The Construction of the Disaster

The City of Culture and the Deportivo soccer stadium are two Galician projects by Peter Eisenman whose topographical traces express the spirit of the times.

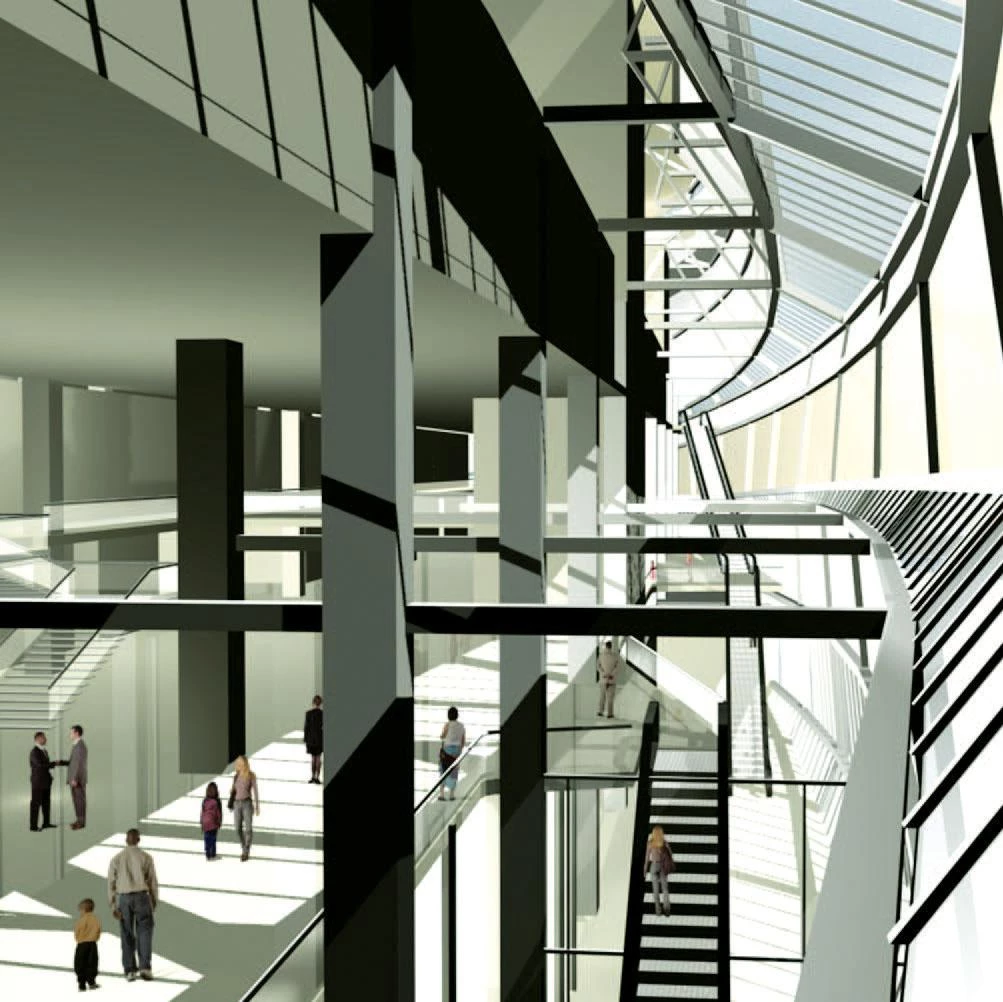

Don't say it was a dream. The bird’s eye view of the City of Culture of Galicia is a near-tactile testimony of ongoing construction, and yet the landscape molded by the moving of soil gives an oneiric impression. Set between the highway and the historic center of Santiago de Compostela, the vast territory carved by machines into folds and pleats spills at the edges like clay around a distracted potter, fluid and unexpected like mud after a downpour of rain, plastic and pulsatile like the melting mechanism of a surreal canvas. This organic geology of tongues and throats is to date the largest and grandest work of Peter Eisenman, a seventy-year-old architect who confronts his capolavoro with the impetuous imprudence of a seventeener. “Peter, it can’t get any better...” “Maybe we should leave it as is!” But the colossal piece of landart is only the frozen image of a work in progress, and the adventure of ongoing construction is summed up in the photograph shot.

The Monte de las Gaias, between the highway and the center of Santiago, is carved in folds to house the City of Culture of Galicia, a geological and organic project that is the most ambitious one by its author.

Winner of a competition held in 1999, Eisenman’s project is a compendium of the formal inter-ests that have nourished his architecture for the past three decades: the distorted grids of the syntactic seventies, the artificial excavations of the historicist eighties, and the blurred foldings of the fractured nineties. A computer fusion of the grooves of a scallop shell and the five streets of the city’s old quarter, the random geometry of the complex –meant to accommodate a mosaic of cultural uses, from an opera house and a history museum to a library and newspaper archive – frays into rueiros that melt in the smooth relief of the rural landscape. For some it will essentially be Galicia’s Guggenheim, a spectacular manifestation of the media power of contemporary architecture. For others it is more likely to be Manuel Fraga’s Escorial, a ti-tanic monument able to compete in stubborn per-manence with the great works of the past. And to most it will come across as a risky exploration of the disorder of the times, a visionary rehearsal of “the construction of the disaster.”

From Blanchot to Derrida

Eisenman frequently cites The Writing of the Disaster, one of the essential texts of the recently deceased Maurice Blanchot, and his architecture shows the same exigent fascination with denial, the same radical search for emptiness, the same delib-erate vertigo towards nothingness; but also the same penchant for paradox, word games, and abstruse formalism. His works go up in a physical world, but do not stay up without an elaborate scaffolding of texts and drawings: construction gets mixed up with writing, and each building becomes a book. The one on Santiago is entitled Code X, and this simultaneous reference to his tenth house, known as House X, and to the medieval manuscripts where the xacobeo myth originated reveals the architects’ liking for conceptive inventiveness and Baroque enigmas. The philosopher Jacques Derrida, with whom he had a long relation of collabora-tion and friendship, on some occasion wrote an essay entitled “Why Peter Eisenman Writes Such Good Books”, and it is easy to explain the tribute if we think of their shared passion for luminous intelligence and hermetic language: the ‘black light’ with which the critic Rafael Conte summarized Blanchot at the moment of farewell..

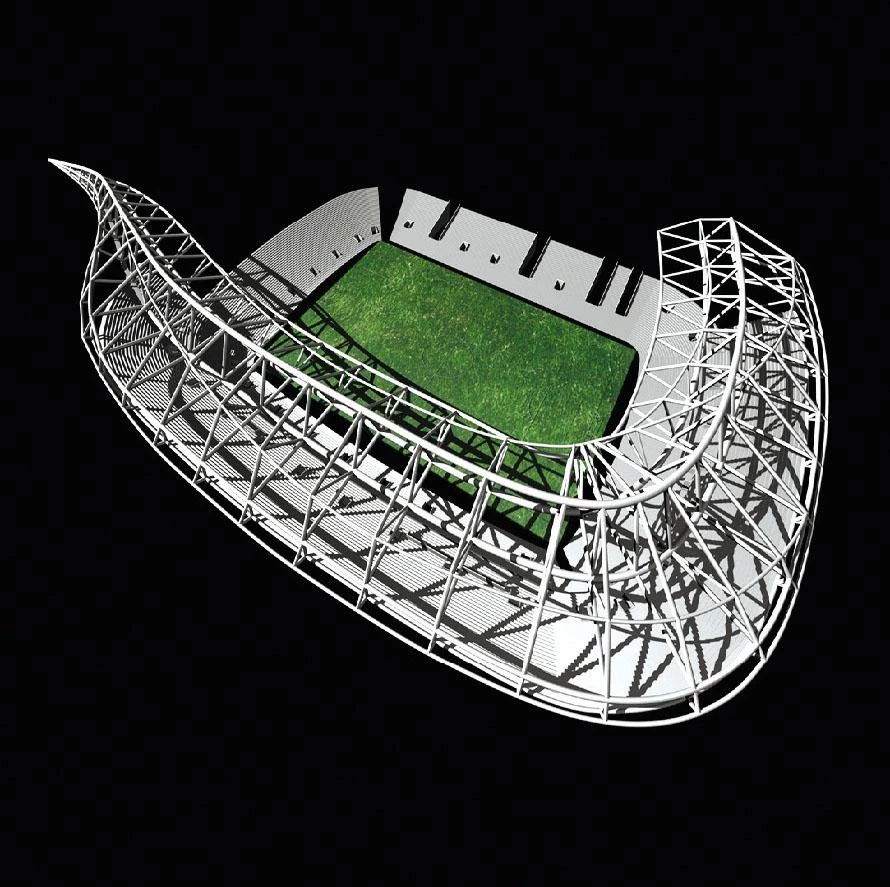

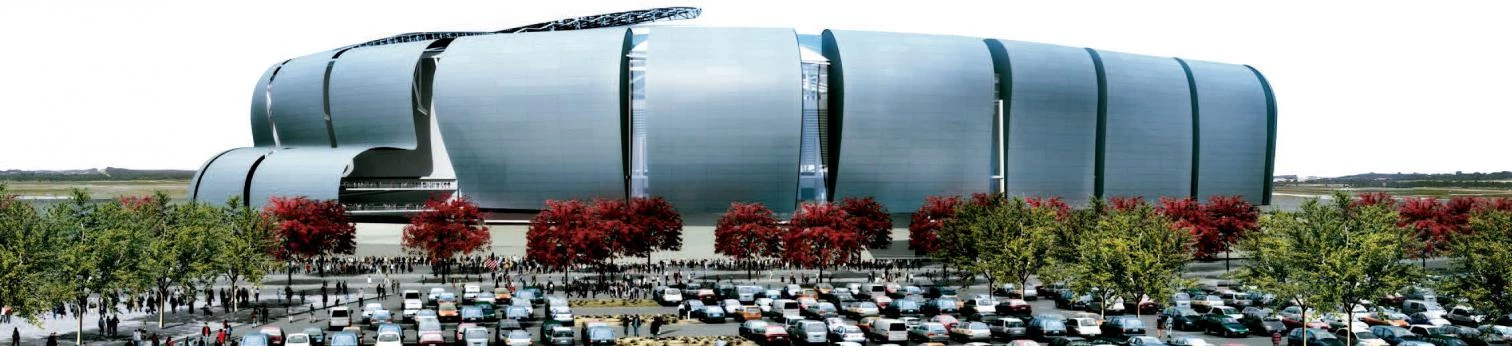

Los tentáculos fláccidos que amplían el estadio coruñés de Riazor (abajo) albergan viviendas, hotel y oficinas; y el caparazón estriado del diseñado en Glendale, Arizona, unifica usos deportivos y comerciales.

Now Peter the Obscure mentions the posthumous eulogy of Blanchot by Derrida, and in this final connection between his two favorite authors (triangulated at a distance by the huge figure of Emmanuel Lévinas) we perceive the tense lines that weave his intellectual mesh. To be sure, it seems extravagant to establish links between a faceless author who dedicated his life “to literature and the silence it demands”, and an architect of inevitable celebrity whose activities come with the noise and fury of the age of spectacle. But in Eisenman’s oxymoronic devotion to Blanchot beats the spiritual curiosity and the love of danger that has led him, a Jew of German origins who is building a Holocaust memorial in Berlin, to collaborate with Albert Speer, son of Hitler’s architect of the same name; or to nurture the friendship with Leon Krier, an architect of dia-metrically opposed style – who, by the way, contributed considerably to the critical rehabilitation of the senior Speer’s monumental classicism –, with whom Eisenman has exhibited recently at Yale University, and towards whose aesthetic extremism he is irrepressibly attracted. In the end, the scheme Eisenman likes to present seems plausible: if his generation was divided between Venturi and himself, and the following was split between Koolhaas and Krier, Koolhaas’ rediscovery of Venturi is duly balanced out by his encounter with Krier, in a new scheme of alignments whose fracture lines are no longer formal, but ideological.

But this Jacobine architect is now also a Jacobean, and as an honorary Galician he makes the construction of the City of Culture compatible with a major project in La Coruña, the remodeling of the Deportivo club’s stadium. In the preliminary proposal, the stadium stretches all the way to the beach with undulating tentacles containing a hotel, offices, shops, and apartments, blending the sport complex in with the urban fabric and rearranging the club’s services and image with an icon that ought to satisfy Depor president Augusto César Lendoiro and the city mayor Francisco Vázquez, two personalities known to be political and personal enemies. Mission impossible? Not for Eisenman, a football fan who follows closely the ups and down of the careers of players or the sways of fortune of the teams, and whose track record boasts already two other stadium projects: that of the Arizona Cardinals in Glendale, currently under construction, and the Olympic stadium of Leipzig, which in the wake of the German city’s recent designation as candidate for the Games of 2012 might see the moment of its building get closer.

Organic and expressionist like the City of Culture, the Deportivo de La Coruña project also belongs to the realm of dreams, but in these flaccid shapes flowing lazily toward the foamy water are a calmness and a voluptuousness that are more drowsy than dreamy, and its appendices resembling the arms of a giant squid embrace the city with a horizontal laxness that never quite form the night-marish profile of creatures of oceanic abysses. Both here and in Santiago, the agitation of disorder and the construction of disaster is more an exorcism than an exaltation: the Atlantic swell invades the city with a huge catastrophic wave, but this seismic tsunami solidifies into an amiable and protective eddy that shoos away the threat of convulsive times. Oil spillings and oil wars congeal and petrify in the threshold, and the viruses of pneumonia and intolerance stop short in the metaphoric mask of arrested movement. But don’t say it was a dream.