Terragni in Vanishing Point

The centenary of Terragni sheds light on the greatest modern Italian architect, whose ties to fascism have been a permanent source of discomfort for the critics.

White architecture for blackshirts: such has been the formulaic judgment of the work of Giuseppe Terragni, who after short of fifteen years of professional life left behind a tight bundle of masterful buildings that were at once modern and fascist. In his endeavor to express a new artistic and political order, the author of the Casa del Fascio in Como – perhaps the most important work of Italian rationalism – intervened in aesthetic debates and in public life with equal passion, and his inextricable marriage of architectural excellence and totalitarian militancy was an inevitable cause of embarrassment for the historiography of the victors of the Second World War. Born on 18 April 1904 and active as an architect from 1926 to 1940, Terragni, physically and mentally devastated after 15 months on the Russian front, died of a brain hemorrhage in Como on 19 July 1943, six days before the fall of fascism: a tragically premature disappearance that, while attaching his biography to the Mussolini regime, facilitated his critical redemption in the postwar period. Thus, Terragni was saved from his political commitment by the insanity of his last days and his dramatically abrupt end.

The marble prism of the Casa del Fascio in the urban context of Como, facing the cathedral.

As early as 1950, Bruno Zevi – so fond of tangling up works with their authors that he had no problem naming Frank Lloyd Wright an ‘honorary Jew’ for the relevance of his organic architecture –, decided that the work of Terragni could only be anti-fascist and conspiratorial. Zevi said that Terragni’s radical rationalism was incompatible with the hateful ideology of fascism. To be sure, he overlooked how much exaltation of technical order there was in a fascism fascinated by futurism à la Marinetti. The wide outcry of public opinion that in 1956 prevented the demolition of the Casa del Fascio proves that, by then, the architect from Como had already been admitted into the sphere of myth. This exegetic catharsis fertilized in the English-speaking world with the young Peter Eisenman’s discovery of Terragni. Guided by his mentor, the formalist critic Colin Rowe, Eisenman traveled to Italy in 1961. It was an initiation trip, the fruits of which would nourish the American avant-garde of the seventies, and in the course of which Eisenman conceived a book on Terragni’s work that, with the definitive title Transformations, Decompositions, Critiques, has finally seen the light, forty years later.

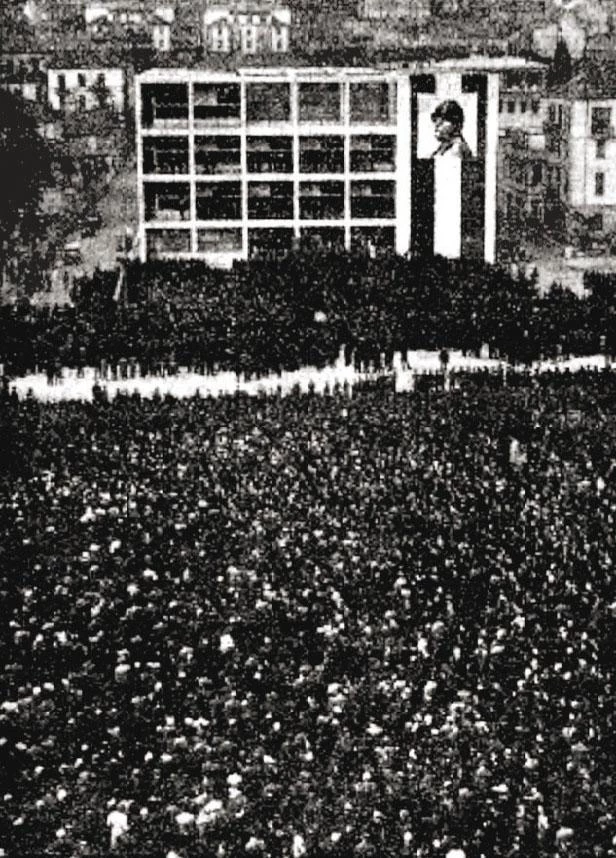

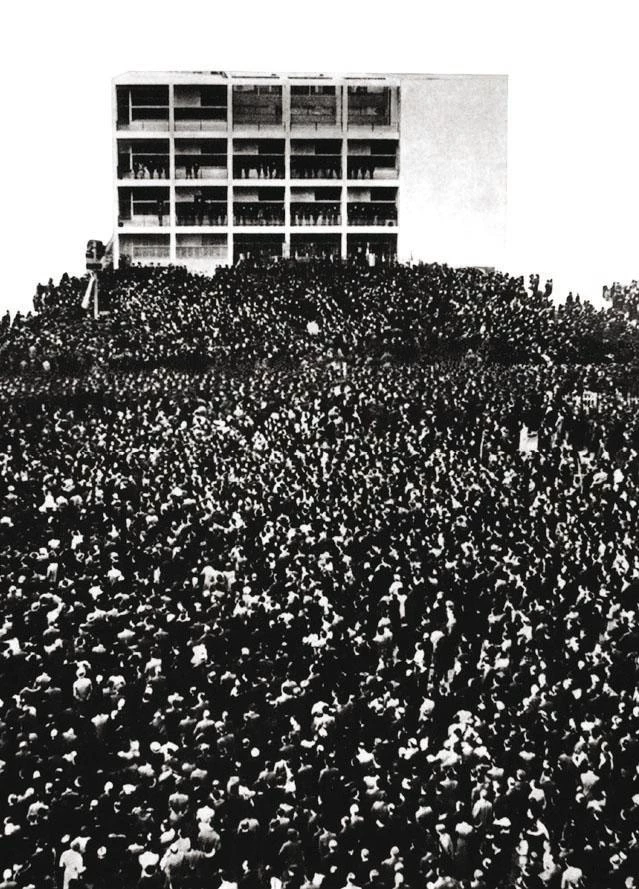

The Casa del Fascio in the local press, showing the popular gathering of 7 May 1936; in the review Quadrante, retouched to eliminate the flag with Mussolini’s portrait; and in Eisenman’s book, with crowd but without context.

In it, the purely syntactic reading of the Italian architect – as inventor of a formal grammar, along the linguistic lines of the Chomsky that colored Eisenman’s first approaches – comes to a hyperbolic paroxysm that makes the volume a monumental and astonishingly painstaking inquiry into the compositional mechanisms of Terragni, whose work is carefully stripped of all semantic content, eliminating not only its significant ties to a historic moment and its representational function within the fascist regime, but now even the urban context of the buildings discussed, which is altogether suppressed in the photographs illustrating them. But in the act of erasing time and place in favor of sequence and space, Eisenman is coherent with a view of architecture that tries to define its essence by abstracting it from circumstance. When the image of the Casa del Fascio that the book begins with is cut out of its urban environment, the operation brings to an extreme a process of de-contextualization that was already present when the work was first published in the magazine Quadrante, where the photograph of the 7 May 1936 demonstration, organized on the occasion of the fall of Addis Abeba and the proclamation of the New Roman Empire, is doctored to complete the crowd and delete from the facade the Italian flag with the portrait of Mussolini.

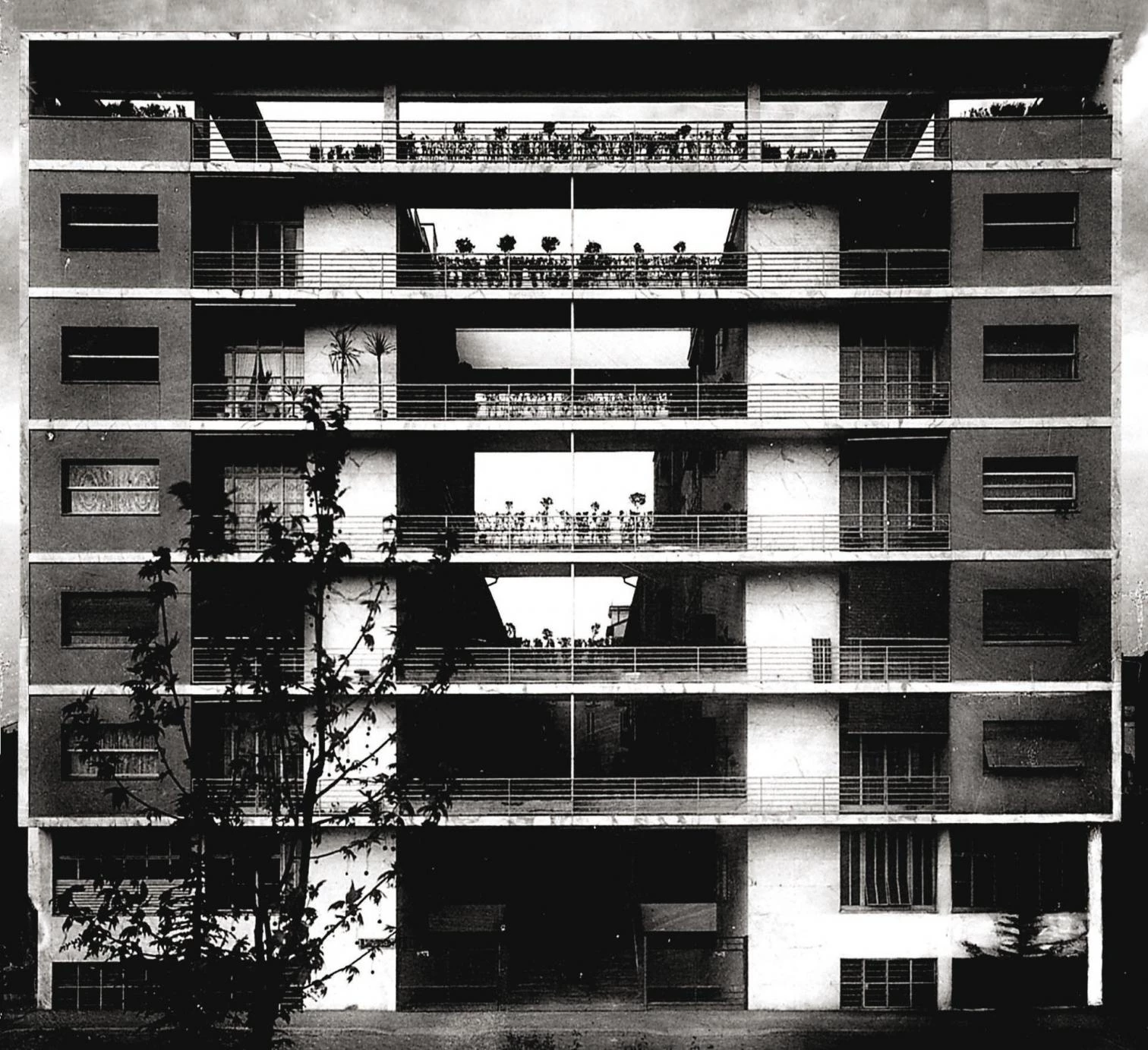

The Casa Rustici in Milan combines urbane functionalism with reluctant monumentality; the Sant’Elia kindergarten in Como joins technical ingenuity with the sliding rectangles of neoplasticist composition.

This obsessive removal of the accidental by Terragni, a process of abstraction that borders on de-materialization – which is paradoxically compatible with both the liturgical rhetoric of exterior and interior propaganda and a fussily scrupulous attention to material execution – admirably manifests the architect’s pursuance of “the absolute purity of the idea, the eternal harmony of pure art”.

Simultaneously, both geometric clarity and a non-literal definition of transparency help Terragni give form to Mussolini’s dictum “fascism is a glass house” where there must be “no barrier, no obstacle between the political hierarchy and the people”. The abstract diagram of concrete and marble, with four different facades and 18 glass doors that open simultaneously to permit direct connection between the ceremonial square and the courtyard with the cenotaph of the martyrs, is a precise monument to classicist modernity, that which Le Corbusier explored in his Leçon de Rome; and it is also a church of fascist mysticism, a premise of sublime, spectral worship that gives architectural form to the motto engraved inside: ‘Order, Authority, Justice’.

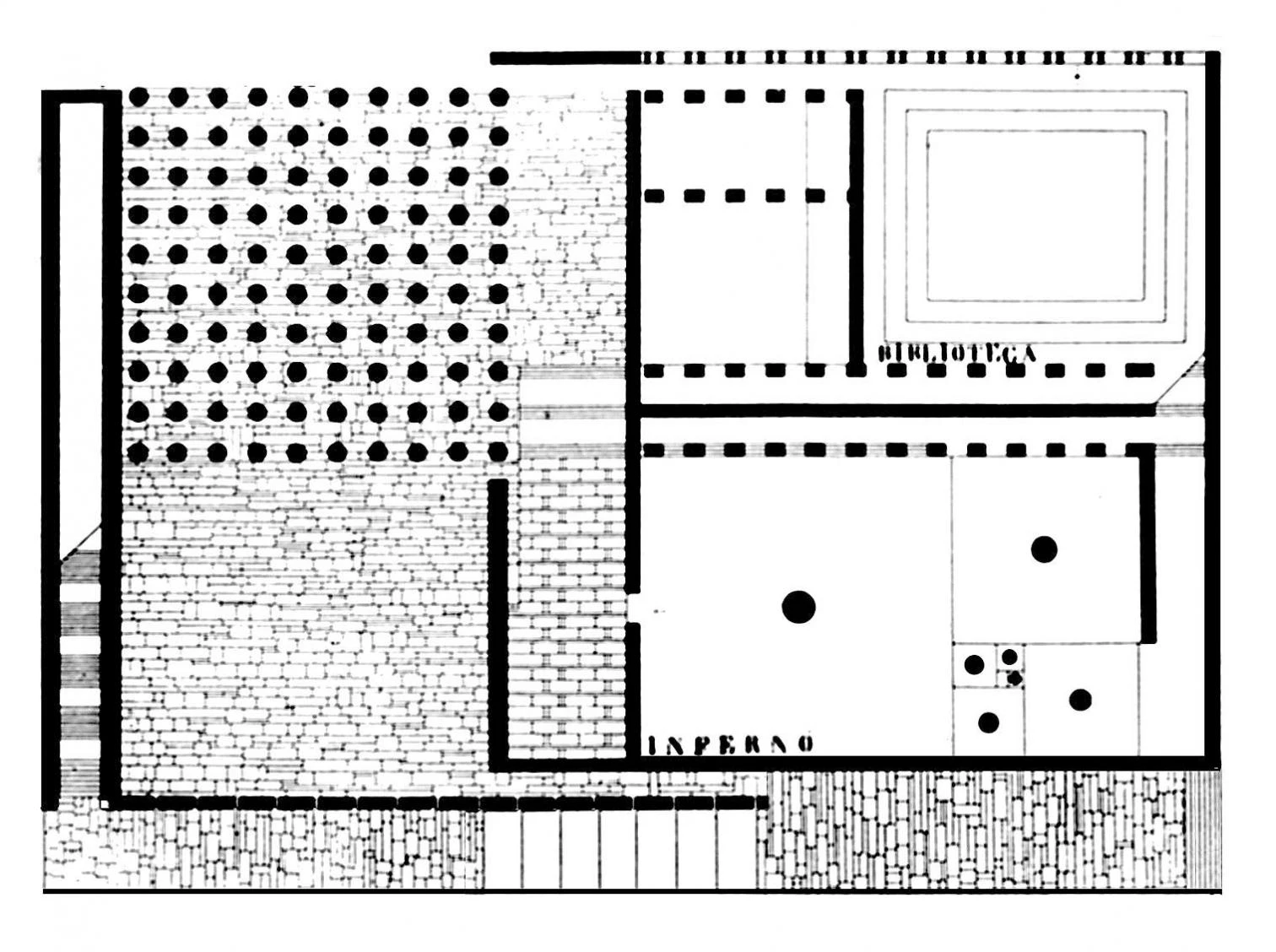

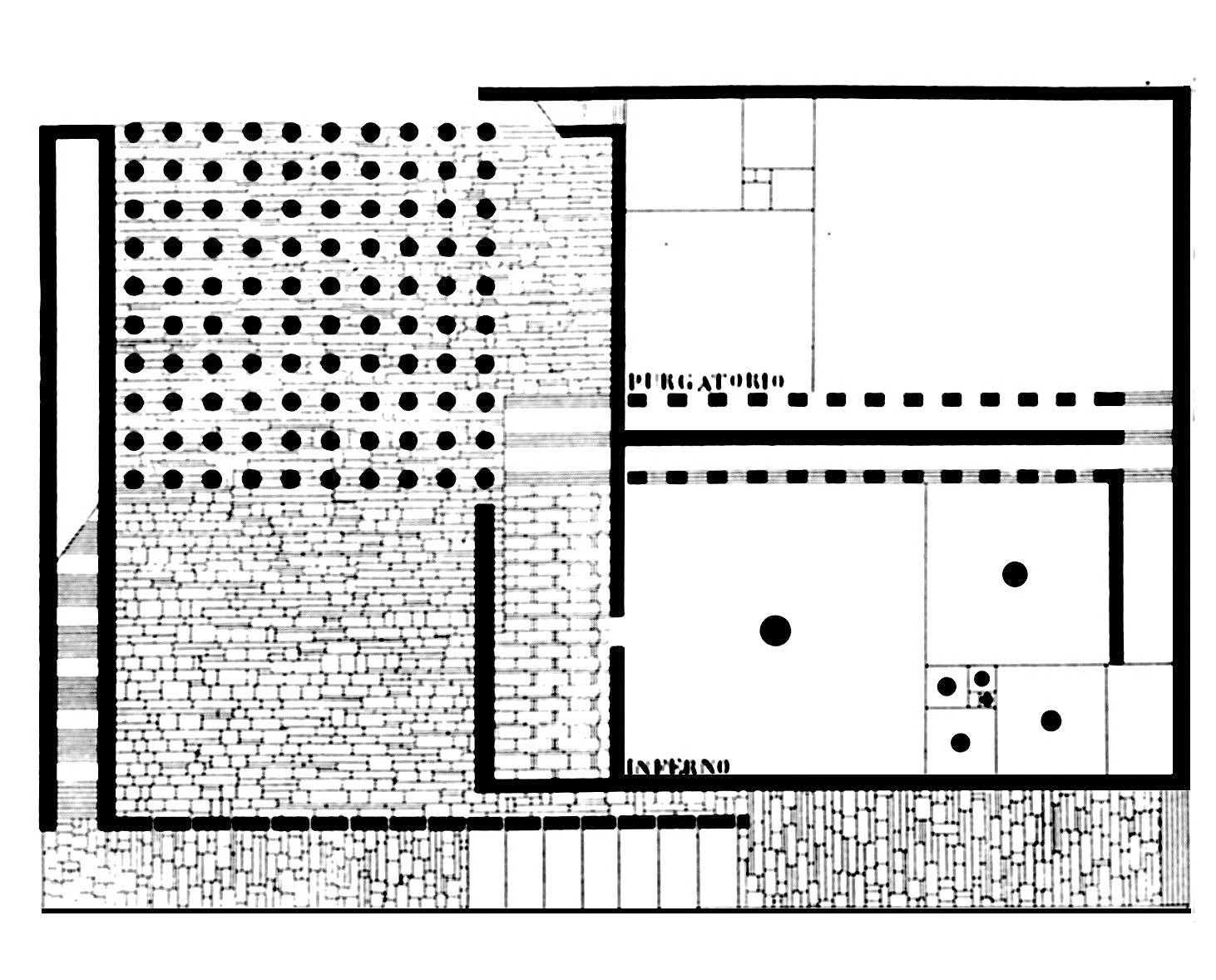

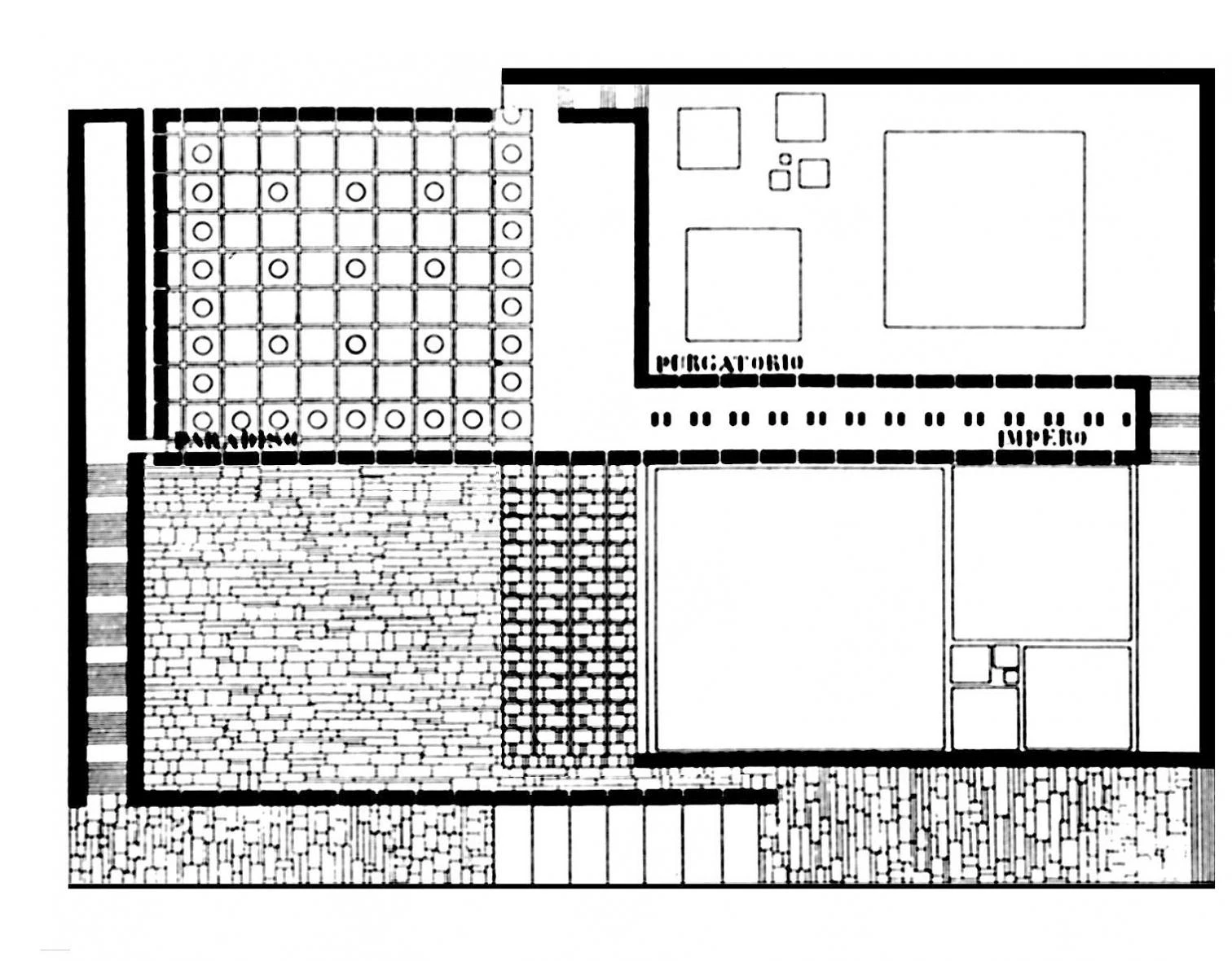

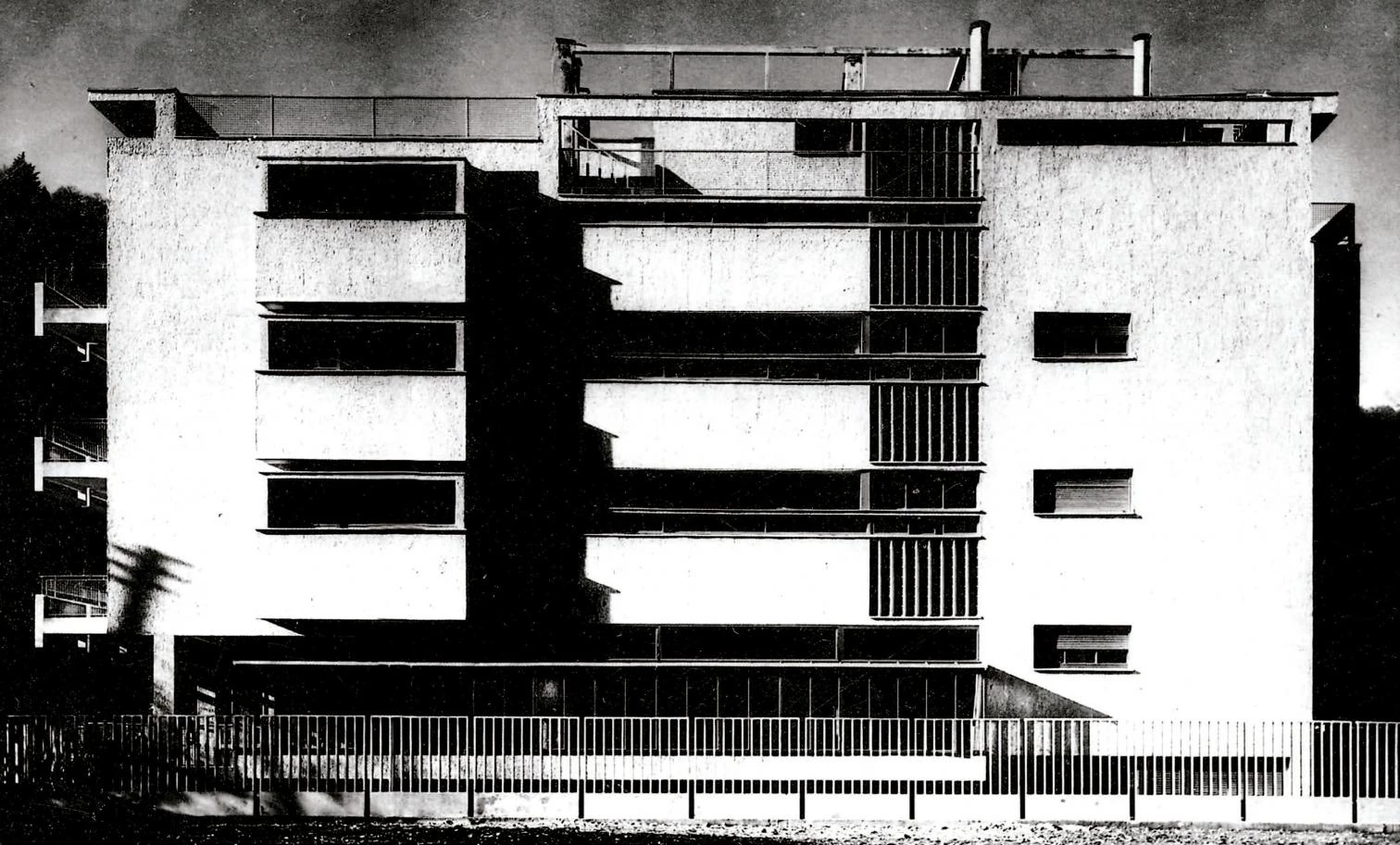

The unbuilt project for the Danteum is a symbolic labyrinth of glass columns; the Casa Giuliani Frigerio in Como, his last significant work, takes his research into the syntax of geometry to the limit.

Defending technical rationality and industrial serialization in opposition with the dynamic curves of Sant’Elia, and also far from the qualunquismo of the likewise fascist Pagano and his Casabella, from 1926 to 1931 the young members of Group 7 lived their so-called squadrista period, which they materialized in the Novocomum of Como, a large apartment block designed by Terragni with German and Russian echoes: a phase of guerrilla aesthetics on the margins of the system that ended with the commissioning of the Casa del Fascio to the podestà brother and party member Giuseppe Terragni, a 28-year-old architect who with this assignment sealed the confidence of the political establishment and entered the circles of power. Later would come the urban functionalism and reticent monumentality of the Milanese dwellings of the Casa Rustici; the neoplastic sliding rectangles and the technical inventiveness of Sant’Elia kindergarten in Como; the contrast between transparent horizontality and archaic verticality in the Casa del Fascio of Lissone; the symbolic labyrinth and glass columns of the Danteum, designed for Rome, but never executed; and the refined complexity of syntactic geometry in the Casa Giuliani Frigerio in Como, a residential building that would be Terragni’s last major work, before the draft into the army and the war trauma that would make him lose his mind and his life.

From the vanishing point of death at the wrong moment, the figure of the architect grows in the distance, freed of the burden of history, and his works acquire the timeless patina of metaphysical painting. Nevertheless, it is not in De Chirico, but in the indifferent desolation of the canvases of Terragni’s occasional collaborator, the great painter Mario Sironi, that his constructions find an echo of painful empathy, unable to separate the work from the ideas that propelled it and the time that gave birth to it. Terragni was a fascist, true, just as so many other modern architects who associated the new rational order with totalitarian dawns were communists. Great architecture, after all, was never incompatible with despotism, and the ethical and political values of democracy belong to a sphere that is quite different and quite distant from artistic excellence.