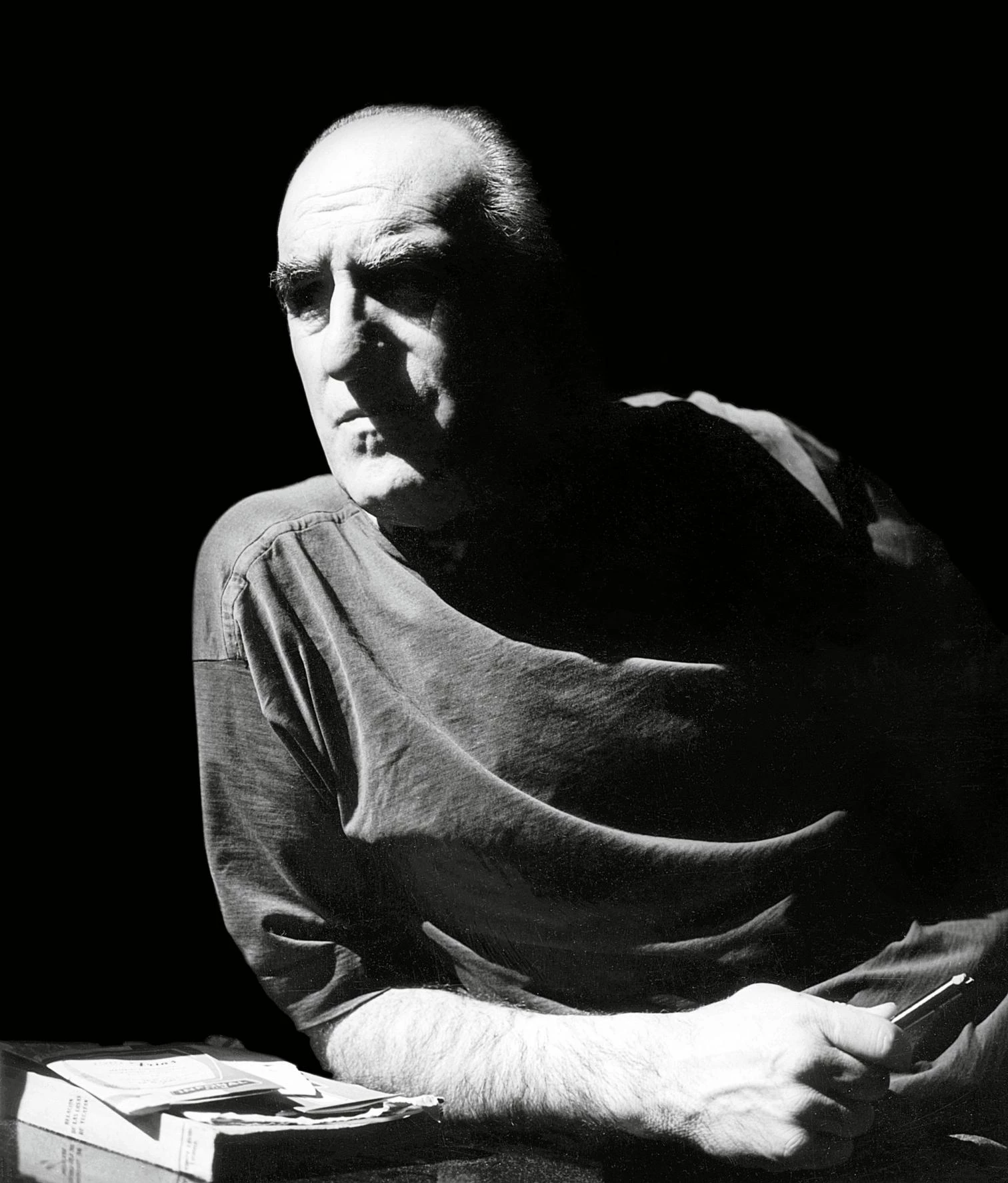

Joaquín Vaquero Palacios (1990-1998), an architect who also painted, besides other parallel activities, belongs to that heroic lineage of ‘total creators’ that is so hard to categorize in official historiographies. More so in a country like Spain, prone to simplifying hybrid professional careers and biographical driftings as iconoclastic as those of Vaquero, who does not easily fit into the already long list of Spanish ‘modern masters,’ nor into the official lineage linked to the eminently abstract tradition of 20th-century artists. In both genealogies, Vaquero’s long life has traditionally been seen as picturesque and peripheral, in the course of which the architect has gone through convulsive changes, without ever ceasing to look out from the watchtower of ‘great art,’ in a comprehensive and perhaps nostalgic view of certain creative omnipotence that no longer tallied with the inevitable turn towards the specialization of disciplines that was a sign of the times.

In the context of giving attention to more boundary figures and of critically reconsidering the always controversial relationship between art and engineering, between which architecture positions itself, the ICO Museum in Madrid presents ‘Joaquín Vaquero Palacios: The Beauty of the Huge,’ an exhibition that from the start marks the coordinates of the monumental, sublime nature of Vaquero’s work, and its consideration as an aesthetic rationale capable of appealing as much to the senses and to cultural truths as to the industrial and scientific function of power plants in his native Asturias, the chapter of his oeuvre which the show focuses on.

Curated by Joaquín Vaquero Ibáñez, the architect’s grandson, reducing the exhibition to this set of infrastructural works – all of them commissioned to Vaquero by the company Hidroeléctrica del Cantábrico, one of whose proprietors was the architect’s father – has made it easier to polish the show’s storyline. By leaving out the evident lure of the initial rationalist phase of Vaquero’s work, or the brilliance of his historicist stage, epitomized in masterworks as little known as the Marketplace of Santiago de Compostela, perhaps it is the infrastructural nature of the plants at Salime, Miranda, Proaza, Aboño, and Tanes that best reflects the multidimensional realities (artistic, cultural, landscaping, and energy) that overlap in the work of Vaquero. A syncretic work capable of simultaneously inhabiting both the more concrete and technical and the more allegorical and subjective dimensions of architecture.

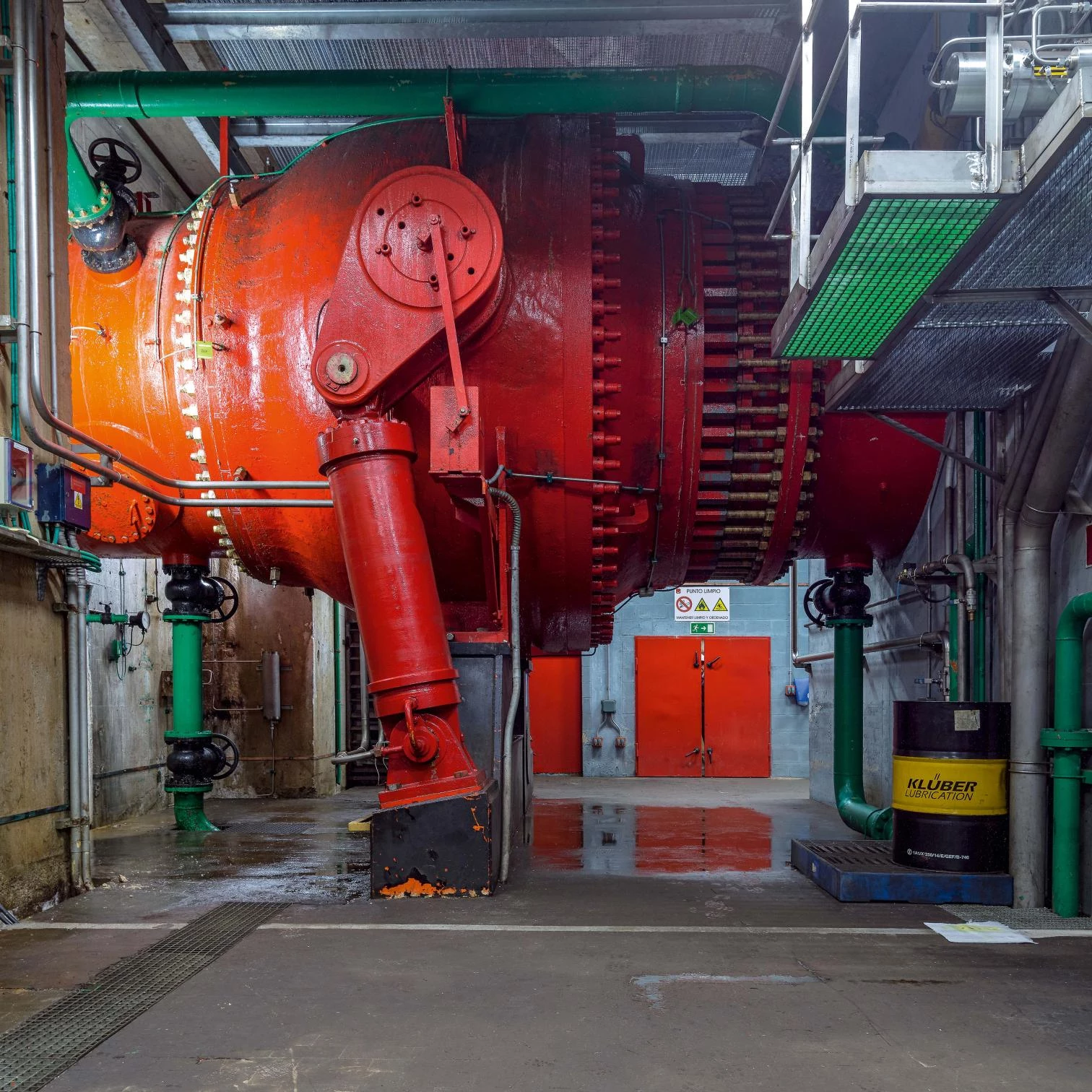

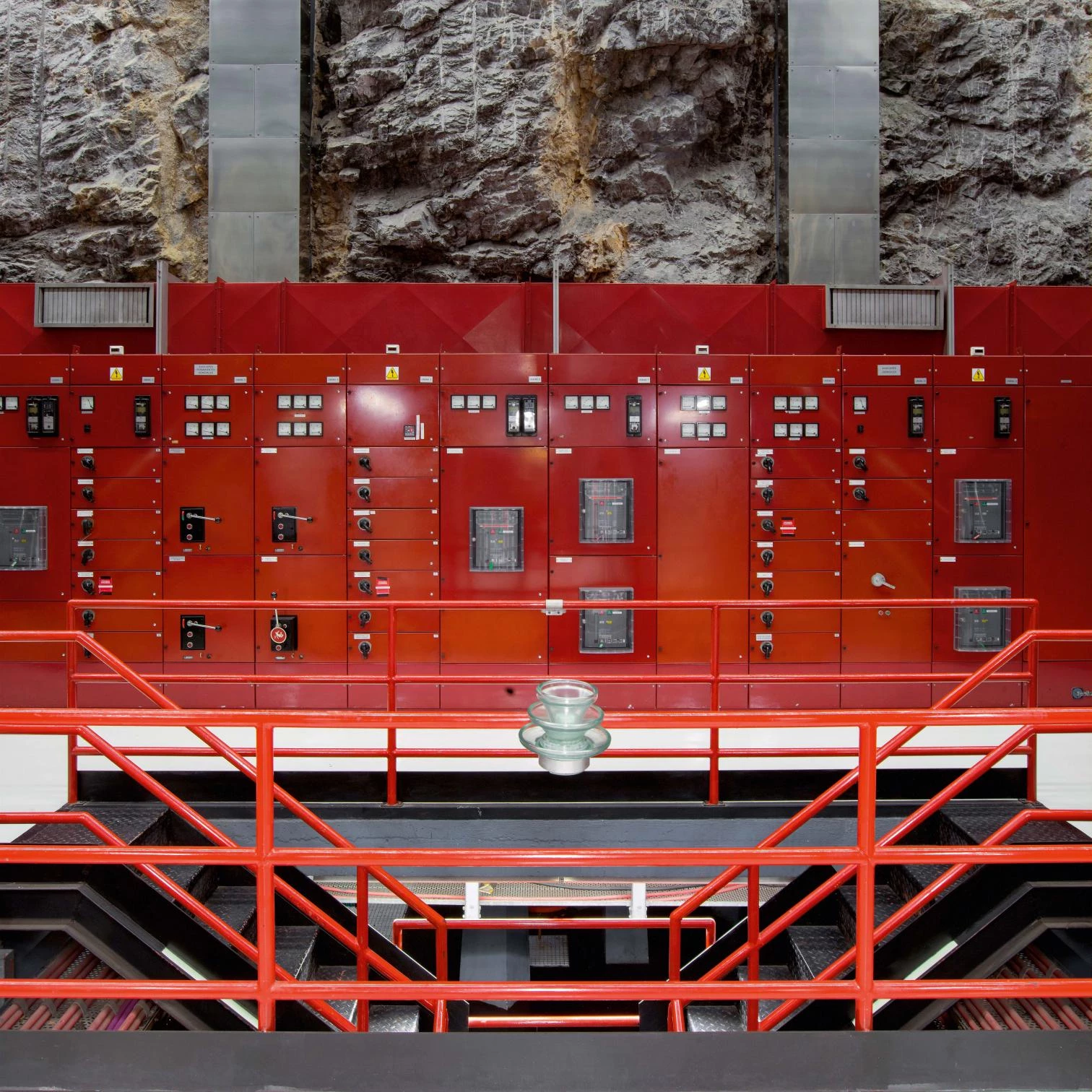

The design of the exhibition, carried out by Vaquero Ibáñez himself, in collaboration with Marina Villalobos, achieves the difficult objective of conveying the visual and material exuberance of these constructions to a wider public, thanks mainly to the extensive series of photographs by Luis Asín, who spent a year shooting the power plants the way they are now, after sixty years of intensive use. Photographs which, in their chromatic power and in the evidence of the amiable wearing out of concretes and steels, strike a contrast with the schematics of the original technical documentation on display: simple technical plans demonstrating that only by taking in the allegorical iconography applied to the architecture and the sculptural perception of the finished works can we fully understand these titanic works.

Expressions of Energy

Added to Asin’s photographs and the collection of original documents are efficient chronological explanations to situate the subjects in their historical moments. Of interest in this regard is Vaquero’s stint as deputy director, then director, of the Spanish Academy of Fine Arts in Rome (1950-60). This put him in touch with some of the leading architects and artists of the time, such as Le Corbusier, Aalto, Dalí, and Picasso, and paved the way for him to take on the restoration and renovation of the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, still in use today. In addition, the exhibition includes reproductions of furniture elements and graphic designs like the Hidroeléctrica del Cantábrico logo, and an amazing scale model of the power plant in Proaza, executed in reinforced concrete.

Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog of the same title, a brilliant complement which, along with reproductions of Luis Asín’s images, features texts by Iñaki Ábalos, Francisco Egaña, Rafael Moneo, Juan Navarro Baldeweg, and Natalia Tielve, all in a painstaking edition published by This Side Up. That the work of Vaquero Palacios merits a rereading is illustrated by the revision carried out as much in these texts and as in the actual design of the book and the way it engages with the photographs, some of which, because of the futuristic look of the power plant interiors, could easily be mistaken for the retro-oneiric inclinations of the Instagram generation.

This capacity of Vaquero’s work to make leaps in time – and to update itself through representations made with contemporary sensitivities – renders it easier to understand and brings it closer to wide audiences of today. Such closeness can be attributed to the fact that the constructions themselves seek to explain – and make visible in an understandable way – the processes that lie latent in the generation of energy, through the allegorical and narrative nature of their iconography.

In the foreword to the exhibition catalog, Joaquín Vaquero Ibáñez recalls a particular anecdote that says much about the crossroads between abstraction and figuration in which the career of Vaquero Palacios places itself. He describes the moment when his son, Joaquín Baquero Turcios, artist and collaborator of his in some works, discovered the need – while they were working together on the huge mural inside the power plant at Salime – to adopt a realistic language in order to increase the work’s capacity to convey something to the viewer: “The first sketches were abstract, but once I became aware of the human effort and the constructional epic involved, the abstract began to lose out to the narrative of the feat.”

Jacobo García-Germán teaches at ETSAM-UPM and has published Estrategias operativas en arquitectura.