Call me Glenn

The metal and glass houses of Glenn Murcutt are as warm and direct as their author, an Australian who has become a world figure while working on his own.

Mr.Murcutt... “Call me Glenn!” At first con-tact the architect demands colloquial cordiality, dropping formalities with the unmistakable clarity of one who likes to go straight to the point. The works of Glenn Murcutt, mostly houses, come across with the same kind of immediacy, avoiding conventional formalisms and proceeding to the core of the matter with expeditious naturalness. At 65, the admired Australian master dresses like a well-off and jovial farmer. He is away often, traveling to comply with his public or teaching commitments in the northern hemisphere, but his regular absences from Sydney do not seem to affect his one-man stu-dio too much: clients coveting his domestic sheds of glass and metal are resigned to waiting years for their turn. It is precisely this décontracté mood of a laid-back yet hardworking country gentleman that his buildings have. But their friendly simplicity is only the relaxed countenance of a vast wisdom on construction, climate, and landscape.

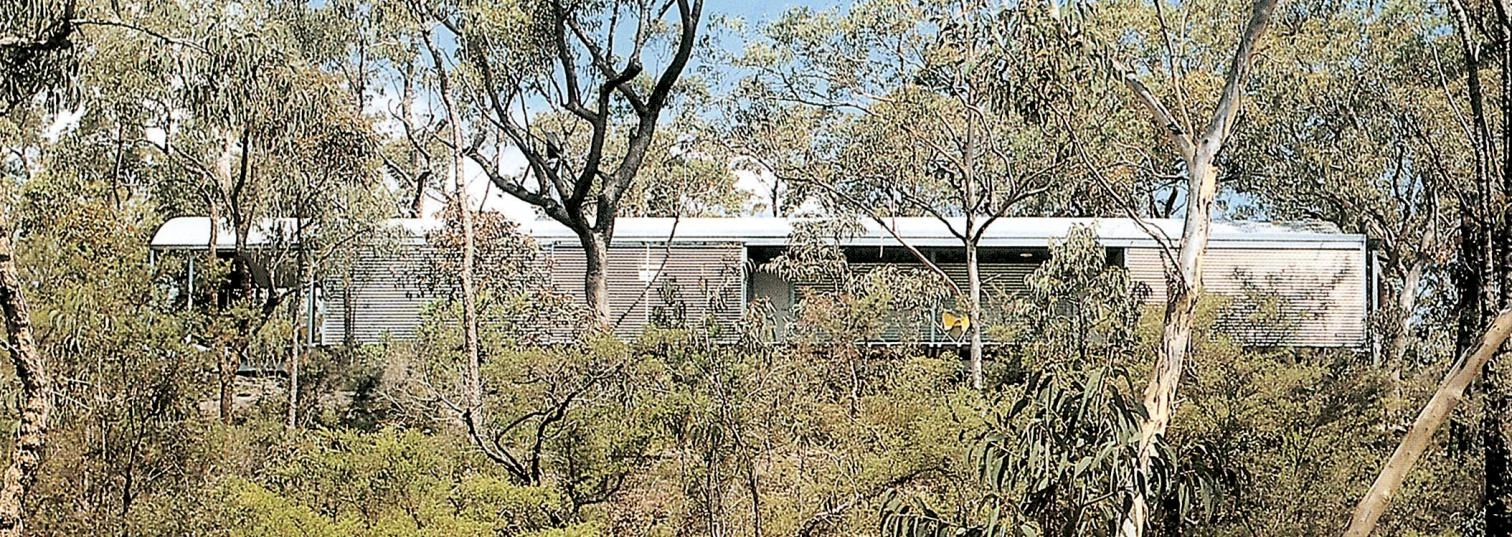

Among eucalyptus, like the Ball-Eastaway house, or in open landscapes, like the Marie Short house: Murcutt’s domestic oeuvre shows an ‘Australian way’ of perceiving architecture as an activity intimately linked with environment.

Though born in London during a trip of his parents, Murcutt is as archetypally Australian as his works. Australian, that is, not in the Crocodile Dundee manner that tritely gets around in these antipodes, but as a combination of Russell Crowe’s intelligent integrity and Nicole Kidman’s emotional exactitude, complementary representatives of a cosmopolitan Australia that has long left behind its ominous history as a British penitentiary colony, its anthropological myth of aboriginal purity, and its romantic utopia of the last frontier of the planet. The territory of adventure is today an urban country, with the majority of its 20 million inhabitants living in metropolitan areas, and where the existence of immense stretches of unpopulated land combines with rigorously restrictive immigration laws that, with episodes like the denial of entry to the ship-wrecked Afghans picked up by the Norwegian freighter Tampa, or the prolonged internments of illegal immigrants from Asia in detention centers, have tarnished the smiling image of an Australia of kangaroos and tennis players.

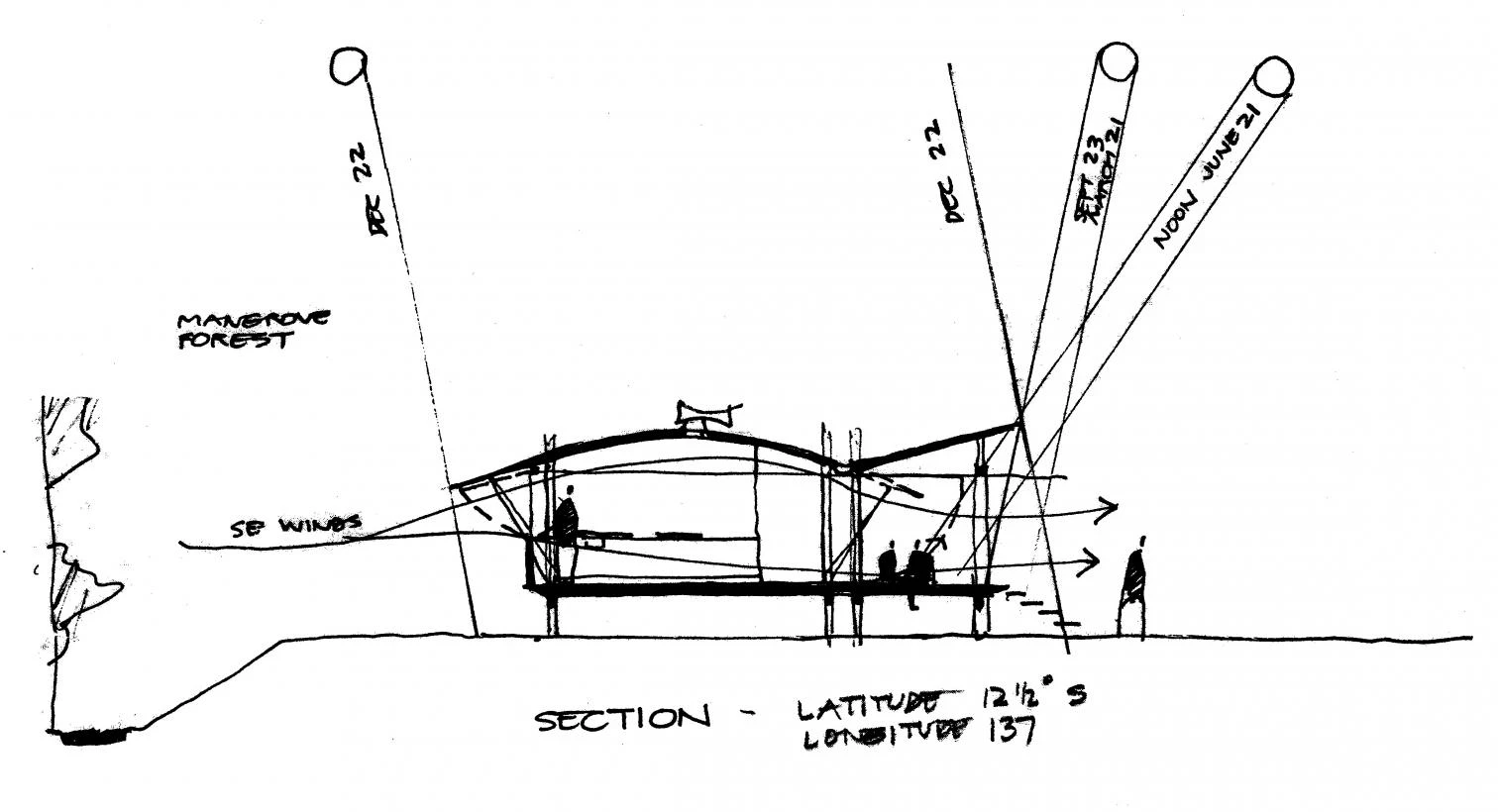

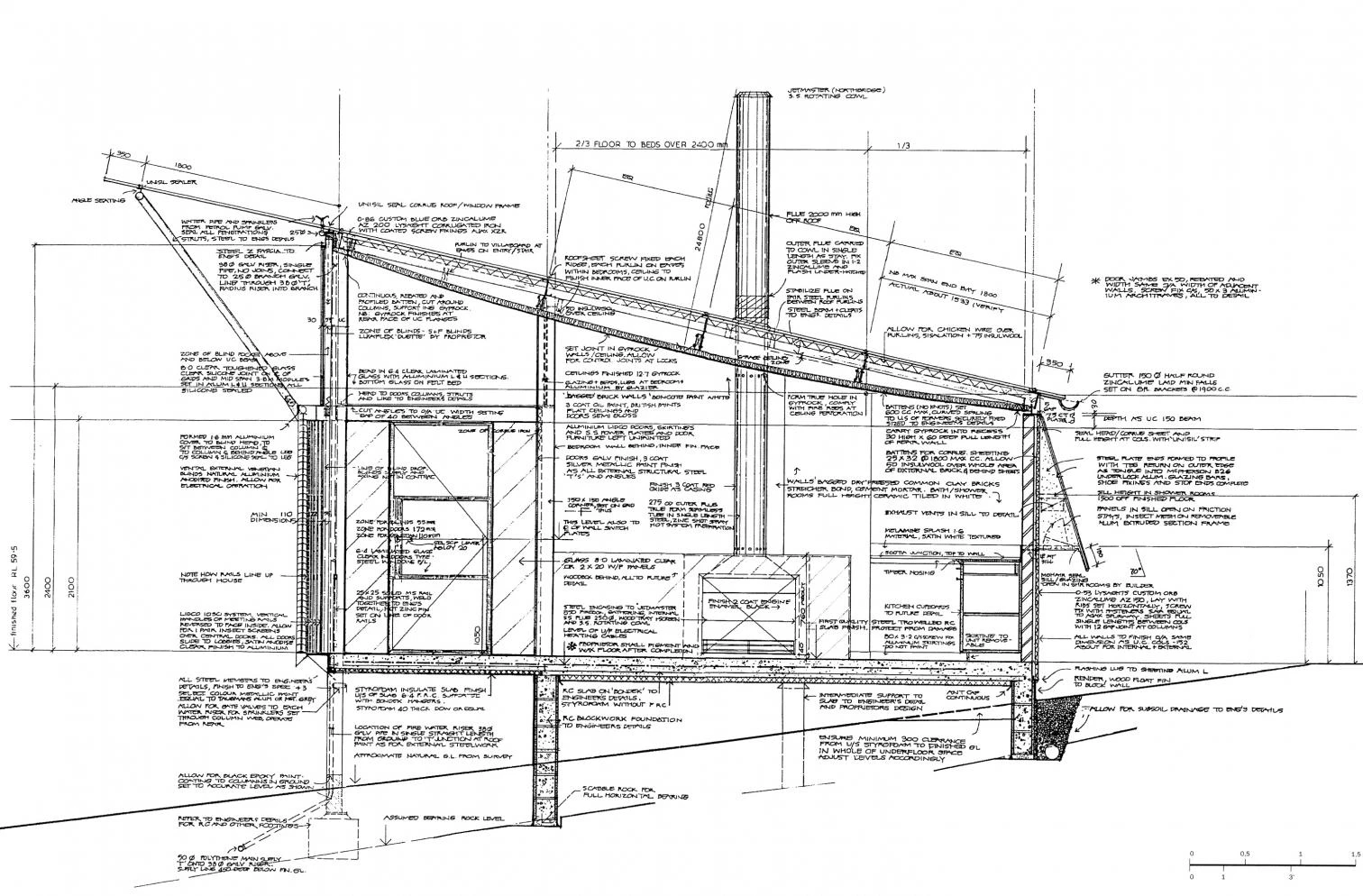

Sections sum up Murcutt’s climatic interests and construction methods: in the sketch, the Marika-Alderton house; below, the Magney and Fletcher Page houses; opposite, the Simpson-Lee house completed and on paper.

The architect’s austral land is rather the one we got to know through the Sydney Olympics, a multicultural country with a robust economy and vast spaces that tries to combine prosperity with respect for nature, and where the pioneer spirit remains present in many fields of life. Daring and self-sufficiency were indeed values inculcated early on in Murcutt, son of an admirer of Thoreau who was suc-cessively a gold seeker, a carpenter, a developer, and an amateur architect.With this father the young Glenn became familiarized with construction materials and techniques. Architectural studies in the fifties converted him to the Miesian gospel then being preached in the California of Neutra and Ell-wood, and training in different Australian and British offices in the sixties reinforced his adher-ence to the relaxed and regional modernity of the USA’s Pacific Coast – enriched with the inevitable Japanese echoes and nuanced by an intimate affinity with the Scandinavian architectures of the time, whose humanist, vernacular empiricism and devo-tion to landscape had great impact in Australia, coinciding with Aalto’s popularity and Utzon’s presence in Sydney during the early years of the con-struction of the emblematic opera house.

When he set up his own practice in 1969, Mur-cutt was without a doubt already an experienced professional with refined tastes, but the first hous-es he built – for himself, his brother Douglas, and Laurie Short – were exercises feeding from Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House or the Case Study Houses of California, rigorous glass boxes that al-lowed only a cursory adaptation to climate in the projections and porches. The Australian’s point of inflection came in 1973, after a European trip in which he discovered the Maison de Verre – a hygienist and mechanistic experiment built between 1927 and 1931 by Pierre Chareau, which has also inspired a good part of 20th century high tech, from Prouvé to Foster. The poetic and pragmatic rationalism of the Parisian house encouraged him to en-rich the modern universality of the geometric grids with new material and formal tools: catalog products, warehouse latticeworks and corrugated metal sheets which transform the transparent boxes into extruded sheds with curved roofs and an industrial look, anonymous and exquisite hangars first mate-rialized in Marie Short’s house at Kempsey (later acquired by the architect), and which thereafter proliferated in a splendid outburst of elemental and elegant domestic architectures in harmony with the sun, the wind, or the rain of the landscapes of west-ern Australia, from the eucalyptus forests where the Ball-Eastaway House is hidden to the arid coasts where the Magney House stands.

It is these light, ad-hoc, factory-like shelters that have made Murcutt a cult architect. But the popu-larity of this industrial vernacular of meticulous construction, impeccable climate control, and seamless adaptation to landscape cannot be separated from the unique work method of the Australian architect. With neither assistants nor collaborators, he both draws up projects and directs them by him-self, never delegating a decision, assuming full personal responsibility for each and every step of the process. From the rendering of the plans (which he has managed to reduce to 3 or 4A2 sheets per house, and which contain as much the 1:100 floor plans required by the urbanistic authorities as the 1:20 section where all the working details are laid down) to the supervision of the last screw, everything is en-trusted to a single person, the architect, who in this way achieves exceptional creative and quality control over the work while putting forward a rare model for the practice of the profession – a model apparently archaic but proven by the Murcutt ex-perience to be exemplarily plausible.

If Madrid’s ARCO fair in February is devoted to Australia, the Sydney Biennial will open in May under the motto “(The world can be) Fantastic,” and this optimistic affirmation faithfully describes the work of Glenn. Against the discouragement and cynicism of so many who are overwhelmed by the demanding complexity of contemporary building, the austral adventure of this architect of the an-tipodes deserves to be a reference for reflection.