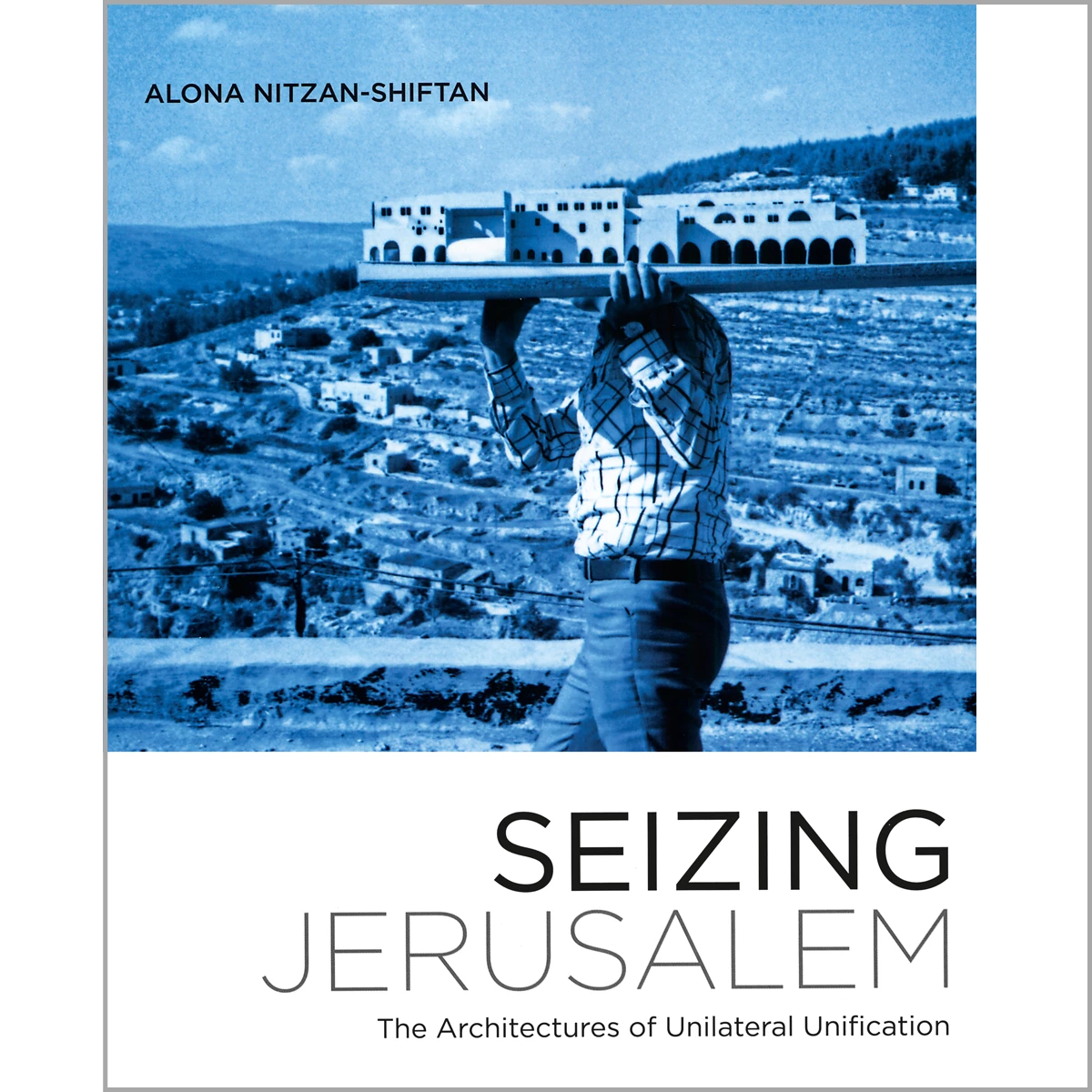

The Six-Day War began a new chapter in the troubled history of the Middle East, a shaken geography whose fractures extend far from its epicenters. On 7 June 1967 the Israeli army seized East Jerusalem, paving the way for a ‘unilateral unification’ of the city, as called by Alona Nitzan-Shiftan, the Technion professor who has admirably documented the architectural history of the first decade of this process. And in December 2001 the Taliban surrendered in Kandahar, and the country started a reconstruction where the Aga Khan Development Network played a major role. now presented in a splendid book.

The political use of architecture and urbanism in Jerusalem had in the early period of unification a cultural dimension that resonated with the crisis of architectural modernity. The Israeli professor painstakingly analyzes the relationship between architectural and political modernity, and compares three visions of democracy that would take center stage in succession: the communitarian vision of sabra (Israel-born) architects, who with a combination of brutalism and regionalism (a neo-orientalism based on the Palestine vernacular) wanted to bring back the spirit of the place to establish a shared cultural identity; the liberal vision expressed by the charismatic Mayor Teddy Kollek, who considered Jerusalem a ‘sacred city of mankind’ and preferred to protect the existing mosaic of religious and ethnic identities; and the universal vision defended by many international consultants summoned to intervene in the city, from Louis Kahn or Buckminster Fuller to Lewis Mumford, who wanted to defeat nationalism through their proposals. A fascinating story that ends on a melancholy note, accepting the inevitability of social antagonisms and the idea that “the genius loci of Jerusalem lies not only in its topography and sanctity, but in its divisions and borders and oppression.”

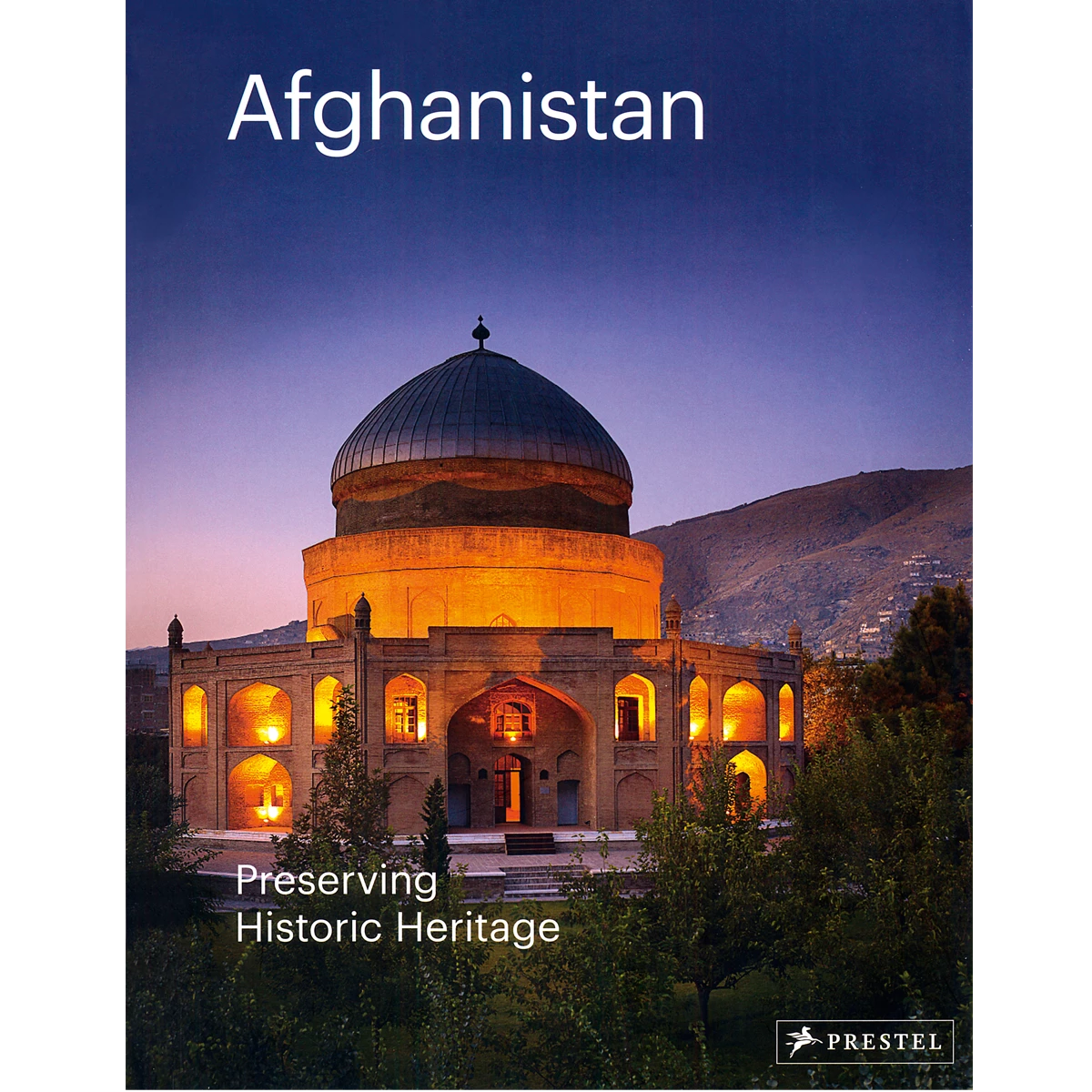

In contrast with this variety of intentions, the spirit of the Aga Khan’s interventions in Afghanistan lies in using architecture as a tool for defining a contemporary identity for the country, and with this purpose it has channeled over a billion dollars into the protection and refurbishment of its historical heritage in Kabul, Herat, Balkh, and Badakhsgan; a project involving more than 120 monuments, all presented here with excellent photographs and elegant floor plans and sections that offer a dazzling portrait of the architectural heritage of Afghanistan: a historical legacy of cities, buildings, and gardens which the conflict has not managed to erase, and which attests to the plurality of cultures, civilizations, and empires that converged in this crossroads of antiquity.

Jerusalem and Afghanistan: two architectures traumatized by wars and raised on a millenary, plural past.