Precipice and Protest

The economic crisis and the indignation of citizens marked a year that saw the spreading of social unrest, from the Arab awakening to the Spanish 15-M.

Metropol Parasol, Sevilla. Jürgen Mayer

The Protagonists of 2011 were an abyss and a clamor: the abyss into which European economies threaten to sink, struck by the debt and euro crises, in a fall that would affect the United States and even the booming emerging countries; and the clamor of protest against the political and financial elites, which sparked off in the Arab world, had in Spain’s 15-M the most noteworthy episode in southern Europe and reached the United States with the Occupy Wall Street movement. Both features, precipice and protest, are intimately linked, because the vertigo of the abyss is what makes populations accept unprecedented sacrifices, and the frustration with the sterility of those

Tahrir Square, Cairo

Cairo’s Tahrir Square was the stage for the uprising against Mubarak in Egypt; in Spain, the ‘indignados’ took up squares like Madrid’s Puerta del Sol or Seville’s Encarnación, under the controversial Metropol Parasol.

In our continent, the urgencies of the financial crisis – which led to the replacement of politicians with technocrats in the most affected countries, and quite singularly in Greece and in Italy – have pushed the planet’s other crises into the background: the climate crisis, which continues to worsen, with summits as that of Durban failing to take relevant decisions; the energy crisis, which has deepened after the damages caused by the March tsunami in the Fukushima nuclear plant, a dramatic accident that has put this energy source into question in Japan and in the world at large; and the geopolitical crisis, which was become even more complex with the US withdrawal from Iraq, the failure to contain Iran and the convulse uncertainty of the ‘Arab Spring’, a historical mutation that echoes with the violent death of two public enemies of the West, Osama Bin Laden and Muammar Gaddafi, and with the concentration of the superpower’s military troops in the Pacific theater, as befits the new scenario created by the impetuous rise of China – a country whose determined impulse barely leaves space for dissidence, as could be seen with the cause célèbre of Ai Weiwei, the artist and architect who made number one on the list of the most influential people in the art world, while suffering the arrest and harrass-ment by Chinese authorities.

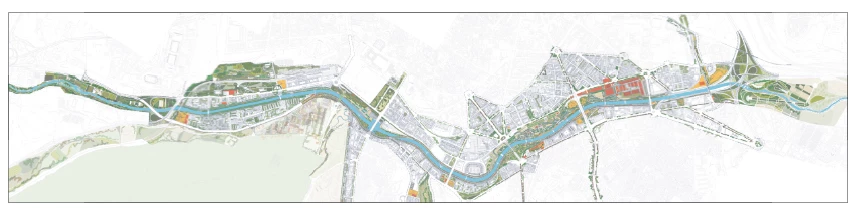

Diana temple, Mérida. José María Sánchez García

The dialogue with history defines interventions like those in Mérida’s Diana Temple, Berlin’s Neues Museum or Madrid’s Matadero; and dialogue with landscape, those of the Museum of Lugo or the Town Hall of Lalín.

In Spain, the industrial decline and housing crash, together with the contraction of public expenditure, have led to unemployment rates that reach 50% among the young, to an inversion of demographic flows towards emigration, and to a disappointment with the government that brought about overwhelming victories of the conservative opposition in the municipal and regional elections of May, as well in the general election of November. The bursting of the real estate bubble, along with the fiscal crisis of all administrations – central, regional and local – has had a devastating effect on architecture: the land market has practically disappeared, housing construction has collapsed to a tenth of the units initiated five years ago, and the launching of public projects has come to a standstill. The housing figures are particularly revealing: 865,000 units were started in 2006, barely 83,000 in 2011. Over half of the architecture studios in Madrid and Barcelona have closed down, a field that once escaped unemployment now has an estimated rate of 45%, and young architects migrate massively to northern Europe, Latin America, China or the Gulf.

The economic winter has also interrupted construction or activities in large complexes such as the City of Culture of Galicia in Santiago de Compostela or the Niemeyer Center in Avilés, has evidenced the disproportion of others that bring practically no economic or social profit, like the Olympic Stadium of Seville, the Arts Creation Center in Alcorcón or Benidorm’s Terra Mítica, and has unveiled corruption scandals linked to large works in Mallorca and Valencia, where Santiago Calatrava has had to face trial, a difficult junc-ture perhaps alleviated by his designation as cultural adviser to the Vatican. This desolate landscape has encouraged criticism against star-architects and iconic works – though it has not prevented the Fundación Botín from commissioning Renzo Piano with the con-struction of an emblematic cultural center in Santander –, and has also stimulated a new architectural culture of material efficiency and productive demand, present in the oeuvre of a builder-manufacturer like Jean Prouvé, which was exhibited in Madrid as a source of inspiration for the time to come

This depressing year was however brightened up by some good news, mostly in the uncertain border between the old and the new: we saw the completion of Madrid Rio, an exemplary landscape project materialized by a team led by Ginés Garrido; of the con-troversial Metropol Parasol by Jürgen Mayer in Seville and of the innovative Matadero of Madrid (an adaptation for cultural uses carried out by a group of young architects, among which Arturo Franco, Churtichaga Quadra-Salcedo, Langarita Navarro, Carnicero, Vila & Virseda or Antón García-Abril), two diametrically opposed examples of intervention in heritage contexts; and of the Museum of Lugo and the Town Hall of Lalín, two public buildings in Galicia whose openings coin-cided with another two accomplishments of their respective authors – Nieto Sobejano and Mansilla Tuñón – in the field of dialogue with history: the inauguration of the extension of the San Telmo Museum in San Sebastián and the FAD Award to the Atrio Hotel-Restaurant in the historic center of Cáceres. And there is no better example of that dialogue than the Roman Art Museum by Rafael Moneo, a build-ing which celebrated its 25th anniversary in the same city of Mérida where two significant works by emerging architects were completed, though along divergent paths: the material laconicism of the Temple of Diana site, by José María Sánchez García, and the polycar-bonate polychromy of the Factoría Joven, by Selgas Cano, a couple who also completed its celebrated Auditorium and Congress Center El Batel, in Cartagena.

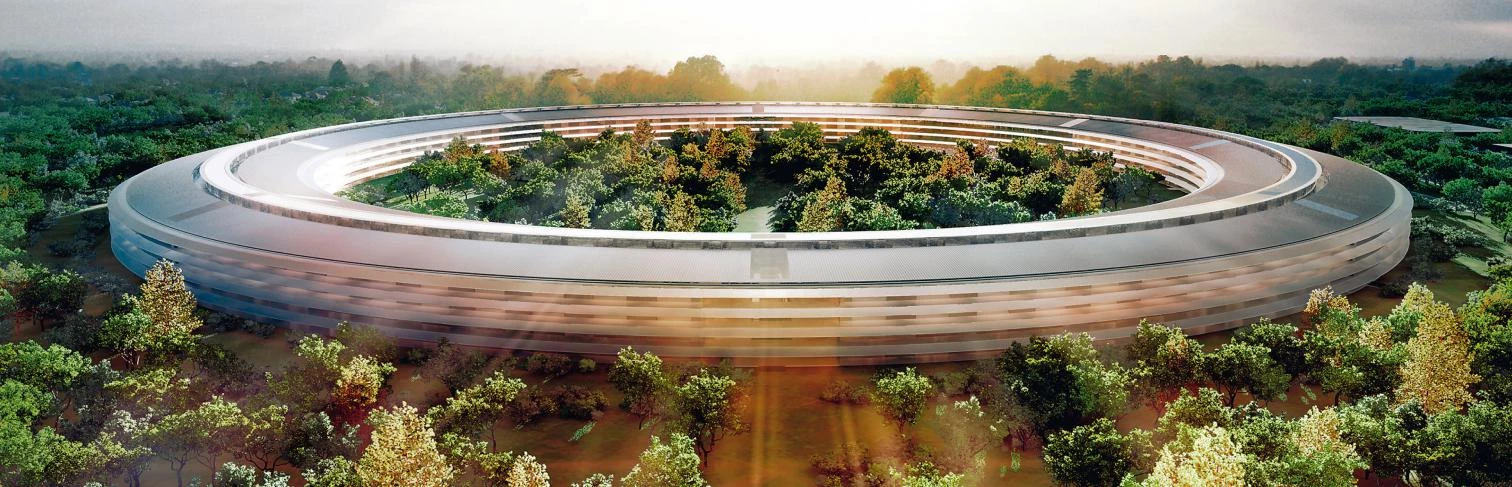

On the international stage it was the year of the Portuguese masters, Álvaro Siza, who obtained the UIA Medal, and Eduardo Souto de Moura, who received the Pritzker Prize and finished in L’Hospitalet a monumental still life of buildings; of the British David Chipperfield, who received the RIBA Gold Medal, completed his bold Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield, and won the Mies Prize for his admirable Neues Museum in Berlin, a work that reformulates the criteria for the reconstruction of historical buildings; and sadly also of the Mexican Ricardo Legorreta, who was awarded the Praemium Imperiale shortly before passing away on the penultimate day of the year, leaving the memory of his color-ist work and closing a list of disappearances which also includes the Spaniards Antonio Miró and Eleuterio Población, the Hungarian Imre Makovecz, the American Ralph Lerner and the Argentinian Mario Roberto Álvarez. But the year’s most noteworthy loss was undoubtedly Steve Jobs, a genius of design and business that leaves behind the Apple products and the project for the new headquarters of the company in California, a colossal futuristic ring, light like a space station and traced by the hand of Norman Foster, the same architect who inaugurated Virgin’s private spaceport this year.

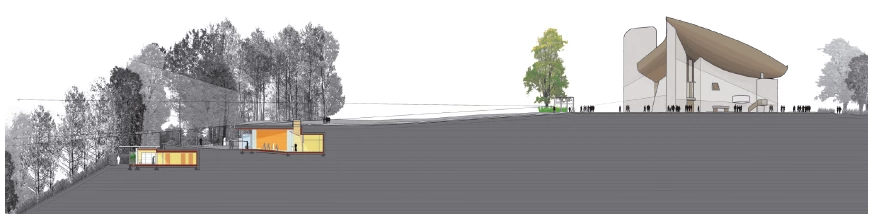

Nature guides Madrid’s new river park, inspires the weightless art museum in Teshima, wraps the austere convent of the Poor Clares in Ronchamp, and frames the futuristic Apple headquarters project in California.

Teshima Arts Museum, Ryue Nishizawa

Closer to earth, Zaha Hadid picked up the Stirling Prize for second year in a row, this time for Evelyn Grace Academy, a London school intertwined with an athletics track; Enric Ruiz-Geli won the Building of the Year Award with his Media-TIC, and designed a new building for the gastronomic experiments of Ferrán Adriá, after the foretold closing of El Bulli; and the young architects of Zig-zag received the Spanish Architecture Prize with a housing complex in Mieres, in a year in which Lacaton Vassal finally completed their exemplary refurbishment of a residen-tial tower, which opens new perspectives in urban regeneration. Flashes of hope, all of them, in times of distress, sprinkled in any case with projects of spiritual dimension, such as the empty museum by Ryue Nishizawa with the artist Rei Naito in the island of Teshima, the luminous church by Rafael Moneo in San Sebastián, and the exact cells for the Poor Clares built by Renzo Piano on the hillside of Ronchamp: precincts for meditation in a year marked by an array of economic precipices and ecumenical protests.

Apple, California. Norman Foster