The Plenitude of the Void

The architecture of Kengo Kuma is an exemplary exercise in relinquishment. Though in his work material is particularly important, each and every one of the projects expresses a will to attain bareness that we can only call spiritual. The dissolution of form through light and the elementary fragmentation of the different materials creates atmospheres of exact serenity and simplicity, which Juhani Pallasmaa calls ‘lyrical’ because it is difficult to see them in a different way, but that could also deserve to be considered ‘spiritual’ because they take aesthetic experience to a higher level of contemplation where – as in the best Noh theater – emotion springs from stillness. The great playwright Zeami proposed moving the heart of the spectators of that Japanese theater genre by eliminating dance, music and even words, and maybe Kuma achieves a similar effect waiving all formal resources to dilute space in a bright void.

This detachment from the necessary, linked in the West to the Zen doctrine, to silence and to meditation as motionless sources of vital and spiritual elegance, has found many interpreters, but perhaps none as lucid as Octavio Paz, who found in Japan a school of sensitivity, because in contrast to India “it has taught us not how to think, but how to feel.” In his essay on the tradition of haiku, the Mexican writer illustrates the ‘plenitude of the void’ with Matsuo Basho: ‘Narcissus and folding screen: / one illuminates the other / white on white.’ “In three lines the poet defines the figure of illumination and, as if it were a cotton flock, blows on it so it disappears.” The effect of Kuma’s lightweight spaces is not so different – not to mention installations as ethereal and emotive as those of the Royal Academy in London –, a perfect expression of Octavio Paz’s bold statement: “refinement is simplicity; simplicity, communion with nature.”

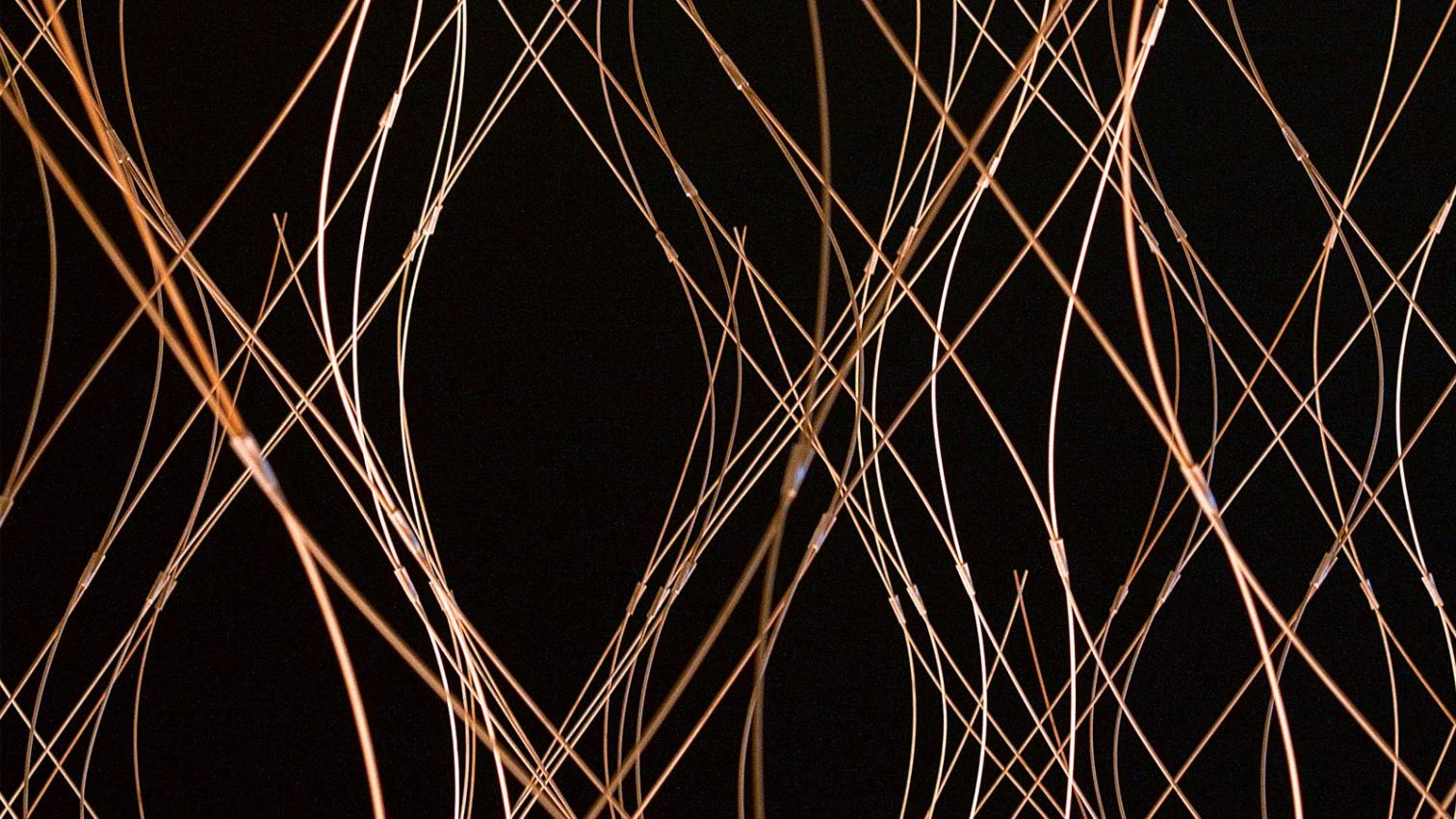

In Kuma’s body of work, communion with nature is expressed in the lyrical abstraction of bareness, but also in the tactile palette of materials extracted from the earth where they sit, and with which he creates intangible atmospheres and subtle worlds surely not so different from those cherished by the poet Antonio Machado, “weightless and gentle as soap bubbles.” His contemporary the philosopher Miguel de Unamuno thought that the poet’s task is precisely to ‘carve the fog,’ digging out ideas coined with exact words from the imprecise magma of feelings and thoughts, just like the sculptor extracts figures from a formless stone, and perhaps for this very reason the materials used in his works are arranged in this issue in a gradually fading sequence, starting out with stone and ceramic, and dissolving into shreds of mist with the vegetal fibers. ‘It is spring: / the hill with no name / in the fog.’

Luis Fernández-Galiano