Relatively few architects have solved the challenge of giving physical expression to the desire for a legacy. Of course any architect’s oeuvre is itself a physical expression of his or her legacy, and for most, the built work that they leave behind will always be of primary importance. But still, what of all the drawings and models, of all the images and all the correspondence and other documents that trace the stories behind the work that the forms themselves cannot reveal? And what of the records of projects that were never built, projects that can sometimes be as important to an oeuvre as the ones that were realized? The preservation of the documents of unbuilt projects can be even more critical. And all of these objects hold the potential of even deeper resonance if they can be housed in a meaningful space of the architect’s own design. This does not happen often. Le Corbusier’s archives are stored at the Fondation Le Corbusier, in the Maison La Roche, in Paris, but that is one of the rare occasions in which an architect’s records are housed within a building he created, in the city in which he based his practice. The archives of most other architects of note reside at libraries or universities or museums, preserved respectfully as cultural treasures but in environments that can hardly be called unique to their subjects.

Norman Foster sought something different, more along the lines of the Fondation Le Corbusier, when he began to plan for a foundation to preserve his archives. He was motivated by more than the desire to house his drawings and models in a space of his own design, although he hoped to make that a part of his plan; he also envisioned that his foundation would have a broader program than that of accommodating scholarly research into his own work. Foster wanted it also to serve as a center for broader research on the topics that have motivated him throughout his career – the history of modernity, the challenges of urbanism, the relationship of engineering to architecture, the issues of sustainability, all of which excite him personally and serve as touchstones for his pracitice. Foster’s first foray into architectural philanthropy came after he won the Pritzker Prize in 1999, after which he set up a foundation with the limited mission of underwriting travel and study opportunities for young architects and students. Now he wanted to broaden his ambitions, and continue that program and fold it into the broader mission of supporting the legacy of research and inquiry that has always motivated his practice.

So what Foster had in mind was one part think tank, one part library and archive, one part Norman Foster museum. The latter is the least exciting to him, at least standing on its own; while Foster possesses an extraordinary collection of iconic pieces of modern design, including one of the most notable modern automotive collections in existence, he likes to think of these objects as stimuli for fresh thought, not as mere objects on pedestals. If any of them were to be displayed, it was important to him that it be in the context of an institution that would exist to look forward as well as backward – whose very being, in fact, would underscore the notion that we preserve not to fetishize, but to inspire. Whether it is a model of Foster’s Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, a sketch of the Reichstag, or the actual Voisin automobile of Le Corbusier that Foster rediscovered, purchased, and restored, Foster wanted to gather them together in the belief that they can teach us something that will help us make the future better.

Foster’s vision for his foundation required a freestanding institution, independent and capable of supporting storage, conservation, and display as well as hosting symposia and other events. He said that he considered locating the foundation in either a major city such as New York, Berlin, or London, the base of his practice, or, mindful of the appeal of very different kinds of non-urban institutions like the Donald Judd Foundation in Marfa, Texas, in some other such isolated rural outpost. Ultimately he decided on Madrid, in part because of his own close ties to the city since his marriage in 1996 to Elena Ochoa, but also, one suspects, because he has focused so much of his creative energy in the last half century on the question of the urban future that it would seem unnatural, almost discordant, for his foundation not to be based in a major, cosmopolitan city.

Building with History

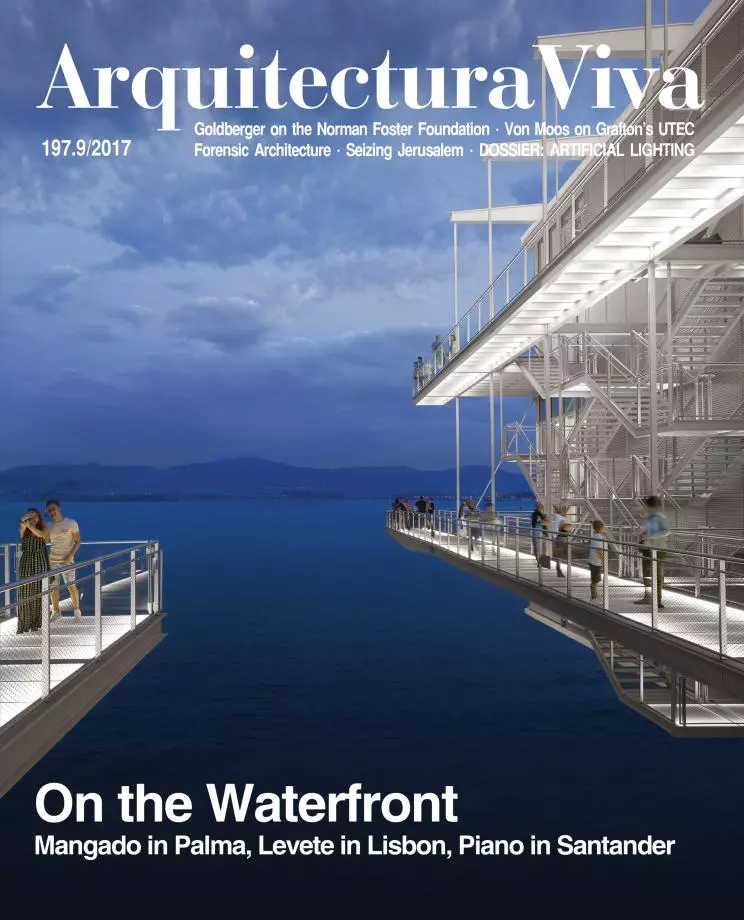

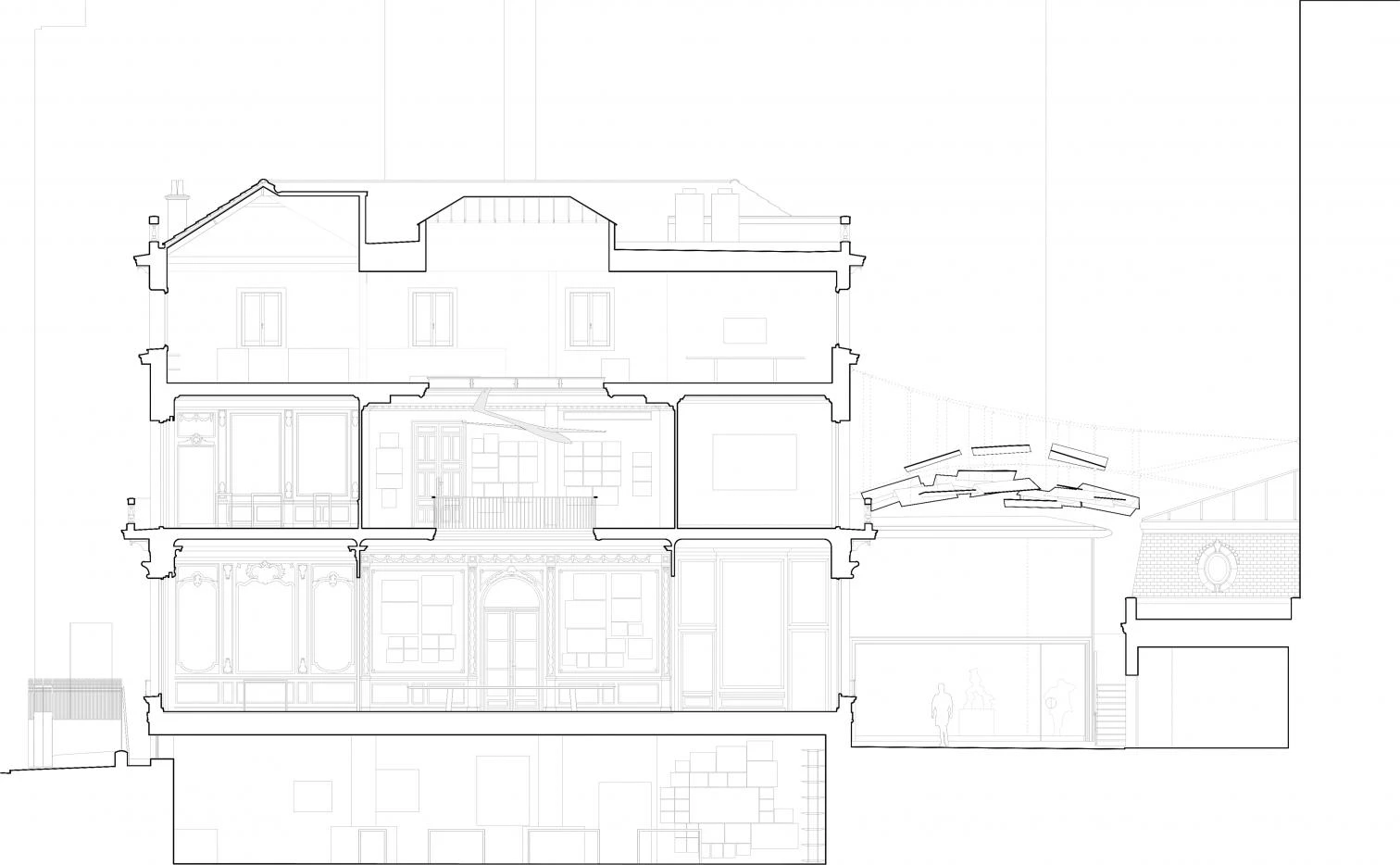

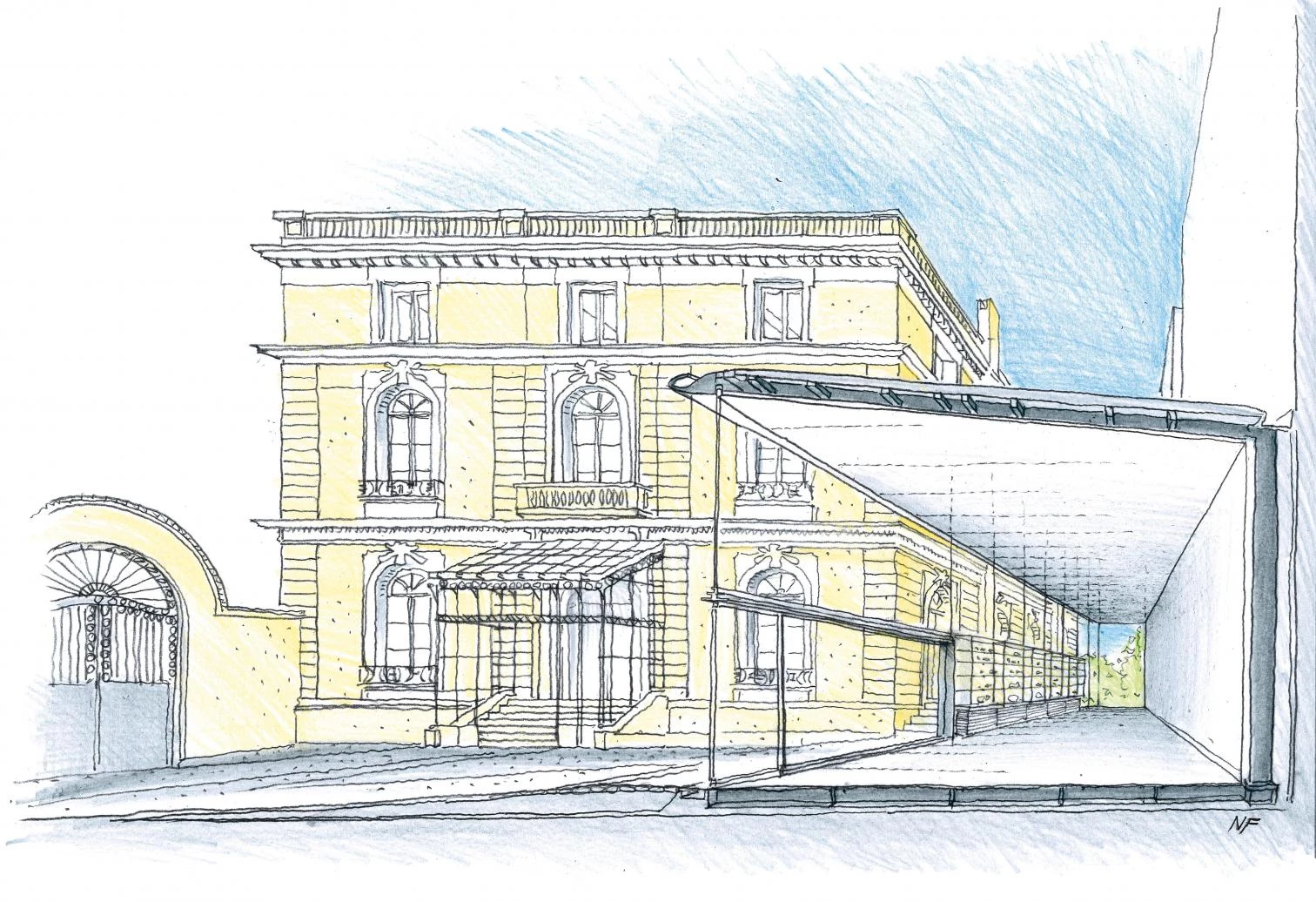

A third reason for the decision to locate the Norman Foster Foundation in Madrid was the availability of an exceptionally suitable building: a magnificent Beaux Arts palace in one of the city’s most attractive quarters, built in 1914 and used for many years as the Turkish Embassy and later as the headquarters for a Spanish bank. Not the least of the reasons that the house, designed by the architect Joaquin Saldaña as a residence for the Duke of Plasencia, was notable was that it faced a large, private courtyard that was ideal for the addition of a modern exhibition and meeting pavilion. That expansion offered more than additional square footage for the Foundation’s program: it also allowed the project to demonstrate the aesthetic potential of placing a modernist annex in counterpoint to the historical building, tying Madrid to the many works of Foster + Partners around the world over the last generation that have explored the notion of formal and stylistic juxtaposition and have made the mixture of old and new a significant theme of the practice’s work.

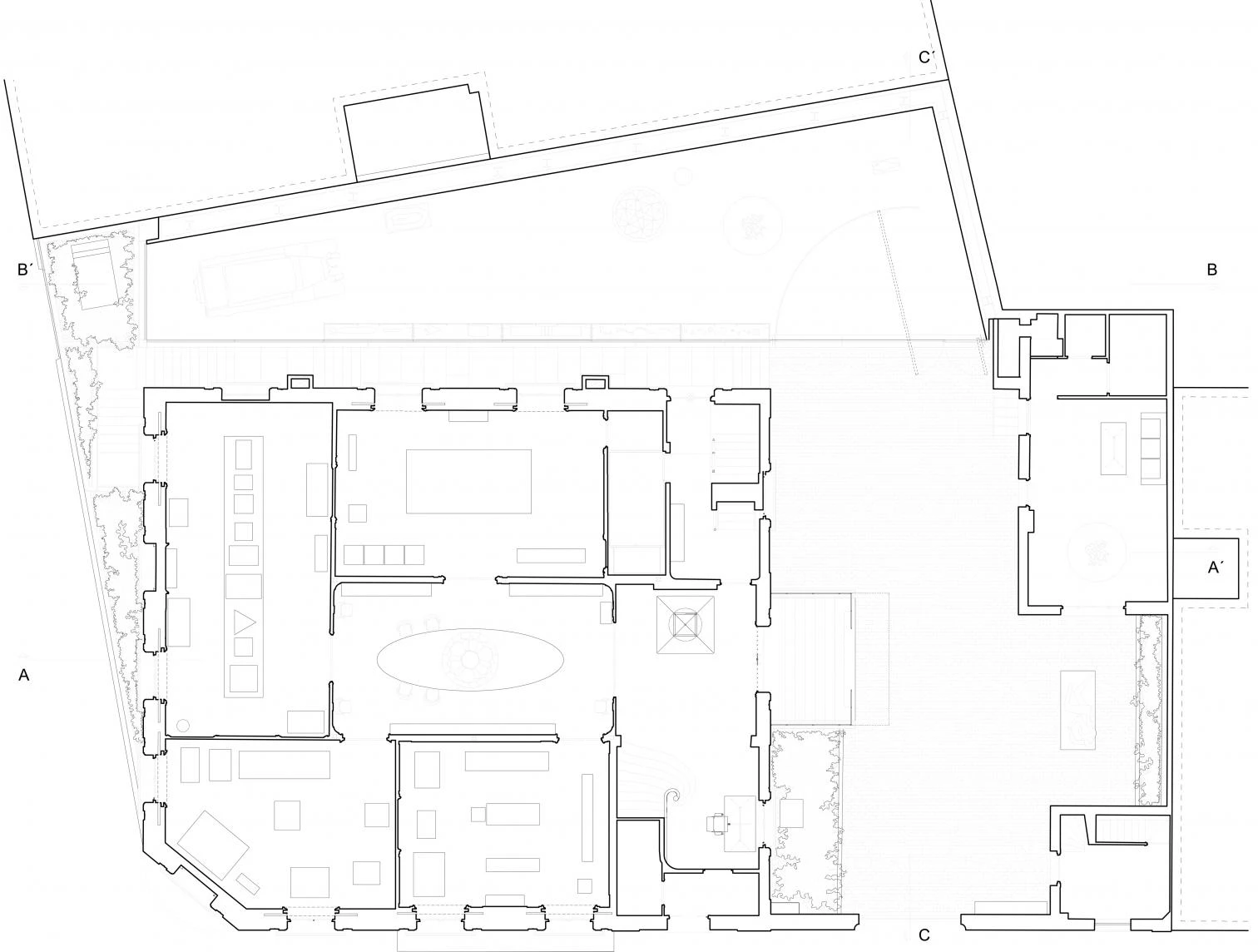

As in many of the other Foster projects in the category the practice refers to as ‘building with history,’ the original building, meticulously restored, remains the core of the project. The palace is grandly scaled, with three major floors above grade and a large, open lower level. The exterior was restored with minimal changes to its original appearance, including an elegant glass-canopied main entry from the courtyard, and the floor plan of the interior, with multiple rooms, all of grand but domestic scale, was retained on the three main levels. The ornate interior architectural detailing has been refurbished, and in combination with new lighting and white walls the effect is of sleek, modern spaces set within a traditional shell, each room, in effect, replicating in miniature the interplay between old and new that the entire project represents – an interplay that is intensified by the array of models and drawings of Foster + Partners buildings that are on display in the major rooms.

The main floors of the palace built by Joaquín Saldaña in 1914 will be used as galleries for exhibiting models and drawings; the basement contains archives, more models, and workspaces for researchers.

Foster’s work represents an aesthetic that, for all its obvious differences from that of the palace itself, nevertheless seems at home in these rooms. The models and drawings possess an inherent visual richness, and Foster’s respect for surface and texture, consistent reference to human scale, and ever-present sense of urbanity all make for what might be called a benign and relaxed discourse between his crisply modern work and the traditional spaces in which it is displayed.

These main rooms are set up as galleries but can also be used as meeting, seminar, and lecture spaces. As if to make clear from the moment of arrival that the building is intended as far more than a storehouse and display center, the central hall of the main floor has as its centerpiece not one of the architect’s models but an elliptical meeting table of Foster’s design: the message is that exchange of ideas takes precedence over viewing and admiring the work of the past, even though Foster’s archives are the ballast, so to speak, of the Foundation. The sense of workspace continues on the lower level, which has been reconfigured into a large, open work and display space, with multiple work stations for researchers as well as a large library and additional areas to show models. In good weather, programs and events can also spread out into the courtyard, which is fully private and invisible from the street.

Influences without Stress

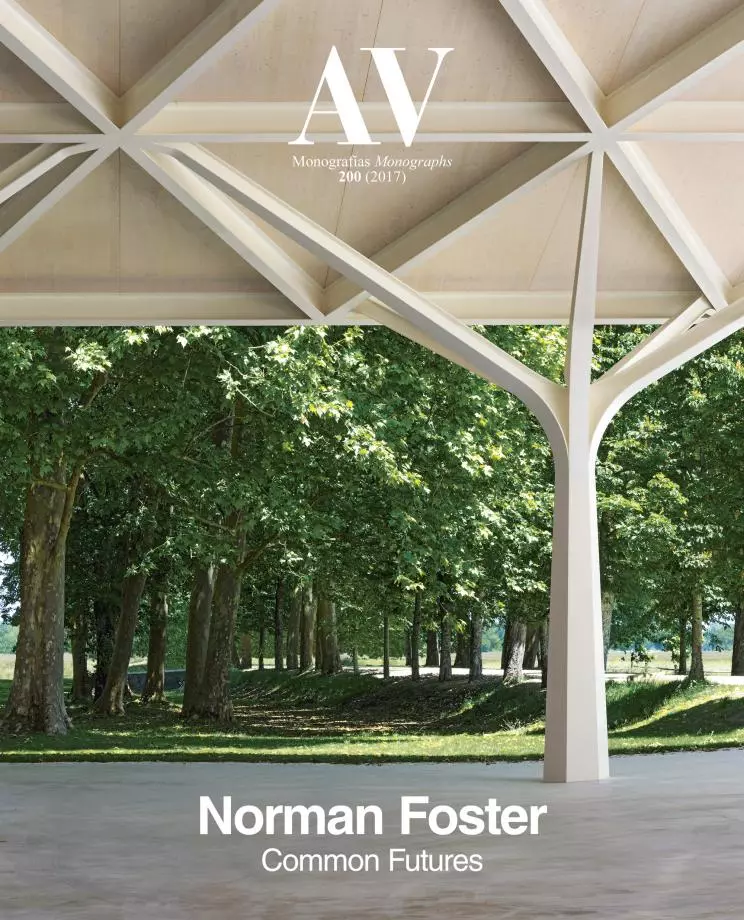

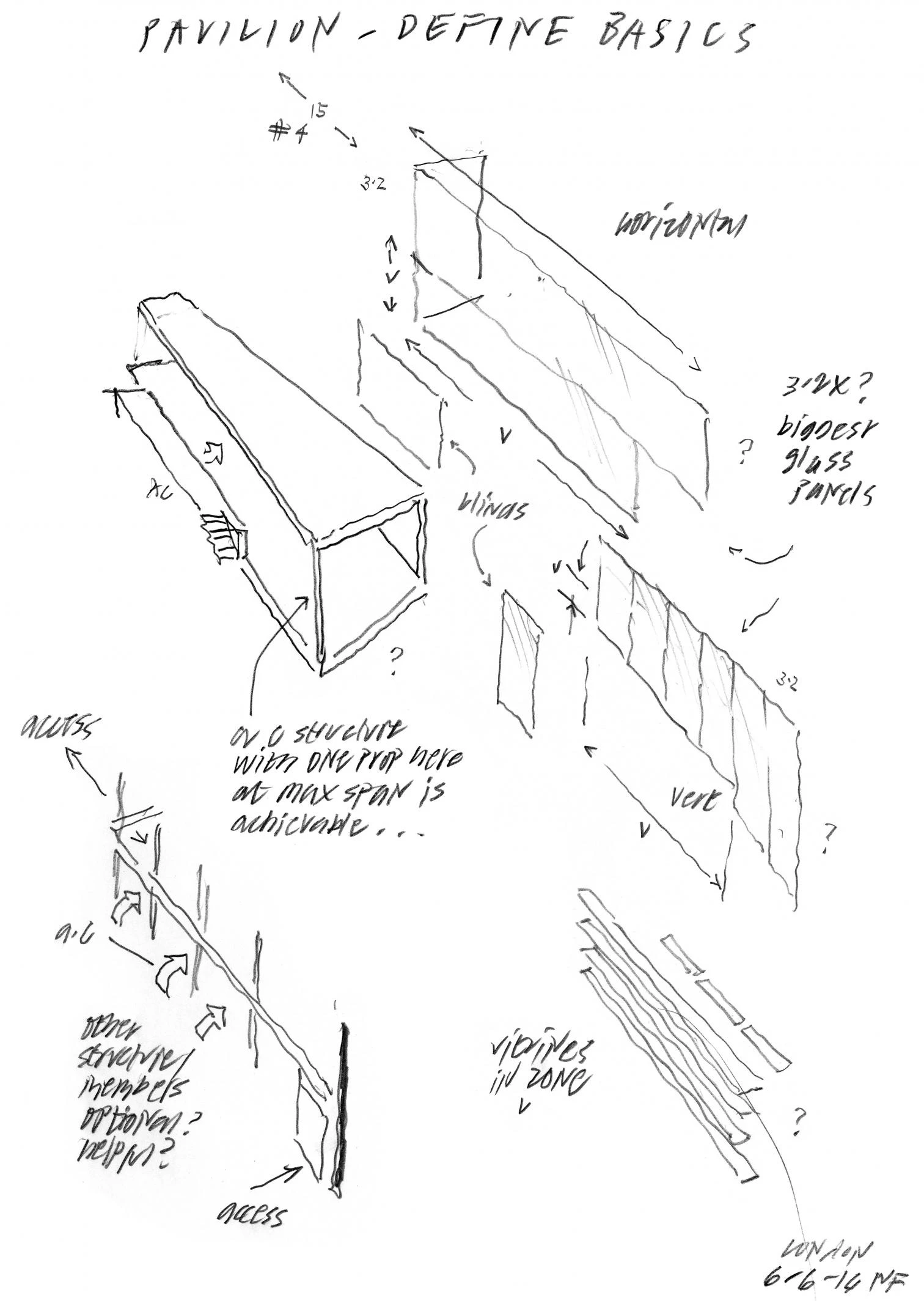

Tucked beside the palace, and extending out beyond it to form one side of the courtyard, is what Foster has called the ‘Pavilion of Inspirations,’ the glass addition, its entrance marked by a metallic canopy by the Spanish sculptor Cristina Iglesias that serves as a transition between the old metal and glass canopy of the palace and Foster’s new structure of glass. Like so much of Foster’s work, the pavilion exploits technology in the service of a pristine and elegant aesthetic, and the result is minimalism elevated to true sensuousness. The enormous glass walls appear to support the entire pavilion, and one section swings out like a vast door, wide enough for a vehicle to enter. (The pavilion could actually contain more than one of the cars from Foster’s collection, although only the Voisin was put on display for the opening.) One of the glass walls contains glass shelving on which are shown more of Foster’s ‘inspirations,’ to underscore once again the notion that every one of the Foundation spaces is intended for meeting and discussion, not just for admiration of Fosteriana.

Still, the glass pavilion is a kind of museum of design in miniature, a curated gallery of highlights from Foster’s various collections. But its most important role is as a piece of architecture, as it should be. Like so much of Foster’s work it is a graceful composition, and visually so light it appears as if it could float off the ground. It is anchored by the intellectual and emotional gravitas it projects, gravitas sufficient to allow it to hold its own beside the noble and heavy stone palace to which it has been appended. In this way the glass pavilion joins so much of Foster’s oeuvre as it presents a message of balance, and of the coexistence of objects that are dramatically different and yet complement each other. Out of this architectural synthesis comes a new kind of whole, dependent on establishing a productive connection between the best of the new and the celebration of architectural heritage: a goal that describes not only much of Norman Foster’s work, but the mission of the foundation that the British architect has just inaugurated in Madrid.

Paul Goldberger, architectural historian and critic of The New York Times, is a winner of the Pulitzer Prize.