Agoras and Symbols

Two Libraries in the East

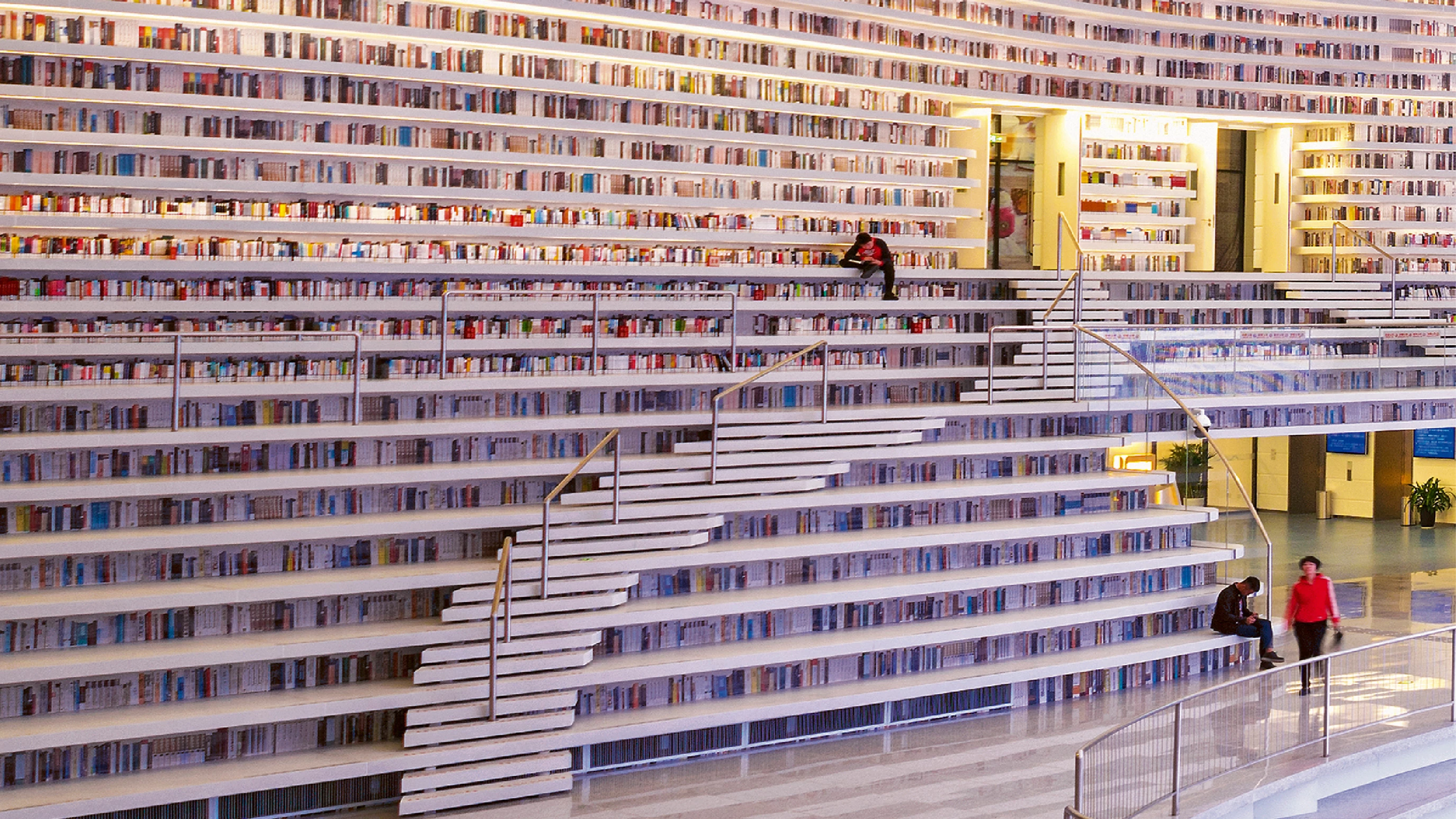

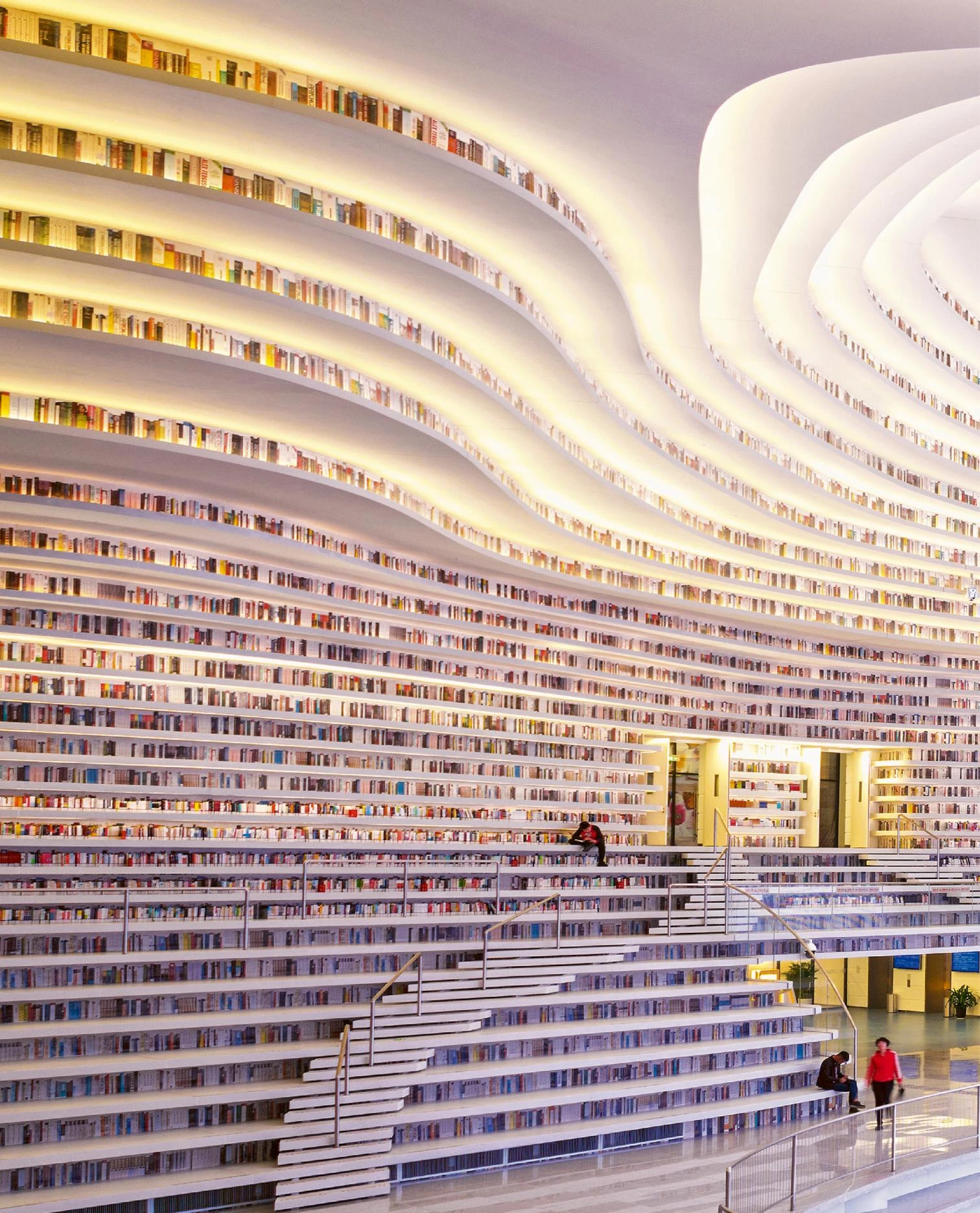

MVRDV, Tianjin Library (China)

Among all architectural groups, the family of libraries is one of those that have most undergone transformation, thanks to the double – and almost always complementary – action of globalization and digital change. At least from the Enlightenment on, libraries hooked up with the reformist drive and the ambition to build societies founded on knowledge, and became indispensable to the bourgeoisie that would develop in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, to the point of being considered one of those symbols of democracy which, along with museums, universities, and monuments, any advanced city in the West had to have. Then globalization upended the model, and did so in two ways: on the one hand by challenging the idea of ‘national’ culture, and on the other by opening the hitherto exclusive catalog of large libraries to emerging countries, which saw this type of architecture as an emblem of the new international status they were acquiring or aspiring to acquire. All this in the context of increasing digitalization, which impacted on the symbolism and social use of libraries less than it affected its primary function, containing books, in view of the fact that huge digital archives – accessible through the cloud and hence de-materialized – are presumptively making libraries redundant: mere showrooms for books whose contents are now available in a different form, bodyless, open to all.

This paradigm shift, which we have been taking stock of in these pages for almost fifteen years (see Arquitectura Viva 135), explains the rationale of many of the libraries that have gone up in the world since globalization took root as a reality. On the one hand, as agoras for social exchange, they serve a status purpose, making the book less a thing for building knowledge than one for building prestige. On the other, they serve as international magnets, commissioned to star architects to reinforce a country’s cultural image.

Such is precisely the case of the two examples detailed in this dossier: the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, and the Beijing City Library. The first, the fruit of an international competition won by the Swiss partnership of Herzog & de Meuron, rises with natural grace in the biblical capital, connecting with the material culture and the climate of the place while providing a welcoming space whose atmosphere is determined by the physical presence of books, as in ancient libraries. For its part, the library located in the Beijing district of Tongzhou, a work of the Norwegian firm Snøhetta, transforms books into an ornamental motif by means of a topography of long curving shelves and a forest of columns, resulting in an indoor landscape conceived less as a silent haven for reading than as a small city in and of itself: a space meant for social interaction.

Sou Fujimoto Architects, Biblioteca de la Escuela de Arte de Musashino, Tokio (Japón)