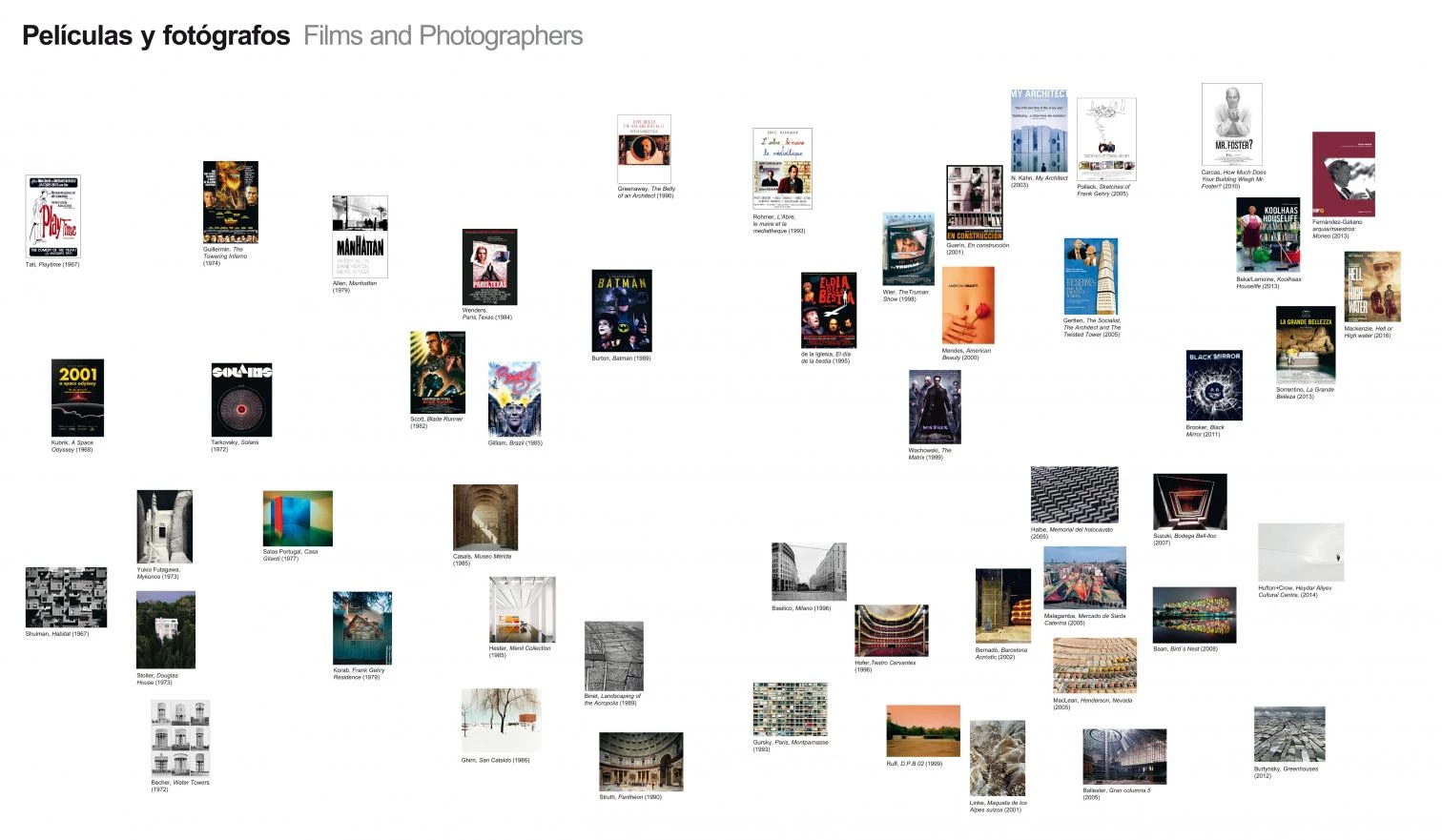

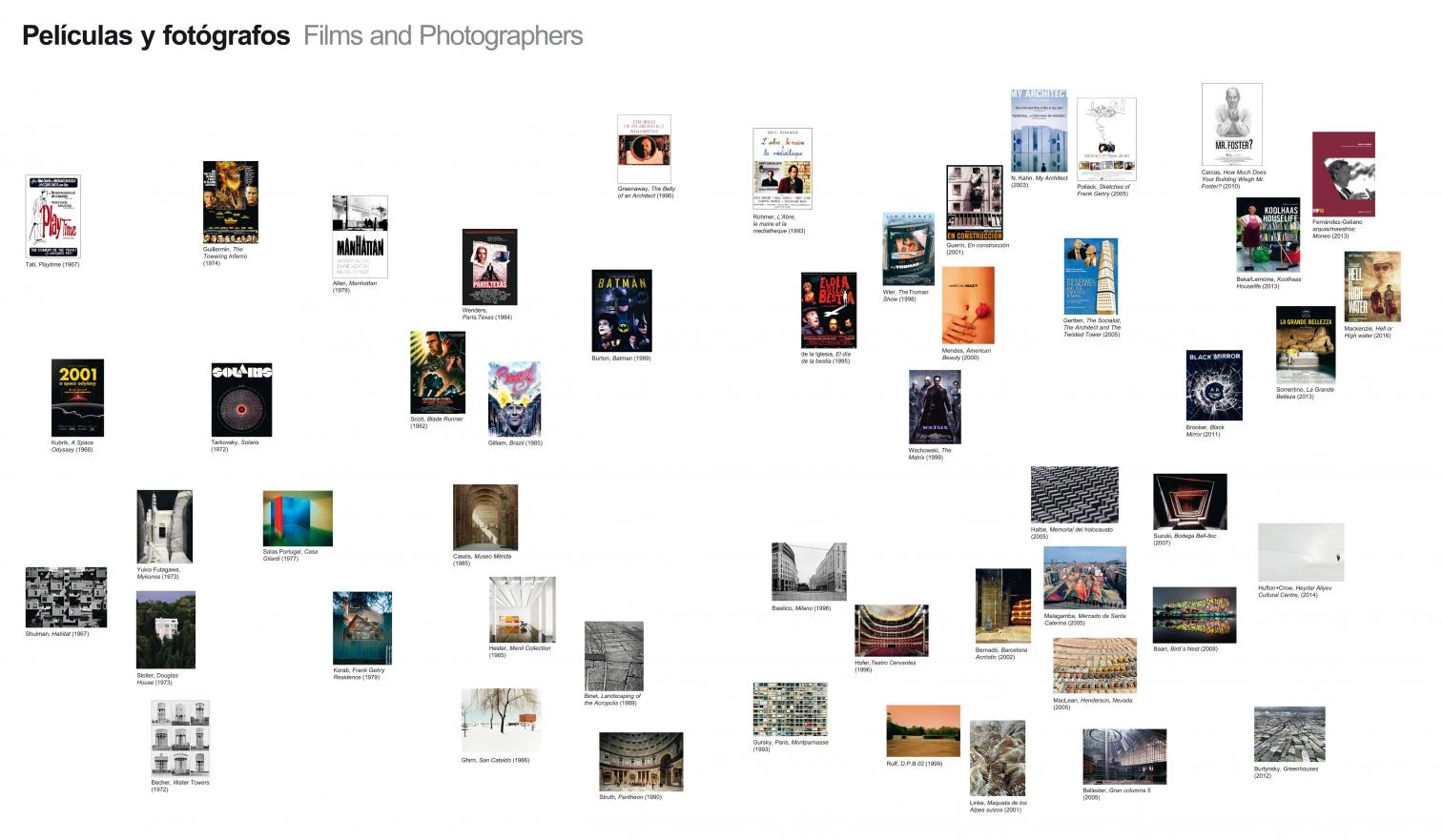

Films and Photographers, Dystopian Visions

The Eye of the Camera

The greedy eye of the architect feeds on images. ‘Je n’existe dans la vie q’à condition de voir,’ said Le Corbusier, and this visual avarice finds its best supply of nutrients in photography and cinema. The master, who sometimes presented his projects as cinematographic storyboards, and who carefully supervised photography of his works, had Lucién Hervé as favorite portrayer, and in this he was no different from so many other architects who cultivated a fertile symbiosis with their photographers. But photography inseminates architecture beyond its mere representative function, as does cinema, which besides depicting buildings and cities has inspired architects with its framings, its camera movements, and its montage techniques. Modern architecture and cinema were born at the same time, and the close relationship between them goes way beyond architectures of film sets contaminating permanent constructions.

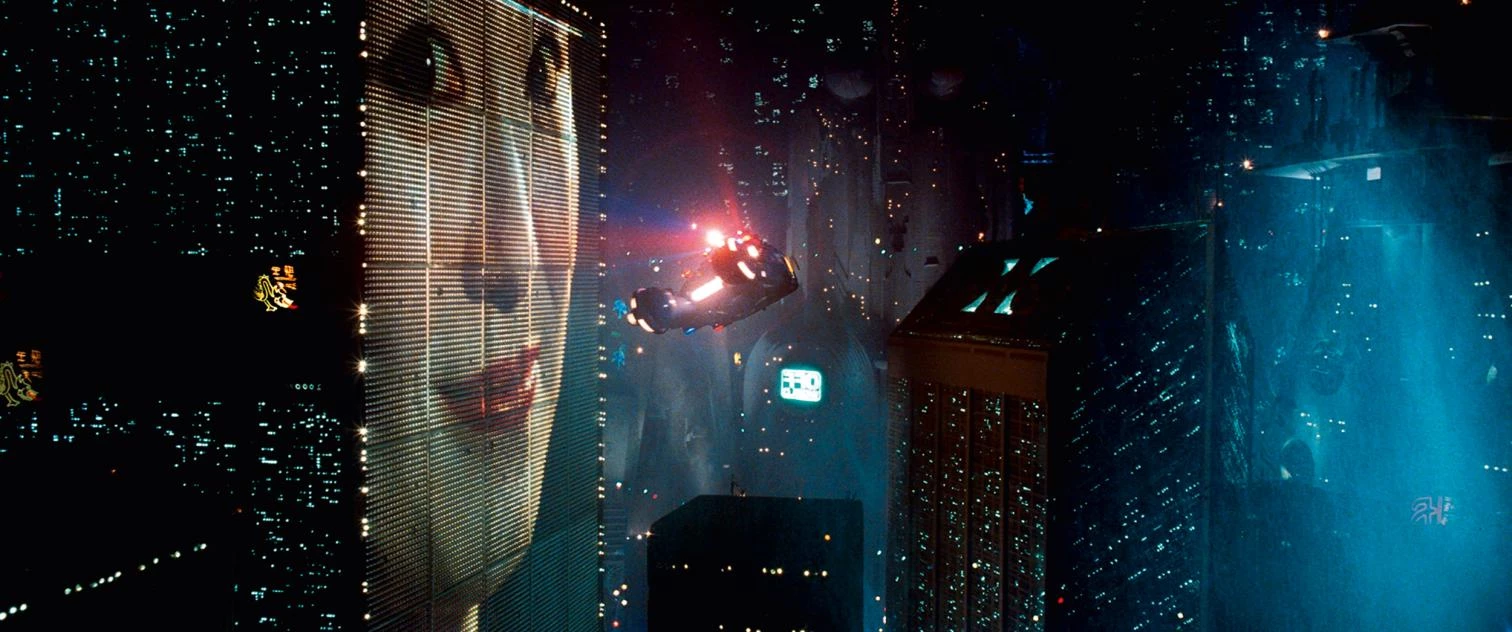

We do not know whether modern architecture ended in 1972 with the blowing up of the Pruitt-Igoe blocks, as Charles Jencks says, or in 1966, when Rossi and Venturi questioned its postulates. I dare to suggest other dates: modern architecture perished in 1958, when Jacques Tati premiered Mon Oncle, and modern urbanism in 1967, when he premiered Playtime. No one has put modern vacuity into question more intelligently and elegantly, and it took some time for Eric Rohmer’s delicious L’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque or Aki Kaurismäki’s moving films to offer comparable tales, where the ridiculous always preserves the dignity of characters. If modernity was an artistic and social utopia, its fruits effortlessly step from the caricature to the ominous. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the foreshadowings of the future promised by technology are often dystopian: from Kubrick and Arthur Clarke’s 2001 to Ridley Scott and Philip K. Dick’s Blade Runner through Tarkovski and Stanislaw Lem’s dazzling Solaris, the poetry and visual imagination of filmmakers and writers embellish worlds of ominous darkness.

Films like Blade Runner or Playtime harbor a powerful critique of the modern city.

Occasionally, the menacing cruelty of the future finds resonance with the architectural environments where filming takes place. When Stanley Kubrick was bringing Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange to the screen, he looked for locations in architecture magazines, and this led him to use the interiors of ‘Skybreak,’ the house designed by Foster and Rogers’ Team 4; and when Terry Gillian drew inspiration from Orwell’s 1984 to film Brazil, it was Ricardo Bofill’s Les Espaces d’Abraxas that with their labyrinthine complexity evoked an inhuman environment. Gotham City, always somber, can be described with the visual sophistication of Tim Burton’s Batman or Beatty’s Dick Tracy, but the contemporary metropolis is portrayed with the nocturnal desolation of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver more frequently than with the daytime cheer of Woody Allen’s Manhattan; and skyscrapers, once scenes of technological and artistic achievement, are now either protagonists of catastrophes, as in The Towering Inferno, or diabolical sets, like Johnson and Burgee’s leaning towers in El día de la bestia, apocalyptic images a far cry from the confidence in the individual and the future that the architect unforgettably played by Gary Cooper in King Vidor and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead conveyed.

But cinema has not only engaged in dialogue with architecture through the sinister science fiction of movies like Matrix; it has also interacted with it through the melancholy exaltation of classicism and the great works of the past, as in Greenaway’s The Belly of an Architect or in Sorrentino’s La Grande Bellezza, which shows a decadent and fascinating Rome; through the caustic portrayal of sugary suburbia in Sam Mendes’s American Beauty or Peter Weir’s The Truman Show, which explores the blurred limits between reality and fiction in Seaside, the model city of America’s new urbanists; or through the desolate landscapes of Wenders’s Paris, Texas or Sayles’s Lone Star, filmed in the same territory that has been used to show with extraordinary dramatic force the effects of the real estate crisis provoked by subprime mortgages, in Hell or High Water, the movie by the director David MacKenzie and the screenwriter Taylor Sheridan which reflects – even more than the insiders’ views of the economic world, in the manner of The Big Short – the social devastation and human suffering caused by the financial crisis.

With these films, cinema comes close to being a documentary portrait of our times, and this has also been the intention of filmmakers like José Luis Guerín with Work in Progress, where people’s lives get tangled up with the physical transformation of a working-class neighborhood of Barcelona, showing an empathy and critical spirit not always present in architecture documentaries, let alone those that with heroic accents narrate the materialization of great contemporary constructions. But My Architect treats Louis Kahn with filial fondness, Sydney Pollack traced his Sketches of Frank Gehry from the friendship that united them, Norberto López Amado and Carlos Carcas portrayed an at once titanic and intimate Norman Foster, and the arquia/maestros series leaves testimonies of great living architects through their own words. More caustic are Fredrik Gertten’s etching of Santiago Calatrava, The Socialist, the Architect and the Twisted Tower or Bêka and Lemoine’s Koolhaas Houselife, one of the sixteen documentaries produced by the pair with a shared transgressive determination that aspires to demystify the mythical works and authors of contemporary architecture.

Very different is the case of photography, which in many instances is closely linked to the task of disseminating works, and thus tries to present them in the best possible light; this circumstance in no way diminishes their artistic worth, and rapport between architect and photographer can come to be so close as to form an indissoluble creative amalgam. Take the cases of mythical photographers like Julius Shulman, Ezra Stoller, or Balthazar Korab, a tradition which continues today with Paul Hester, Roland Halbe, or Duccio Malagamba. And if we cannot imagine Le Corbusier without Lucien Hervé, neither can we separate the work of Barragán from the photography of Armando Salas Portugal or the architectures of Spain’s transition to democracy from the images taken by Lluís Casals, just as early Catalan modernity is inextricably bound to Catalá-Roca. Not to mention the photographers associated with publishing endeavors, such as Yukio Futagawa with GA or Hisao Suzuki with El Croquis. In the final analysis, the boundaries between commercial and artistic are blurry, and photographers like the brilliant Iwan Baan effortlessly straddle the line between commissions and personal pursuits.

Of course there are also photographers who from the start try to find a clear niche for themselves in the panorama of contemporary art, understanding their work as such. In this terrain one is hard put to find a group more compact, more keen on the physical environment, and more influential in architecture than those trained in Düsseldorf with Bernd and Hilla Becher, two masters of documentary photography whose black-and-white series of industrial architectures are iconic of our times, and who conveyed to their pupils a topographic fascination for landscapes, cities, and buildings, represented with exquisite skill on a grand scale, to the point of taking on pictorial qualities. The list of disciples of theirs is truly impressive. The mere sound of their names suffices to give an idea of their influence: the likes of Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Struth, and Axel Hütte would each require a chapter of their own, and if we recall that the same Kunstakademie produced artists like Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, and Thomas Demand, it is once again clear that art hatches when it takes on critical mass in a place and time.

Besides these formidable concentrations of energy, which with their glow enlighten the times we are living, there are other more dispersed beams of light that teach us to look at the planet through their photographs. Hence we have the Canadian Edward Burtynsky, whose industrial landscapes give us an ecological conscience through his at once critical and refined lens; the American Alex MacLean, architect and pilot, who with his aerial images has taught us about the impact of urbanization on the territory; the Italian Gabriele Basilico, who has documented the urban landscapes of today, from Europe’s harbors to desolate peripheries; the Catalan Jordi Bernadó, who with an ironic view has narrated the transformation of cities; and the Madrid artist José Manuel Ballester, who stepped from painting to photography to interpret architectural spaces with exceptional skill and admirable subtlety. Through their images all these photographers show that ‘the camera also builds,’ and without them architecture would lose their presence in the media networks that string the world together and inextricably involve us in a global conversation.

1967-2017

Fifty Films and Photographers

Jacques Tati, Playtime (1967)

Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Andréi Tarkovsky, Solaris (1972)

John Guillermin, The Towering Inferno (1974)

Woody Allen, Manhattan (1979)

Ridley Scott, Blade Runner (1982)

Wim Wenders, Paris, Texas (1984)

Terry Gilliam, Brazil (1985)

Tim Burton, Batman (1989)

Peter Greenaway, The Belly of an Architect (1990)

Eric Rohmer, L’arbre, le maire et la médiathèque (1993)

Álex de la Iglesia, El día de la bestia (1995)

Peter Weir, The Truman Show (1998)

Lana Wachowski, Lilly Wachowski, The Matrix (1999)

Sam Mendes, American Beauty (2000)

José Luis Guerín, En construcción (2001)

Nathaniel Kahn, My Architect (2003)

Fredrick Gertten, The Socialist, the Architect and the Twisted Tower (2005)

Sydney Pollack, Sketches of Frank Gehry (2005)

Carcas, L. Amado, How Much Does Your Building Weigh, Mr. Foster? (2010)

Charlie Brooker, Black Mirror (2011)

Ila Bêka, Louise Lemoine, Koolhaas Houselife (2013)

Luis Fernández-Galiano, arquia/maestros: Rafael Moneo (2013)

Paolo Sorrentino, La Grande Bellezza (2013)

David Mackenzie, Hell or High Water (2016)

Julius Shulman, Habitat (1967)

Bernd & Hilla Becher, Water Towers (1972)

Ezra Stoller, Douglas House (1973)

Yukio Futagawa, Mykonos (1973)

Armando Salas Portugal, Casa Gilardi (1977)

Balthazar Korab, Frank Gehry Residence (1979)

Lluís Casals, Museo Romano de Mérida (1985)

Luighi Ghirri, San Cataldo (1986)

Paul Hester, Menil Collection (1985)

Hélène Binet, Landscaping of the Acropolis (1989)

Thomas Struth, Pantheon (1990)

Andreas Gursky, Paris, Montparnasse (1993)

Gabriele Basilico, Milano (1996)

Candida Höfer, Teatro Cervantes (1996)

Thomas Ruff, D.P.B. 02 (1999)

Armin Linke, Maqueta de los Alpes suizos (2001)

Jordi Bernadó, Barcelona Acròstic (2002)

Roland Halbe, Memorial del Holocausto (2005)

Duccio Malagamba, Mercado de Santa Caterina (2005)

Alex MacLean, Henderson, Nevada (2005)

José Manuel Ballester, Gran columna 5 (2005)

Hisao Suzuki, Bodegas Bell-lloc (2007)

Iwan Baan, Estadio olímpico de Pekín (2008)

Edward Burtynsky, Greenhouses (2012)

Hufton+Crow, Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center (2014)