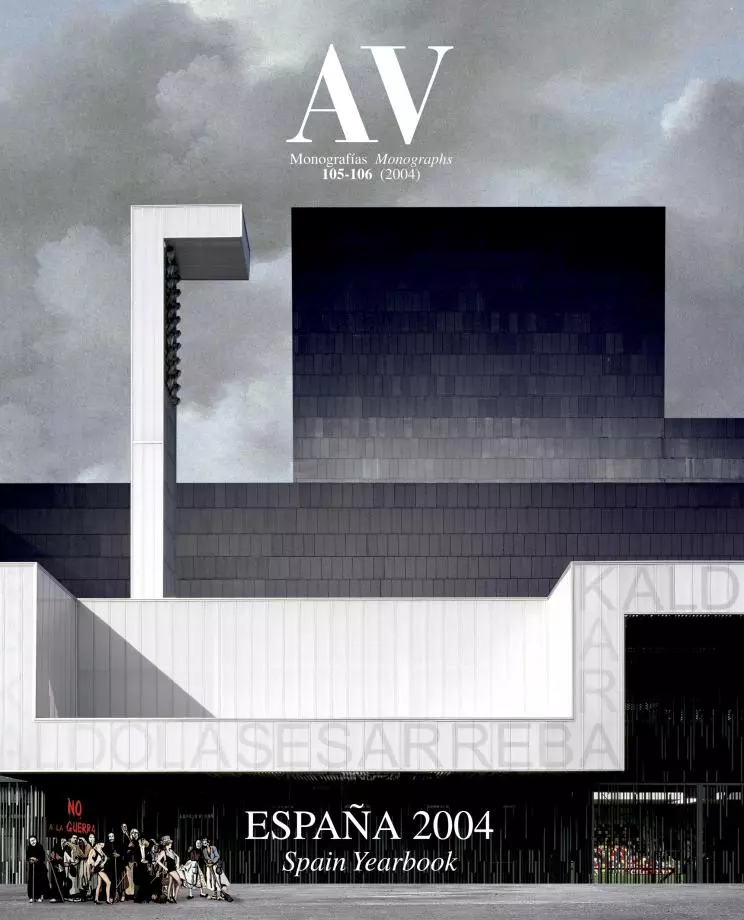

Fisac, Finally

The inventive and prolific career of Miguel Fisac, who is now 90 years old, goes through all the social and aesthetic periods of the Spanish modernity.

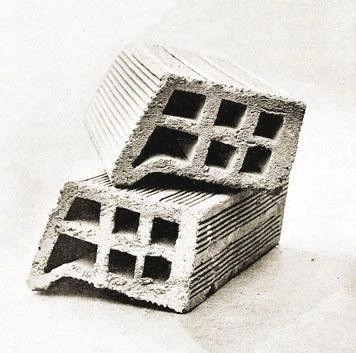

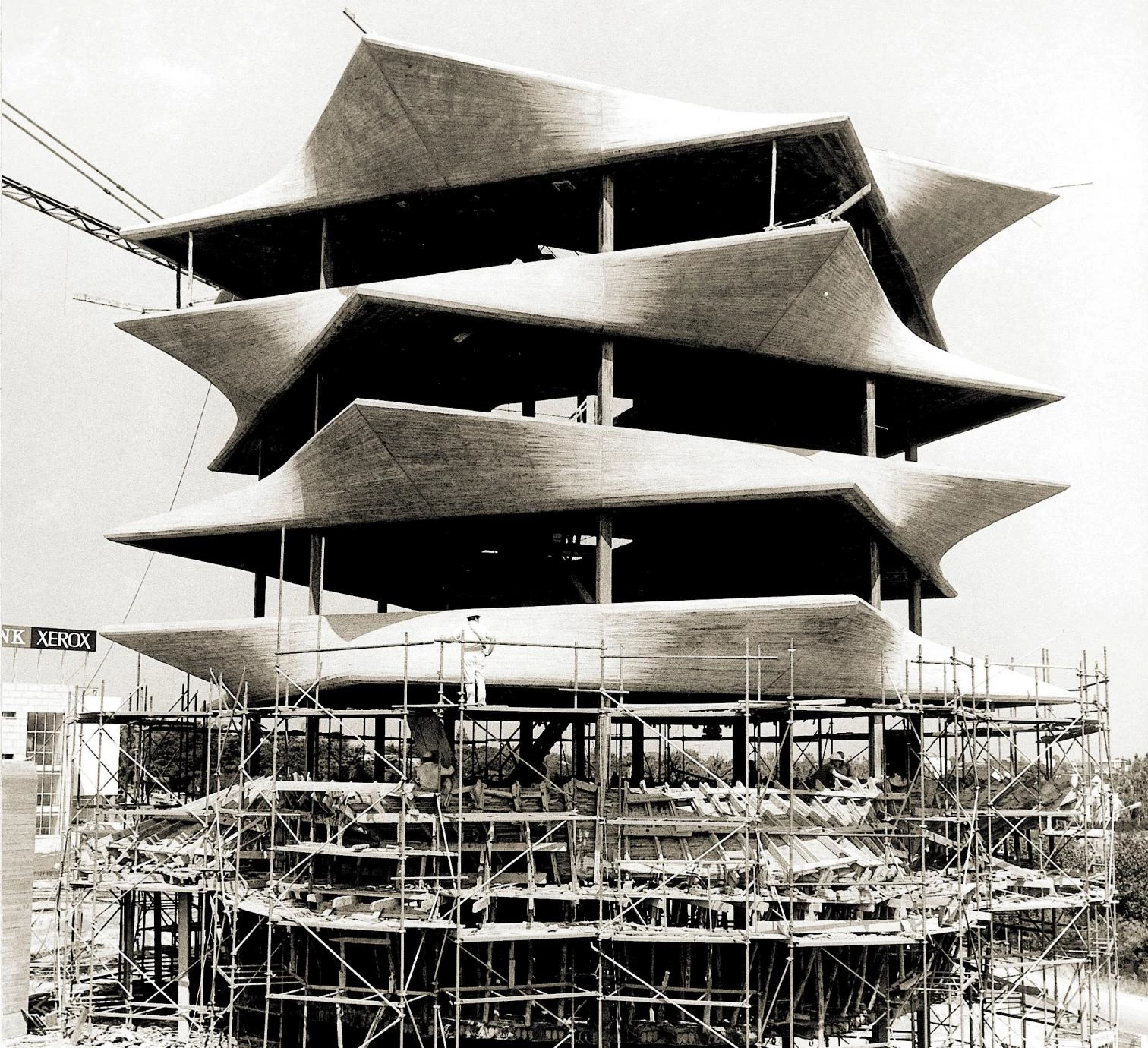

Tireless inventor, Miguel Fisac cherishes his patents as much as his buildings. From the hollow brick that he registered in 1952 to the prefab-rication system registered last year, on to the bone-beams, the flexible formworks or the supports for lamps and furniture, the nonagenarian architect leaves behind half a century of patents in a dozen countries; he has even patented his own name as commercial brand. And the fact is that planet Fisac designates a territory full of technical innovations, design experiments and aesthetic adventures that summarize the contemporary history of Spaniards through the impatient itinerary of an abrasive and singular talent. Paradoxically for one who is above all a builder, his journey starts with a demolition, and culminates with another: in 1942, Fisac raised in Madrid his first work, the church of the Espíritu Santo, over the remains of the auditorium of the Residencia de Estudiantes, materializing the national-catholicism of the victors of the Civil War in the emblematic site of Republican secular culture; and in 1999, the protested demolition of his fanciest building, the popular ‘pagoda’of the Jorba laboratories on the highway of Barajas, acknowledged the architect’s media prestige in a country fully immersed in the narcissistic and prosper

From the Beaux Arts academicism to soft concrete, and through the temperate modernity of Nordic influence, the career of the architect from La Mancha is rich in technical experiments and aesthetic adventures.

The sloping brick, the concrete bones and the flexible formworks mark creative phases.

Son of a well-to-do pharmacist, Miguel Fisac was born in Daimiel in 1913, and after initiating in Madrid studies interrupted by war – in which he fought on the national side –, started upon gradu-ation a privileged relationship with the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (directed at that time by José María Albareda, his fellow at the Opus Dei) which would leave him in charge of the remodeling during the forties of the mythical ‘Colina de los Chopos’, where the new Franco regime hoped to materialize its own ideological project. The church of severe brick and bold geometries is the first work he completed, and its construction over the mutilated walls of the demolished auditorium of Arniches and Domínguez – a process that the architect Francisco Burgos has studied in great detail – has a symbolic dimension that can hardly be overstated. In the remaining buildings, Fisac went from the Corinthian classicism of the portico of the Casa Central to the metaphysical laconicism of the propylaea that give access to the precinct, to move on towards a Nordic-flavored empiricism in the interiors of the Optics Institute or in the library of the cloister of the Espíritu Santo.

At the end of the decade, with the commission of the Cajal Institute, Fisac abandoned the beauxartian academicism to embrace a tempered and organic version of the modern that was stressed after a trip to Scandinavia, and he would draw inspiration from that inventive functionalism for his other projects of the fifties, from the Labor Institute of Daimiel or the Teacher Training Center in the Madrid university campus to the Dominican Fathers’ Schools in Valladolid or Alcobendas, with scenographic churches that will transform their au-thor into an acknowledged specialist in religious architecture, and a champion of the technical or aesthetic aggiornamento of Spanish society. The stylistic changes would be followed by a spiritual catharsis, and after a trip around the world in the summer of 1955, Fisac left the Opus Dei the day after his 42nd birthday, with the inevitable public echo brought about by his fame. His marriage two years later to Ana María Badell – with Dr. Marañón acting as godfather at the wedding – opened a new stage in the architect’s biography, within the context of a country experiencing the growth of the economy and the awakening of political dissidence.

Concrete Bones

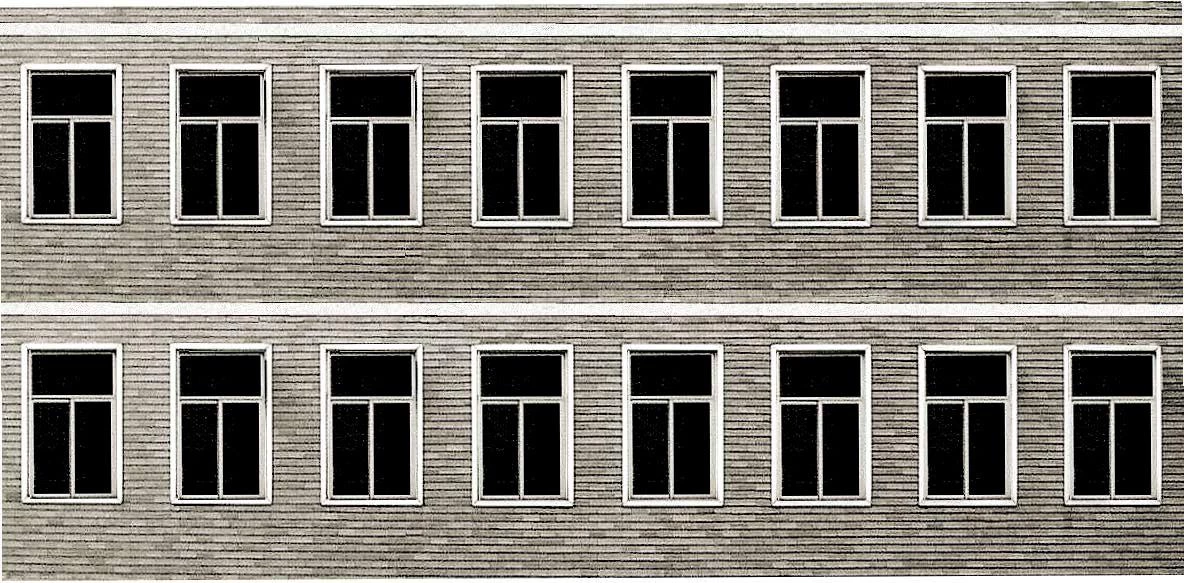

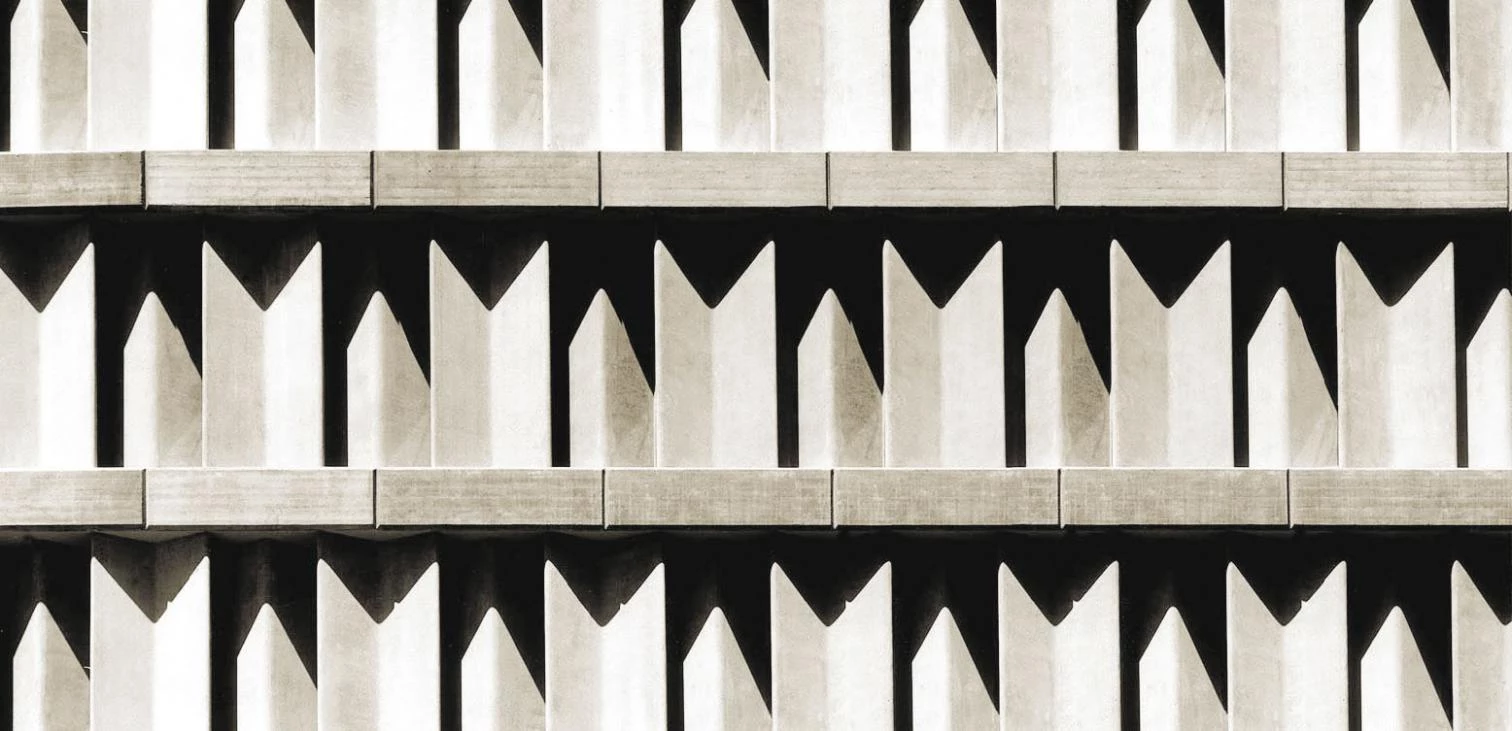

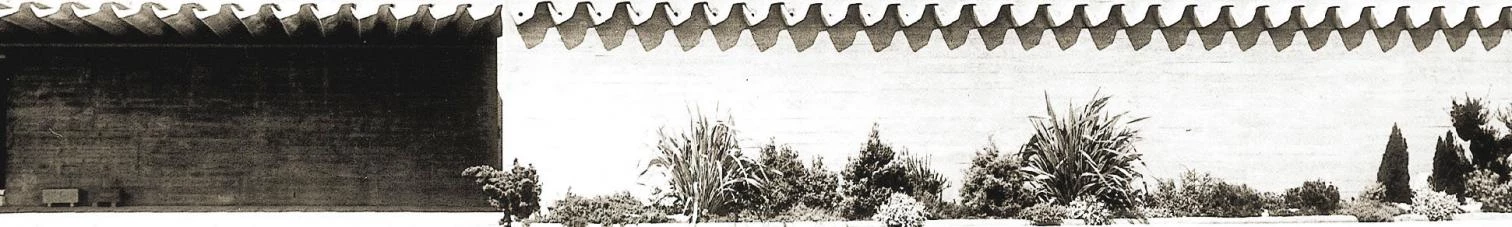

In the sixties Fisac lived his most fertile moment, with the invention of the concrete ‘bones’, the light and sculptural beams with a hollow section and organic appearance with which he carried out most of the works of the decade, large industrial warehouses for laboratories, wineries or factories that reflect a prosperity triggered by the discarding of autarchy and the liberalization of the economy. Used for the first time in the pharmaceutical laboratories Made, the ‘bones’reach their most eloquent and exact expression in the Center for Hydrographic Studies, an impressive concrete box by the Manzanares River that houses a murmuring set of models of ports and reservoirs beneath the bright and vertebrate canopy of beams built with post-stressed voussoirs – so characteristic in their junctions that when they were replaced in 1994 by pre-stressed beams of one piece, these were shuttered with a mold that feigns the grooves of the original ones, as the architect Francisco Arqués has duly recorded –. Similar ‘bones’ were also used in the Garvey Winery of Jerez de la Frontera or in sever-al factories of Barcelona, were placed vertically as brise-soleil in Madrid’s IBM building, and were combined with flexible formworks in the architect’s own studio in Alcobendas.

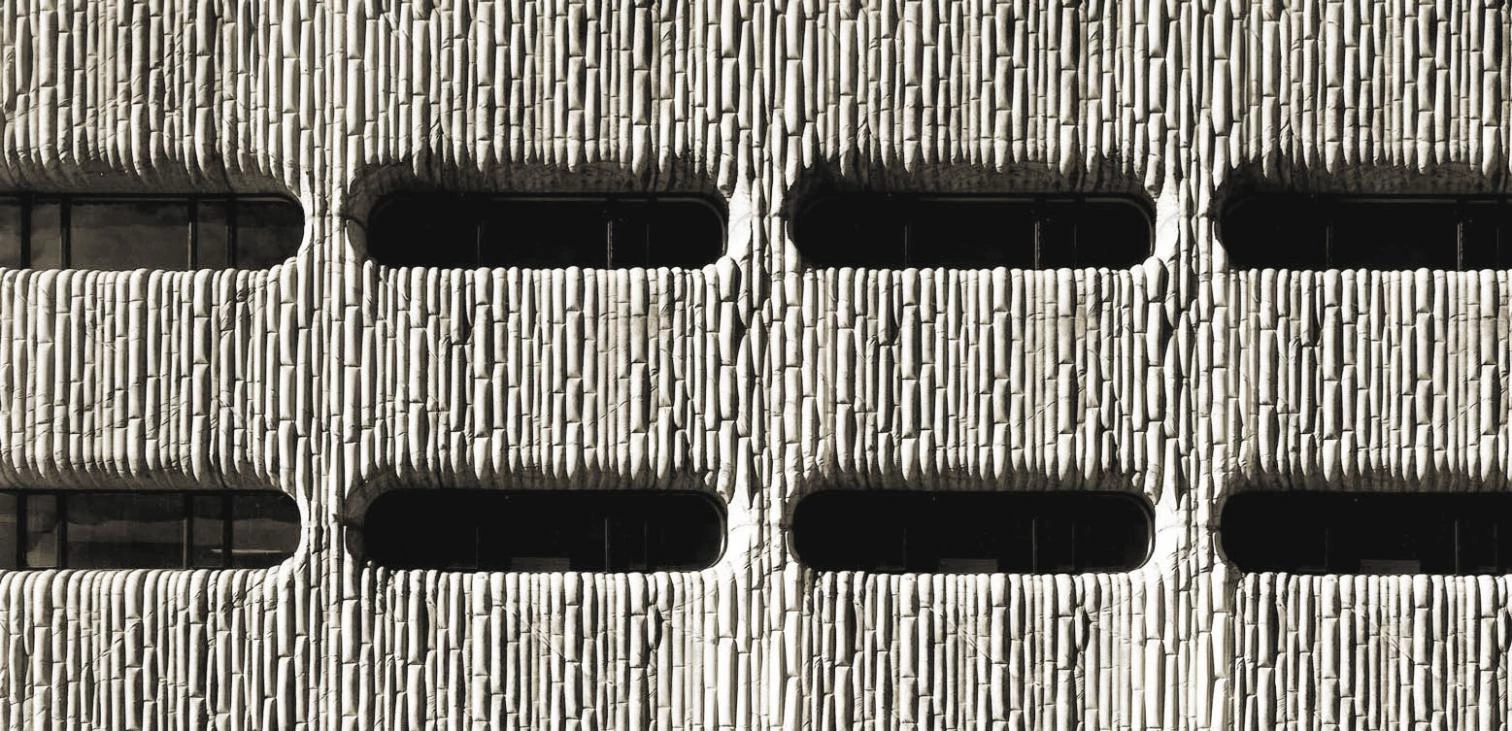

Both Made and the Center for Hydrographic Studies (opposite page, top and bottom) served to test the bone-beams; with floors joined by hyperbolic paraboloids, the Jorba tower (below) became an icon of sixties prosperity.

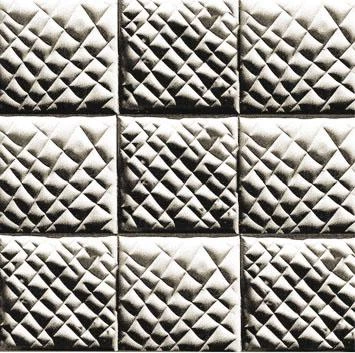

These formworks made with plastic sheet and ropes, which give the concrete the soft appearance of a stone mattress or thick packaging, were used at the beginning of the seventies at the Mupag Rehabilitation Center in Madrid, and they have ornamented Fisac’s work – gradually less frequent, and very sporadic since 1997, when his studio closed down – during the last three decades, appearing in small public buildings and in houses such as the cushioned box of La Moraleja or the one that he remodelled for himself in Almagro with peculiar surrealism, extending also to his two most recent projects, the theater of Castilblanco de los Arroyos and the Getafe sports center, both finished in time for the architect’s 90th anniversary. In these projects Fisac stubbornly perseveres with these flaccid or rough surfaces which have seemingly had such bad critical fortune, but that ought to be rescued today from the decorative and tactile experiences that have radically changed the skin of contemporary architecture. Estranged from public attention, the Fisac of the transition and democracy has kept on exploring the aesthetic of concrete in his secret pharmacy, happy and irate as the lucid old man that he is, and with the obstinate tenacity of one who re-mains faithful to modernity as invention.

Perhaps for this reason it is ironic that his most publicized work, described by the architect as “a completely insignificant frivolity” – the star-shaped tower of the Jorba laboratories, that with its floors rotated 45 degrees and its concrete hyperbolic paraboloids tried to comply with the client’s desire to attract attention, and whose pagoda profile became an icon of the impetuous, naive prosperity of the sixties – would be the one to turn the spotlight back on Fisac, indelibly linking his figure, in the public imagination, with an acrobatic tower. But the heart has reasons that reason cannot know, and the covetous demolition in 1999 closed the loop opened by the ideological demolition of 1942 to complete with poetic justice a virtuous circle of amnesia or amnesty in a country suffering from a feverish fit of violent memory and graves removed.