At the start of each decade, the book is predicted to die in the course of it. But this terminal patient is in good health, and since the definitive replacement of the roll by the codex in the 4th century, pages folded, sewn, and bound have been the principal instrument for passing on knowledge – handwritten at first, printed since Gutenberg. So it might not be a bad idea to begin the 100 book sections we intend to publish during the new decade with a review of two recent British publications that focus on the fascinating life of manuscripts, those early codices that chart the history of thought, some of an illustrated beauty that makes them exquisite objects. In Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, the antiquarian and librarian Christopher de Hamel deals with a dozen of those illumined codices of the Middle Ages, all of them of dazzling artistic quality, and describes his relationship with them as rare encounters that enable him to explore their exceptional travels through time. And in The Map of Knowledge, the young historian Violet Moller uses three scientific manuscripts, successively copied in seven different cities during the medieval period, to explain how classical knowledge was conserved and conveyed from Antiquity to the Renaissance.

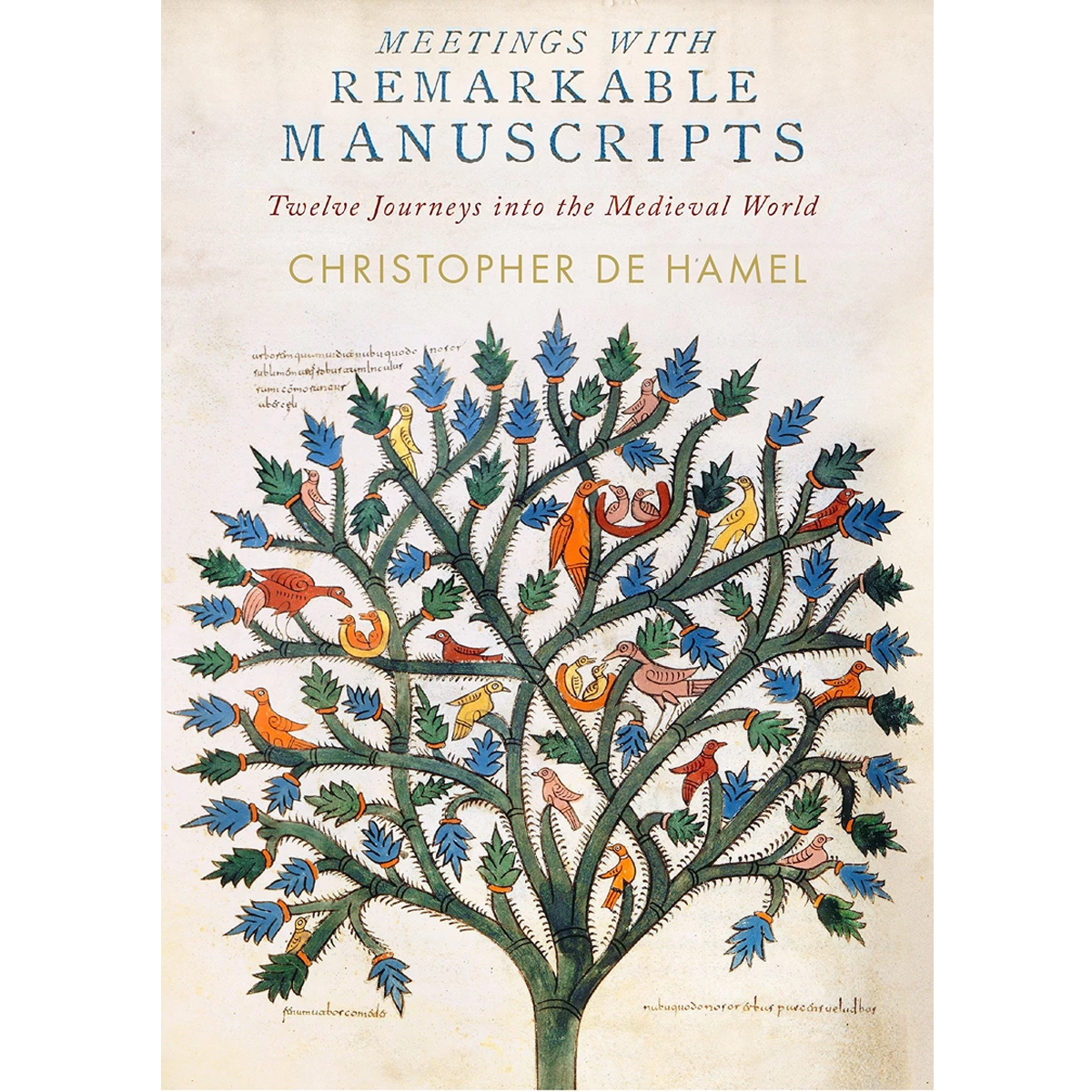

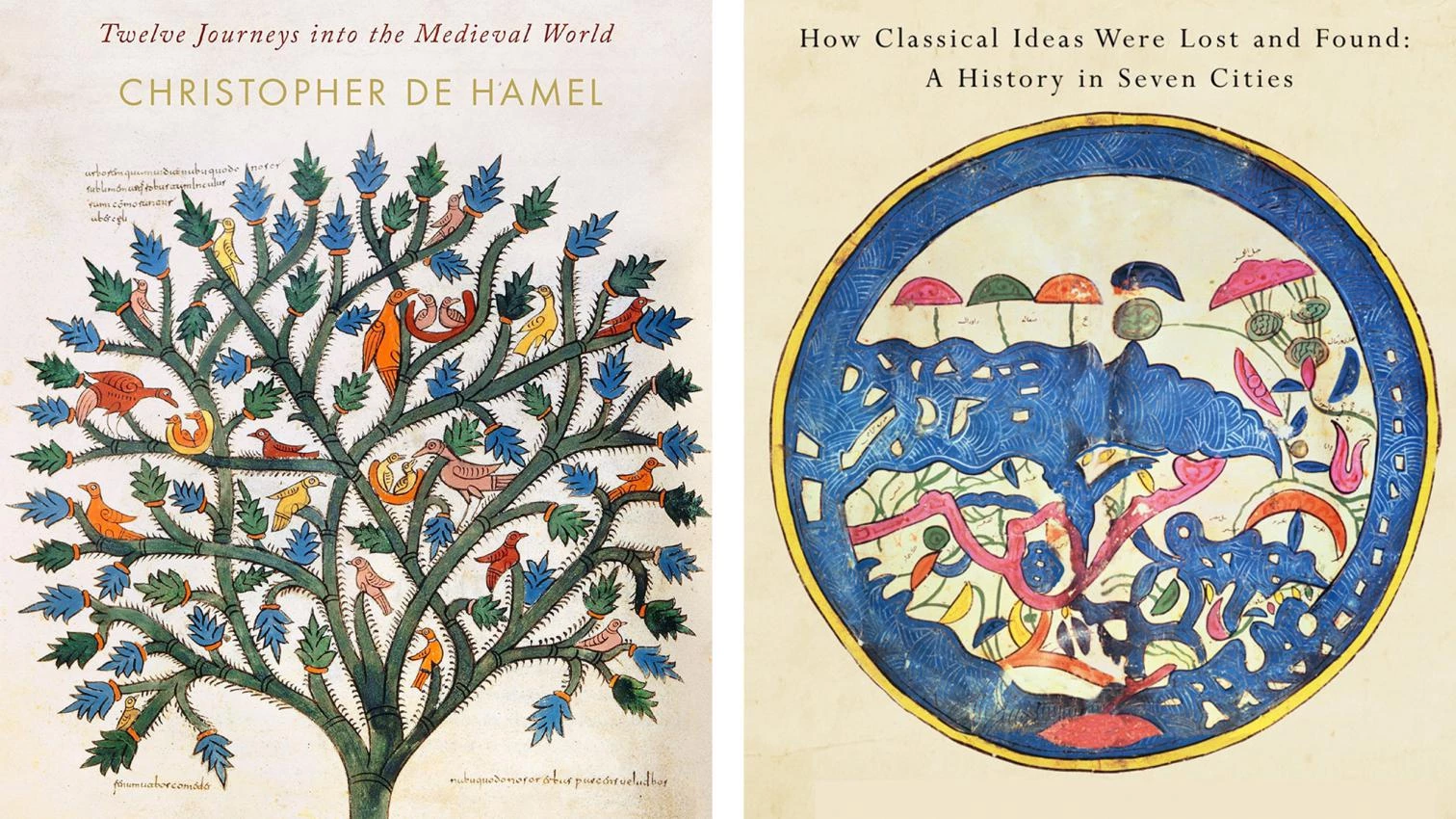

Christopher de Hamel was for a long time connected to the auction house Sotheby’s, and his erudite journey through codices – which go from the The Gospels of St. Augustine of the late 6th century to The Spinola Hours of the early 16th, and include gems like The Book of Kells, The Morgan Beatus, and The Hours of Jeanne of Navarre – is the fruit of his fascination with pieces of incalculable value, which he approaches with the same reverence and expectation one has when in the presence of a celebrity. The thorough information offered on each one is peppered with anecdotes and personal reminiscences, and the densely detailed narrative is made more enjoyable with literary descriptions of the institutions that harbor them and the people who orbit around them: a colossal achievement that manages to bring back the past these precious objects come from, presenting them to us with intimate gusto and historical passion.

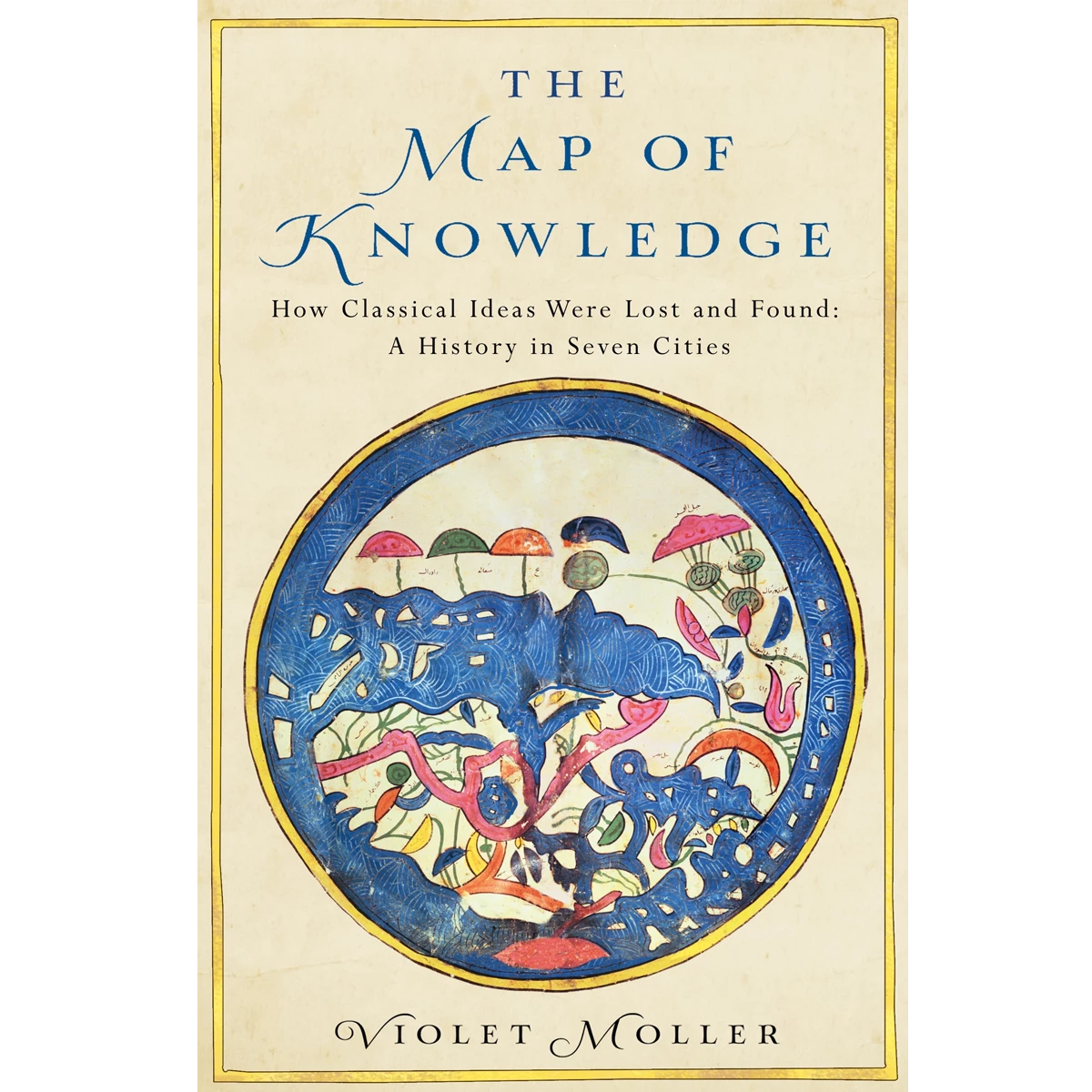

Violet Moller, for her part, does not deal with precious manuscripts, but rather with the codices that recorded the scientific knowledge of the ancient world, and centers on three of them: Euclid’s Elements, Ptolemy’s Almagest, and Galen’s collection of writings, which summarized classical mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, and would resurface during the Renaissance after a long series of translations and copies produced by scholars and scribes, many of them in the Islamic world. The historian establishes seven stations in this voyage, corresponding with the cities that became the cultural hubs at different moments along the way, from Alexandria in the 6th century to Venice in the 15th, where legendary presses turned manuscripts into printed books, passing through Baghdad, Córdoba, Toledo, Salerno, and Palermo, in an extraordinary periplus that throws light on our origins and reinforces our devotion to that marvelous invention that books are, handwritten at first, then printed to reach all, and the reports of whose death – paraphrasing Mark Twain – have been greatly exaggerated.