Freight train of the New Silk Route (Belt and Road Initiative) between China and Kazakhstan © Samuel Sánchez / El País

Trade unites, and its paths weave a web that holds the world together. Faced with shrinking globalization, with many countries preferring geographical or ideological proximity in their exchanges, to defend the links created by commercial traffic is to defend bridges over walls. Europe’s paper currency shows bridges and windows as symbols of openness, but Fortress-Europe advances limiting the movement of goods and people, and turning its back on the drama of migration. In this context it is worth to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative, a genuine Marshall Plan for infrastructure construction launched by China in 2013, and in which today 150 countries, representing 75% of the world’s population and 50% of its GDP, are participating. These new silk routes, which follow in the north the land itineraries of Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta, and in the south the sea paths of admiral Zheng He, hope to strengthen the economic and political ties between Asia, Africa and Europe, something desirable in our time of disconnection.

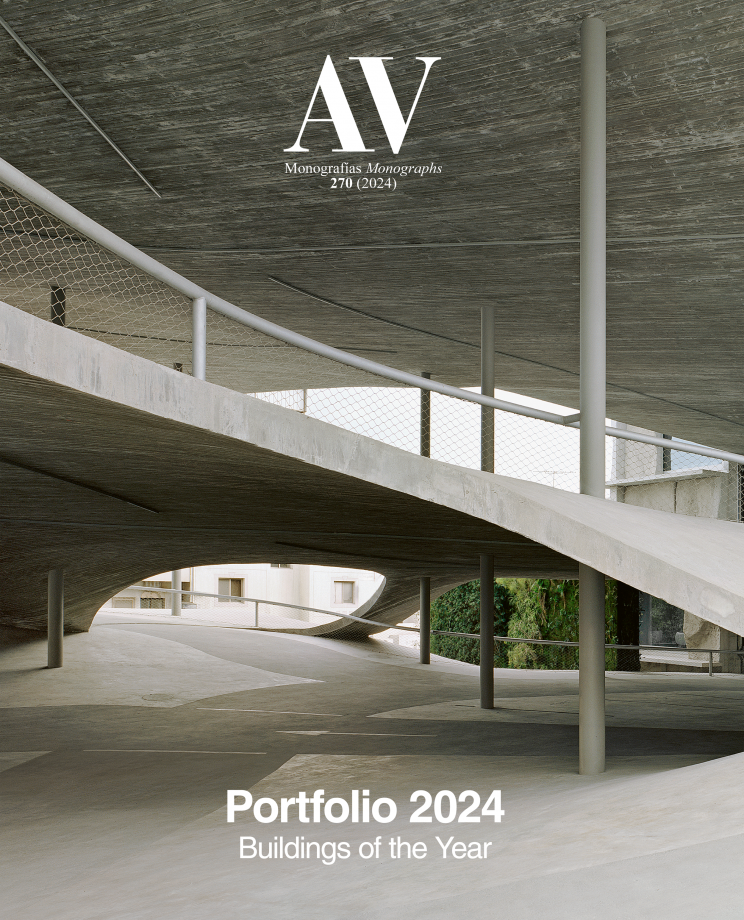

Though Europe is reluctant to be seen as a peninsula of Asia, its demographic contraction, economic decline, and loss of influence mark its subaltern role in what Halford Mackinder called the ‘World Island,’ formed by the three geographically adjacent continents that the Chinese initiative tries to tie with infrastructure: on land, like the freight railroad of the Belt that travels 13,000 kilometers from Yiwu to Madrid, connecting China with Europe through the steppes of Kazakhstan or Russia; but maritime too, because the new ports along the Route serve the 105.000 vessels – container ships, tankers or freight ships – that in the world transport 80% of trade by volume, and 50% by value. Oceans today are, as rivers were in the past, essential paths of trade, even though the present maritime disorder forces to recall the freedom of navigation theorized by Hugo Grocio with his Mare liberum of 1609 (building on the bases of the international law established in Salamanca by Francisco de Vitoria), and that now the US Navy protects.

This disorder, which includes many ships of dubious ownership and flag of convenience, like the one which lost containers filled with plastic pellets off the coast of Galicia, becomes evident in the current insecurity in the Red Sea, where the Houthi attacks in retaliation for the Gaza war block the path towards the Suez Canal; or in the navigation difficulties in the Black Sea, filled with mines and vessels damaged in the Ukrainian war. And beyond conflicts there are geopolitical risks like those affecting the South China Sea or the Strait of Malacca as a result of the tensions over Taiwan, or alterations due to climate change, like water reduction in the lakes that feed the Panama Canal locks, threatening traffic, something we experienced last summer when the loss of water made Rhine navigation impossible. But the paths of trade also go through the ocean beds, with the cables and pipelines we saw sabotaged in the Baltic or the North Sea, and nothing today is as critical for global governance as preserving the land or maritime routes through which information, goods, and people circulate.

The vessel Toconao lost a container bearing plastic pellets along the Galician coast