Eastern Matter

Four Experiments in Vietnam

Farming Architects, VAC Library, Hanoi (Vietnam)

One is hard put to name a country that has a more beleaguered modern history. The rapacity of the West sought to turn Vietnam into both a productive, profitable colony and a geopolitical outpost in the Far East. First to arrive were the French, who planted their flag on that beautiful and ancestral land in the 19th century, to not let go of it until 1954, after an absurd, sinister war; in their wake came the Americans, whose insatiable thirst for new Cold War tactics soon brought about the scorching war of napalm and Agent Orange, a cataclysm that would come to an end only in 1975, with the famous images of helicopters evacuating American officials and Vietnamese friendly to them out of Saigon.

The almost three million killed in that cataclysm – bound to the inertia of the Iron Curtain, which also dropped over the tropics – kept the country weighed down for two whole decades. Notwithstanding, and despite conflicts with Cambodia, tensions with China, and persistent hostility towards the United States, Vietnam had the foresight – like its great neighbor to the north – to initiate and implement a process which, without questioning the authority of the Communist Party, opened its markets to capitalism and embraced private property and foreign investment while continuing to take care of public health and education.

As a result, Vietnam today is one of the region’s economically fastest-growing nations, and also one of the most socially balanced, and this has had an echo in its architecture. Aware of realities but cosmopolitan in outlook, a generation of young professionals has faced up to and met the challenge – so common in non-Western countries – of combining international languages with regional constants, the use of technological innovations with loyalty to vernacular materials, and civic concerns with the pusuit of national identity; in sum, to apply the inevitable cliché, the inspiration of modernity with deep respect for tradition.

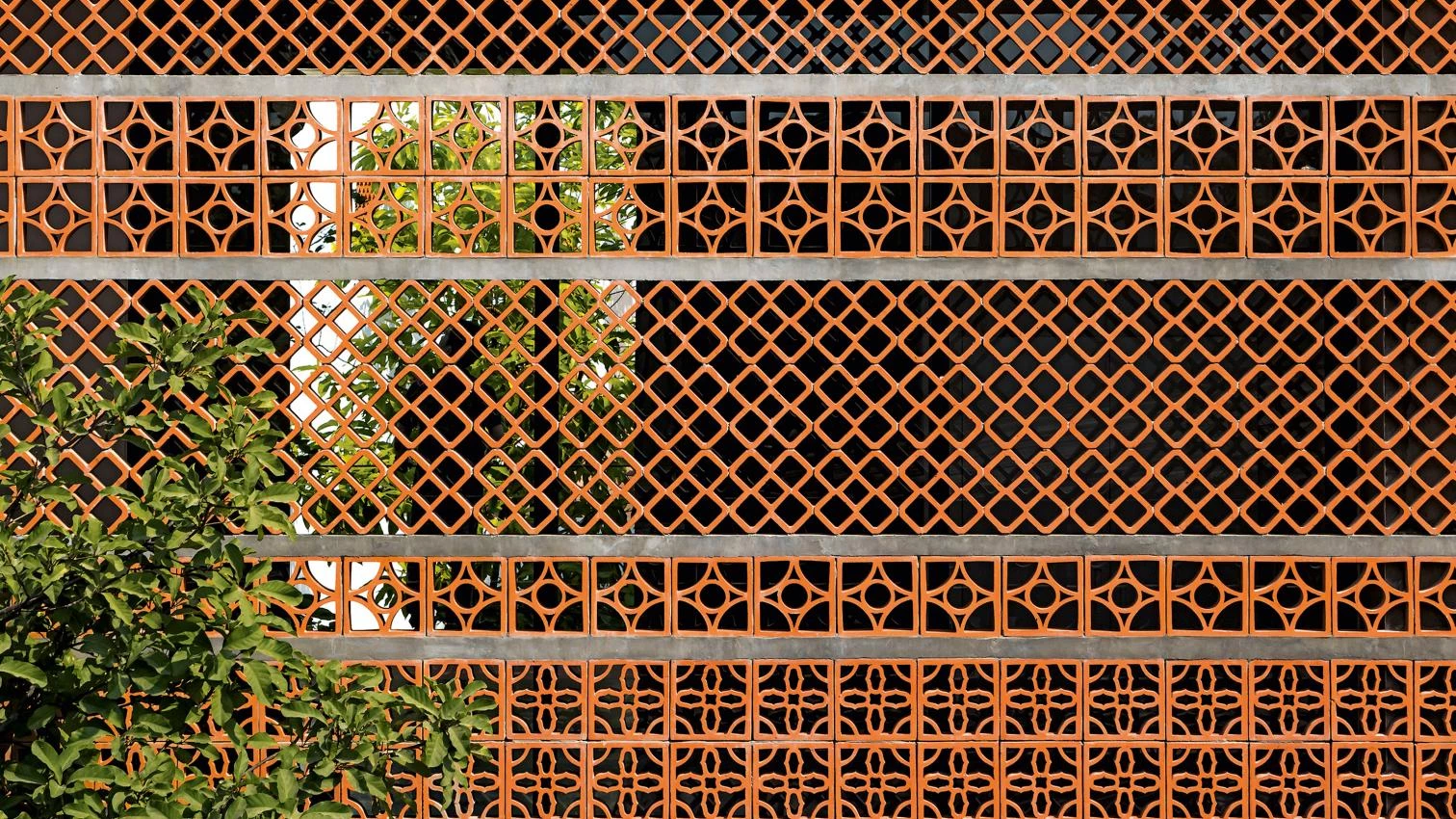

The four examples featured in this dossier illustrate such attitude of experimental conciliation, in which climate and the tropical landscape are addressed and where space and materials are worked out on a sensory but also symbolic note. In the Urban Farming Office in Ho Chi Minh City, the firm VTN Architects has made tropical flora the building’s icon. A similar strategy defines the Jakob Saigon Factory in Thuận An, a work of G8A Architects. For its part, the Premier Office building in Ho Chi Minh City, by Tropical Space, brings in ventilation through porous brick lattices, while the Đạo Mẫu Museum in the rural outskirts of Hanoi, by ARB Architects, colonizes its exuberant environment by means of pavilions raised with tiles taken from the roofs of abandoned houses, evoking the genius loci through entropic, memory-storing matter.

Sanuki Daisuke architects, Apartment in Binh Thanh, Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam)