In 17th-century Holland, the microscope and the camera obscura for evermore changed the way we behold. The historian Laura J. Snyder describes this phenomenal mutation in how we perceive things through two figures who coincided in time: Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who with a lens discovered an until-then hidden world, and Johannes Vermeer, who with another optical device obtained a new manner of depicting light in paintings. Born in Delft within a week of each other in 1632, they lived there and had friends in common, although there is no evidence they ever even met. In the context of a scientific revolution that called for the observance, representation, and measurement of nature, both the developer of the microscope and the brilliant artist who used the camera obscura drew from the latest discoveries in the sphere of optics to stretch the reach of the gaze, inextricably marrying art and science.

Histories of art and histories of science tend to move on different rails, but with her erudition and narrative talent the American author braids together the instrumental advances that opened our eyes to the miniscule through optical tools which allowed more reliable renderings of the world, and explains how, just as philosophers of nature themselves tended to have some artistic training, painters took an interest in optical advances and became naturalists through their detailed portrayals of the biological and botanical universe. Leeuwenhoek worked with artists who were capable of drawing the microscopic world that his lenses captured, and Galileo, seeing lunar spots with his telescope, would never have been able to interpret them as shadows of mountains had he not in his youth received training in art. But there is no need to go far back to the dawn of the scientific revolution. Ramón y Cajal could not have so efficiently described the morphology of neurons if he had not also been an exceptional draftsman, and both my histologist grandfather and my microbiologist father captured what they beheld through a microscope by drawing.

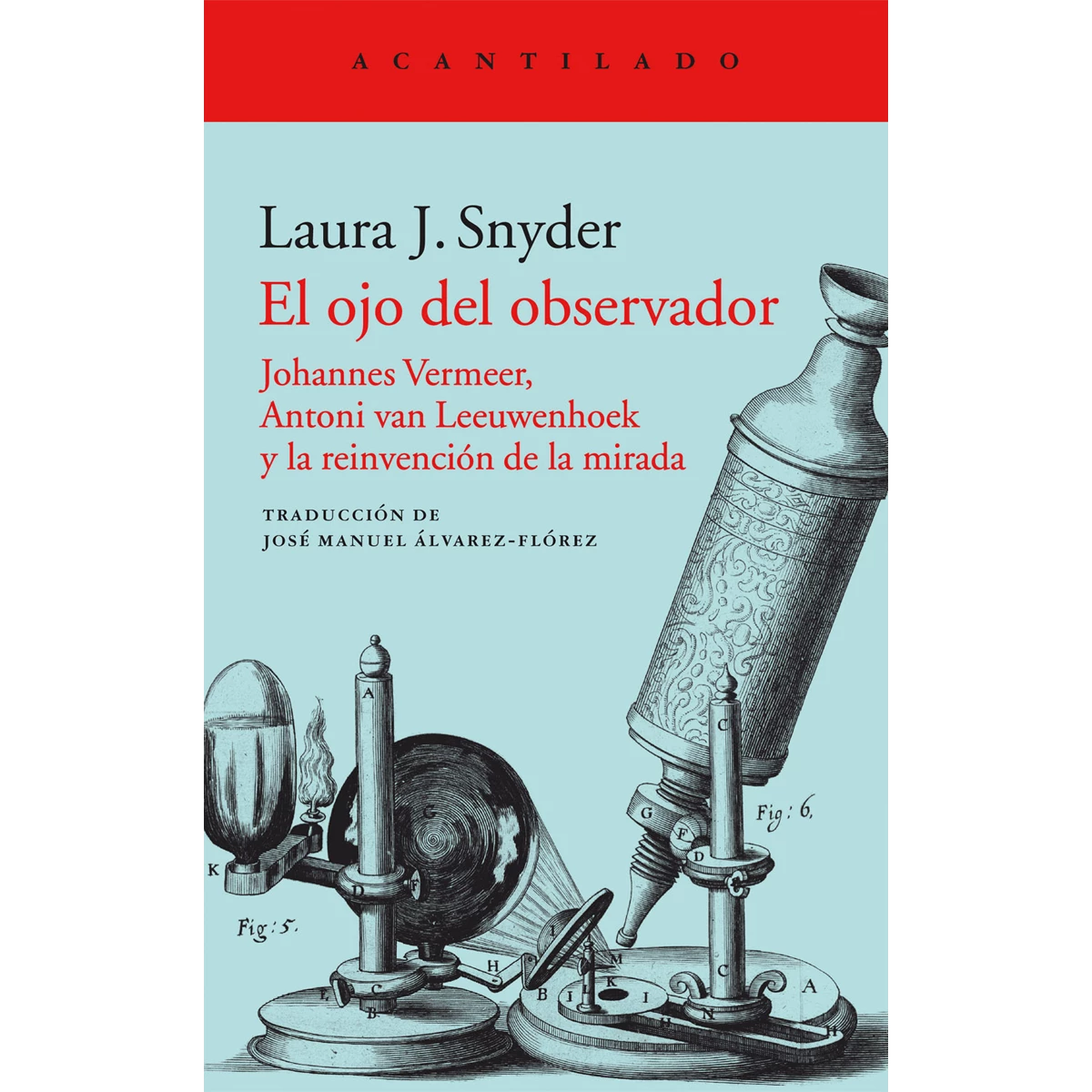

Snyder’s book, published in 2015 as Eye of the Beholder, reflects with intelligence and eloquence that revolution in the gaze, not to mention the link between art and science. Leonardo da Vinci advised painters to learn to behold by studying “the science of art and the art of science,” and this book’s parallel biographies of the two Delft geniuses provide an exemplary illustration. Leeuwenhoek, a keen observer, was not the only developer of the microscope (the Spanish cover shows Robert Hooke’s doble-lens version, while the over 400 built by Leeuwenhoek were single-lens) nor was Vermeer the only artist who worked with the camera obscura, so popular that a friend of our two subjects, the natural philosopher and art lover Constantijn Huygens, said that with its use, “all painting is dead in comparison, for here is life itself, or something more noble, if only it did not lack words.” But that the two coincided in space and time authorizes a search in 17th-century Delft for a new way of beholding that to this day continues to fertilize the gaze.