Forensic Architecture is a research group based in Goldsmiths, University of London. It is also the name that the group has given to a new field of exploration. Using techniques belonging to architecture, Forensic Architecture analyzes images, sounds, and buildings in combing contexts of conflict for evidence of human rights violations. From April to October the MACBA hosts the group’s first exhibition in a major museum. Significantly, it begins with examples that bring us back to the lawsuits against Nazi war crimes.

Banality of Evil

On 11 April 1961, the trial of Adolf Eichmann began. This was the official who was much responsible for the deportations to concentration camps. A total of 112 took the witness stand, mostly survivors of the Holocaust. Fourteen years later, when the remains of the physician Josef Mengele were exhumed from a tomb in a São Paulo suburb, the identification of the corpse brought together a plethora of experts for analysis of the bones and skull. For Forensic Architecture, these two events marked a judicial paradigm shift, with the so-called ‘age of the witness’ giving way to a forensic judicial culture whose procedures were immersed “in matter and materialities.”

The selection of these two histories is no coincidence: the architect Eyal Weizman, director and founder of Forensic Architecture, was born in Israel and received training in the defense of human rights in this area. His origins are important to our understanding of the practice of his group: the trials of Nazis were a major action against the crimes of a state, bringing to the dock the leading members of a government and therefore affirming their non-impunity. Following this principle, Forensic Architecture seems to want to extrapolate to the present the practice of demanding the accountability of states, and punish violence wrought by powers-that-be.

Materials and Cases

An undeniable position of inferiority accompanies the act of looking for evidence incriminating governments or other powerful entities. So, Forensic Architecture works with what it can find: recordings with security cameras, signals detected by ocean radars, or audiovisual materials noted by witnesses and posted on Internet. Using the web as a test file, the group carries out what has been called ‘open-source research,’ a practice in expansion that helps itself to the vast multiplication of elements available in the world of the web. In the career of Forensic Architecture, the cases are varied and the contexts very different. Each one of them seeks to expand the practice of the group and conceive new methods.

The Pakistani region of Waziristan is one of the places most prone to drone attacks. This zone is not only closed to the entrance or exit of people; images are not spared the siege either. When a video of a drone attack was filtered out in 2012, it got to the press after passing through six hands. Starting with a detailed study of photograms, Forensic Architecture was able to determine the exact location of the bombed dwelling, and by means of the bullet shell, identify the weapon used. The study of lights and shadows, in combination with the localization on the map, made it possible to know the time of an attack denied by the authorities and normally invisible to the media.

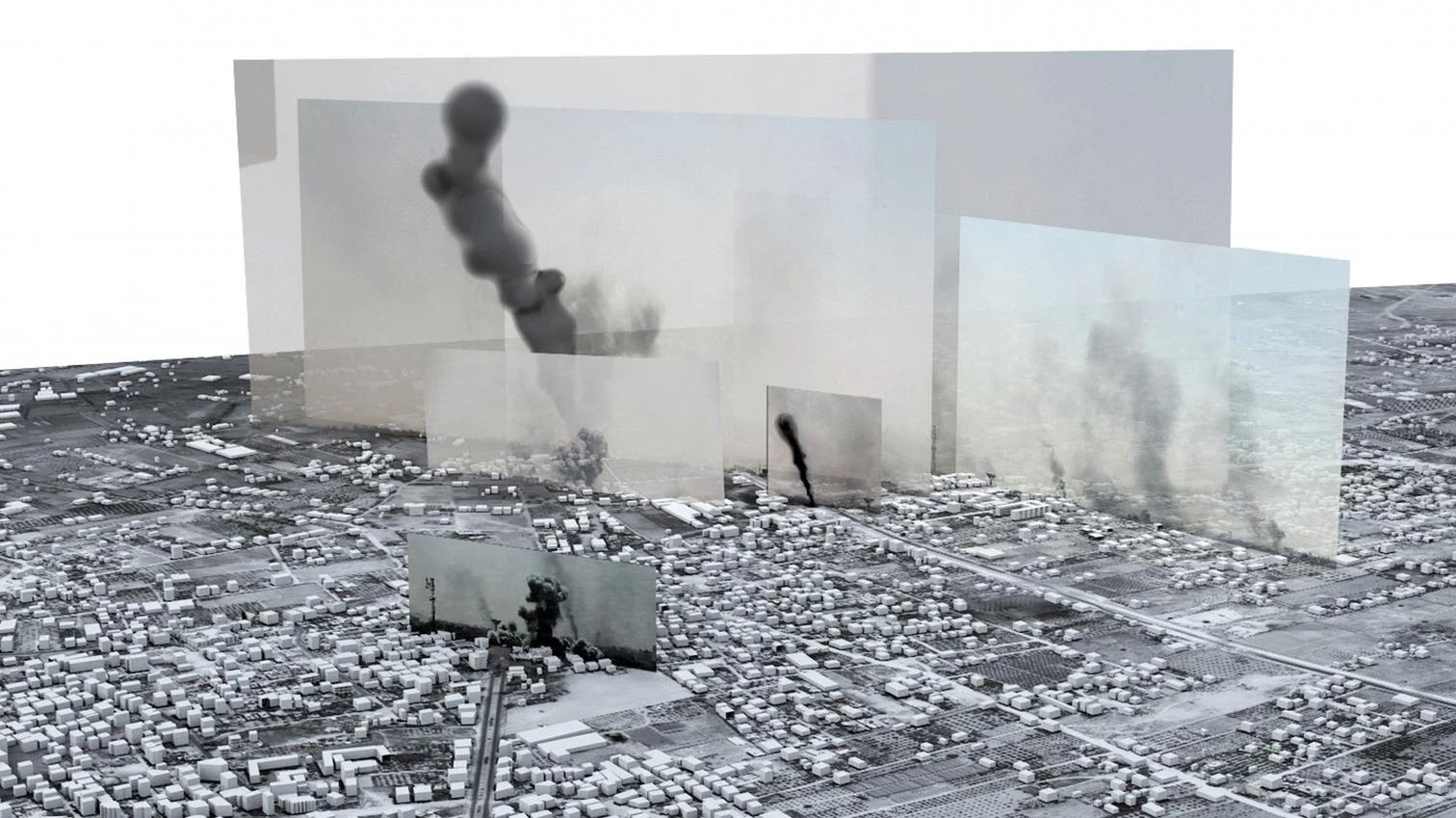

Using numerous visual elements found, the team has conceived original devices, such as what is called ‘Image Complex.’ This procedure first cropped up during the investigations on Israel’s ‘Black Friday’ attacks on the Gaza Strip in August 2014. The investigators could not actually go to the site, but analysis of explosion clouds appearing in hundreds of videos and photographs – many of them taken from social networks on Internet – revealed the precise moment and place of the various attacks, establishing a detailed chronology of the bombings.

But pictures are not always available. There are no photographs, for example, of the prison of Saydnaya, Syria. Al that the investigating group could rely on were testimonies of former prisoners, who recounted their experiences of torture and confinement, during which they were forced to remain in silence and darkness. Using architectural models and spatial studies of echoes, Forensic Architecture managed to transform traumatic reminiscences into an architectural model, a reconstruction of the prison.

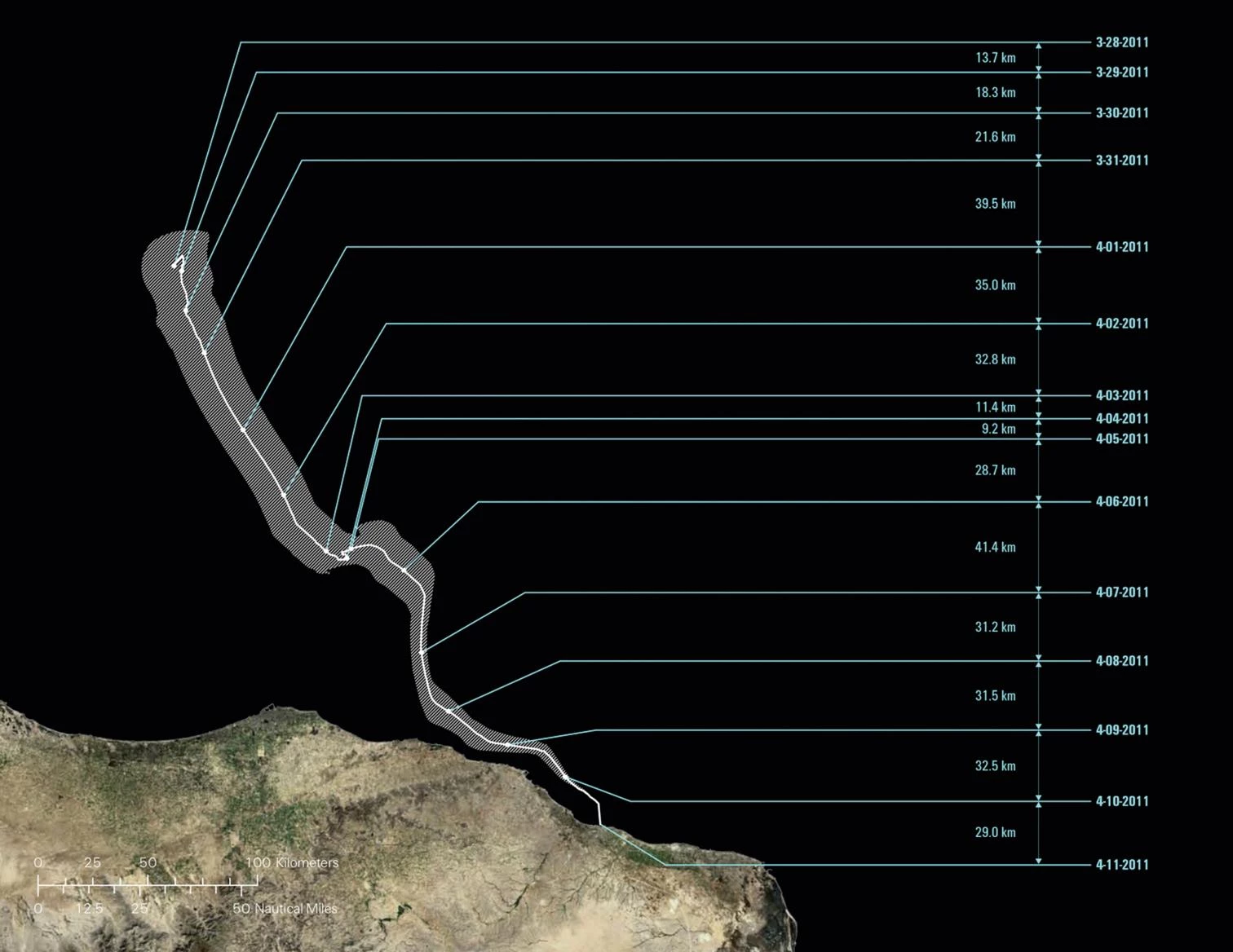

The sources used can be more immaterial: through radars commonly used to control migration, they were able to demonstrate that nothing was done to help those on a refugee boat that went adrift in an area closely watched by NATO.

Signs of the World

As part of theur work, Forensic Architecture disseminates its experiences through a multitude of videos and images of an informative nature: more than the investigation itself, the production of a narrative that shows its processes is fundamental to the team. Reflecting on the origins of the term, they stress the rhetorical sense of their practice, insisting that we take the forensic as “the art of the forum.” And this forum they refer to would not only be in the courts, but also in the public perception of crimes under investigation.

The team speaks of how truth does not exist on its own, but has to be expressed to become tangible and affect the world. Visualization of investigative practices also takes its spectators to be a people’s jury that has to be convinced through painstaking presentation of the steps of the inquiry. Unfolding its work before the media, academic circles, artistic spaces, and judicial environments, the group moves about in different contexts, each one with its particular potential.

In exhibitions like MACBA’s current one, Forensic Architecture presents its work through videos and installations which adopt the language of contemporary art. This is placed in consonance with the art school at Goldsmiths, and with the disciplinary background of the team members, mostly artists and architects.

Nevertheless, in the group, architectural sensitivity works on a deeper level, linking up with the actual way that space and its interactions are understood. Through interdisciplinary work, artists’ and architects’ tools and particular way of looking at things are placed at the service of a field differing from the usual. Hence, Forensic Architecture has created an entire methodology for reading the world’s visible signs: through close observation, image construction, and a grasp of urban phenomena, it is possible to understand and prosecute destruction and violence. Beyond the desire to build, Forensic Architecture turns its attention to ruins. And in this way, from the rubble, it seeks to contribute to building the transnational culture of human rights more solidly.

Julia Ramírez Blanco teaches art history at the University of Barcelona and is the author of Utopías artísticas de revuelta (Cátedra, 2014).