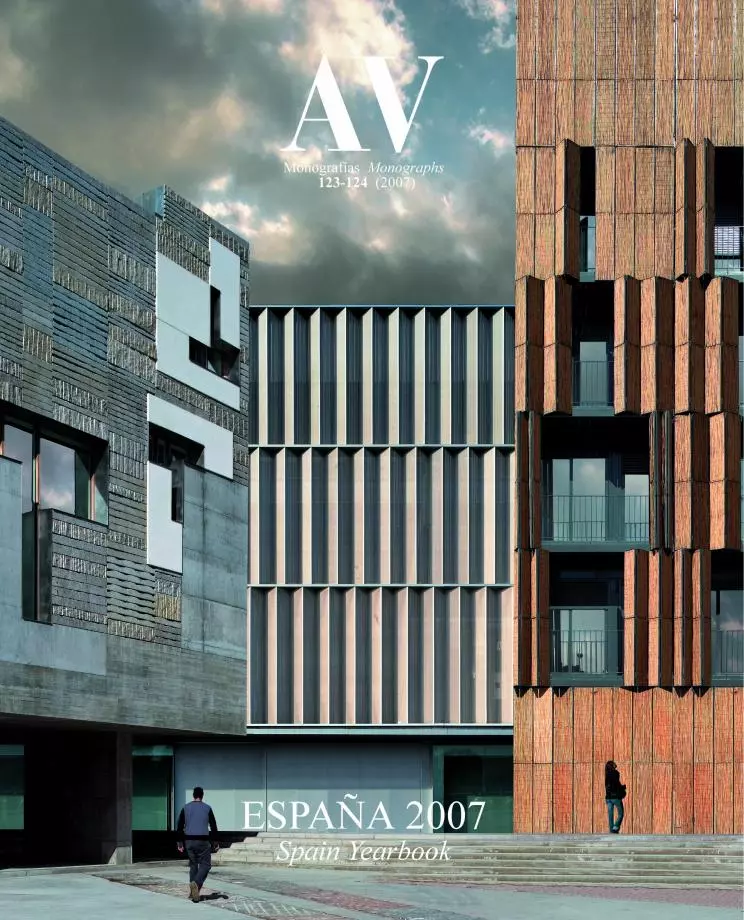

Motor Works

The old romance between architecture and the car has been rekindled with landmark buildings by Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster or Ben van Berkel.

Modern architecture and the automobile were born at the same time, and they may well disappear together. Both shaped the 20th century, and both are to a fair extent responsible for the consumption of fossil fuels that has given rise to the insomniac territory of an accelerated time. Oil nourishes engines, but also buildings, and in the end our model of a city is rendered unsustainable as much by energy use in transport as it is by energy use in construction. Of course urban development of the disperse kind based on the automobile is the main link between architecture and energy; but buildings,too, require the consumption of non-renewable resources, not only in their construction but also in their maintenance, and this puts architects in the same frame of mind as manufacturers of vehicles. Although on their own they can do little to modify territorial models, they can do much to construct buildings and fabricate automobiles that consume less energy, a worthy goal that appears prominently in the press releases of professional associations and the commercials of car brands. But while architects’ congresses and motor trade fairs preach on sustainability, ecological construction, and hybrid vehicles, the building and automobile sectors celebrate their old friendship with a handful of spectacular structures where intentions to make amends are subordinated to a desire to surprise, pedagogy to emotion, and calculation to impact.

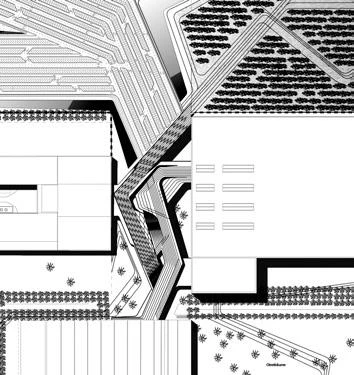

In the BMW building in Leipzig, Hadid organizes the program in ribbons entagled amid hangars.

EIn his famous book-manifesto of 1923, Toward a New Architecture, Le Corbusier compared the evolution of Greek temples to that of automobiles. Such fascination with the mechanic world made him the main propagandist both of the city at the service of traffic and of architecture inspired by the procedures of industry: two vectors of innovation underlying his titanic (and fortunately never carried out) Voisin Plan for Paris, named after the car manufacturer Gabriel Voisin, as it does the significantly named Maison Citroan. This coming together of construction and automobile was more symbolic than material, and it can be said that the marriage between them was really consummated in the anonymous sheds that Albert Kahn built for Ford, factories that were of such pure functionality that Stalin himself did not hesitate to summon Kahn for the building of a large number of like structures in the Soviet Union, or in the mythical work of Lingotto, where the engineer Giacomo Mattè-Trucco crowned his factory for Fiat, remodeled in the past decade by Renzo Piano, with a test track for cars.In any case Le Corbusier’s flirtations with the automobile, just like Melnikov’s alluring Parisian garage projects of the same years, marked a publicity romance of evident efficacy for both parts, one that lives on to our days. In the interwar period, the master photographed his Villa Stein with an automobile in the foreground, while the firm Daimler-Benz announced its 8/38 Mercedes-Benz with an image of it in front of Le Corbusier’s building in the Weissenhof of Stuttgart. Today, the latest car models are routinely advertised against a background of new architecture, as are high-fashion collections, and in turn the major manufacturers of automobiles take pains to complement their endless production hangars with symbolic gestures entrusted to architectural celebrities, and sometimes they turn to this Formula 1 of the profession even for their research and communication premises.

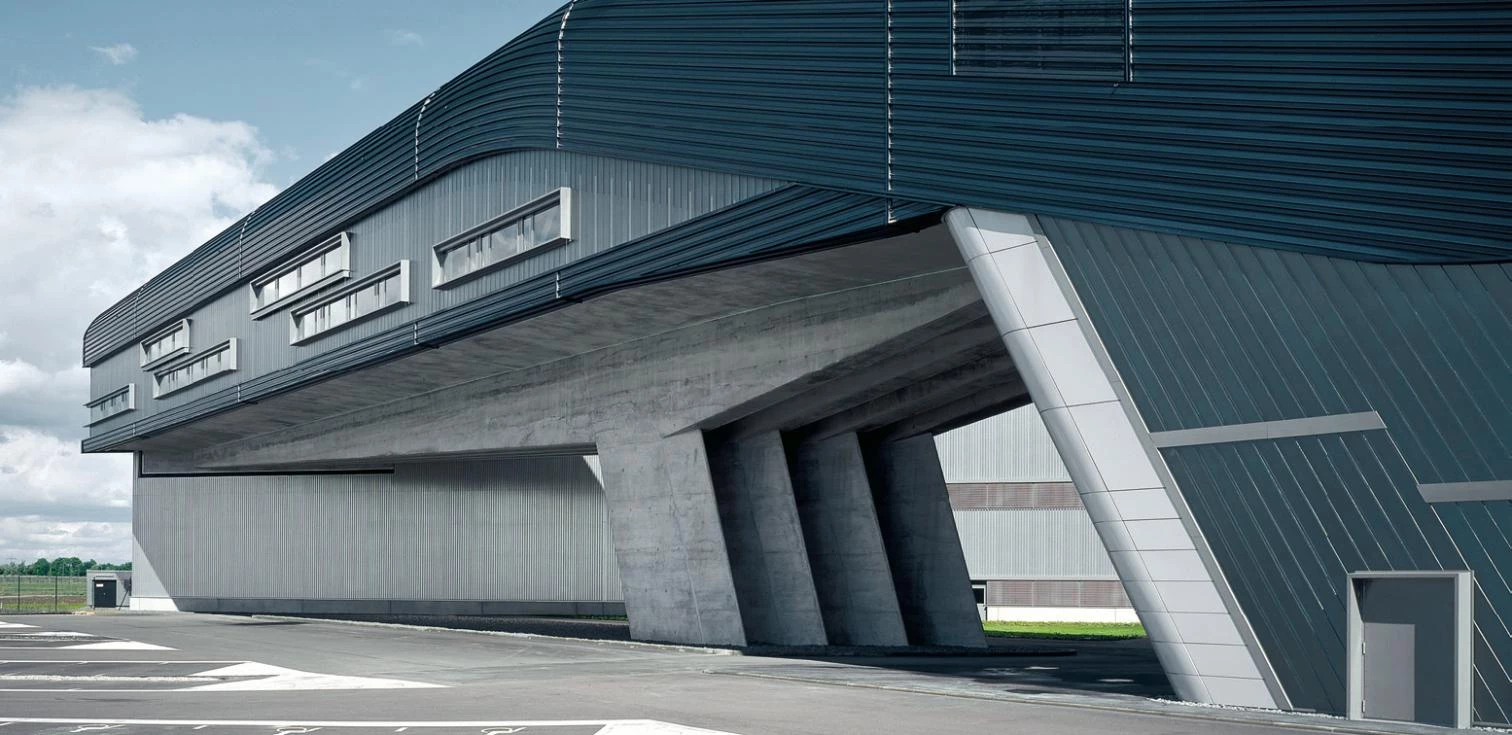

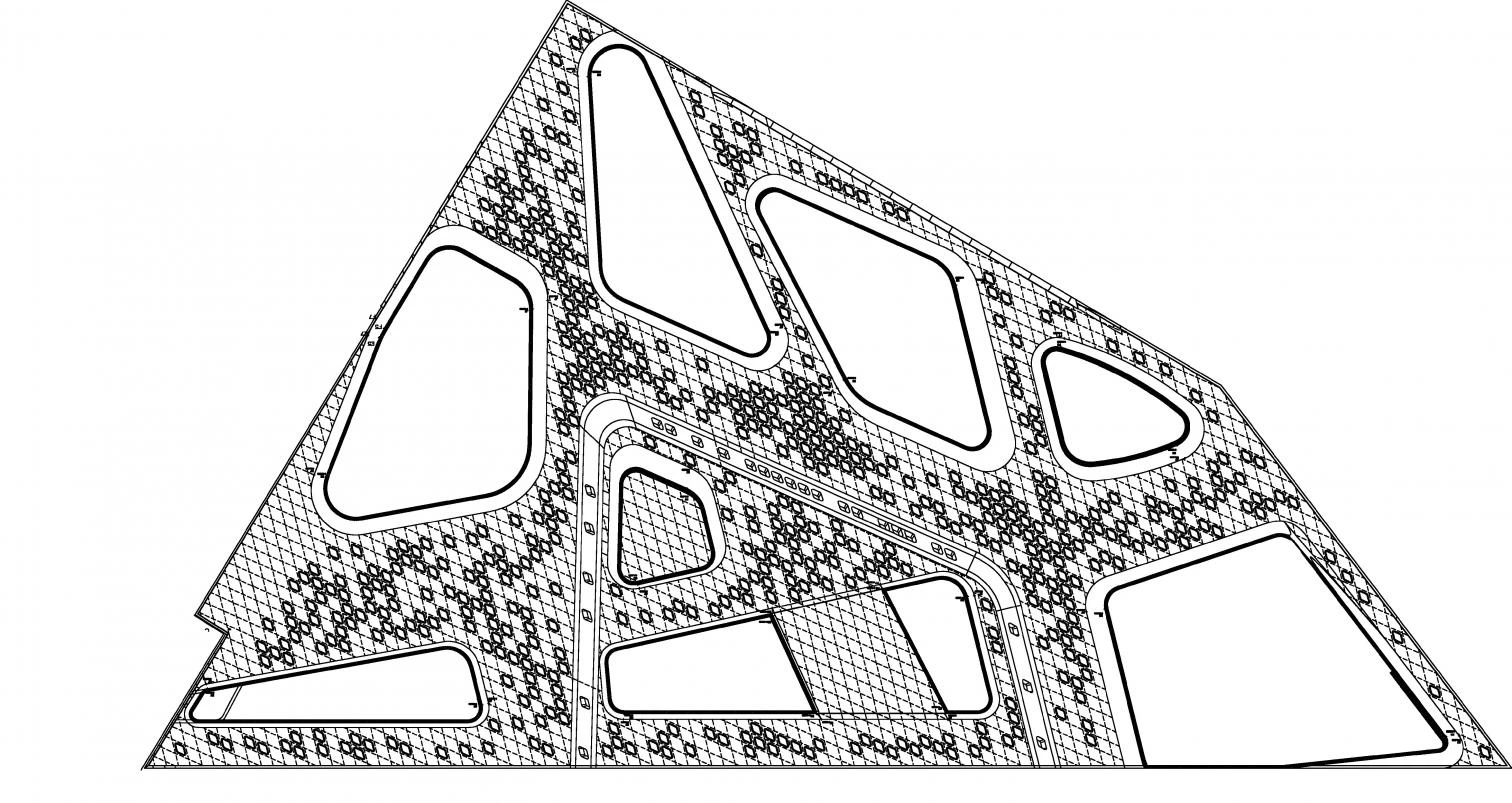

The sculptural, dynamic forms of Zaha Hadid, shaped with concrete, quite effectively evoke the speed of automobiles, as shown in works like the iconic Science Center next to the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg.

Good examples of the first variant are Zaha Hadid’s latest projects, BMW’s building in Leipzig and the Science Center in the Volkswagen city of Wolfsburg, as well as the automobile museum that Ben van Berkel has almost finished for Mercedes-Benz in Stuttgart. Illustrating the second option are the research centers of McLaren and Ferrari, works by Norman Foster and Massimiliano Fuksas, or Renault’s Communication Center, built by Jakob & MacFarlane in obsolete industrial sheds. The Anglo-Iraqi’s works for the German brands both use self-compactable concrete, a technique without which we could not possibly imagine their oneiric forms being materialized, but in every other sense they are almost diametrically opposed. BMW’s factory in Leipzig places offices, laboratories and the canteen in a Piranesian hank of galleries and platforms which are overflown by ribbons that silently drag the bodyworks of the cars, and which tangle up tightly between three huge production hangars, constructing the piece like a hinge that also serves as an entrance and a showroom for the firm, complete with a souvenir shop. For its part, beside Volkswagen’s factory in Wolfsburg, the formidable Science Center is a sculptural free-standing volume that lifts up on pachyderm legs a refined landscape of warped concrete, which serves as a support for the randomly placed experiment stations that aim to spread scientific knowledge while entertaining in the manner of an amusement park. Also meant for exhibition purposes, and also free-standing and sculptural, is the museum created for Mercedes-Benz in Stuttgart by the UNStudio of the Dutch Ben van Berkel, whose passion for the Moebius Strip comes across here through a clover of warped leaves that is transformed into a spiral ramp vaguely evocative of Wright’s Guggenheim, but interpreted with spaces that flow in a double helix so that the spectator sliding down from above threads the history of the automobile with that of the company itself.

More sober are the spaces conceived for re-search and development, such as the exquisite McLaren Technological Center built by Norman Foster in Woking, a slice of glass and steel whose sinuous outline surrounds an artificial lake so as to trace a perfect circle in the bucolic context of the English countryside; or the Research Center of Ferrari, raised by Massimiliano Fuksas in Maranello with three volumes of extreme horizontality and lightness that are piled up weightlessly in the vicinity of the factory. In contrast, the Communication Center of Renault reuses the industrial sheds built by Claude Vasconi in the eighties – the last remains of the huge plant at Boulogne-Billancourt, in the outskirts of Paris, before production was altogether decentralized – and fits them out to accommodate the company’s creative advertising staff and sales machinery. For this Jakob & MacFarlane come up with an informal environment of exposed services and folded planes imbued with a certain taste of origami-like Californian deconstruction.

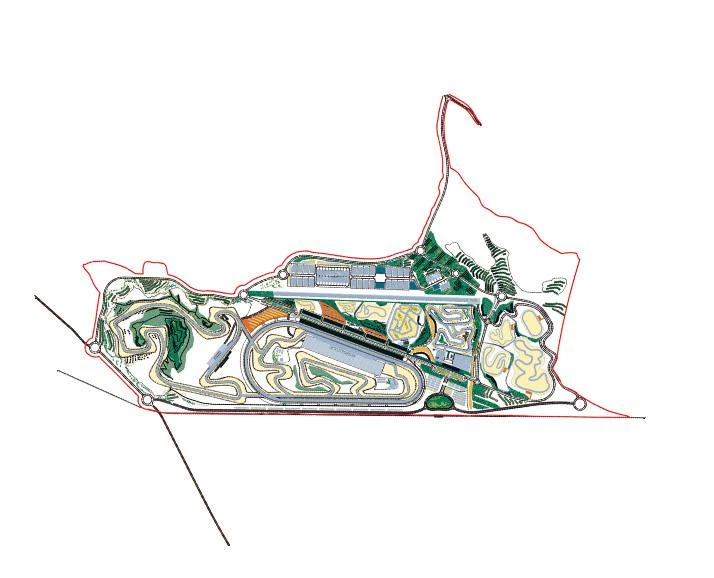

Spain has its own motor tradition, brought of late to paroxysmal levels by ‘Alonsomania’, and is no stranger to this blooming of automobile architectures. Proof of this are two projects recently set in motion in Alcañiz and Torrejón de la Calzada. The town of the province of Teruel is witnessing the birth of a Motor City, a colossal complex complete with racing tracks, a technological park, and leisure facilities promoted by the regional government of Aragón, which presented it in Madrid through its vice-president, José Ángel Biel, the car race driver Pedro Martínez de la Rosa and the racing track designer Hermann Tilke. And the municipality of the province of Madrid, in turn, is building a spectacular Museum of the Automotive. Conceived by Mariluz Barreiros, daughter of the entrepreneur who set up the motor industry in Spain and Cuba, it is designed by the office of Mansilla & Tuñón as a huge cylinder materialized with pressed cars that allude as much to the recycling park it is part of, the La Torre Technical Assistance Center, as to the necessary ecological consciousness-raising in re-use and sustainability that nowadays inspires both the world of architecture and the world of the motor vehicle. Coinciding with the Universal Exposition of Aichi, the firm Toyota presented – somehow in the manner of ‘concept cars’ – an “intelligent and sustainable house” developed by its various research departments which incorporated over a hundred patents. The result was aesthetically poor and sociologically extravagant – a 700-meter house for the country that invented the capsule-hotel. But it is also a revealing example of the by now centenary romance between modern architecture and the automobile: a seductive and fertile relationship that in our own times is conceivable only if placed at the service of environmental responsibility.

The car plays the lead in the Technology Center of Foster for McLaren and the museum of Van Berkel for Mercedes-Benz, as well as in the projects of the Ciudad del Motor and the Museo de Automoción.