Music in Flames

The work of Fernando Menis combines physical roots and mental freedom, tactile attachment to matter and visual imagination, close ties with the mineral landscape of the Canary Islands and a wide range of references. This unexpected architecture is at once geological and learned, rigorous and playful, insular and cosmopolite, and embraces the solid certainties of tradition to subvert them with irony and affection. On the firm base of a tenacious constructive, functional and climatic realism, Menis plays the serious game of language: the sculptural forms of concrete, the still movements of the steel curves or the warm and smooth skins of wood combine with the rustic order of masonry walls or stone plinths, peppering the ensemble with flashes of humor, sensuality, and emotion, in an architecture whose varied tributes to nature and history are summed up with realism and eloquence in projects that find, like their author, their foundation on landscape and culture, on matter and image. If the same could be said about this shared career, it is because there is a clear continuity between his choral and his individual career. On his own or in a team, Menis has created a manner that sets him apart as an author: quite something for a designer, and even more for an architect.

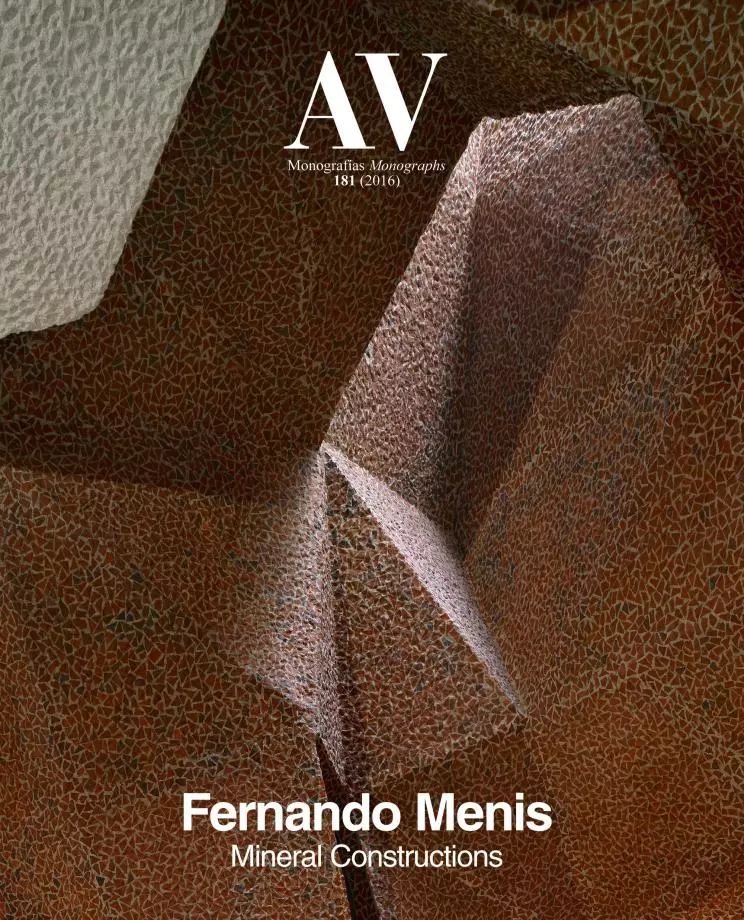

This megalithic and origamic language, able to bring together the heaviness of concrete and the light folds of a petreous scenography, joins muscular strength with aerial agility to (Mohammed Ali dixit) “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.” The boxer then called Cassius Clay explained in this way his historic victory against Sonny Liston, and something similar can be said of Fernando Menis. Brutal and delicate, his stereotomic and telluric architecture feigns floating at times, but only to strike our senses more efficiently. Cavernous more than solar, its interiors are animated by a black light that carves carefully sculpted forms where one often notices the traces of tools and hands. Mannerist rather than romantic, Menis’s work has known how to go beyond its volcanic and insular precinct to explore faraway sites, pushed by a crisis that has forced many to exit their comfort zone, but also moved by the clear conscience that his formal universe does not end at the archipelago’s perimeter. And yet, transformed into nomadic architecture, this unique oeuvre stays stubbornly true to its origins, always provocatively oxymoronic and also nurtured by the inner fire that consumes it. If Goethe described architecture as frozen music, that of Menis might well be music in flames.

Luis Fernández-Galiano