Overseas in October

Aquick architectural tour of North America gives some impressions of recent works as well as observations on the cultural and political climate across the Atlantic.

I am a suspect. In the course of this fleeting American week I have twice received the four S’s that lead to a particularly rigorous check. From New York to San Francisco, chance or the slightest possibility of danger marks travel documents with the ominous SSSS that only a handful of bloggers claim to know how to decipher, and the passenger meekly surrenders himself to a humiliating scrutiny of clothes and luggage in search of signs of explosives or drugs, and an interminable examination and frisking where jokes can be a ground for a penal process. Compared to the unanimous and amiable supervision of immigration agents, the arbitrary opacity of the Homeland Security reveals the extent of the territories that freedom is ceding to fear. It is my third visit to the United States in a year, and I embark on each trip with increased reluctance.

If the Prada flagship store in Los Angeles surpasses the one built also by Rem Koolhaas in New York, the New de Young Museum in San Francisco is one of the best works by Herzog & de Meuron

Monday in L.A. dawns with a fog that soon dissolves, and the din of the traffic on the freeways silences the mediatic explosion of the weekend fires, by now just traces of smoke in the distance. On Sunday Eric Owen Moss showed me around his Culver City complex, a fractured suburban utopia of pragmatic sculptural sheds, and I also visited the Prada store on Rodeo Drive, a Rem Koolhaas work that is much less publicized than its sister in New York City’s Soho, but that is is better resolved because of the way its routes tangle up with the large staggered wave, more sensual because of the spongy or translucent quality of its exact materials, and more seductive thanks to the maze of galleries that form subterranean shop windows beneath the sidewalks. This first working day of the week I once again pass through Bunker Hill, a hub of civic life regenerated by cultural buildings and the conversion of offices into residential lofts, but also besieged by a somber army of 80,000 homeless people who camp along the edges, drawn to California’s benign climate by the closing of psychiatric institutions and the break-up of families. In this city of contrasts, Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall raises its beautiful flower of steel on Grand Avenue. Its raised picturesque garden and theatrical entrance spill onto the street, faking an urbanity that is ironically subverted by the interior cascade of stairs channelling the flow of spectators toward the innumerable parking basements. Just a block away, Rafael Moneo’s fortress of a cathedral defines its perimeter, which is marked by the categorical bell tower; inside, the herringbone pattern of the ceilings and the concrete cross over the alabaster are delicate, but the access is somewhat confusing, the building looks characterless from the bordering freeway, and the interior has been disfigured by the proliferation of deplorable imagery, a testimony of the dull sensibility of Cardinal Mahoney, to whom I suppose we must also attribute the atrocious funerary crypt that has Gregory Peck as most famous tenant. And the Caltrans building of Morphosis colonizes the foot of the hill with distracted energy and catastrophic decorations that waver between a titanic reference to the Russian constructivists and a tribute malgré soi to the industrial ready-made or the roadside bricolage. My afternoon conference takes place in the SCI-Arc shed, a factory space that brings together professors who have gone from manufactured deconstruction to computerized organicism with students all but exhausted from the formal exacerbation of this exuberant expressionism nourished by both prosperity and climate.

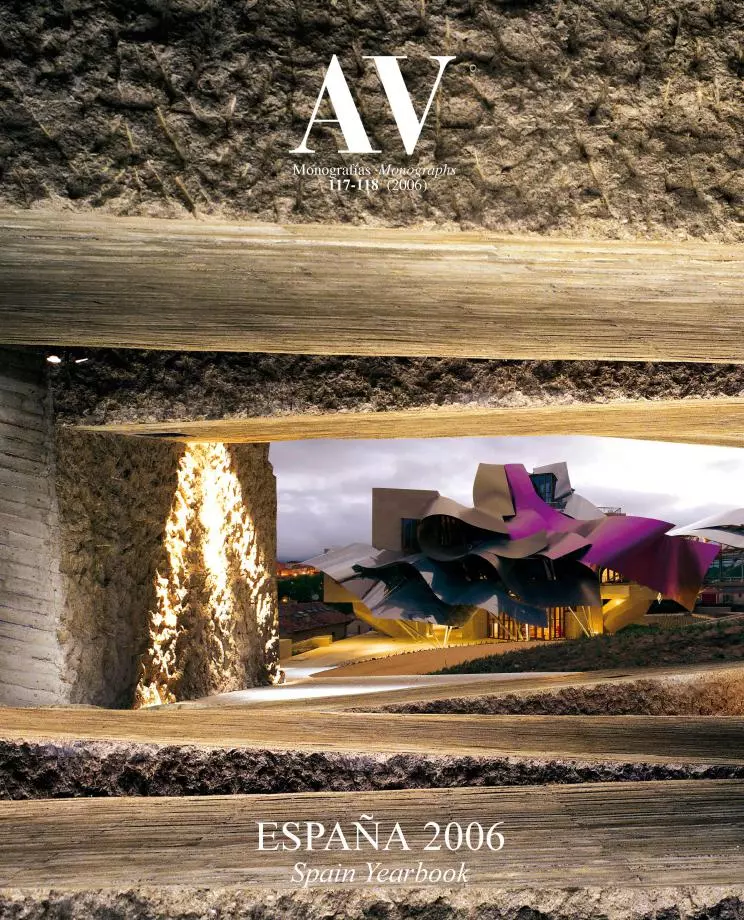

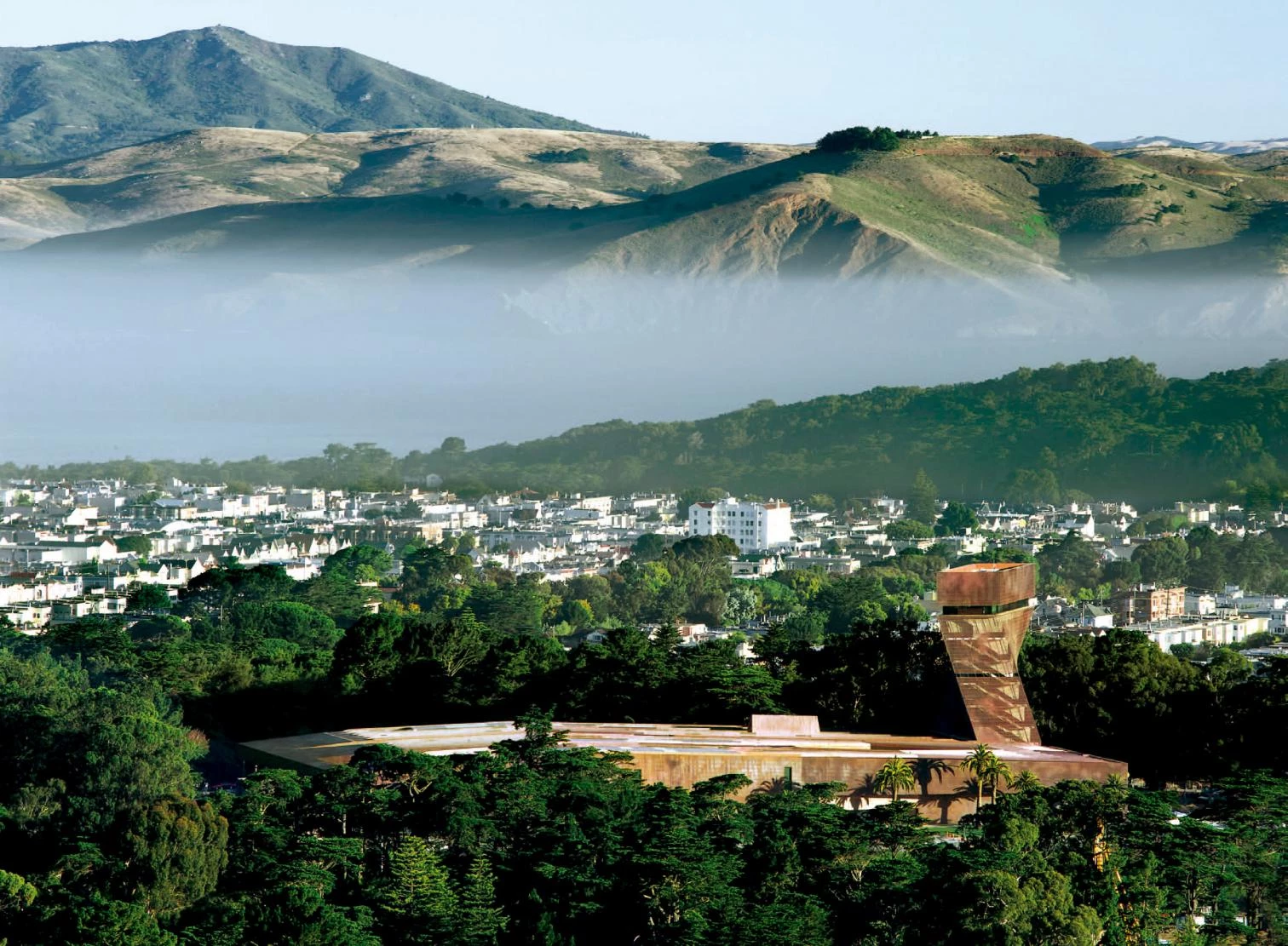

Tuesday in San Francisco I devote entirely to the New de Young Museum, a work of Herzog & de Meuron I get to visit on the eve of its opening in the company of the building’s project director, the indispensable Deborah Frieden. When I came to speak at Berkeley some years ago, I took advantage of the opportunity to verify for myself both the frustration produced by the routinary buildings of Mario Botta and Fumihiko Maki in the urban center’s cultural core, and the amazement elicited by the Dominus winery of the Swiss partners in the Napa Valley, an at once brutal and exquisite prism of basalt gabions. Now, after the controversy triggered by the project for the museum, which replaces an early 20th-century building in Golden Gate Park that was damaged by the 1989 earthquake, it is a joy to find that the building housing the centenary institution is at a par with its artistic-ethnographic collections, and that its composition of pieces interwoven to connect exhibition narratives leaving deep chinks of light and vegetation in the interior, or its skin of copper that will turn green in time and which is embossed and perforated with a pixellated interpretation of the foliage, will end up convincing the most reticent. Enriched by ex profeso works as enigmatic as Goldsworthy’s lyrical fissure or Richter’s micro-photographed strontium, and crowned with a 45-meter look-out tower that twists slightly to align with the urban grid, the New de Young is the laconic icon that San Francisco lacked all these years, a luminous meeting place where the city comes together and can be contemplated.

In Seattle, the library by OMA is both spectacular and populist whereas in Minneapolis, the failed Guthrie Theater by Nouvel contrasts with the elegant Walker Art Center by Herzog & de Meuron.

Wednesday in Vancouver revolves around the overwhelming landscapes of the Canadian Pacific, which makes the visitor shudder from the moment he flies over the islands of the gulf, shrouded in the autumn mist. In the intermittent rain I discover the tranquil urbanity of an orderly and friendly city whose population is one-third Asian and whose economy until recently centered around fishing, mining, and timber. Here it is a must to visit the most promising among studios on the rise, and John Patkau leads us to his latest house, a refined residence for a young Chinese millionaire, built in concrete on the water’s edge, that features a suspended swimming pool, a hermetic music room for the jam sessions of his rock group, and a bedside photograph that in lieu of a family shows a lineup of his seven luxury cars, for which the garage allows vertical storage. But the leading local architect is the veteran Arthur Erickson, and after visiting his capolavoro, the monumental and tectonic Anthropology Museum, it is my good fortune to lecture in an auditorium that he designed, and that clings to words and movement like a used glove.

Thursday in Seattle has as its inevitable target Rem Koolhaas’ Public Library, a huge carved crystal whose Stealth aesthetic has had a curiously polemic-free reception, however much the young accuse the Dutch architect of having attained mastery with a faceted sculpture that contradicts his most extreme postulates, and that in any case orchestrates a polyhedric program with strategic intelligence and material elegance. Largely occupied by humble users, the titles on loan that are shown in real time through an artistic installation give a further cue to the social character of the institution. More melancholic was the visit to Frank Gehry’s Experience Music Project, a formless amalgam of chaotic iridescent bulges that not even the monorail penetrating it or the fairground proximity of a roller coaster redeems, and whose capricious confusion is all the more evident when seen from the top of the Space Needle, the slender observatory that was built for the 1962 World’s Fair. The city of Jimi Hendrix is also the city of Steven Holl, but the latter’s university chapel will be a disappointment to most: balanced in its implantation and exact in its details, the trivial scenography of the interior, with its low colored lights trying to create a spiritual atmosphere, are decidedly affected and twee, in unfavorable contrast to the constructive pedagogy of the tilt-up walls. In any case it is better than Gehry’s blobs and the stilted, cutout pop of Venturi & Scott Brown’s museum, works unworthy of a place whose most memorable image continues to be the unanimous spread of Boeing hangars, which Microsoft’s virtual universe has not managed to dissolve. Despite the instantaneous and oceanic information available on-line, architects still buy tickets to attend a lecture, and this persistence of physical presence never fails to surprise me.

Friday in Minneapolis is a rainy day and my stopover in the Midwest has no other objective than a visit to the newly opened Walker Art Center, a Herzog & de Meuron project that has been received with lots of praise and a few reservations. All have lauded the way the new halls thread their routes with the old building of Edward Larrabee Barnes, the skill with which the center relates to the avenue and the placid park behind, or the inventiveness of the materials, which include a cladding of aluminum panels that are pressed to give them the look of creased paper. But not everyone has understood the random perforations of the outer skin, or the use, in the theater and the openings of the halls, of a decorative pattern that takes inspiration from the sensuality of lace lingerie. Nevertheless it is hard to be objective when touring the place in the warm company of its director, Kathy Halbreich, a New Yorker who has kept high the reputation of a museum that is exemplary for its integrity and consistency. The stop at the Twin Cities also gives me time to experience the unique system of raised skyways that connects all of downtown Minneapolis to shelter pedestrians during the city’s tough winters, to explore the precedents of the Guggenheim-Bilbao in Gehry’s efficient and stunning Weisman Museum, and to lament the clamorous sign of alarm that hovers over Jean Nouvel’s career on account of his Guthrie Theater, a colossal work on the banks of the Mississippi that is his first American job but where every decision and every detail, from the clonal hall to the gymnastic projection over the river, shows a loss of control that does no justice to the institution nor to the architect’s track record. Saturday has me flying back home via Chicago. This time I get no SSSS. I am no longer under suspicion.