Bailando con cadenas

Tanto el tsunami de Japón como el terremoto político del mundo árabe han evidenciado la fragilidad de nuestras arquitecturas materiales y sociales.

The physical tsunami of Japan and the lustrate the contrast between the exemplarity of peoples and the corruption of elites. Above all, they have thrown light on the fragility of our material and social architectures. Two civilizations have each initiated a process of mutation at the turning point provided by an unexpected tremor, provoked by the accumulation of tensions on the edge of a tectonic plate or the base of a demographic pyramid. In both cases, a small event – a geological microfissure, the confiscation of a street vendor’s weighing scale – has been the butterfly’s wing beat stirring up a hurricane: after the tsunami and the nuclear catastrophe of Fukushima, Japan will be a different country, and maybe its millenary refinement will manage to tame the hypertechnological autism of its consumerist culture; and after the gale of anger that spread from Tunisia and Egypt to Syria, Yemen or Bahrain, and that has provoked a war with the intervention of the western powers in Libya, the region will never be the same again, nor will the self-awareness of its peoples.

In both Japan and the Arab world we have watched and admired the disciplined dignity of populations: the hurt stoicism of those affected by the catastrophe and the peaceful protest of the humiliated and excluded, a guiding thread of decency that connects the orderly Japanese evacuations to the happy choregraphy of Tahrir Square, the optimistic resolve of which forced Mubarak to step down in eighteen days. In contrast the political and business classes of Japan and the rulers of the Arab countries, put to the test by disaster or uprising, have shown themselves incapable of representing or leading their people in historic moments of emergency. One might argue that the insufficiencies of Japan’s democracy cannot be compared with the abuses of Arab autocracies, origin after all of the revolts sparked by Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution: the Japanese prime minister, pathetically wrapped in work overalls, certainly seems very different from the picturesque fanfaronades of Libya’s Gaddafi and his drag queen getups. Nevertheless, the hierarchical and theocratic universe of the empire of the Sun – whose last representative addressed himself to his people for the first time since Hiroshima – still impregnates Japanese society, just like the exceptional charisma of leaders like Bourguiba or Nasser still echoes in the armies that have facilitated the Arab transitions, and that now look to Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey as a model of economic success where Islamist parties coexist with the lay military caste created by Kemal Atatürk.

The undersea tremor whose huge wave hit Japan and the whirlwind of rage that began in Tahrir Square and shook the Arab world coincided in time and, in spite of their diversity, both events offer similar lessons.

The handling of the crises by the Japanese and Arab elites has brought to light their self-withdrawn or corrupt alienation from the needs of the population: if the incestuous relations between government and industry in the archipelago are to blame for the insufficient security and informational opacity that the Fukushima catastrophe has revealed, the fire of indignation that spreads through northern Africa and the Middle East has exposed the obscene enriching of ruling classes incapable of creating decent living conditions for the young, who are denied freedom and hope along with prosperity. Time and again we see Islamist organizations taking on social functions where the Arab states have been unable to; and in the wake of the Japanese tsunami we again saw the Yakuza – like after the Kobe earthquake of 1995 – organizing help for victims and preempting the state in starting up emergency soup kitchens. Though the latter seek social acceptance and the former a part in national reconstruction, both episodes highlight the incapacity of the ruling elites to rise to a historic challenge.

These two great mutations will alter the face of two civilizations, but they will also irreversibly modify our own landscapes. Ja-pan’s still considerable weight in the world economy, along with its continued techno logical leadership in key areas, joins Eu-rope’s links with its southern Mediterranean neighbors, essential in matters of security, immigration and energy. In the final analysis, this last chapter could be the one that most profoundly transforms our societies, our cit-ies and our habits. To our dependence on the oil and gas of northern Africa and the Gulf we now add the inevitable reconsideration of nuclear industry, provoked by Fukushima, to trace a panorama that will situate energy at the center of the political debate. It is doubt-ful that the disaster in Japan will paralyze the construction of nuclear plants, just as 9/11 did not, as so many at the time predicted it would, bring on the end of skyscrapers; but the new safety requirements are likely to make them extraordinarily costly, maybe even unfeasible in most cases. Energy short-age can stimulate an accelerated transition to forms of urbanism and architecture that are more economical in construction and main-tenance: cities that are denser and buildings that adapt better to climate; two areas where both Islamic and Japanese culture have lots of lessons to offer us, as not in vain have both traditions fertilized our own at differ-ent moments of history, from the courtyards and lattices of Al-Andalus to the modular and translucent lightness of the most simple, refined and essential modernity.

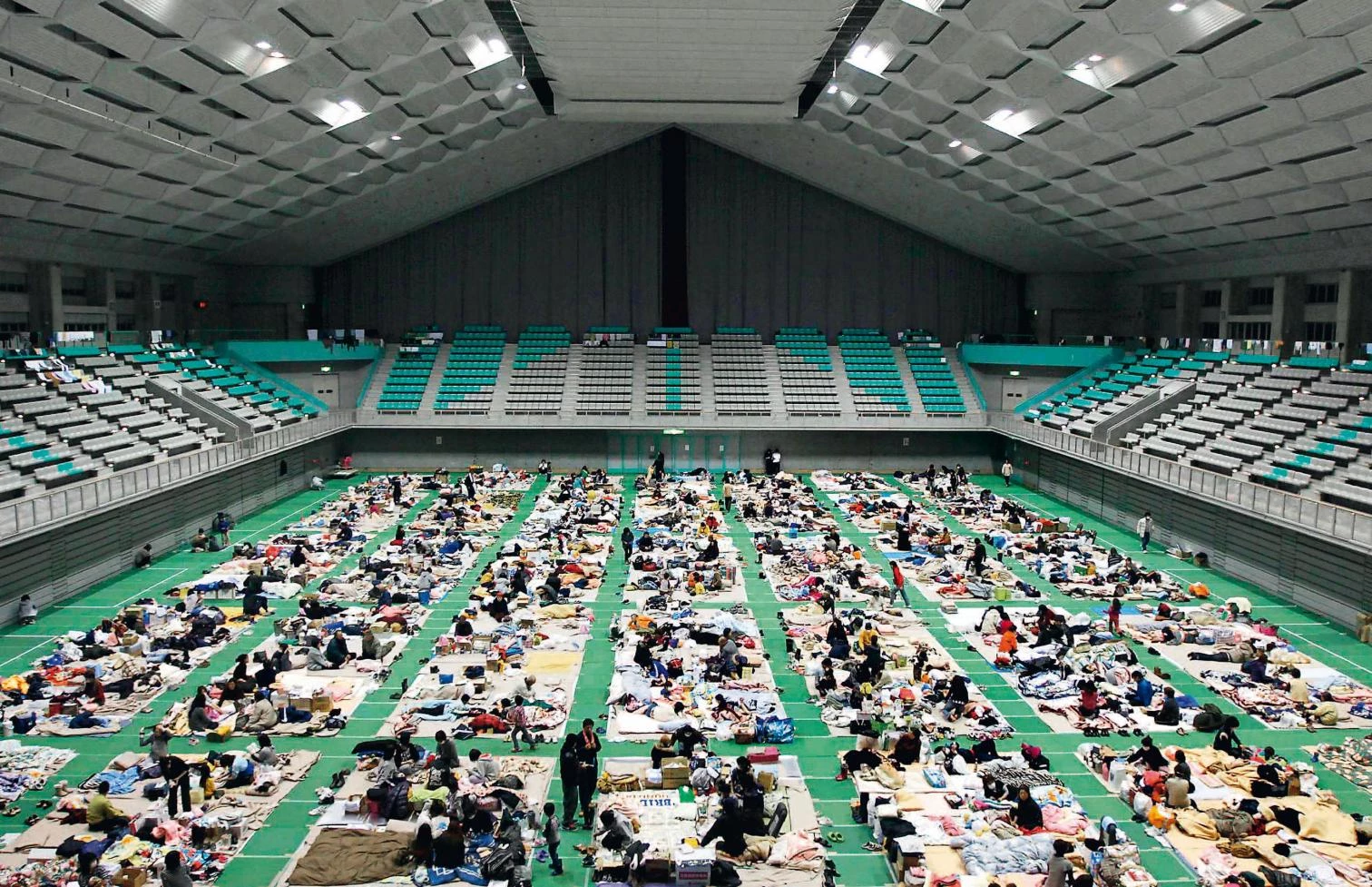

While the elites faltered, the masses of Egypt (above, praying in Tahrir Square) or the people of Japan (below, two examples of emergency shelters) showed admirable organizational skills and discipline.

The building cultures of Islamic nations and Japan teach us to create comfort and beauty with limited means, producing po-etry in a framework of restrictions, and this might be the glowing intuition that Nietzsche expresses in Beyond Good and Evil when he speaks of “dancing in chains”. At a re-cent jury in Beijing, convened to choose a design for a large museum of modern and contemporary art, the institution’s director responded to my curiosity about his maneu-vering capacity by momentarily doing with-out the interpreter we had been using until then, and looking me in the eye, letting out the only phrase in English I would hear him say during those three days of meetings: “I am dancing in chains”. I thought that it was a good portrait of the modernizing elites of today’s China, but it may be an even bet-ter description of the challenge awaiting us, wherever in the world we happen to be.