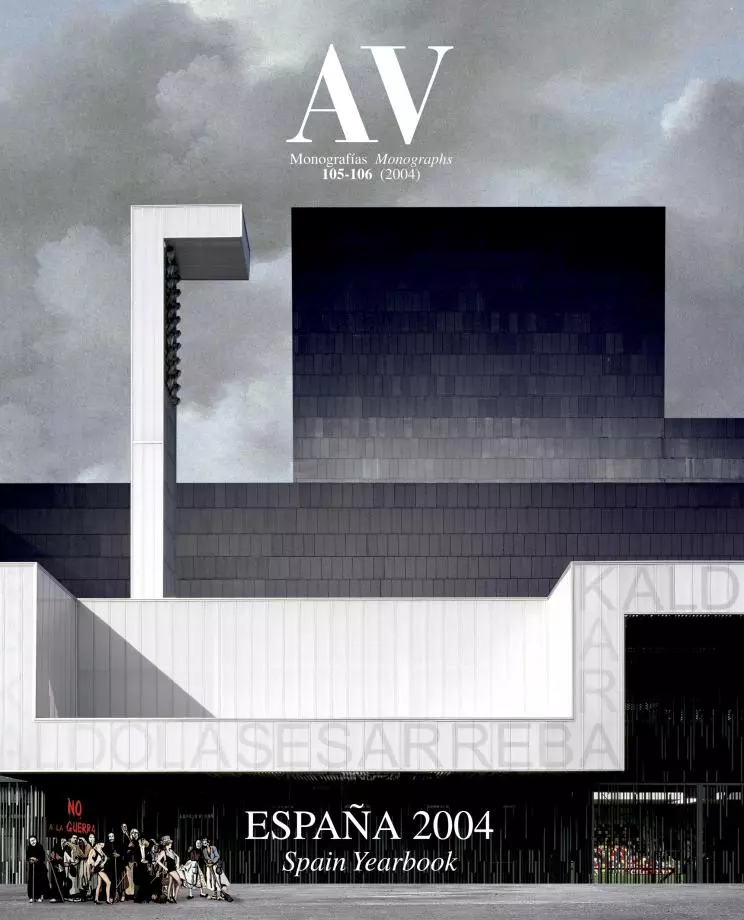

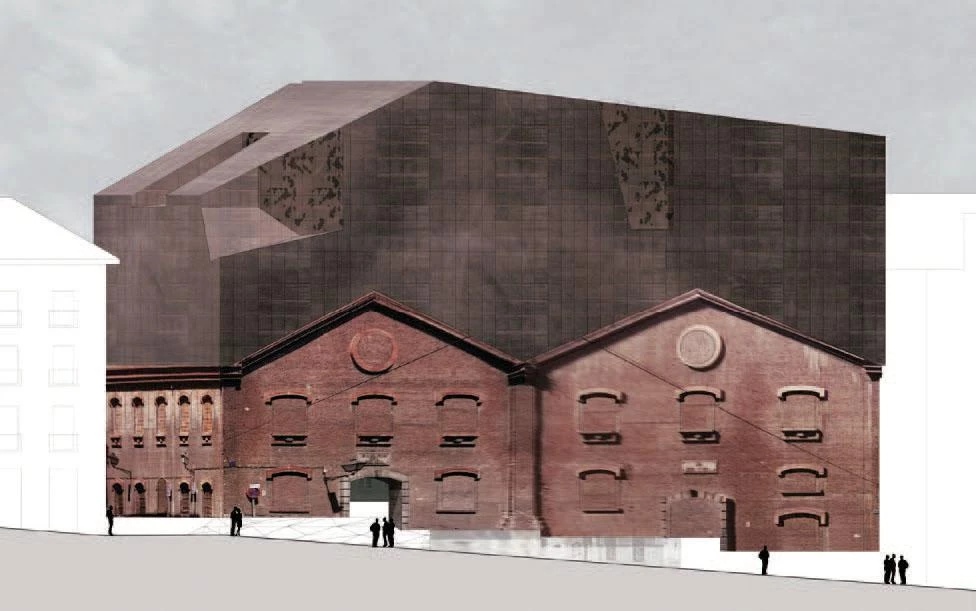

They say that the Swiss build boxes. But the project of Herzog & de Meuron for the art center of La Caixa in Madrid is a different kind of box. Filling in the windows of a brick warehouse built in 1900 as an electric power station, editing out the granite plinth to excavate a new public space under the building, and crowning the whole with a cast iron top whose shape evokes that of the surrounding roofs, the Basel studio proposes a strongbox which is also a surprise box, with its solemn and hermetic volume magically levitating over a square warped as an untamed carpet. Sponsored by a sav-ings bank, this strongbox is a resonance box for the financial institution, and also a boîte à miracles for the ceremonies of contemporary art: if the Swiss build boxes, these are cranial or thoracic boxes that contain at once thought and emotion, memory and viscera, calculation and passion. In Basel, a city of long cultural and artistic tradition where the logic of money is fertilized with pharmaceutical alchemy, and where this studio of 170 architects and five offices in three continents is based, Jacques Herzog comments on architecture, art and museums.

Translucent that which houses the Laban Dance Centre and opaque that designed for the Fundación La Caixa, the boxes of London and Madrid are a result of one same desire to make the space for art public.

If you see what is in the pipeline, you can see the dramatic changes in outlook that are taking place, arising from our increased experience, the technology of computers, which has given us new tools, and the new understanding that comes from working in different geographies and circumstances. The fact that we have to be understood in different cultures somehow cancels the more innocent way we have been working so far. Whatever we have done in Europe, is modernist, a product of the Enlightenment. It was supposed to follow a tradition of research, innovation and dialogue. How can we reconcile this with the economic and political forces emerging after the fall of Communism? Now we are living the end of the hype of the nineties, with the fall of the stock market, which was the image of endless growth. It is true that some of the clients that have been selecting us because we are stars in the market are based on this ideology of luxury, and I am not unhappy that this is ending also. On the other hand, who pays to do a research such as Prada? If you take someone like Bruce Nauman, one of our heroes and perhaps the most significant living artist, you see his work is based on a kind of innocent research. He has his own laboratory, and he looks at every single thing that surrounds him and tries to find connections, about how this world functions. Art is about understanding where we are, where we go, so in some way it is replacing religion, through some sort of enlightenment which enables individuals to get closer to themselves, to nature, and even to God. Our architecture is a tool of understanding how we live together. Paradoxically, architecture is not about content, materials or form: it is about perception, about giving people an understanding of themselves, and this is of course the ultimate goal one can have in life.”

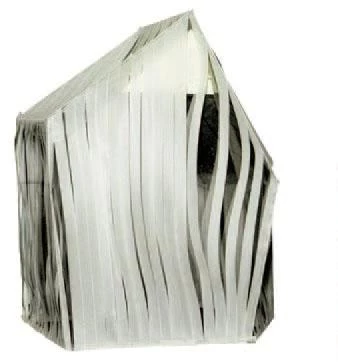

Halfway between crystallographic figure and archetypal house, the Prada building in Tokyo is ‘dressed’ with the glamorous aura of fashion and successfully tries an alliance between image, structure and space.

“Some time ago, in Venice, I participated in a panel about the future of museums and architecture for art, and I found the whole thing disgusting, with a hypocritical atmosphere and Libeskind saying things like ‘I don’t know the future of museums because I dont’t know how artists would work in the future’, something ridiculous particularly in his case or Gehry’s, whose architecture does not depend on the artworks that go in their museums. I defended that if there is one model that is not for the future, it is the Guggenheim’s, a cynical demostration of global behavior by a global company. In our case, to produce significant work, we need clients that can act as accomplices. If you compare Thomas Krens and Miuccia Prada, you can see what I mean. Miuccia is a true artist, one of the most extraordinary persons I have met as a client. In the projects we have done in the recent years she really has acted as an accomplice, never trying to stop you but to push you. Nick Serota is also a great client, and a very demanding one. I have told you several times, the process of doing the Tate was one of the more exciting in our career. And we have maintained our relationship with Serota collaborating in the installations of the large artworks of the Unilever series in the Turbine Hall – Louise Bourgeois, Juan Muñoz, Anish Kapoor, Olafur Eliasson –, and making small changes, treating the Tate almost like a landscape we have to adjust. We had other clients, like the Moeuix or the Kramlichs who were also very helpful, but only Miuccia and Nick Serota are significant in the global scale. I hope we can keep this kind of dialogue with clients, because we have very often worked twice or three times for a client in the past, maintaining the contact once we have finished the building, as in the Tate. There, for instance, we have always been worried about natural light, trying to improve its con-trol and its mixture with artificial light. In the Caixa we were surprised to find there was no demand for natural light, as it also happened in New York’s Fon-dazione Prada, where the curators again asked for no natural light. But we always insist on the need for daylight, which changes the scale of things, and architecture is all about scale. For all of this we need a working dialogue with the client.”

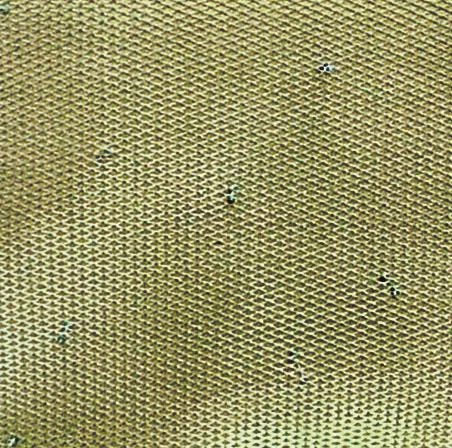

A manifesto against the recent mediatic architecture of blobs and bubbles, the Schaulager in Basel is charged with archaic echoes: in its bold shape, in its solid walls and in the profusion of textures.

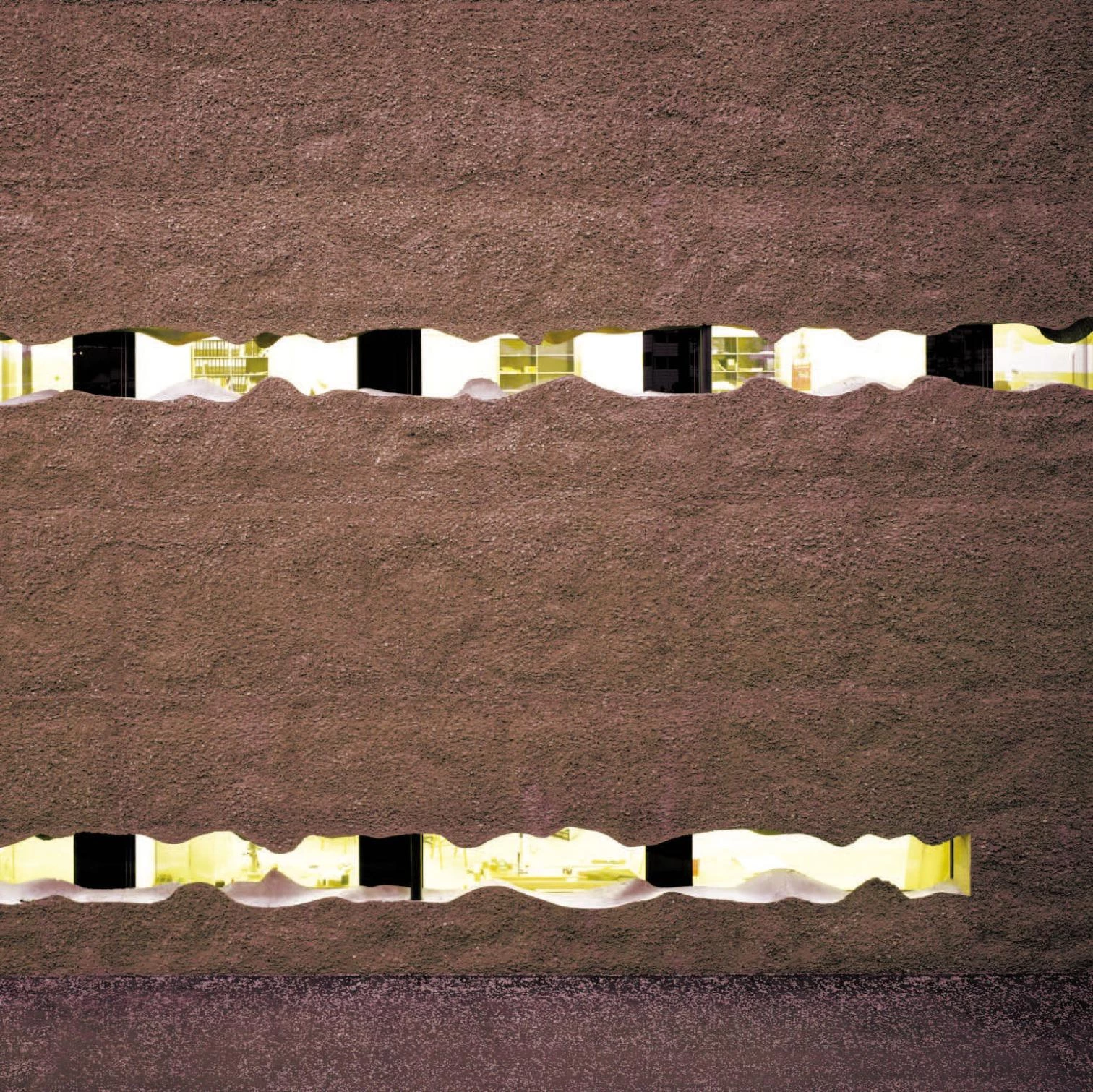

“Now we are presenting the Schaulager, and I am extremely happy that it comes into the open at this time. In contrast with the flashiness of other things we are doing or have done, and especially things which are on the market – like bubbles of the stock market in the nineties, grown out like vanity boxes – this is a totally different statement, modest and grand at the same time, and not only in scale. The kind of earthly power it boasts makes it a significant statement against bubble architecture, although not a generational statement against digital architecture. Because the Schaulager has this earthy side, but is almost digitally produced, almost out of genetic engineering. So it has these two sides, and it is interesting that it contains this computerized world, these new materials, and at the same time shows an extreme firmitas and an almost stupidly simple way to build a building. It is about stor-age, about layers, about digging out, about reusing materials because they are there and are good, about earth walls, about so many things that are so simple. Ideally you can deal with simplicity in such a straightforward way... In this case there is also an amazing trust of the client, who is an extremely wealthy person but with an incredible modesty. We should be careful not to take modesty as the over-all moral value, but unfortunately it is true that, for someone to be doing such a building, you need an incredible combination of money, flair, commitment... and also modesty, you know, because it is the anti-Guggenheim model.”

On the other hand, Prada was clearly a building started in the spirit of the nineties, with its seem-ingly endless growth of money, and fashion spread-ing around, something in which I no longer believe. Even if it is a flashy building, it focuses on fashion and clothes. Changing and looking are its core, so it brings fashion to its most interesting moment, which is beauty and magic and mystery: hiding and revealing, like the building itself. The way you look into the building or the way the building looks at the city, it’s all about perception. Although of course it is also a jewellery box, a beautiful object with fashion in the center, in contrast to Rem’s concept in New York, which presses everything in the low level, and uses the ground floor for other things than fashion, seemingly more important or higher.”

“Today, as always, I am interested in material architecture, but also in simulation, which is not mimicking a figurative world and bringing out a dinosaur. It is of course using figuration as a possible tool. Tenerife is a project about simulation, but we changed it so many times that one doesn’t know how much is artificial and how much figuration. What’s the process of transformation? This is ultimately the subject of 20th and also 21st century architecture. What is the degree of abstraction? When does technology come in? I think we have tried to reintroduce ornament in architecture, after Loos criticized it in a stupid, racist way. Ornament which is more than pure decoration, which is part of the language of the project and the genealogy of forms. Simulation is different. Postmodernism claimed that everything is simulation, but this does not exclude the reality of the world. I wouldn’t use simulation to refer to this fantasy that we call Disney-world, an anti-world to mask the reality of things. I would use simulation as a tool to transform reality, to create reality in a new way, like biotechnology could be said to be a tool of simulation. I still like those architectures where you can recognize every single thing: a brick is a brick, a stone is a stone, a piece of wood is a piece of wood. But there are other architectures like the Schaulager, where things are totally transformed, so much that you have to get closer to understand what it is. You can come behind reality, understand it and grasp it. In Disney you see a form, but when you come closer, the whole reality falls apart. This is the end of the dream. It’s a total disappointment, it’s all fake.”

“What makes the world strangely more real is the fact that you can visit other places and come back, let’s say, from China, and see this world here in a totally different way. That’s why I am happy to work in other parts of the world. It helps you to understand your own attitude. I must learn from them, because I want to adapt to be able to survive, and that’s also a philosophical point. The world, as it changes, runs away from you and you can no longer grasp it. When you are young you grasp it, like my little daughter. That’s something I can no longer do, because the world is changing in a way which over-comes me. But I think that at least you should be able to see what kind of a wave is going over you.”