Wall and Tapestry

Herzog y de Meuron construirán en el centro histórico de Jerez una Ciudad del Flamenco con un jardín tapiado y una torre aliviada por celosías.

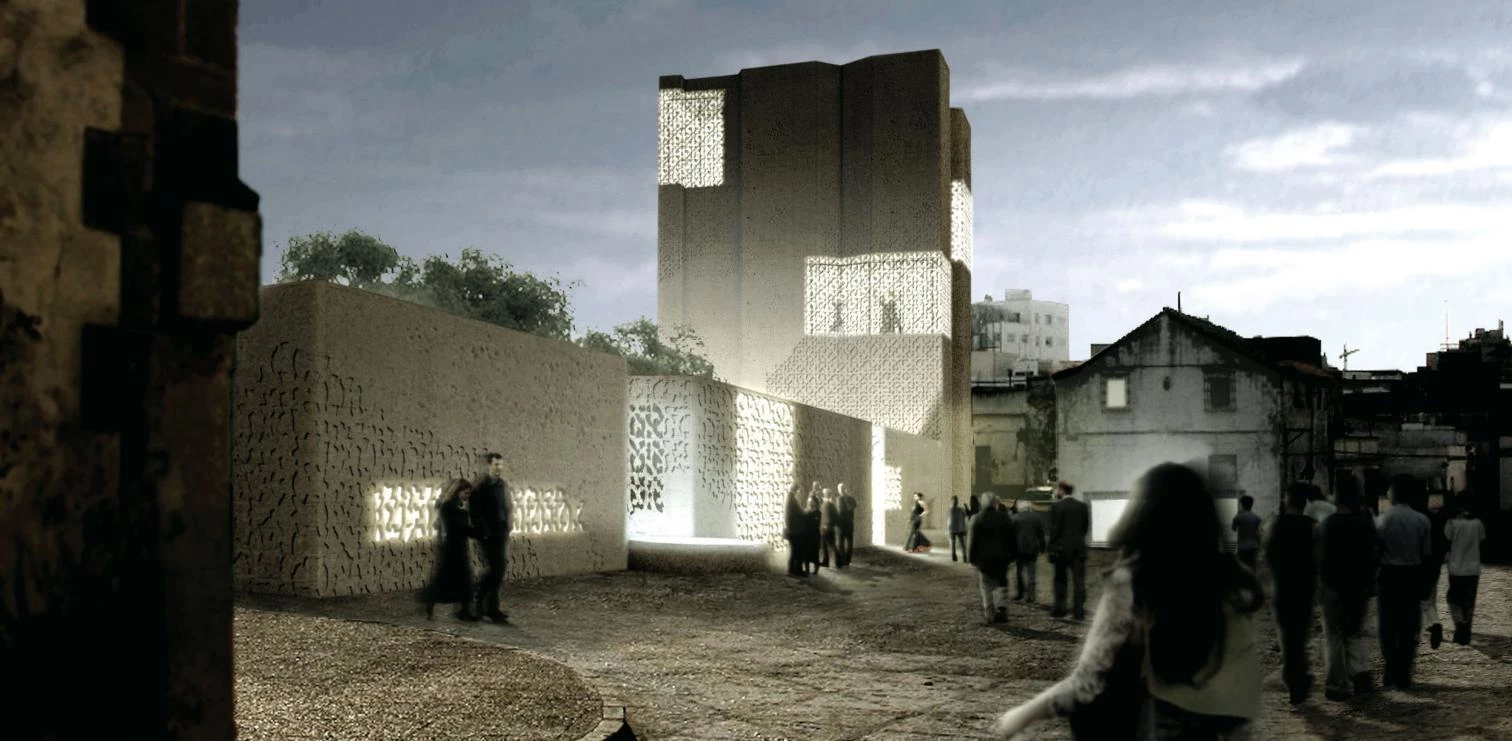

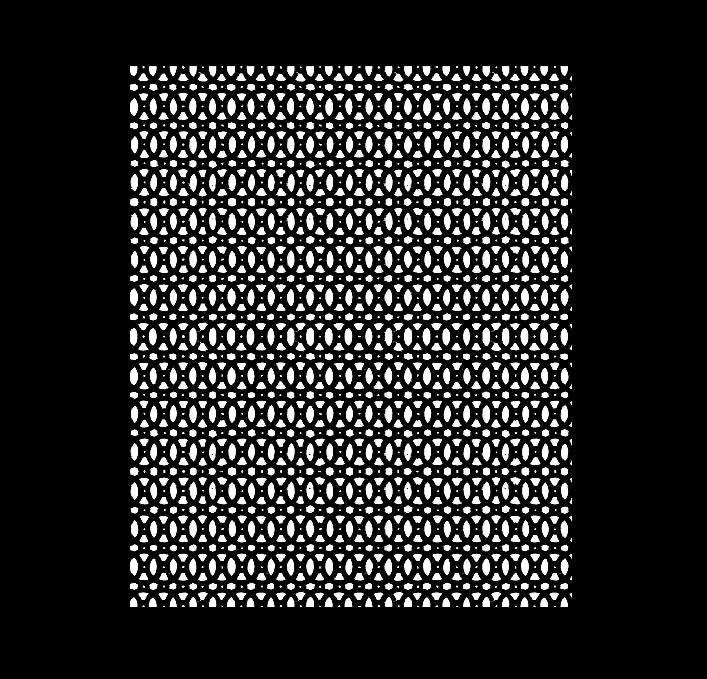

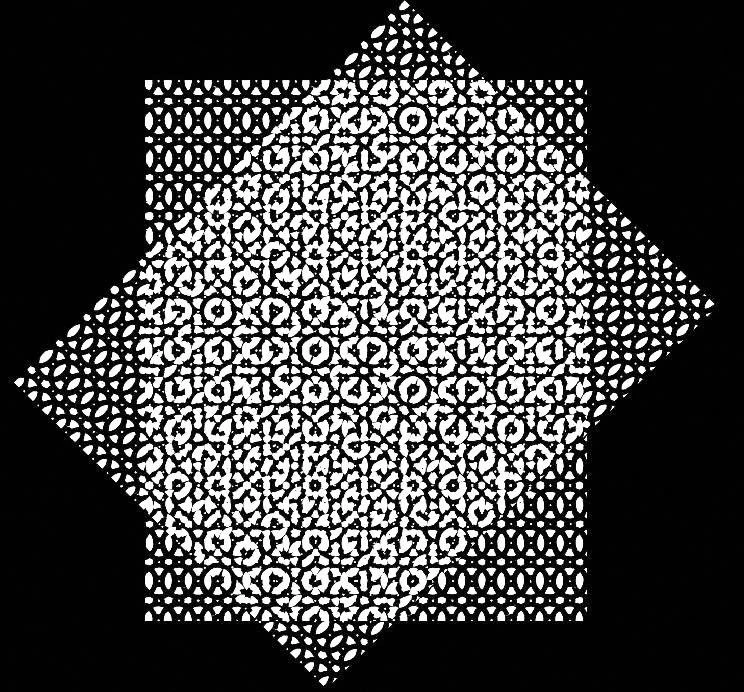

Tradition without folklore, emotion without tears, and ornament without pastiche: these are the wickers with which Herzog & de Meuron have braided the project for the City of Flamenco of Jerez. At once cultivated and popular, the proposal of the Swiss partners combines contemporary language and everyday life inside the walls of a garden of ponds and orange trees that joins roots and branches by weaving a warp of concrete and air over the woof of a historic city. In the cracked heart of the medina, a wall adorned with interference patterns – which every now and then become latticeworks – provides a guiltless decoration whose necessary and aleatory geometry reconciles Arabic-Andalusian imagery with urban graffiti, and this skin of cement, sensually scarified by the formwork and time likewise amalgamates the rhythmic roughness of flamenco with the tactile violence of tattooing. At once a mural and a tapestry, the luminous wall of the Jerez precinct is both tough and textile, grave and delicate, timeless and youthful: solidly rooted in its physical and symbolic place, and no less densely interlaced with its authors’ lines of material and formal innovation.

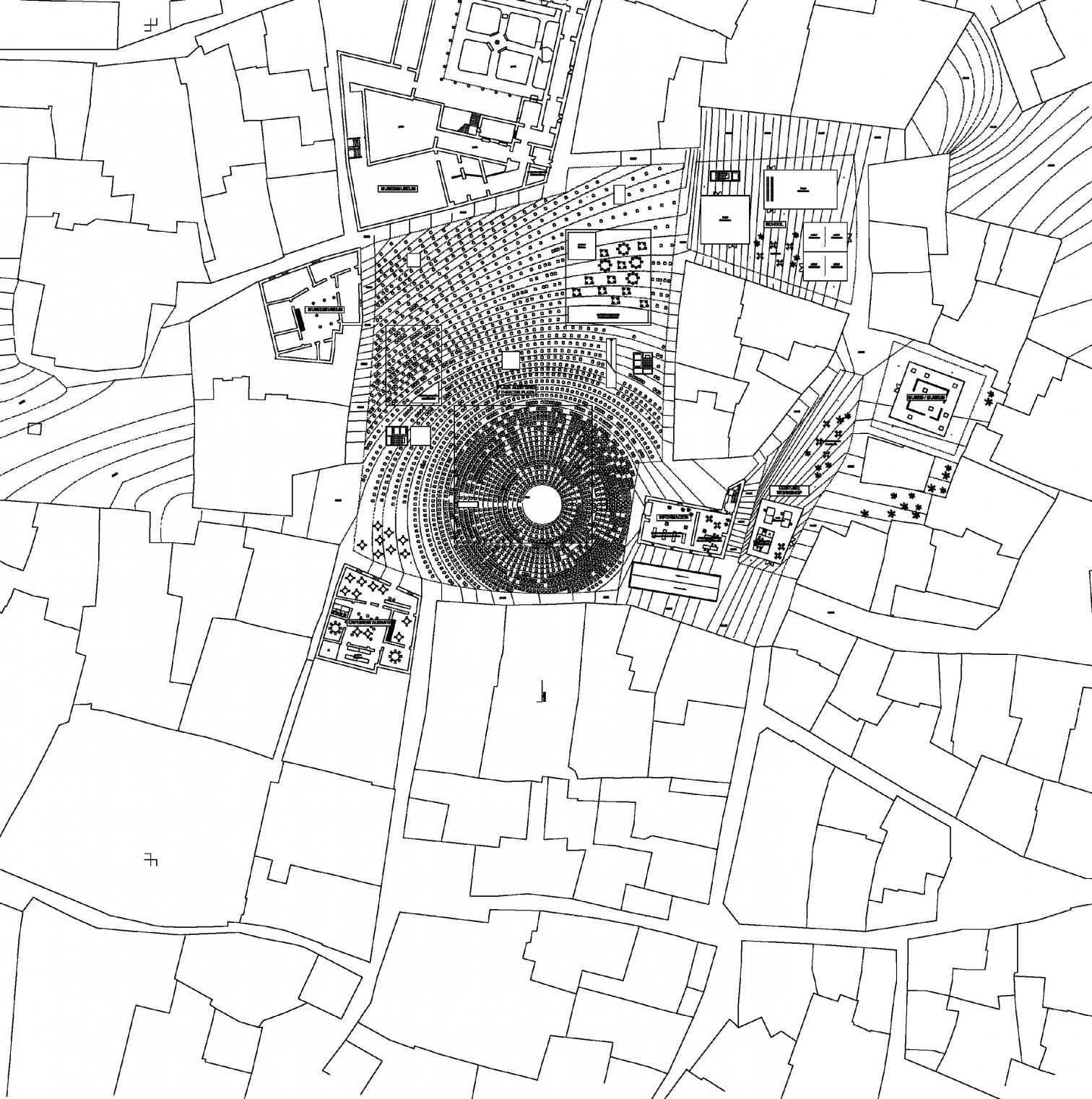

In the labyrinthian center of the old medina, the proposal of the Swiss encloses the program within walls that house secondary uses, pierced with vernacular-flavored latticeworks designed with interference patterns.

The City of Flamenco, a complex which is to include an auditorium, a museum, a school, and a documentation center, is an initiative of Pedro Pacheco, the charismatic politician who has been mayor of the city for 24 years, and it is to serve as a performance venue and reference center for the network of folk clubs and activities surrounding this unique art form, while contributing to the renewal of a decaying and progressively de-populated historic quarter. Invited to compete for the commission were two Sevillian teams with important works in Jerez (Cruz & Ortiz, who renovated its Chapín stadium, and Vázquez Consuegra, who designed its convention center); the painter and architect Juan Navarro Baldeweg, whose Canal Theater in Madrid is now in danger of being put on hold; the Japanese Sejima & Nishizawa, whose ambitious extension of the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM) is for the time being at a standstill; the Portuguese Álvaro Siza, who in association with Juan Miguel Hernández León is remodeling Madrid’s Paseo del Prado; and the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron, who with this new victory can add Jerez to a Spanish itinerary that already has stations in Barcelona, Madrid, Córdoba, and Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

Siza and Hernández León designed a sequence of articulated prisms and courtyards set in the urban fabric, rounded off by a trapezoidal piece cantilevered over the entrance, with a motion evoking flamenco dance.

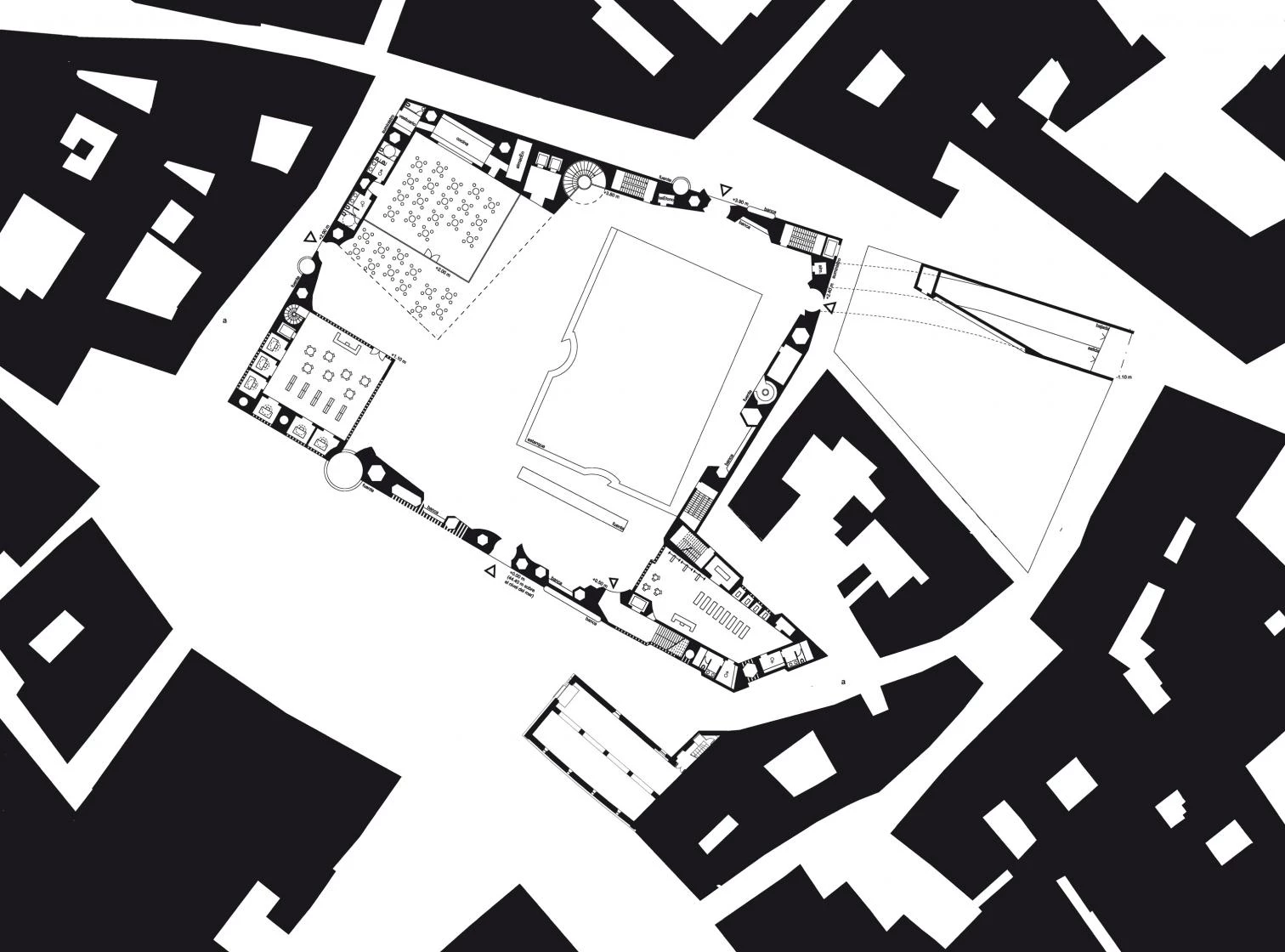

Located in the gravitational center of the precinct delimited by the old Almohad rampart, between two intramural quarters – San Miguel and Santiago – that are historic cradles of flamenco song, the cante jondo, and on the site of the convent of Belén (turned into a prison in the 19th century, and later replaced by a school that was demolished a decade ago), the competition for the cultural complex presented two difficult challenges: to insert a significant volume of construction in an urban fabric of modest buildings and narrow, labyrinthian streets; and to interpret in today’s language a program that, by its very nature and location, seems to inevitably lead toward the folkloric picturesque. Headed by Pacheco, and having as members David Chipperfield, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, Dominique Perrault, and myself, the jury opted to recognize the Swiss team’s tackling of both problems with a proposal that, without renouncing contemporaneity, blends well into the grain of the city and the visual memory of its inhabitants.

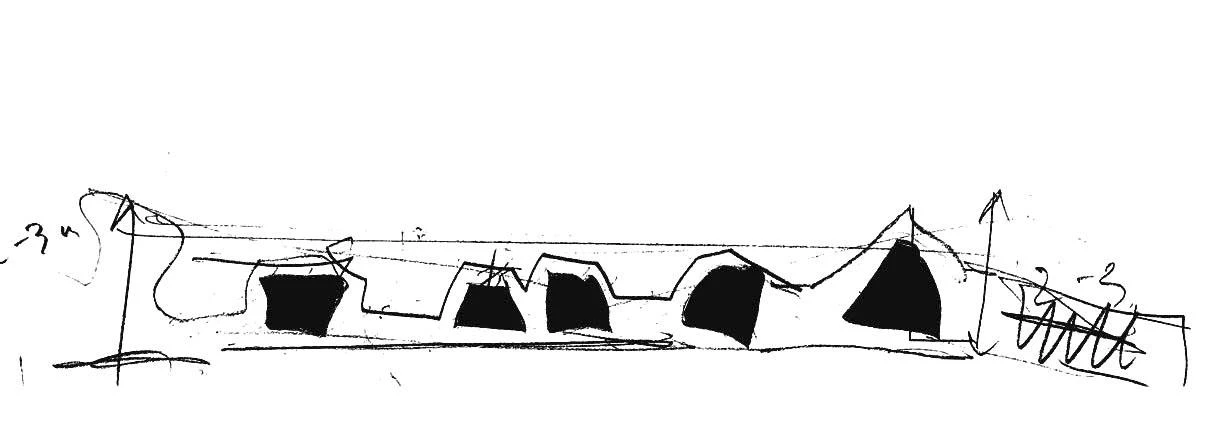

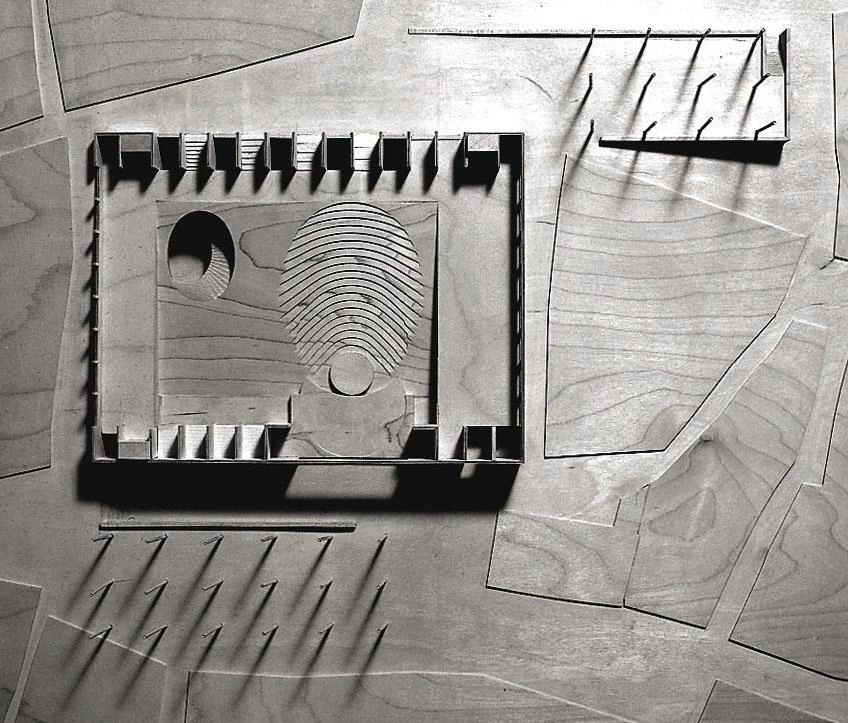

The other contestants adopted very different strategies, in all cases with a meticulousness and a level of commitment that can only be explained by the fascination that a heritage as that of Jerez’s old quarter provokes, and its populist vitality, that exceeds the clichés of flamenco, wine, and horses. The Andalusian proposals were almost antithetical. Cruz & Ortiz piled up the uses in a sober rectangular piece, well fitted in the immediate environment, with the school hanging in sawteeth over a sloping covered square, and with a version of the ‘total theater’ of Gropius over the underground museum to give shape to a stern and demanding project, with the floor plan of an exhibition pavilion and the look of a stone winery, halfway between the Rossian Moneo and the Sota of the Maravillas gymnasium. In contrast, Vázquez Consuegra took inspiration from the movements of flamenco dance to design a colossal building of concave facades, built with the dark iron of an ancestral pain that is lit only by violent flashes of blood in what amounts to an expressionist sarabande in red and black.

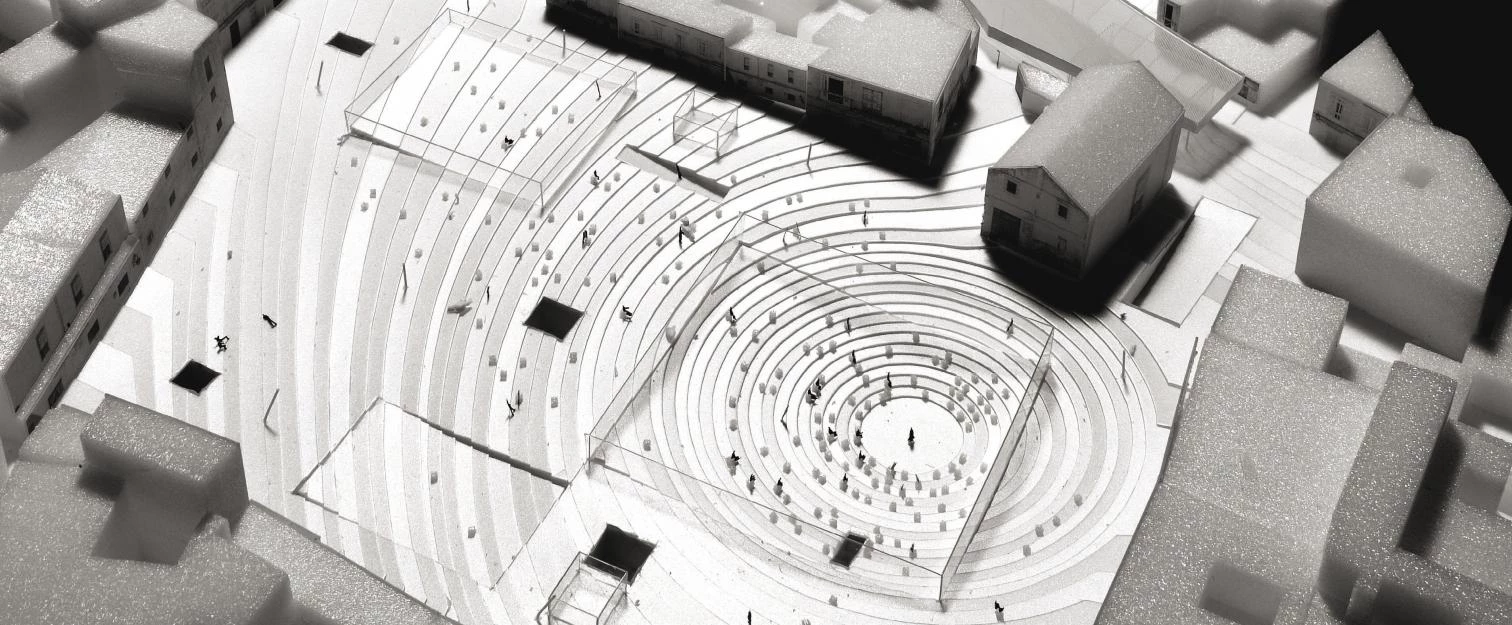

The bold enclosure by Cruz & Ortiz, the dancing shapes by Vázquez Consuegra, the golden cathedral by Navarro and the terraced crater by Sejima & Nishizawa address the context with different strategies.

Juan Navarro designed an exquisite volume of opaque and transparent glass, monumental and crystallographic like a dancing Stadtkrone, with large matt and milky planes framing fractured facades that reveal the amber and white interior like the luminous and angled transfiguration of a cathedral of stone and porcelain. Sejima & Nishizawa, in their turn, submitted the most radical idea, digging on the site to create an enormous terraced crater under a titanic reflecting roof, and proposing that the unlimited precinct protected by this vast geometrical steel cloud be at once a square and an auditorium, while all other uses be situated in surrounding constructions. Finally, Siza & Hernández León presented an assemblage of prisms and patios that are as intelligently articulated with one another and as elegantly inserted into the urban scheme as one can expect of the Portuguese master’s unmistakable calligraphy, wrapping up the laconic project with a sculptural trapezoidal piece, cantilevered over the entrance, that culminates the internal itinerary with a framed view of the cathedral over the old quarter’s clutter of roofs.

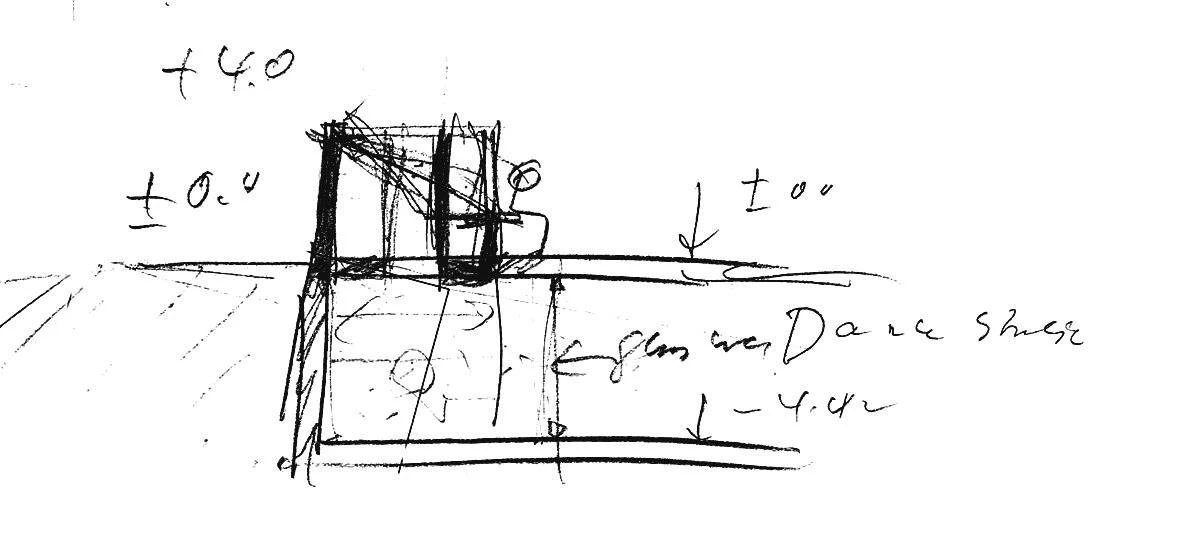

In the end it was the Basel office – represented in the public presentation of the projects by two of the partners, Pierre de Meuron and Christine Binswanger – that obtained the commission with its free and abridged version of Jerez’s Alcázar: a garden hidden behind a perimeter of walls that contain within them the staircases and skylights connecting to the auditorium and the underground classrooms, and a tower-lookout museum that rises by extrusion from the ground. A fortress and a paradise – in the traditional Islamic interpretation of the classical hortus conclusus – the Swiss proposal offers a public open space in the dense hub of the historic city, marked by the watchtower and built with a lace of geometric tracery and latticework that facilitates popular identification. This openly ornamental treatment that flirts with thematic identities and Venturian kitsch is certainly a tribute to the place, but it also results from a prolonged experimentation process that has brought Herzog & de Meuron from the basalt gabions of the Dominus winery – Cyclopean latticeworks in their own manner – to the rough creviced walls of the Schaulager in Basel, and on to the latest batch of pixelized skins in the museum projects for San Francisco and Tenerife. The subtly embroidered tapestry of walls of the City of Flamenco adds itself to this brilliant sequence, reaching an apex of emotion in Jerez that is hard to imagine for another theme and another place.

[+][+]