The Enemy’s House

On the third anniversary of 9-11, the recreation of Bin Laden’s house in the Tate Gallery contrasts with the exhibition on skyscrapers in the MoMA.

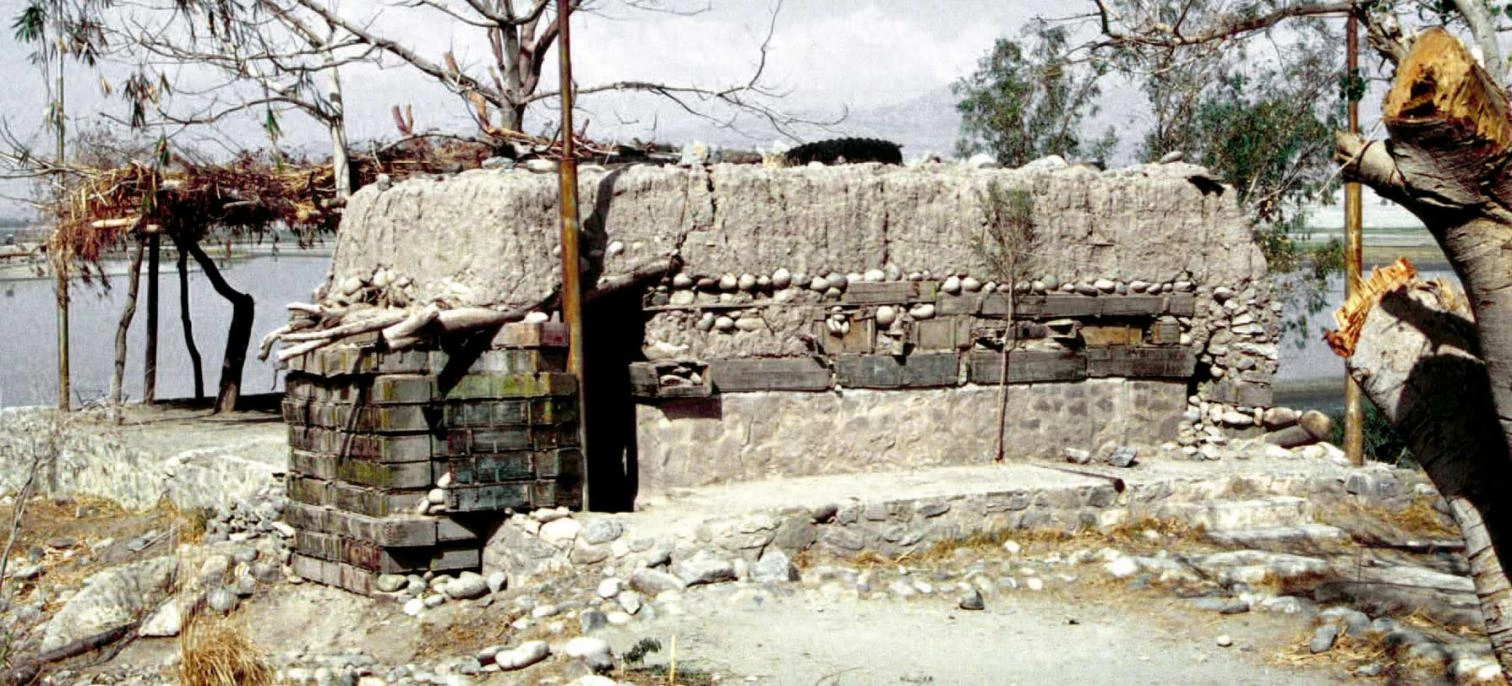

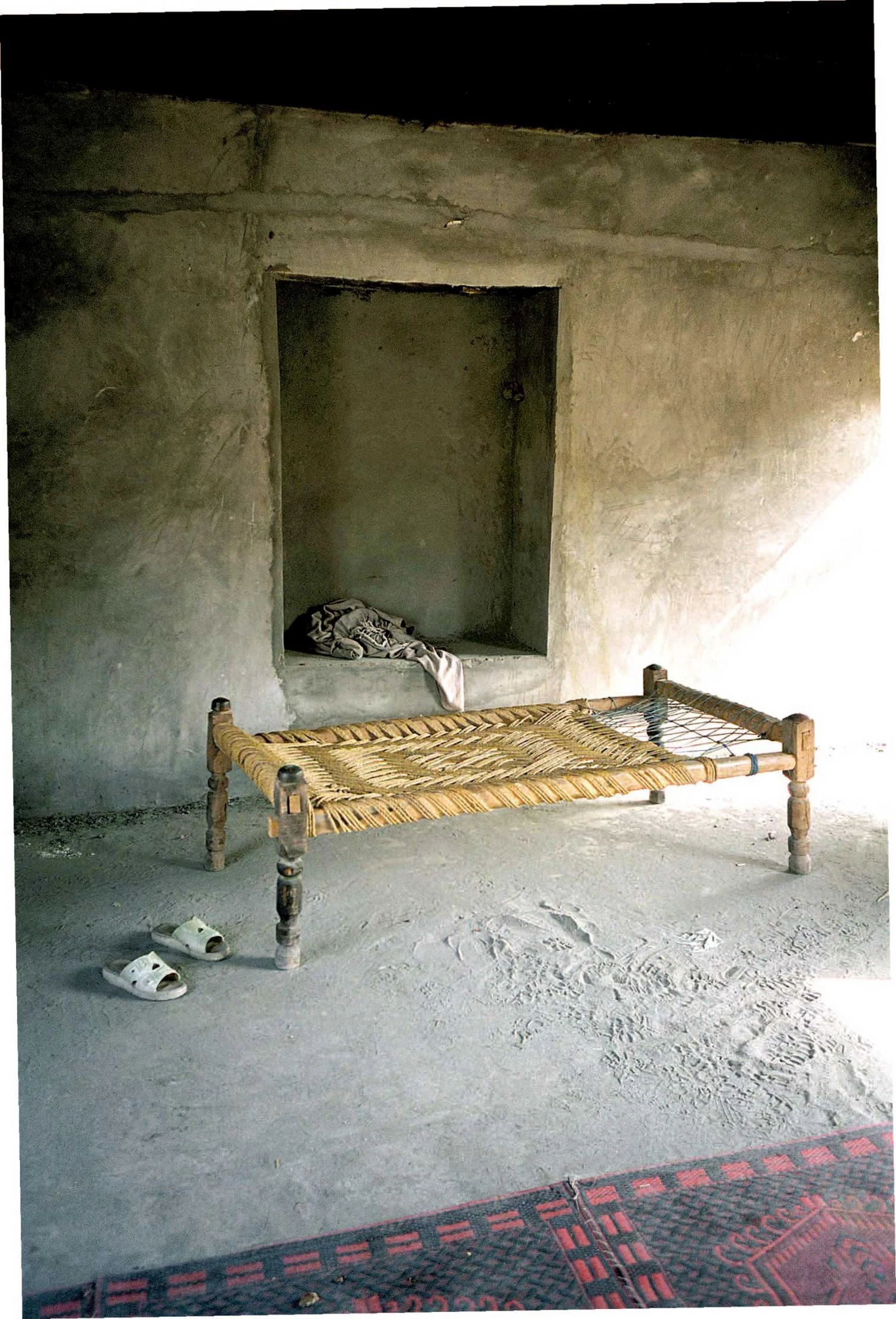

Osama Bin Laden’s house is the cell of an ascetic. Reconstructed by the British artists Ben Langlands and Nikki Bell as an interactive digital model – after documenting the latest known dwelling of Al Qaeda’s leader with photographs and videos – the hut of stone, adobe, brick, and wood is a shelter of penitential purity that extends its pòvero laconicism to the humble canopy of branches that shades the terrace over the river: an uninhabited bunker, but also an oneiric refuge of elemental architecture whose minimalist purity, worthy of the likes of John Pawson or Peter Zumthor, perhaps owes as much to the retina of the authors as to the stripped elegance of the warrior and spiritual leader. Tom Ford praised the impeccable style of Hamid Karzai, imposed as Afghanistan’s president after the war, when dressed with the karakul sheep’s fur and the cape of green silk that express the country’s ethnic diversity, but the syncretic outfit of the politician cannot compete with the effortless refinement of the Arab terrorist, who appears on the screens of Al Jazeera arrogant and beautiful like Mohammed, and with the same serene perfection that characterizes his house, the recreation of which, carried out by the London partners for the Imperial War Museum, is on display in the Tate Gallery starting 20 October, in its capacity as finalist of the Turner Prize.

The domestic asceticism of those who have used terror against western society is manifest in the recreation carried out by Langlands and Bell of Bin Laden’s Afghan home, the last known shelter of the leader of Al Qaeda.

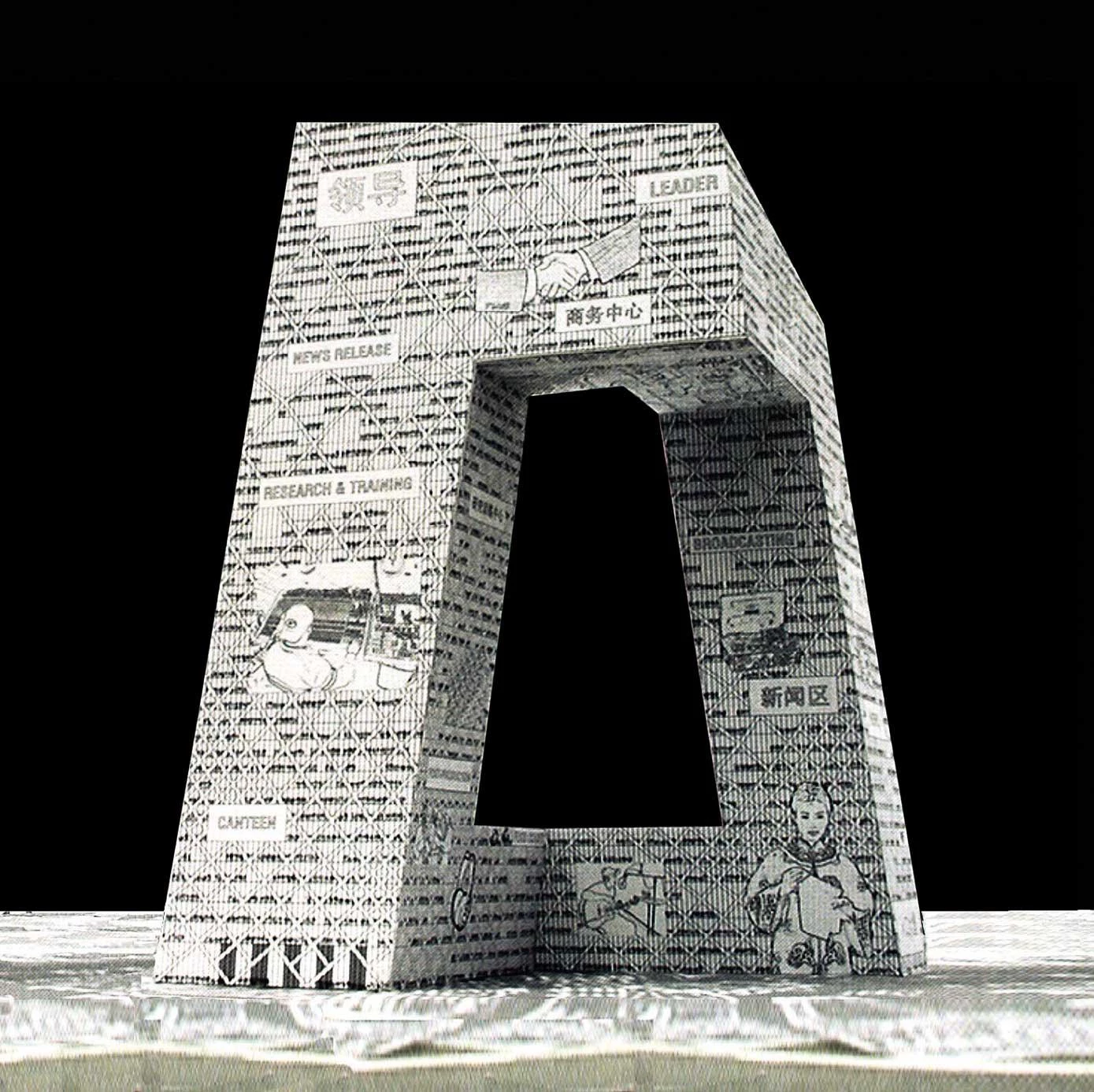

In contrast to the silent retreat of the intellectual author of September 11, the third anniversary of the tragedy coincides, in New York, with the boastful echoes of a Republican convention that reaffirms the macho vigor of a war presidency, and with the last weeks of an exhibition that through the aesthetics of titanism has enabled the Museum of Modern Art to dispel the shadows that the destruction of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers threw on high-rise construction. Visitable in MoMA-Queens until 27 September, this exhibition-exorcism presents 25 works and projects of the past decade, selected by the museum’s architecture curator Terence Riley and the engineer Guy Nordenson on the grounds of the technical, urbanistic, and programmatic innovations they put forward, and the result is an unorthodox panorama that reflects both the material capacity and the spiritual confusion of the west, both its physical power and its intellectual impotence. Hardly absolved by precision projects like Norman Foster’s – the ballistic Swiss Re tower in London and the Brancusi/Noguchi mix of the Brit’s entry to the WTC competition – nor by provocative proposals like the loops of Peter Eisenman and Rem Koolhaas – the unexecuted Max Reinhardt Haus in Berlin and the CCTV headquarters in Beijing whose execution is still in question –, the MoMA selection testifies to the poor architectural quality of the majority of the symbols of our industrial society’s technical and economic muscle.

The spectacular futurism of the great buildings raised by contemporary technology – from Norman Foster’s Swiss Re to his own proposal for Ground Zero – is a counterpoint to the austerity of the enemies of western values.

The uneven contest between the hut and the skyscraper arouses conflicting sentiments. On one hand, Bin Laden’s primordial house recalls that of other anti-modern terrorists. A case in point is the very famous Unabomber that Richard Barnes’s dramatic photographs gave a mythical aura to, a cottage in the Montana woods that was transferred to a San Francisco warehouse to serve as proof of derangement of the individual on trial for sending explosive parcels to engineers and scientists. It was not far removed from the modest accommodations (described in detail in the U.S. Congress report on the 9-11 attacks) of the members of the squad of Mohammed Atta, an architect and urban planner who was preparing a doctoral thesis on vernacular Islamic construction before he piloted a Boeing into a Manhattan skyscraper. To be sure, the same Adolf Hitler who loved academic architecture lived the bohemian life of a self-taught student, urban draftsman and persistent music lover before initiating the long march toward the German Chancellery and the Berlin bunker. On the other hand, all these elemental dwellings refer to the beginnings of architecture, be it the rationalist enlightenment present in the treatise writer Laugier’s original hut or in Aldo Rossi’s elegiac shacks, be it the Adamic lineage that Americans customarily attribute to the Thoreau of Walden – a replica of whose cottage in the woods was built last year to celebrate the literary work’s 150th anniversary –, Asians duly assign to the cotton-weaving Gandhi, and Europeans ultimately find in the Heidegger of the Black Forest cottage, where the pre-Socratics stumbled upon the swastika in his abyssal exploration of technical modernity’s fragile foundations.

Skyscrapers express the formalist mannerism of contemporary projects, be it the Max Reinhardt Haus by Eisenman or the CCTV by Koolhaas, be it the proposal of United Architects for the World Trade Center.

Indeed, the primitive emotion of the elemental turns our sympathies towards the economy of means and the astringent purity of the hut, especially if we compare it to the strident clutter of forms that skyscrapers flaunt today, from Ground Zero itself, where Daniel Libeskind’s trivial winning project has been vulgarized even more by successive revisions – The New York Times describes the architect who 18 months ago capped the planet’s most coveted commission as “the incredible shrinking man”, and the MoMA, which has worked on rather low standards in its skyscrapers exhibition, excludes Childs & Libeskind’s Freedom Tower from a selection that includes three entries to the competition –, to the emerging Moscow of millionaires and gangsters, where the Dutch Erick van Egeraat has designed five picturesque towers based on canvases of five artists of the Russian avant-garde – Alexandra Ekster, Vasili Kandinski, Kazimir Malévich, Liubov Popova, and Alexandr Rodchenko – or to the Shanghai that is as fascinating for the number of projects it is carrying out as it is disappointing for the low quality of its high-rises. The formidable versatility of contemporary technology makes it possible to build anything at all, sparing architecture the discipline of necessity and placing it under the banner of a narcissistic spontaneity that often results in confusion, a caricature of the artistic liberty of the statue of that name, where Bartholdi’s sculpture and Eiffel’s structure are superposed with distracted autonomy.

But however seductive it is from the angle of the arrogant hypertrophy of the architecture of the Empire, the house of Bin Laden is the house of the enemy, and the American ‘neocons’ ruling the world from George W. Bush’s White House know this only too well. Disciples of Carl Schmitt via Leo Strauss – mentor of their intellectual leader Irving Kristol, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, and Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz through the Allan Bloom whom Saul Bellow portrayed in Ravelstein – this tight ideological group follows the German jurist in distinguishing between friends and foes and making such distinction a basis of policy, and it is in favor of active intervention, a large State, and a strong presidency, precisely the three traits that The Economist points out as the three characteristics of Bush’s mandate. It is this same group that has sparked interest in Hitler’s jurist among sectors of the Marxist left that are critical of postmodern nihilist relativism and the hypocritical impotence of neoliberalism, which has reduced the political sphere to the free market economy and the ethics of human rights. With Weberian realism, Schmitt never mistook the inimicus that we can evangelically love with the hostis inevitably placed by his otherness on the opposite side of the trench, and this is perhaps the essential distinction that reveals itself in an autumn of growing terrors, shrinking resources, and migrant identities, in this September that already foretells November.