More Towers and More Walls

Five years afer 9-11, the decline of the skyscraper has not happened, and the world sees the proliferation of both towers and walls between people or ideas.

The Chicago skyline with the tower designed by Calatrava; opposite, Shanghai with the ‘opener’ skyscraper by KPF and, below, a view of the Burj Dubai, which will be the world’s tallest building, in progress.

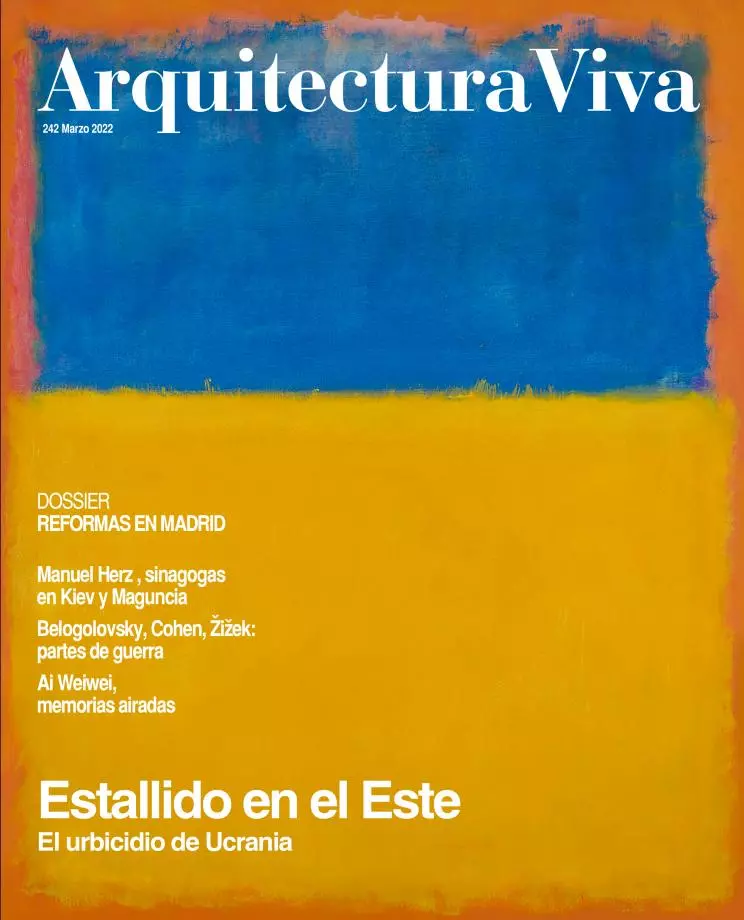

The 20th century ended in Berlin, but the 21st began in New York. The cold war between ideologies came to a close with the coming down of the wall, and the hot war between civilizations broke out with the collapsing of the two towers. Five years after 9-11, the prediction concerning the death of the skyscraper has proven as erroneous as the previous one about the disappearance of the walls that divide the planet. Technical and symbolic globalization continues to raise high-rises that send out an overbearing and optimistic message, while at ground level the world crackles with innumerable boundary fences and computer fire walls that try to block the passage of persons and ideas.

For Chicago, the cradle of skyscrapers, Santiago Calatrava is designing what will be the tallest in the United States, while the federal administration seals the Mexican border with wire fences, pits, and heat sensors. In Shanghai, where cranes and towers abound like nowhere, the completion of the World Financial Center by the American firm Kohn Pedersen Fox will give the city the height record heretofore held by Kuala Lumpur and Taipei, while the Chinese government censors Google and Yahoo and blocks access to the Wikipedia with cybernetic barriers. And in Dubai, in the troubled Middle East that gave birth to the world’s first cities, the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill plans to beat Shanghai with an even taller skyscraper, shifting the planet’s ceiling to the Persian Gulf, without such an achievement of the global economy preventing boundary walls between rich and poor from going up in the region, whether between Saudi Arabia and Yemen or between Israel and Palestine. Not even in Spain’s periphery is the proliferation of towers in the big cities and tourist havens – from Nouvel’s polychromatic shell in Barcelona to the four skyscrapers rising on Madrid’s Paseo de la Castellana, passing through the many building developments going on along the Mediterranean coast and the Canarian archipelago – incompatible with the closing up of southern frontiers through radars in the Strait of Gibraltar, fences around Ceuta and Melilla, and patrol boats in the Atlantic Ocean, all under siege by the misery of Africa.

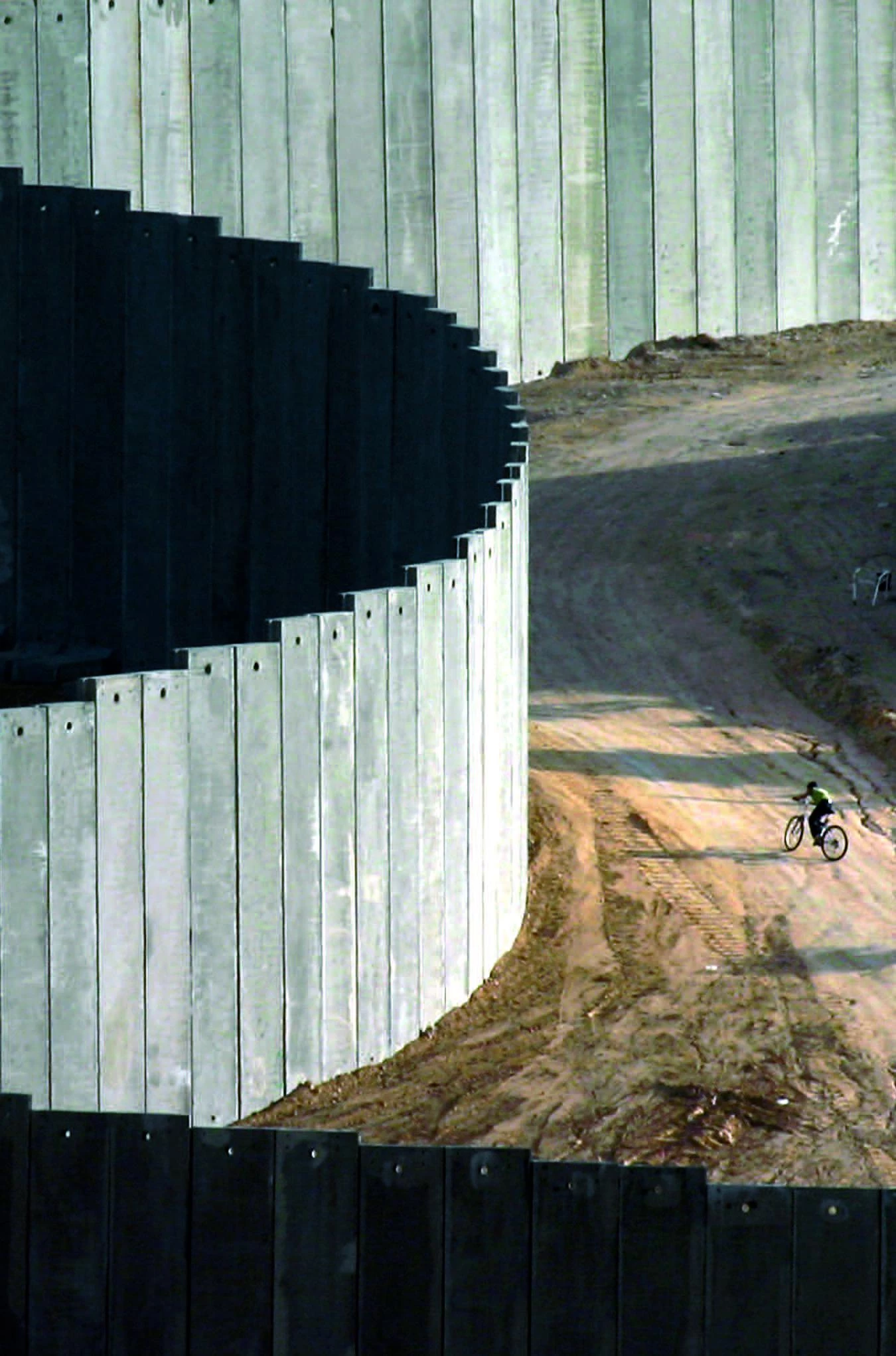

Berlin was not the last wall, nor did the attacks against the World Trade Center Twin Towers bring about the end of skyscrapers. In the wake of 9-11, it seemed that skyscrapers were giants with feet of mud, but maybe their vulnerability was not so much technical as social, and the safety of these emblems of political and economic power is more threatened by the multiplication of barriers that fracture the territory, segregate populations, and nourish resentment than by the risks associated with their structural daring and complexity. The suicide cells of September 11 were under the command of Mohamed Atta, who had gone to the Arab world’s oldest architecture school, in Cairo (as had Hassan Fathy, Egypt’s leading architect, an advocate of neo-vernacular construction at the service of the poor, against western modernity), and gone on to earn a degree in urban planning from Hamburg’s TUHH – a young polytechnic university whose dean of urban planning, Dittmar Machule, a defender of traditional schemes, had taken part in refurbishing the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo –with a thesis on the conflict between Islamic town planning and modernity. This makes one wonder if the objective of the terrorist attack may have been not only political, but also architectural. A similar conclusion can be extracted from Eyal Weizman’s analysis of the politician Ariel Sharon as an architect, when the writer explores the geometry of the occupation of the West Bank from the viewpoint of the intersection of power, security, and urbanism, showing to what extent military strategy, the geopolitics of protection, and the architecture of territories are inseparable.

The wall between Israel and the Palestinian West Bank has become a symbol of all the frontiers that tear the planet, bringing misery and pain to those excluded without giving security to those seeking shelter behind them.

Five years after 9-11, the catastrophic clash of the skyscraper and the airplane has rendered high-rise construction more costly, and commercial aviation more troublesome. But the expansive wave of the event has done more harm on the ground than on the sky, and the chain of Islamist bombs that has opened cracks of panic from Madrid to Bali has shaken the architecture of globalization less than the discredit that a bellicose empire has brought upon itself. This empire has proven itself as impotent in guaranteeing security and establishing democracy in Muslim countries as it has shown it-self incapable of filling the tragic void of Ground Zero – bogged down as it is in a marasmus that is more real estate-related than civic – with an architectural sign of confidence and hope. On the other side of the Atlantic, London was able to replace the Baltic Exchange, a building destroyed by the IRA, with a light and luminous tower, designed and built by Norman Foster for the insurance firm Swiss Re, that soars above the skyline of the City like a peaceful projectile: if the West wants to propose an icon of encounter and healing for the trauma of horror, this at once swift and blunt skyscraper would be a good candidate indeed.

Meanwhile we will continue to look upon the devastation of Lebanon as a titanic but poor imitation of the deconstructions of Gordon Matta-Clark, the civil war of Iraq as a conflict existing only on screens impassively broadcasting the umpteenth explosion, and Iran’s threatening determination to create an Islamic atomic bomb as a mere diplomatic game, all in the course of this uncanny August that has seen Spaniards sequestered by the cruel summer of 1936, Germans from Günter Grass to Arno Breker sequestered by their ominous past, and Cubans sequestered by a Fidel Castro who pathetically sequesters himself, clutching a newspaper as proof of life. But maybe T.S. Eliot was right, and the world ends not with a bang but a whimper: not with an explosion, but with a moan.

Israeli wall in the West Bank