The Genius’s Ashes

In England there is no Escorial. There is nothing of such austerity and such rigour. Overwhelming greenness - all those lawns and all those trees - may be scarcely compatible with any display of relentless grandeur; and this is, perhaps, why the late James Stirling (whose pursuit of grandeur was far from excessive) obtained so little work in the country of his domicile.

Bernard Berenson somewhere pronounced that English art has always displayed a tendency to ooze prettiness; and, although this characteristic demureness - Salisbury versus Orvieto - may often be a virtue and many persons have found it to be so, for others (Matthew Arnold’s born lovers of the idea, born haters of the commonplace?), it will certainly come to resemble a stifling cocoon. They want none of it, or little more than the very minimum; and it is no doubt what Arnold designated as this ‘remnant’ of English culture which, in a wider and different context, may serve as partial explanation of both the American Declaration of Independence and the existence of the former British Empire. Indeed one can almost hear the clamour for escape voiced by colonialists and imperialists alike. “Don’t fence me in with all those interminable hedges,” is what one hears them say, “if not Italy, then at least give me the wide open spaces of the unknown.”

And, then, what about Albion perfide? And did the French get it right? Or did they get it wrong? Wrong, I think, as regards politics, where - in spite of their many errors of judgment - the English have rarely been malevolent and never possessed that capacity for secrecy which makes conspiracy theory possible. But about English architecture? And had the French not disdained to direct their attention towards it, they might have discovered a highly rewarding argument. For, as regards architecture, the English - often believing themselves to be so concerned with fair play’ - seem, almost congenitally, to have been unable to comprehend the rules of any game which might ever have been imagined.

But yes. And, again and again, there seems to have been displayed a willingness to change every rule well before any game is complete. “Let us have no use for undue cerebrality,” so declared the alternative version of la voix d’Anglaterre; and it will be well to listen to it. “We are reasonable empiricists. But are we not? And, if we begin our game as though we are playing football and continue it as though we are playing chess, should there be any reason for serious dismay? But are we not captivating and can you not be sure that the results of our endeavours will be ingratiating and charming?”

But surely, in architecture at least, this almost sublime disregard for any traces of intellectual consistency - and this is London - had the French been able to discern it, has been le vrai Albion perfide.

Now Jim was conceived in New York, born in Glasgow (two years before he was willing to admit), brought up in Liverpool and didn’t arrive in London until he was about twenty-six years old. Then, in his early formation, apart from being a devotee of Le Corbusier, he was militarist and chauvinist, aboriginally ‘British ’ (an attenuated physique and a huge mustachio at this period), skeptical, abrasive, and never completely at ease with the more ‘English’ presumptions of London. In short, he was almost the provincial hero arrived in the great city from a novel by Stendhal or Balzac - a predicament which can only be French or English, in the end the only two countries where one city supremely prevails.

And did Jim despise London? I scarcely think so, though I have tried to indicate ample reasons for such a possible response. Rather, I can only suggest that my highly talented friend (at that early time more talented than capable?) was largely unaware of the intrinsic difficulties which, in England, must lie ahead for someone of his particular temperament, difficulties of socio-aesthetic consensus which, later, he came to detest.

However, all of this is now a very long time ago; and, in a few words, what else to say?

That Stirling, a fountain of originality, breached the normally garrulous operations of English architecture? That he belongs to the very few who have done so? That these might be: Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor, the icily Scottish Robert Adam (apex of the Edinburgh Enlightenment), possibly George Dance, certainly John Soane and, after him, the fastidious and Frenchified Cockerell and the Gothic Revival tough guy, Butterfield?

But, of course, there is no doubt that Jim belongs to this company who, all of them, must have found the, allegedly, supreme English architect, Christopher Wren, more than a bit tough to take, a climax of English non sequiturs. “But isn’t it heart-rending,” this is Jim on St. Paul’s Cathedral, “a very great dome; but, down below and inside out, doesn’t it look as though he were a pastry cook determined to use every piece of leftover dough?”

The time was July 1959 and we had just returned from a short trip to Paris where, in quick succession, we had seen Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre and Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaoul and where Jim’s normal astringency had become exacerbated by an inspection of the Val-de-Grace which, back in London, lead to the inevitable comparison of François Mansart’s wholly unitary conception with Wren’s curiously additive accumulation of incongruities. And this is to insist upon Jim as an architectural connoisseur.

He knew where all the bits and pieces of St. Paul’s came from: for the west front a combination of the east facade of the Louvre and Sant’Agnese in Piazza Navona; Pietro da Cortona’s semi-circular of Santa Maria della Pace for the transepts; and, for less eminent areas, the facade from Palazzo Thiene Vicenza and a casual quote, a false perspective window from Palazzo Barberini. And he was prone to popular taste which acclaims this strangely incompatible, and highly literal, collection. No, no, never Wren. Just Hawksmoor all the way.

I think that, as he grew older, Jim’s estrangement from what seem to be the endemic propensities of English architecture, particularly that tendency to articulate and to multiply parts, became all that more profound; and, no doubt to this, one may attribute his growing celebrity in foreign societies - Germany, the United States, Italy - where the ‘standards’ of Englishness are, possibly, seen less as a norm than an as aberration. And, if you add to this a distress related to what he perceived to be English deterioration, then the increasing forays of Jim in to the auction rooms are abundantly to be explained. He bought what he genuinely admired and he bought obsessively; but was not this delirium of acquisition at least partially a compensation for all those buildings which, in the United Kingdom, never came his way?

As an architect, so he was as a collector. He was addicted to almost everything glittering and shiny, well made and classically big. At the scale of objets this might mean René Lalique, Louis Comfort Tiffany, post-Napoleonic Paris porcelain, the best of English silver and candelabra by Thomire. But the whole scene was pretty august; and then, alongside this, there was his further passion for the most monumental and the most heavy of Empire and Regency furniture - Georges Jacob, Thomas Hope, George Bullock, George Smith - and it was this brilliant amalgam which came to comprise his own personal theatre and museum.

With its massive and primarily Empire component and with its many local suggestions of Art Nouveau, one might understand this particular domestic arena to have come into existence as an act of justification, as an apologia pro vita sua, as a private analogue for the grand public performance which, in England, was never to be made.

And about Stirling’s later buildings?

I have not seen the Wissenschaftszentrum in Berlin, though I greatly admire its accomplished and evocative distributions; and, then, there are the three American buildings.

At Harvard, the Sackler Building has made a great bridge between the Fogg Museum and Gund Hall; and, with its representative facade - a vertical presence, and its broad stripes behind - a horizontal support accommodating an eccentric fenestration, it has still barely received the acclaim which it deserves.

At Rice, in that quasi-Byzantine milieu, the extensions to the architecture building are so unassertive that it becomes not easy to discover them.

At Cornell, where the Performing Arts Centre, the best recent building on the campus, should - perhaps - still be a little better than it is. A very pretty horseshoe theatre, based upon the Cuvilliés theatre in the Munich Residenz; a very pretty peristyle which owes more than a little to Leon Krier; a great site; potentially a spectacular view; however a view which remains fatally blocked by a few unimportant, though sacrosanct, trees. Wretched trees! But, short of poisoning them (during the hours of darkness?), there remains nothing to be done.

And, then, the Germanic lands!

So what did Jim find in Germany and what did Germany find in him? And I can only confess that 1 don't know. But, apparently, with German clients he could be completely himself. Apparently they accepted his physical and his intellectual largesse, his triumphant magnanimity, in a way which the English, inhibitions aroused, could scarcely understand.

But, all the same, just why was the Land of Baden-Württemberg so very grand? And just how did so many politicians permit their suspension of disbelief?

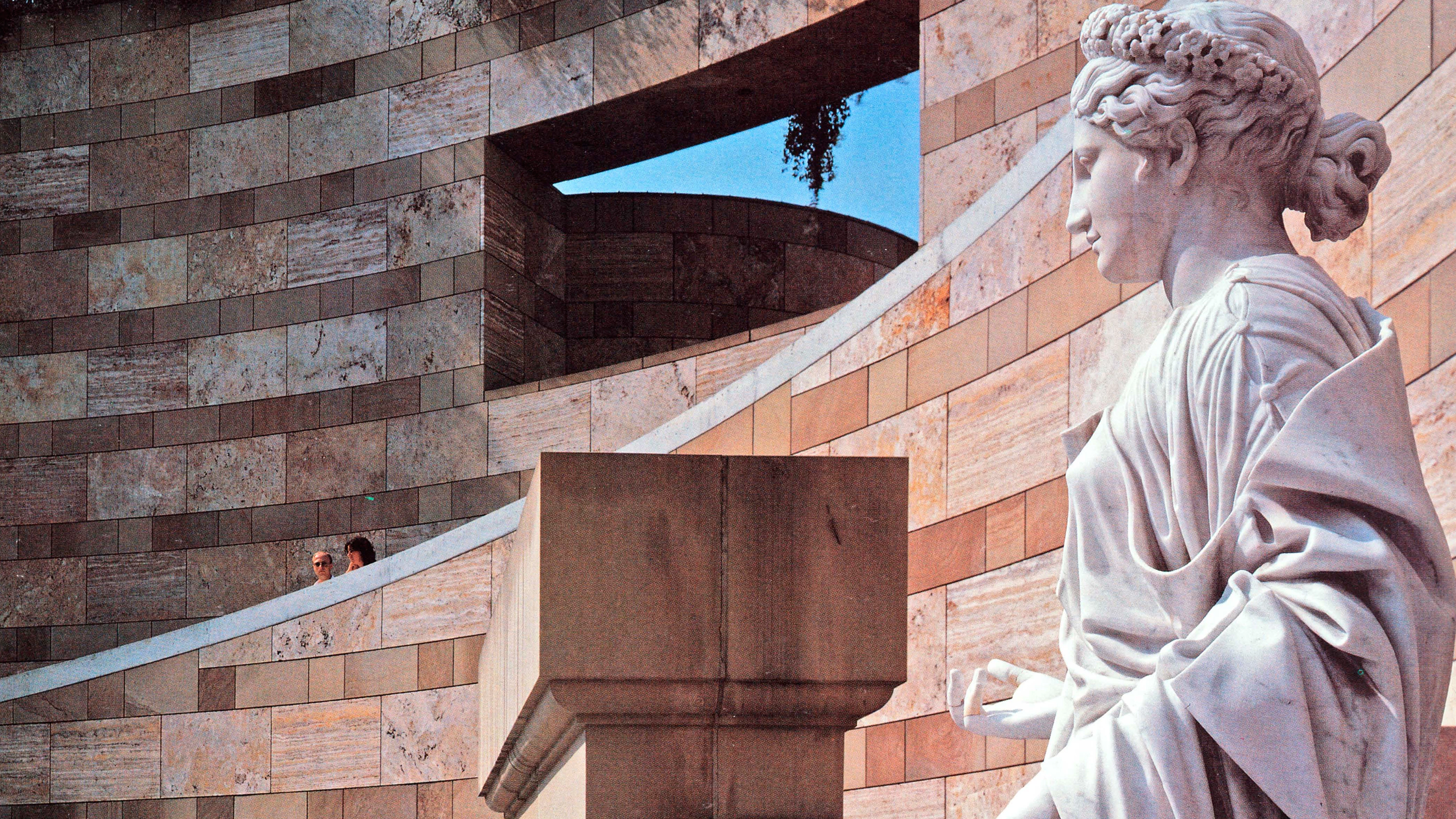

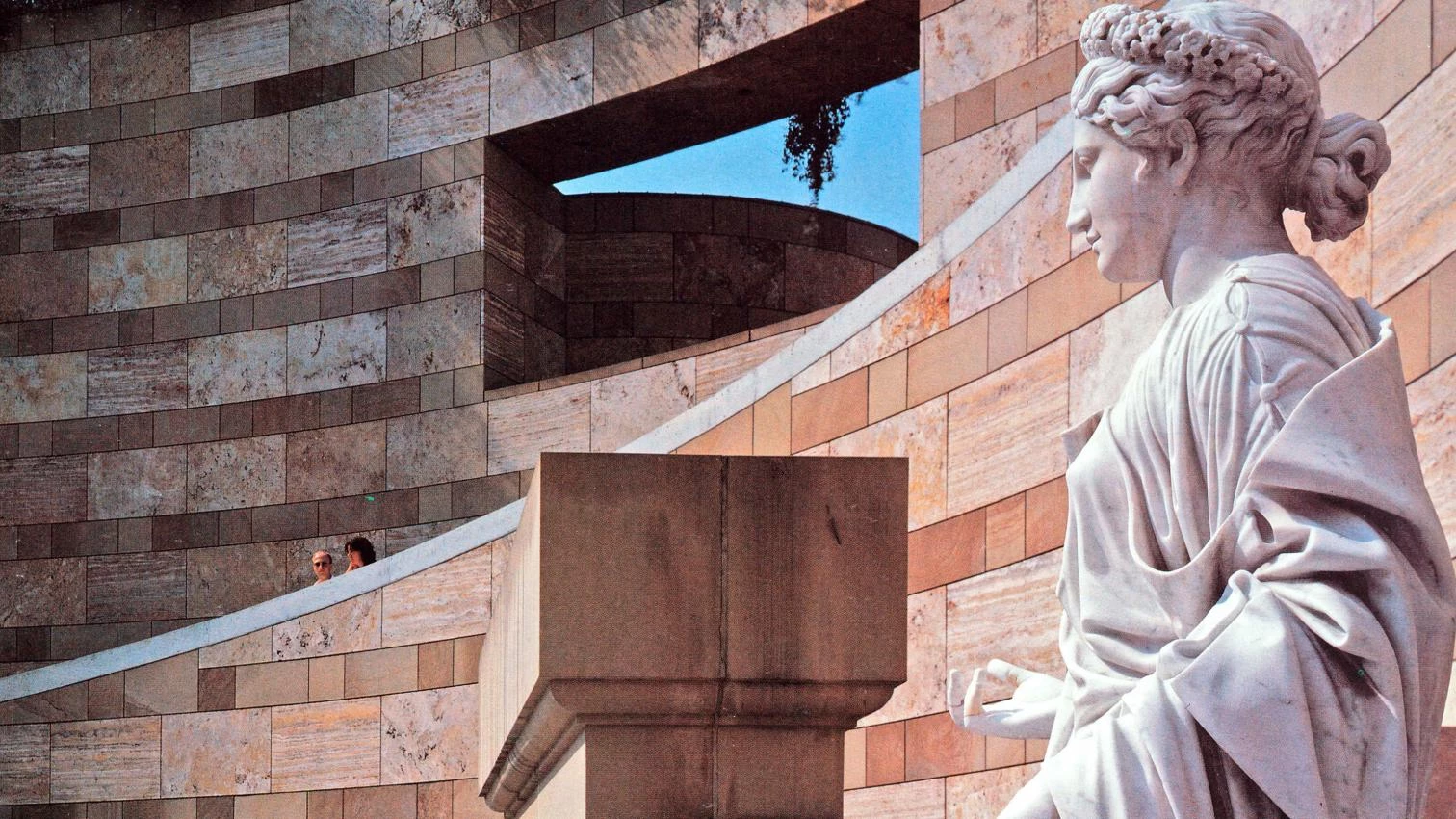

Jim insisted that I accompany him to Stuttgart when the Staatsgalerie was still under construction; and I have since been back three times, the last time when Jim was also present and we drove out to Ludwigsburg and up to Schloss Solitude. And, finally, I can only comment upon Stuttgart as a version of the sublime. A work of genius, it has become a memorial to genius, almost like something which ought to belong to the Germanic lands in the age of Sturm und Drang; and now, having seen it on four occasions, I can only add that there is no recent building which has so overwhelmed and consumed me since I visited Le Corbusier’s La Tourette in 1960 and 1961.

But the Staatsgalerie transcends all of the plausible categories of criticism. It is what it is. It is something beyond dispute; and it is for this reason that it is there that I would like to see the ashes of my friend deposited. There is that little semi-crypt which one approaches down a few steps just to the left as one enters the circular courtyard - an episode which still requires explanation; and, surely, it is there that one might find a plinth, empty of all inscription and a Roman cinerary urn - for Jim.

And, otherwise, what may I say but almost? Almost himself began his career as a student of mine - almost but not quite; and, almost, myself will close my own career as a student of his - again but not quite. And, meanwhile, there remains that brilliance, that truculence, that ongoing argument, lots of things looked at together and a ceaseless hospitality such as, otherwise, I have never experienced and can no longer hope to enjoy.