Knowledge Atmospheres

Spaces for Popular Science

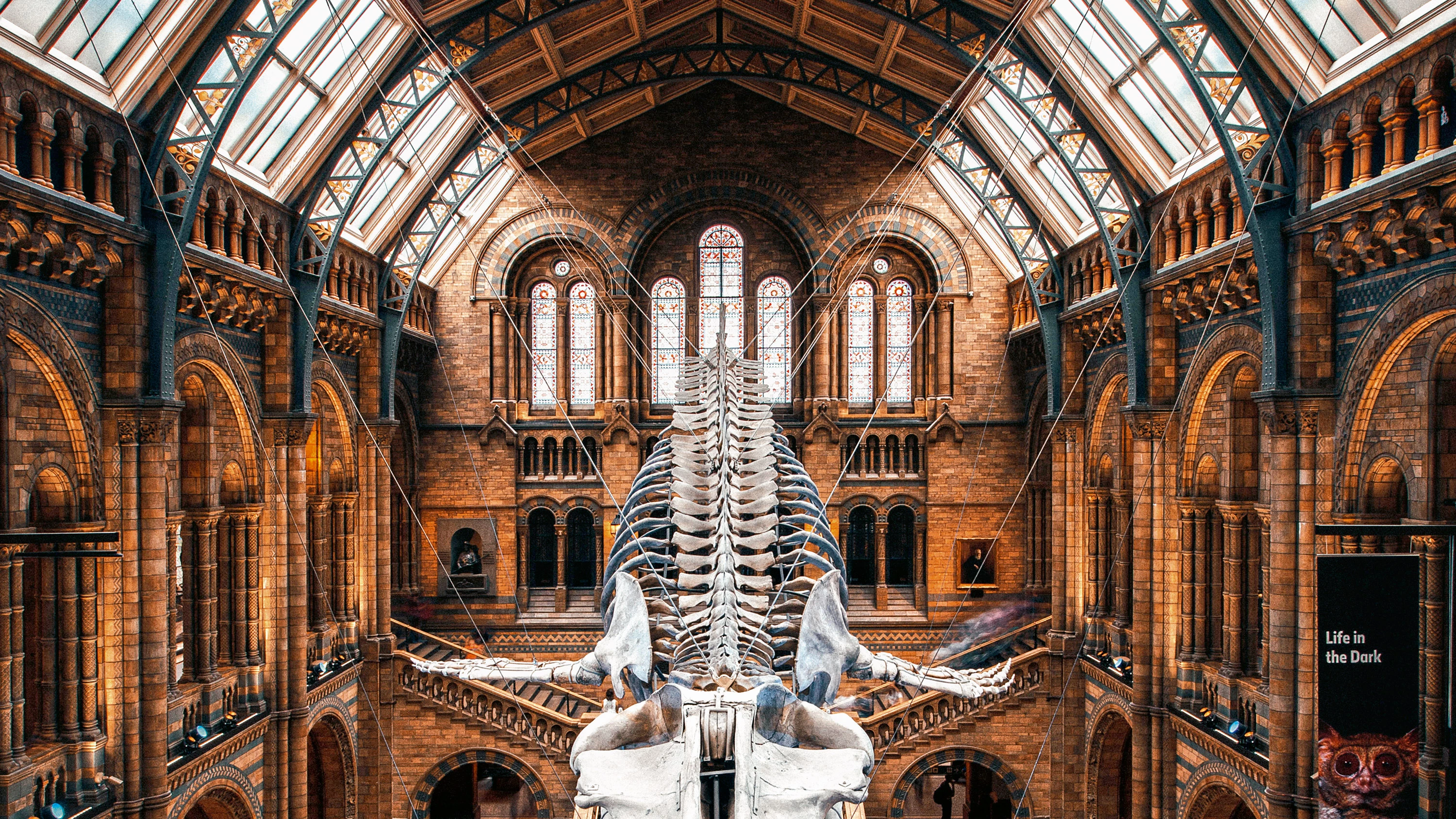

Alfred Waterhouse, Natural Science Museuml, London (United Kingdom) © William Parkinson / Alamy

Architecture has had so many ties to the hard power of politics and religion that we can easily forget how it has also always, from the very beginning, served the soft power of science. Weren’t the Babylon ziggurats towers from which to observe the sky? And the pyramids markers of the sun? Wasn’t the circle at Stonehenge an astronomic calendar? Didn’t the Romans erect a huge sundial at the Campo Marzio? And the Rajas of Jaipur the cosmic instruments at Jantar Mantar?

With the Modern Age and the knowledge revolution of the 17th century, the symbolic links between architecture and the forces of nature began to weaken, but on the other hand, buildings appeared that bore traces of rationalism and whose function, beyond transcendental analogies, was to serve the new science. So it is that the popes ordered the construction of the Torre dei Venti in the Belvedere of Rome with the intention of reforming the Julian calendar; the King of Denmark financed the Uraniborg observatory, thanks to which Tycho Braje paved the way for Kepler to derive his laws of planetary motion; Louis XIV had Claude Perrault design the Paris observatory, enabling the Cassinis to trace the French meridian almost at the same time that Charles II of England commissioned the Greenwich observatory in pursuit of his own meridian.

And although this tradition further grew with the advances of the 19th and 20th centuries, giving rise to new observatories like the Einstein Tower by Mendelsohn (recently restored), it soon broadened in scope to cover not so much the world of research as that of dissemination. Hence the appearance of a long list of museums, information centers, and theme parks that now envision themselves as hubs of knowledge and even immersive experiences aimed at introducing the general public to the arcane and increasingly abstruse world of contemporary science.

Featured in detail in this dossier of Arquitectura Viva are two works that connect with the endeavor to share out science spatially and scenographically, both designed by prestigious international practices. The first one, carried out by Renzo Piano Building Workshop outside Geneva, is the CERN Science Gateway, composed of twin tubes of steel and glass inside which the evolution of elementary particles and of the universe at large, in the course of nearly 14,000 millions of years, can be studied. The second, completed by Zaha Hadid Architects, is the Chengdu Science Fiction Museum, a spectacular building made of sinuous routes, immersive atmospheres, and powerful contrasts between the interior and the exterior, which despite not in the strict sense presenting scientific contents and materials, does harness the genre that, through literature, film, and videogames, has in our day and age contributed the most to the spread of scientific ideas.

James Stewart Polshek, Rose Center for Earth and Space, New York (United States)