Cinema Constructions

Two documentaries about Gehry and Foster portray from opposite angles the architectural profession, between artistic genius and choral orchestration.

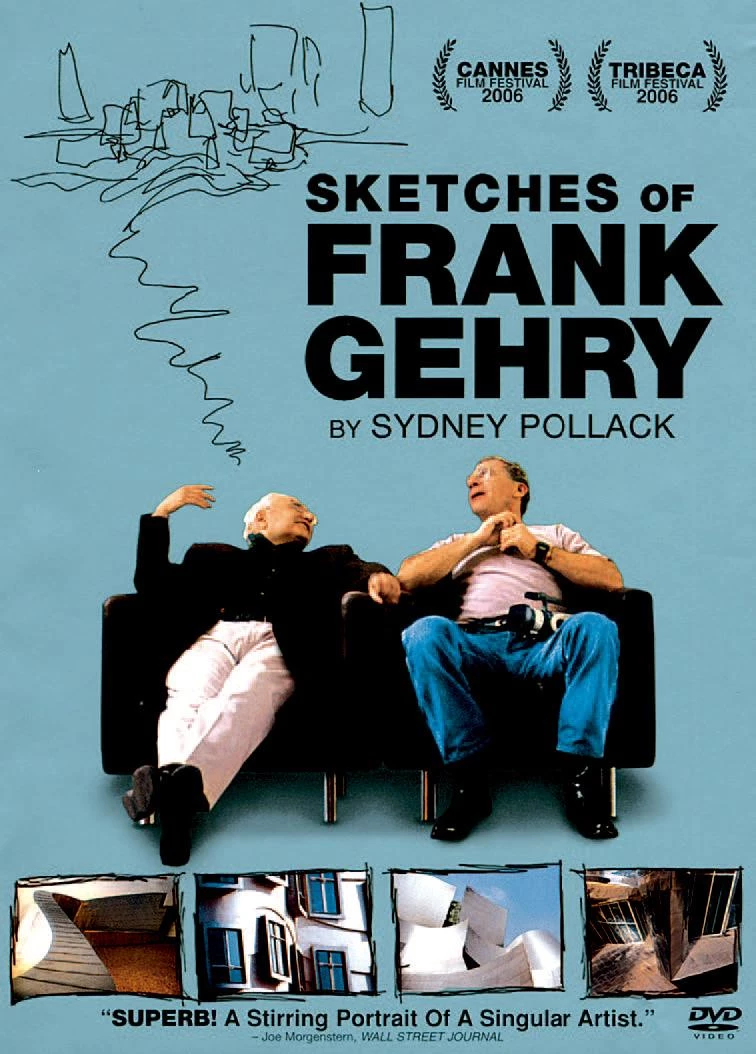

Architecture loves cinema, but rarely is this love reciprocated. Though the moving eye of the camera has often fed on contemporary buildings, cinema has seldom sought to unravel the mechanisms of the creation of spaces, preferring as it does to stick to the use of architecture as a setting and the occasional stardom of cartoonish architects. Three years ago, Nathaniel Kahn’s film about the legendary Louis Kahn, titled My Architect: A Son’s Journey, was a moving account of an illegitimate offspring’s voyage to his biographical origins and to the very heart of architecture, a self-contemplating, bitter and perplexing portrayal of the father he hardly got to know and the master whose footprints he looked for in impassible buildings. It was also tangible proof of the poetry and emotion with which cinema can begin to pay its debt to the world of construction. This last season, Sydney Pollack’s documentary about Frank Gehry and Mirjam von Arx’s about Norman Foster’s London ‘gherkin’, premiered almost simultaneously, offer openly opposed views of the social, artistic, and urban role of architecture, and of the processes of professional collaboration, economic negotiation, and political strife that surround it.

The recent films of Sydney Pollack on Frank Gehry and of Mirjam von Arx about the construction of Norman Foster’s London ‘gherkin’ were preceded by the documentary of Nathaniel Kahn on the life and work of his father.

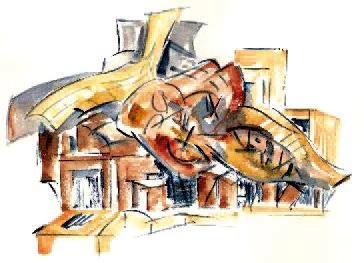

In Sketches of Frank Gehry, the Hollywood director delineates his architect friend with the hyperbolic strokes of the genius, and as much in relaxed conversations as in numerous interviews with corporate clients and artist colleagues, the veteran master of Los Angeles comes across as a smart playful child who creates beauty with distracted spontaneity, however much his alleged need to suffer because “it is wrong when too easy.” But the film director refutes Gehry’s words by filming him in the act of drawing his lyrical tangles of lines with astonishing ease, or building small models with cardboard and tape, pensive at times but jubilant for the most part. Then the architect expresses his admiration for painters and claims he has never managed to achieve “painterly surfaces,” a gesture of modesty that Pollack counters with a fascinating succession of iridescent and undulating facades. In the end, the model is good “when stupid looking.” “What is the material?” “I do not know yet.” In any case, “buildings take so long that by the time they’re finished I don’t like them.”

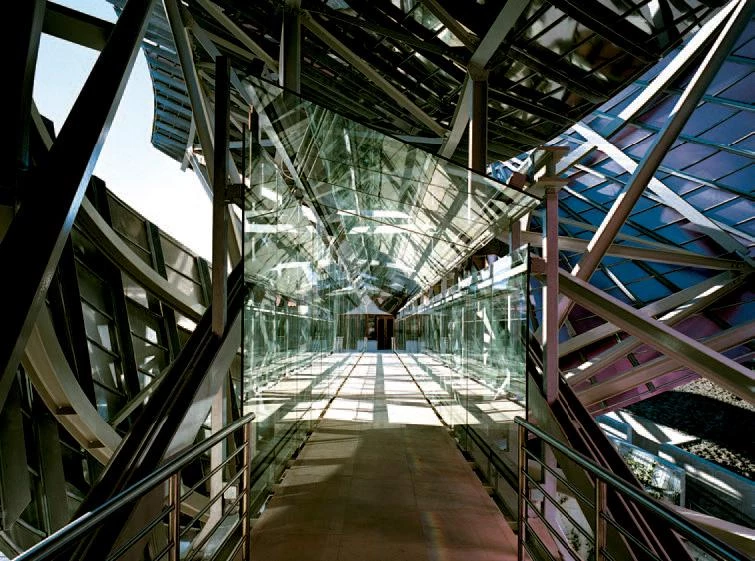

The hotel in the Marqués de Riscal Wineries uses the characteristic titanium and steel waves of Gehry to shape two volumes connected by a footbridge, providing spectacle for visitors and a high-profile icon for the wine brand.

From Disney’s Michael Eisner to Vitra’s Rolf Fehlbaum to the Guggenheim’s Thomas Krens or Dennis Hopper who lives in a house designed by Gehry, all his clients come together in a polyphonic litany of admiration. The artists, from Ed Ruscha or Chuck Arnoldi to the ubiquitous Julian Schnabel, join the chorus of praises, and the few architects interviewed, from an already very weakened Philip Johnson to the critics Charles Jencks and Herbert Muschamp, voice opinions of applause or enthusiasm. Only the historian Hal Foster puts a note of censure, but it is so confusedly expressed that it only serves to legitimize the complacent tone of the over-all portrait. In this ocean of flattery, the most picturesque figure is Milton Wexler, Gehry’s psycho-analyst of the past 35 years, who denies responsibility for the architect’s creative transformation (it was after beginning therapy that Gehry gave up the conventional architecture he had been building) and explains how he discourages many an architect who comes to him in search of a miraculous recipe after hearing of his method.

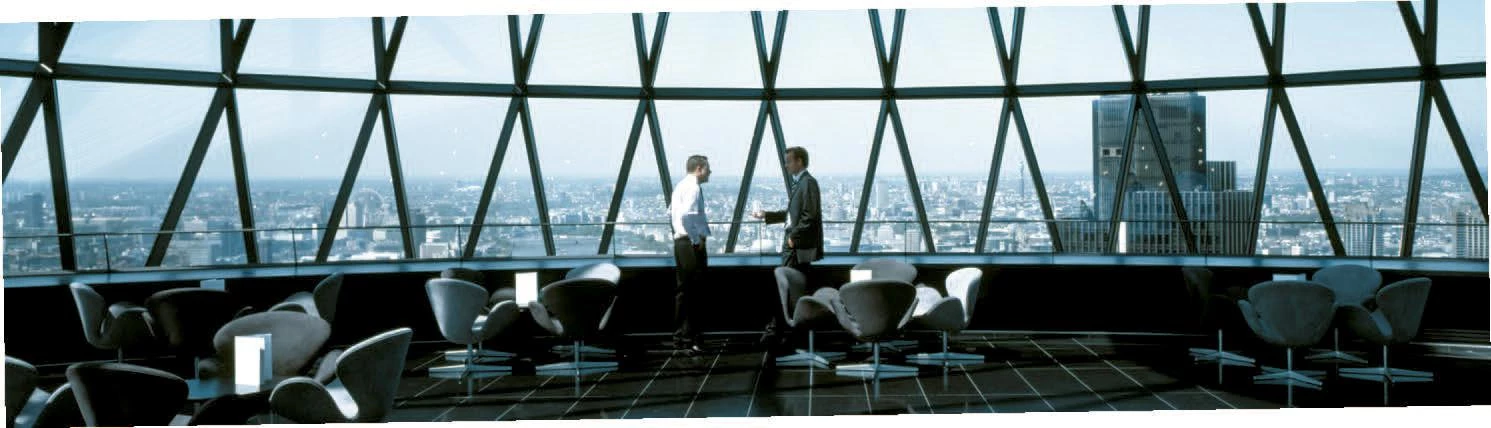

With an approach almost diametrically opposed to the Californian exaltation of individual inspiration, Building the Gherkin presents the building of the London skyscraper as a collective endeavor, and with admirable plausibility the young Swiss director Mirjam von Arx manages to convey both the complexity of the political and media scenes that surround architecture and the diversity of its technical and corporate protagonists. Combining the emotive spectacle of high-rise construction with a narration of the labyrinthine ups and downs of planning and the inevitable conflicts and crises unfolding in the course of development, the documentary is at once an epic and a comedy of manners. As such, it is as pedagogical in its account of the execution and decision-making processes as it is perceptive in its portrayal of the people involved. This is a long cast of managers, bureaucrats, designers, and building contractors: from Norman Foster himself, who argues with frozen laconic accuracy, to the almost sinister municipal urban planning chief, Peter Wynne Rees, passing through the representatives of the client, the insurance firm Swiss Re, who are led by a formidable, intimidating, warm-blooded Sara Fox. All are portrayed with empathy and humor in the documentary, where their indecisions, phobias, and disagreements together make up a vital and vibrant soap opera.

The skyscraper rises on the site of the Baltic Ex-change, a building blown up by the IRA. Construction had begun when the attacks of September 11 happened, so the film addresses the impact of terrorism on both the safety of high-rise buildings and the balance sheet of the insurance company behind the tower. These dark shadows are balanced with episodes of high comedy, such as those documenting the decision to assign the interior decoration to another firm, to Foster’s huge dismay. The result of four years of work, the documentary about the first skyscraper to go up in the City in twenty-five years – which started out as a controversial project and ended up becoming a symbol of London, appearing in movies like Basic Instinct II and Woody Allen’s Match Point – is above all a detailed description of how architecture gets entangled with life itself, and a lucid and critical tribute to the men and women who make possible the miracle of turning sketched dreams into real space. In this implausible territory, Foster and Gehry are not far apart. The recently completed pyramid of the Brit in Kazakhstan seems as oneiric as the dizzying, ethylic forms of the Californian in Álava’s Rioja region. In the end all we have are shadows, cinema constructions, dreams of reason or incubi of reason in slumber.

The Pyramid of Peace in Kazakhstan resorts to the triangulated structures employed by Foster in other projects to erect a political symbol and an urban landmark, topped by Brian Clarke with a stained glass with doves.