Disciplined Play, the Latest Projects

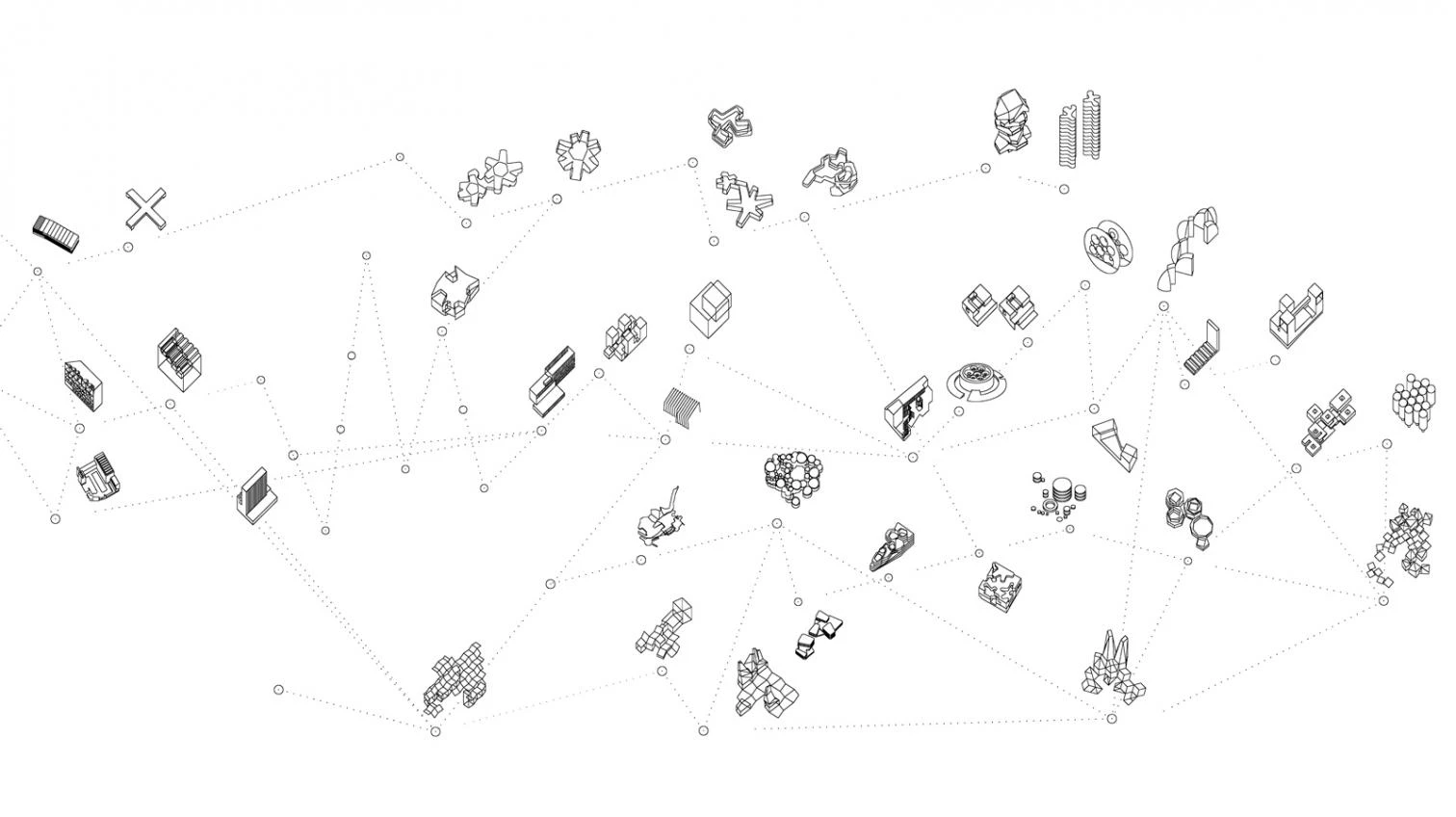

Mansilla & Tuñón’s 2008 competition winning scheme for the Energy Dome of the Soria Environment City begins with a few simple, rule-based operations. The starting point is a half sphere; an easy to describe geometric container, sized to accommodate the given program. A series of vertical cuts yield separate blocks, which are in turn unfolded to activate the site and define zones of use and activity. The closed, monolithic form of the dome is fragmented to create a new figural presence on site. The project moves from singularity to multiplicity – from the one to the many – without ever sacrificing the clarity of its starting point.

What is proposed here is not so much a singular operation as a method to realize the project – in principle it could be used to realize any number of related projects. There are many practical advantages. It is inherently flexible; should the building scope or program change (as is so often the case with a new institution), the blocks can be easily rearranged. The project depends not so much on a specific arrangement of pieces as on a set of rules that define the relationships between parts: a kind of grammar. The blocks are hinged, they touch at the corners, and they rotate to form courtyards or to capture distant views. As long as these conditions are maintained, any number of solutions is valid. The project can be built in stages, also a typical requirement of an institutional program in uncertain times. The cuts increase the surface area, opening up the interior to light and air, and they create a more transparent image for the institution. The curved arch forms, all segments of a sphere, are easily drawn and calculated, recalling the structural integrity of the original typology. And these clean, sharply rendered geometric forms have a strong iconic presence, capable of triggering multiple associations.

As is often the case with Mansilla & Tuñón’s recent work, the unfolding appears somewhat casual, as if the blocks were scattered on the table without over-thinking their arrangement. It is true that this freshness, this immediacy, is a large part of the attraction of Mansilla & Tuñón’s work, and something they strive for. It finds clear expression, for example, in one of their most recent projects, the winning competition scheme for the Vega Baja Museum. Nor is it accidental that a recent exhibition of their work was entitled ‘Playgrounds,’ as if this scatter of forms is the aftermath of an artfully played game. But don’t be deceived; the effect of effortlessness can only be achieved through concentrated effort. (Or, as Luis Mansilla has remarked, quoting John McEnroe, “the more I practice the luckier I get.”) Nor is this casualness an end in itself. Just as a composer works freely with an abstract notation even while looking for a specific musical effect, Mansilla & Tuñón’s precise architectural intelligence allows them to play with form with a full awareness of anticipated architectural effects.

A careful look at the plan confirms the logic behind the arrangement. The project spreads out across the length of the site, loosely mirroring the curve of the Duero. The building has a clear front and back. It takes advantage of the concave and convex profiles of the blocks to create varied exterior spaces, bringing nature close to architecture and architecture close to nature. This ‘constellation’ of profiles creates an irregular courtyard for the primary programs (an inward looking space that consolidates entry and movement), while secondary programs enjoy a more separate existence, oriented outward.

What is astonishing here is how such a simple series of operations, a process so apparently mechanical, could yield such a rich and varied series of architectural experiences. The plan is logical, meticulously resolved, yet full of surprise. The power of the project is in the precise calibration of the contingent and the absolute: the seemingly arbitrary cuts and rotations resolve themselves into something that appears inevitable yet is completely unforced. Without falling into the picturesque, the plan has something of the complexity of a small urban fragment: an assemblage that has grown over time, through a process of accumulation, to create plazas, pathways, compressed spaces and expansive vistas, but without sacrificing the singular identity required of an institutional program.