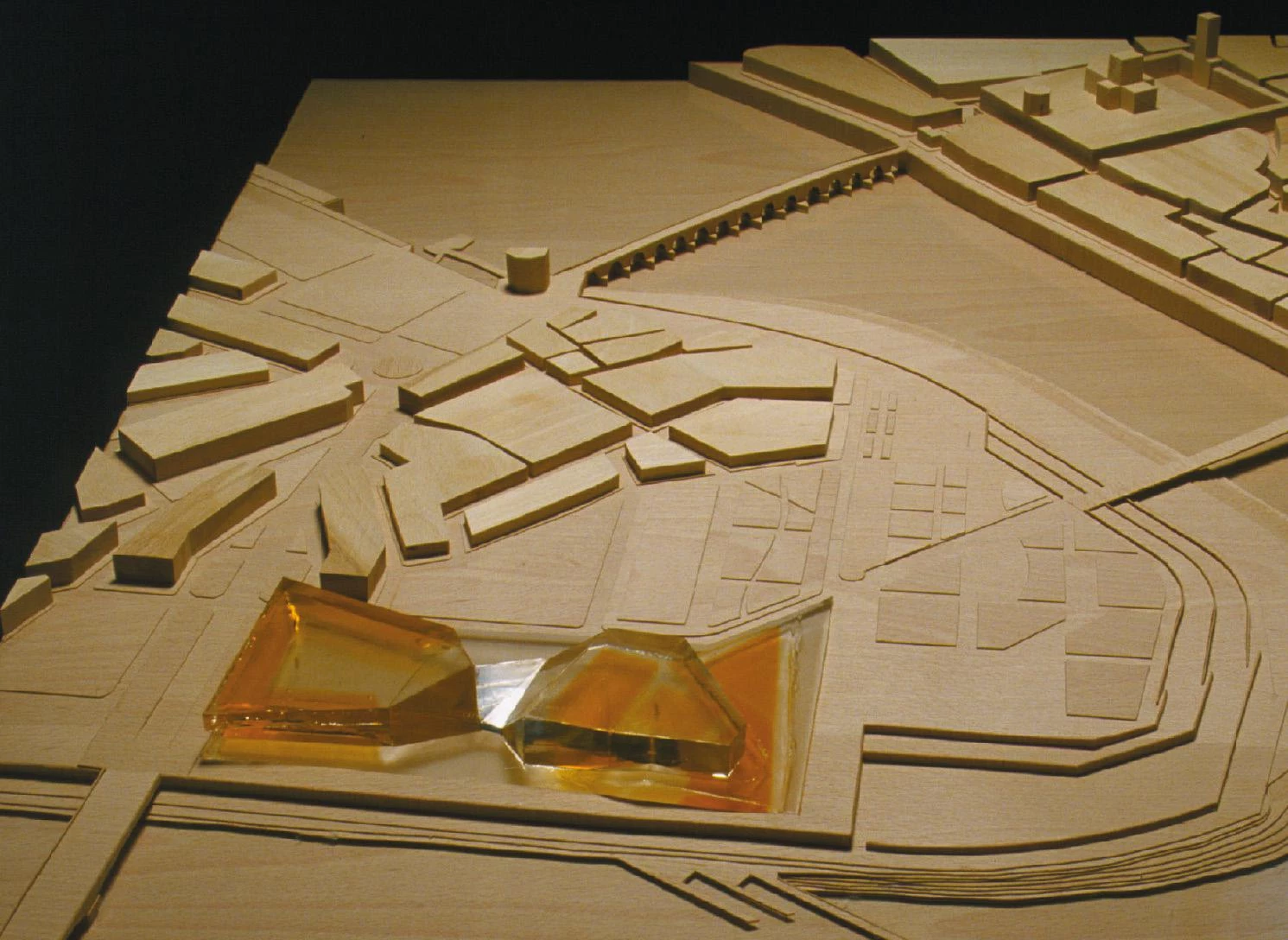

On a plot on the bank of the River Guadalquivir, facing the historic city and the Mosque, the Córdoba City Council invited the five participating teams of architects to design a development comprising a congress center, a hotel and a visitors’ center, with the double purpose of improving its touristic capacity and to revitalize a previously floodable area that today is underutilized in spite of its proximity to the historic center. The site chosen was a rectan-gle of 22.000 square meters, leaning on the defensive wall of the river, between the new Arenal bridge and the Miraflores park, now under construction; a plot as large as the Mosque itself, but unfortunately deprived of good views onto the monumental core of the city. Koolhaas faced this situation with the brilliant and risky decision to propose a building outside the competition area, using instead a 360 meter long narrow band that extends from one end of the river bend to the opposite, raised over the future park on pilotis, and allowing to assign new uses to the original site, with the foreseeable finan-cial advantages this option entails..

Koolhaas won the competition challenging the bases: he situated his building outside the designated site, proposing a linear block on pilotis, with the different elements of the program following one another in sequence.

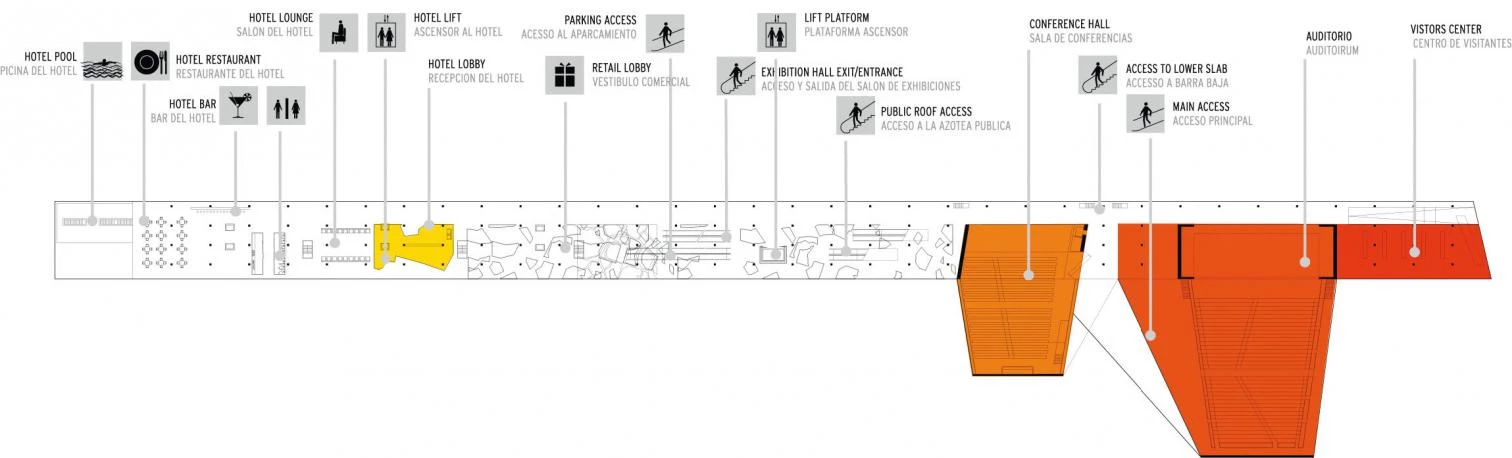

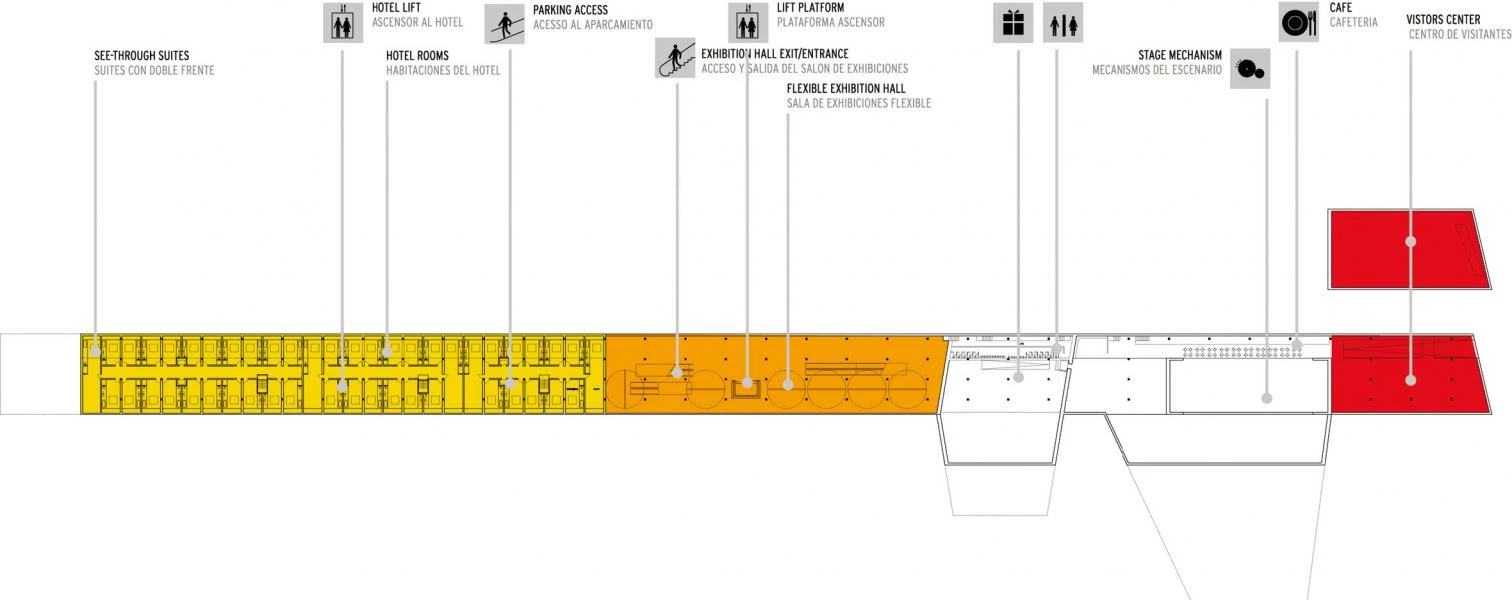

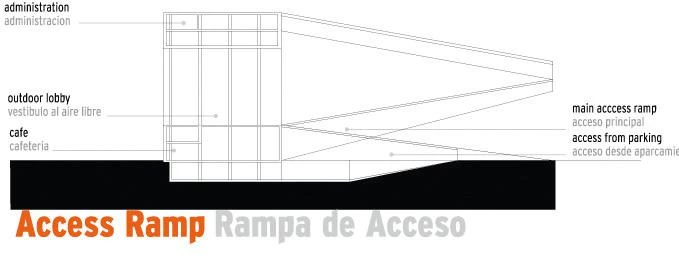

This disconcerting movement is carried out with an endless linear block where the elements of the program follow one another, from the visitors’center and the projecting wedges of the conference hall and the auditorium to the exhibition halls, the shopping area and the hotel that occupies the end closest to the Mosque, rounded off, incidentally, by the inevitable suspended swimming pool; this and other brand features of the studio – from the segregation of uses in juxtaposed functional bands to the open section, altering the horizontality of the slabs to adjust to the different needs of each segment – com-pose an object of impeccable presence that serves as a landmark meeting point for visitors and Cor-dovans, channelling the flow of people through a raised promenade that extends onto the roof, where the recreational uses are complemented with spectacular views over the historic center and the river. Corbusian in form and surreal in content, urbanistic in strategy and scupltural in tactic, this gradual and heterogeneous promenade is one of the most intelligent proposals of Koolhaas, and its iconic ar-gumentation – pictograms and graphics to visualize the quantitative information, in the tradition of Otto Neurath that goes on to Edward Tufte and Richard Saul Wurman – one of the most persuasive in the career of the Dutch writer and architect.

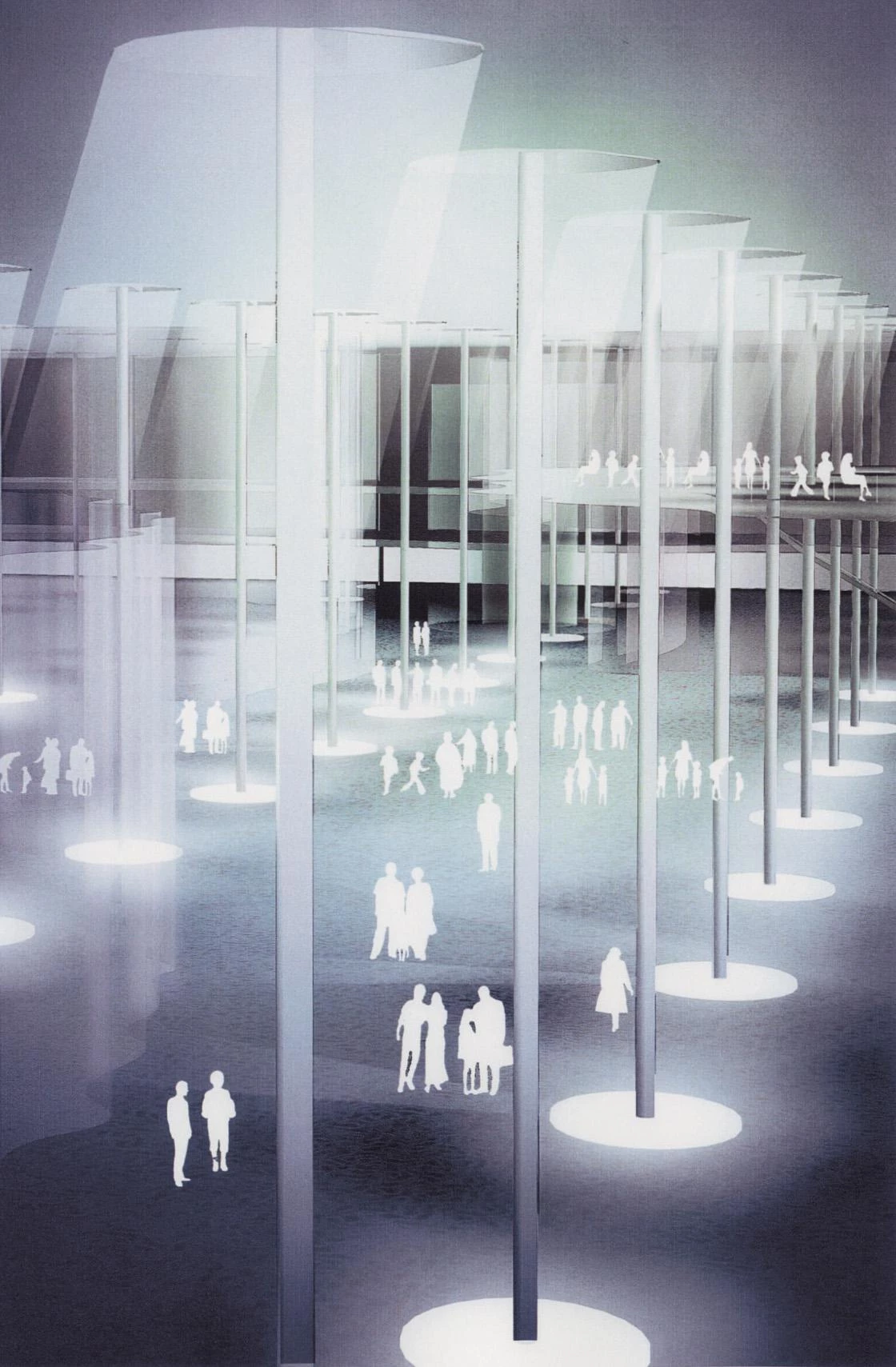

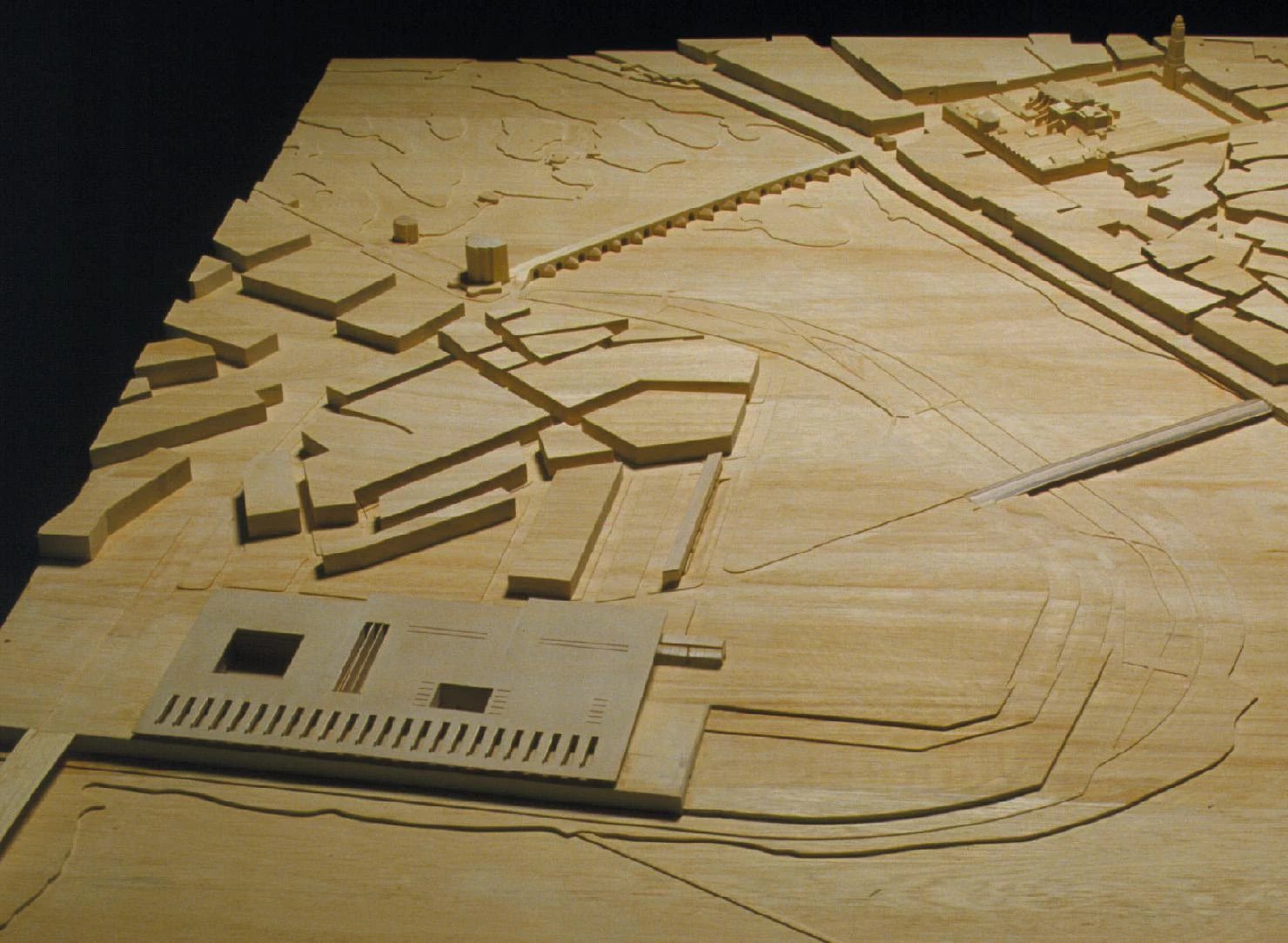

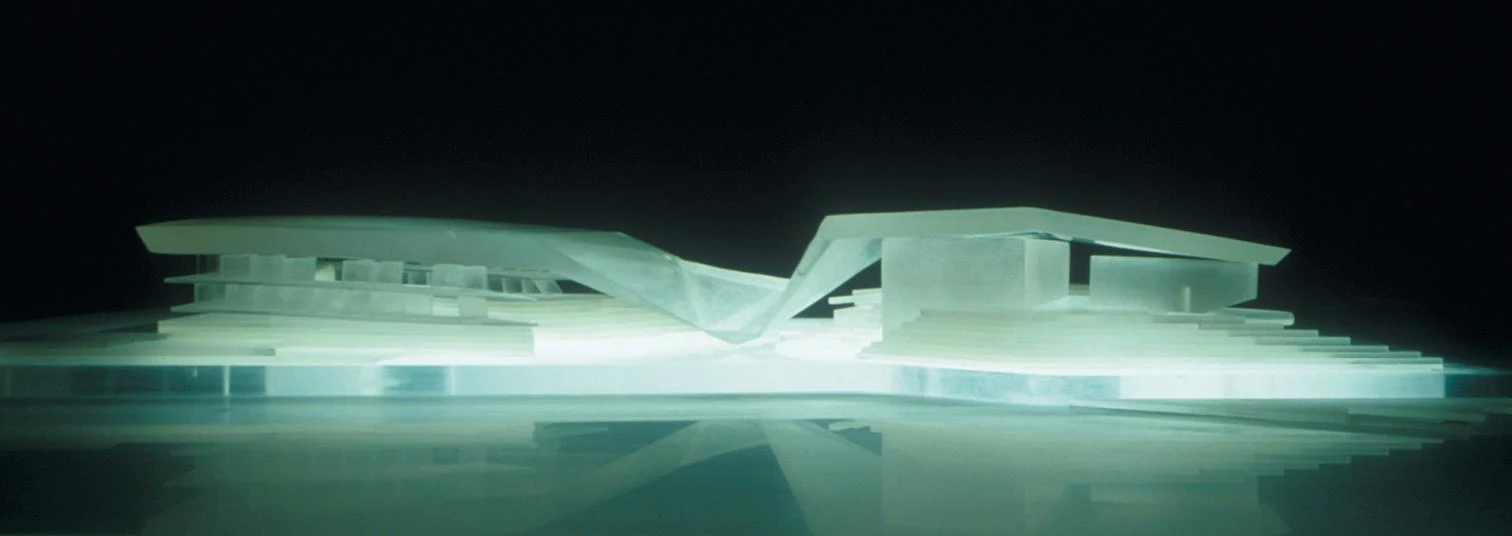

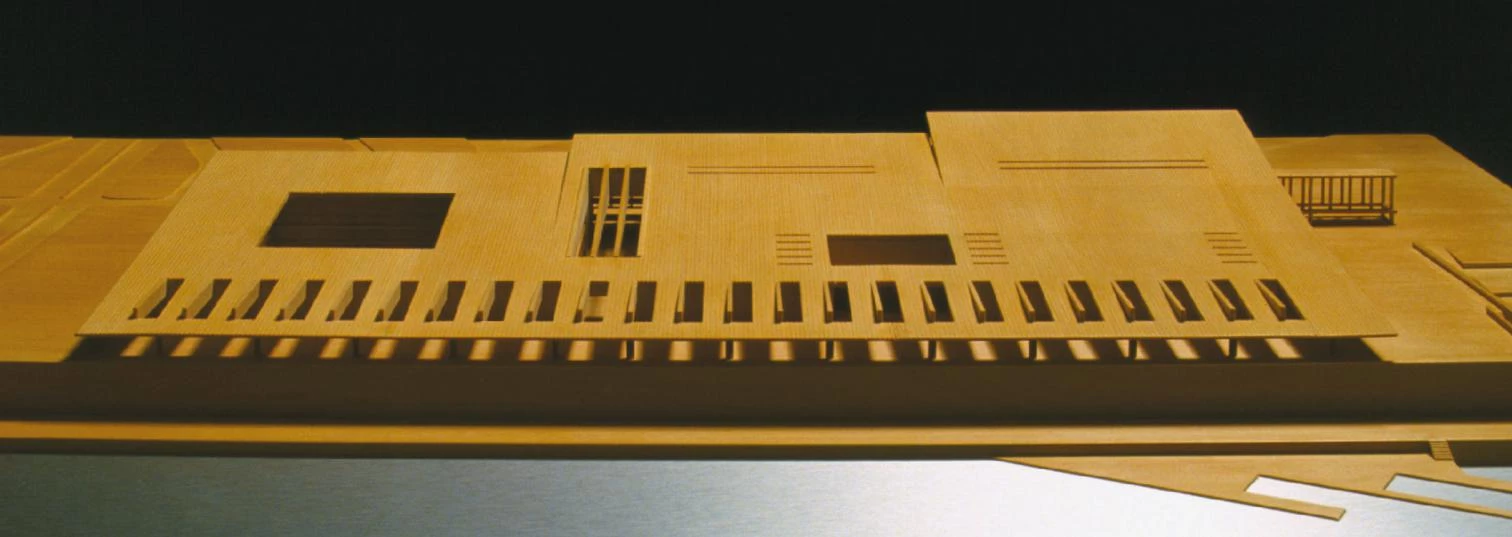

Koolhaas’s audacious approach, that ques-tioned the competition’s suppositions, also discon-certed the rest of the participants, that had orderly constrained themselves to the plot’s limits notwith-standing the objections of some of them. This was the case of the Sevillians Antonio Cruz y Antonio Ortiz, whose proposal – aware of the considerable distance between the predetermined site and the Mosque – brought the parking area for tourists close to the new Miraflores bridge, and even incorporat-ed the visitors' center into this same area to make the tourist promenades shorter and more enjoyable; but the main building was situated in the original site, effectively housing the congress halls and the hotel under a low-profile roof that sought to solve the program without a visual bearing on the city. On the other hand, the London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid preferred to express the dynamism of uses through a volume with diagonal penetrations, fin-ished off by one roof that folds in the center until it touches the ground, with as many functional incog-nitas as papyroflexial charm. Very different was the project of the Japanese Toyo Ito, a vast hypostyle hall that provides the replica to the Mosque with a labyrinth of penumbra, where steel, glass and water build with reflections a silent space interrupted by the waving volumes of the halls, the visitors’center and a hotel that pierces the flat roof to raise over it an extraordinary tower of rooms.

Cruz & Ortiz housed the program under a large eaning plane, moving the visitors’ center to the Miraflores bridge; and Zaha Hadid chose to break the volume diagonally, unifying the whole with a folding roof.

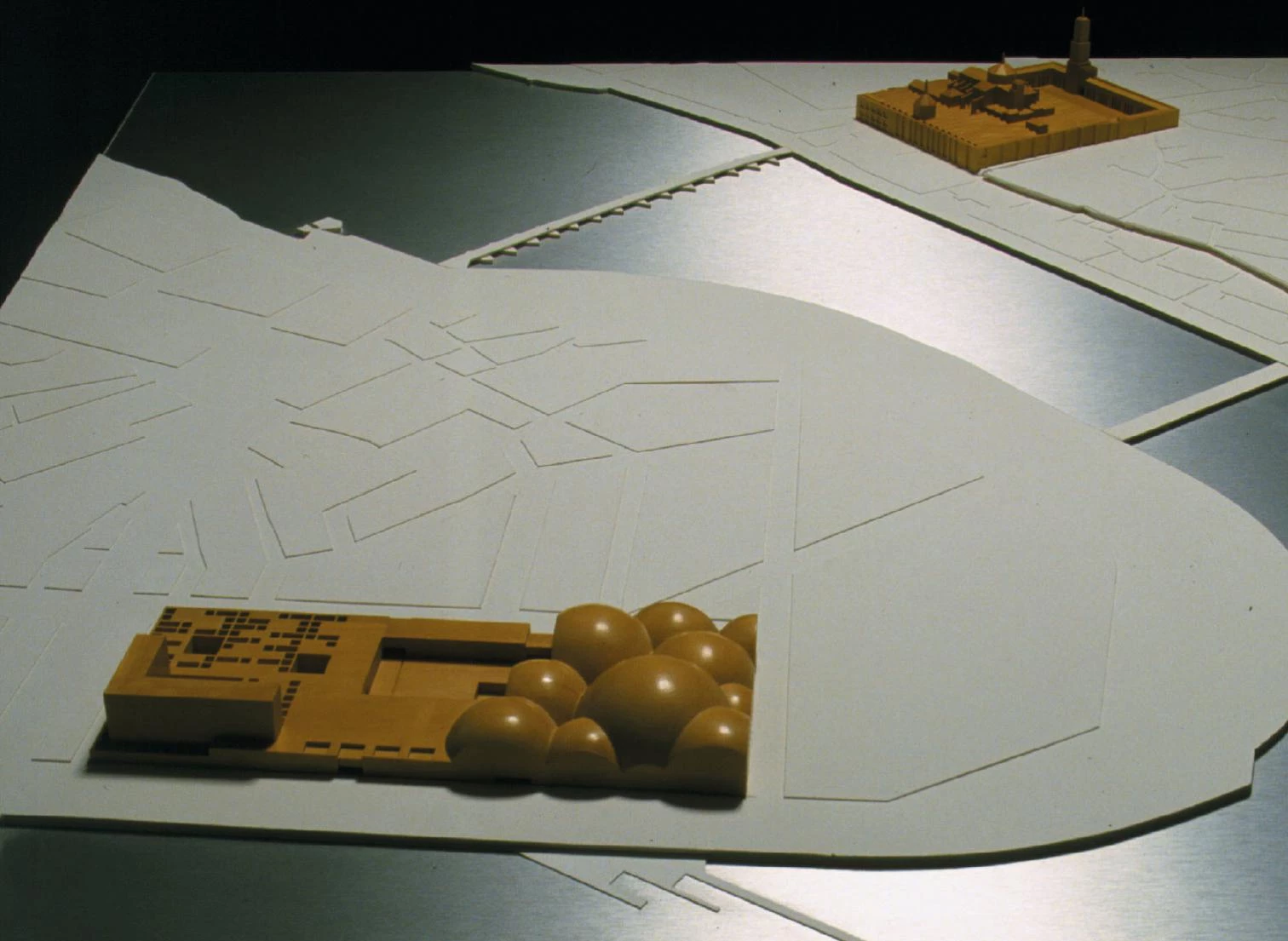

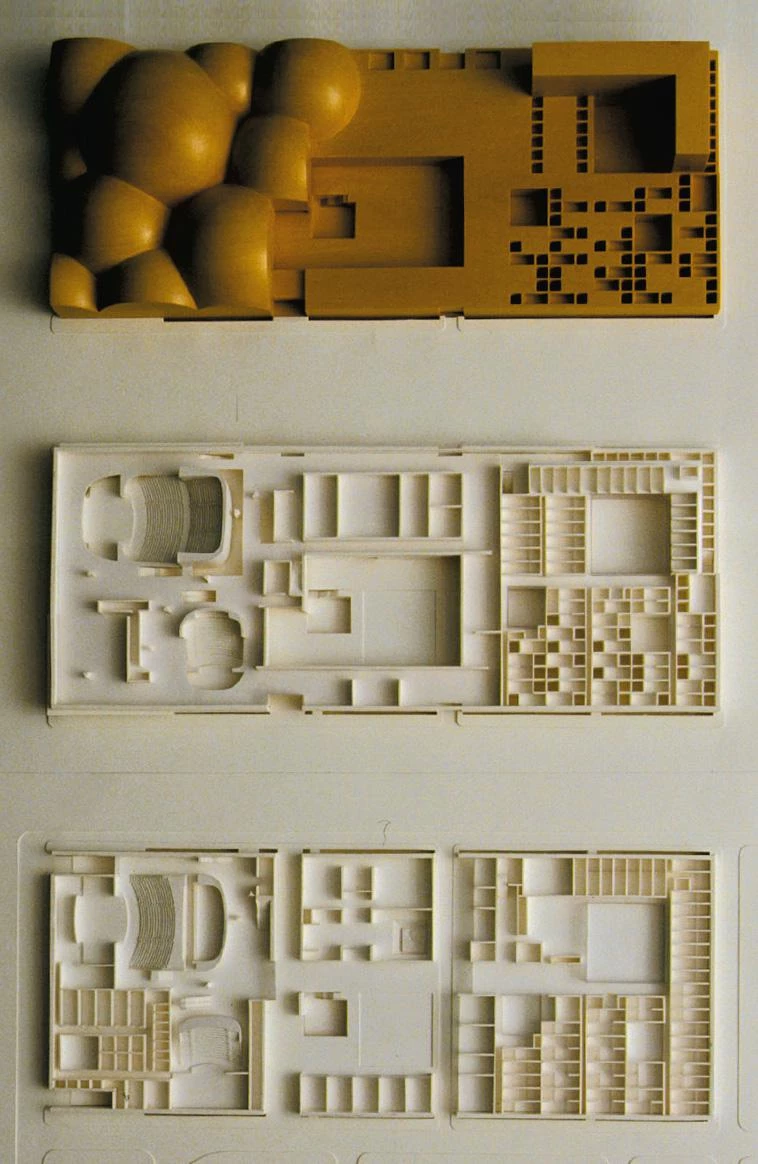

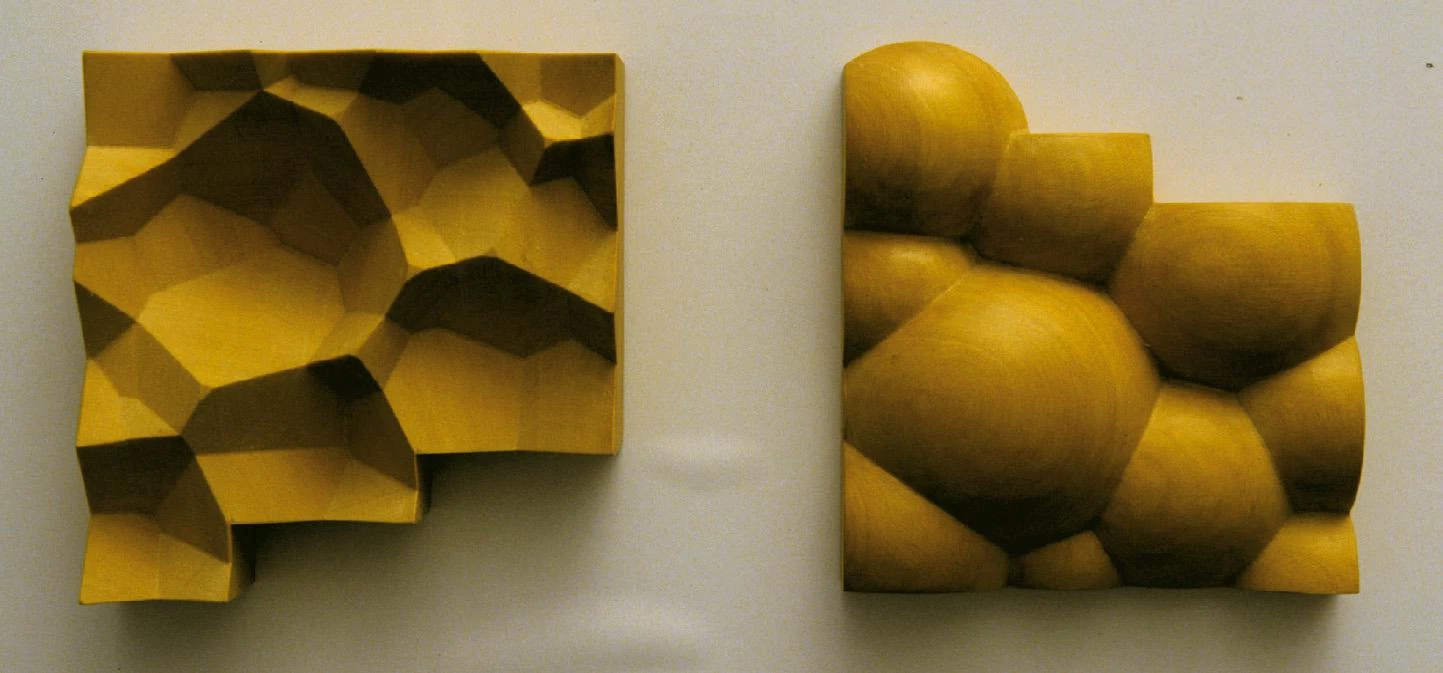

To close, the Madrid-based Rafael Moneo also proposed the total occupation of the plot, arranging the hotel in the form of a courtyard-pierced tap-estry (to which an L-shaped block was added), while the congress area was situated under an admirable formal invention, “a constellation of segmented domes”, similar to soap bubbles in their haphazard gathering, and to whose silhouette the whole image of the building was entrusted. The cluster of domes, clad outside in glazed ceramic tile and shaped inside as a random collection of irregular polyhedrons, is supported by a metallic structure placed between both surfaces, so that the form does not have a loadbearing character: boiling and embryonic, these tense bubbles are rather like cells in an urban blastula which grows and multiplies, spilling over the surrounding fabric with a formal ebullience that evokes the vigorous heartbeat of life in contrast with the geometric cashba lying at its feet.

From the opposite bank, the Mosque inspired the main features of the projects of Toyo Ito and Rafael Moneo: the first, a columnar hall with a glass minaret, and the second, a mat of patios and a constellation of cupolas.

“Whom shall we ask for news from Córdoba?” A quarter of a century ago, the poet Pablo García Baena deplored the decay of the city “while they dress her up in percalines / for a sinister touristic carnival”, and he recalled Góngora to describe Córdoba as the “the battered flower of Spain”. On the threshold of the 21st century, the quiet Córdoba of Manuel Machado raises her voice to seize her destiny and her river, a zealous guardian of her clas-sical and Muslim past who is willing to weave it with a project for the future. If her pulse does not tremble, Córdoba’s best days are yet to come.