Solstice of Mies

Summer

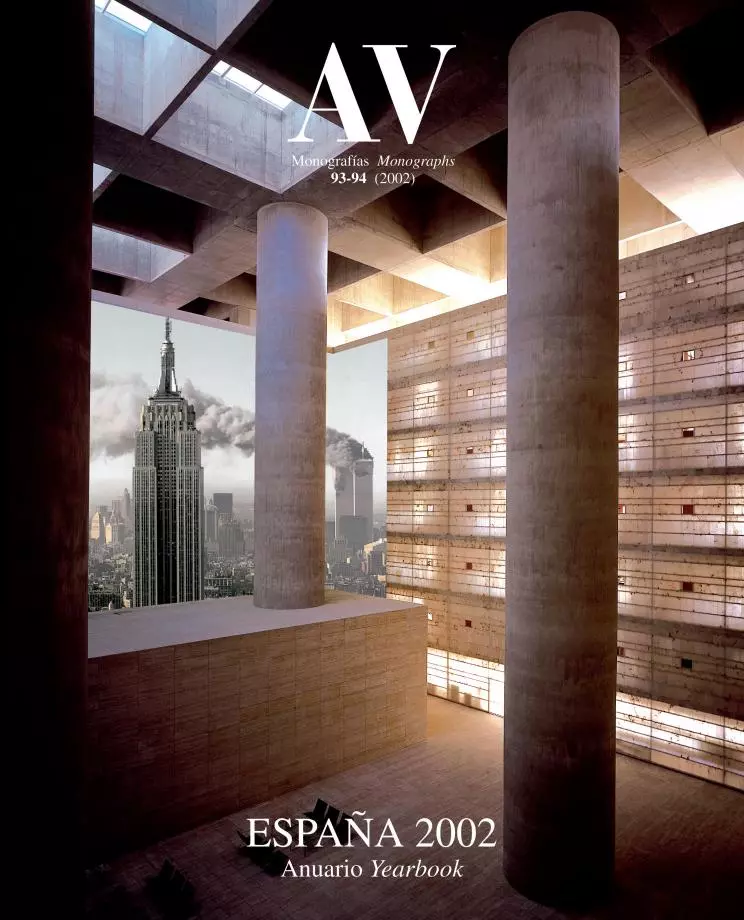

Less is more. For several generations of architects, the legacy of Mies van der Rohe – which currently may be having its heyday in critics’ as-sessments – was encapsulated in this minimal maxim. But theAmerican institutions that have united to revise the work of the modern master contra-dict such laconicism in the two major exhibitions that will be making Mies the star of NewYork’s summer. In the Museum of Modern Art, repository of his archive, Terence Riley and Barry Bergdoll present the first part of his career, from his arrival in Berlin in 1905 to the move to Chicago in 1938. In the Whitney Museum, which has worked in conjunction with the Canadian Center of Architecture, Phyllis Lambert focuses on Mies’s American experience, all the way to his death in 1969. Complemented by thick catalogs, a joint website (www.moma.org/mies or www.whitney.org/mies) and a seminar sponsored by the three centers to be held in September at Columbia University, the exhibitions ambitiously en-deavor to redraw the profile of one of the giants of the 20th century. The more is more approach of this rare inter-museum collaboration could nevertheless turn out as more is less, and more Mies may just end up being less Mies, because the master’s exigent rigor has been denatured by the mediatic racket of the event, and by the codicious frond of interpretations that, contradicting Gracián, seem to herald less quintessences than farragoes.

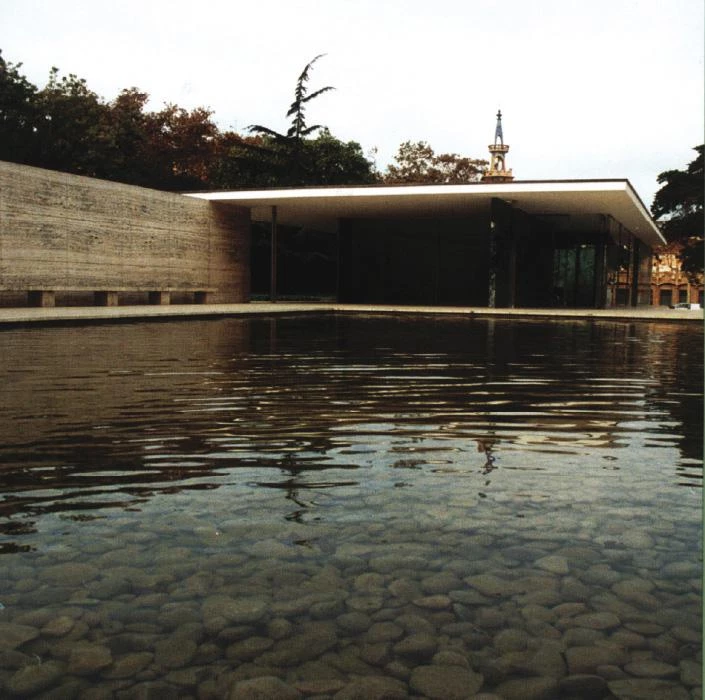

The MoMA announces its exhibition on the Mies of Berlin with a photograph by Kay Fingerle of the Barcelona pavilion (left); and the Whitney that of his Chicago years with the architect’s 1955 portrait by Irving Penn (below).

The MoMA exhibition documents 47 European projects of Mies through 288 original drawings and 14 new models, accompanied by videos of visual tours through the works, computer simulations, pe-riod photographs and recent shots, projects of hismasters Schinkel, Behrens and Berlage, paintings, sculptures and films by contemporaries like Man Ray and Duchamp, besides a photographic essay by Thomas Ruff and a digital kiosk dedicated to the avant-garde magazine G: a whole paraphernalia of media, objects and gazes that can enrich one’s knowledge of Mies, but also smudge the fundamental lines of his work with parasitic accretions, and conceal the vigorous traits of the personage under dispensable layers of commentary and gloss. When the curators assure us that this is the first-ever in-depth view of Mies’s early career, when they claim that the public’s cool response to the MoMA’s previous show on the architect – organized by Arthur Drexler in 1986 – was due to the hostile climate cre-ated at the time by postmodernism, then at its peak, and when they point out that the German master’s current popularity is manifested in works like Her-zog & de Meuron’s Dominus winery or Rem Kool-haas’ Bordeaux house, then we know that skepti-cism must prevail over enthusiasm

The Mies van der Rohe centenary fifteen years ago generated much unnecessary ruckus, but left in its wake at least two fundamental books, Franz Schulze’s critical biography and Fritz Neumeyer’s painstaking study on Mies’s writings and library. These two publications establish the rigorous features of today’s Mies canon, and are the references which any subsequent research must necessarily measure up with, no matter how much it claims to be first to discern depths. The MoMA, closely linked to Mies through Philip Johnson (who included his work as early on as the famous exhibition of 1932, and who in 1947 produced a retrospective and a catalog, both excellent), made a fiasco of that 1986 event, offering an exhibition that was mediocre and reticent. If that show was badly received, it was not so much for being out of tune with the postmodern temperature of the moment as for a lack of the modern conviction that is needed to present Mies. And the act of contrition to be expected of the museum cannot be replaced by naming the 1986 reconstruction of the Barcelona pavilion as the cause of Mies’s wide and diffuse influence on two successive generations of architects. This would put in Mies’s trail all those interested in transparencies or “nature, technology, and human consciousness,” from Herzog & de Meuron or Koolhaas to Reiser and Umemoto, making the German master an antecedent of anybody, and therefore of nobody.

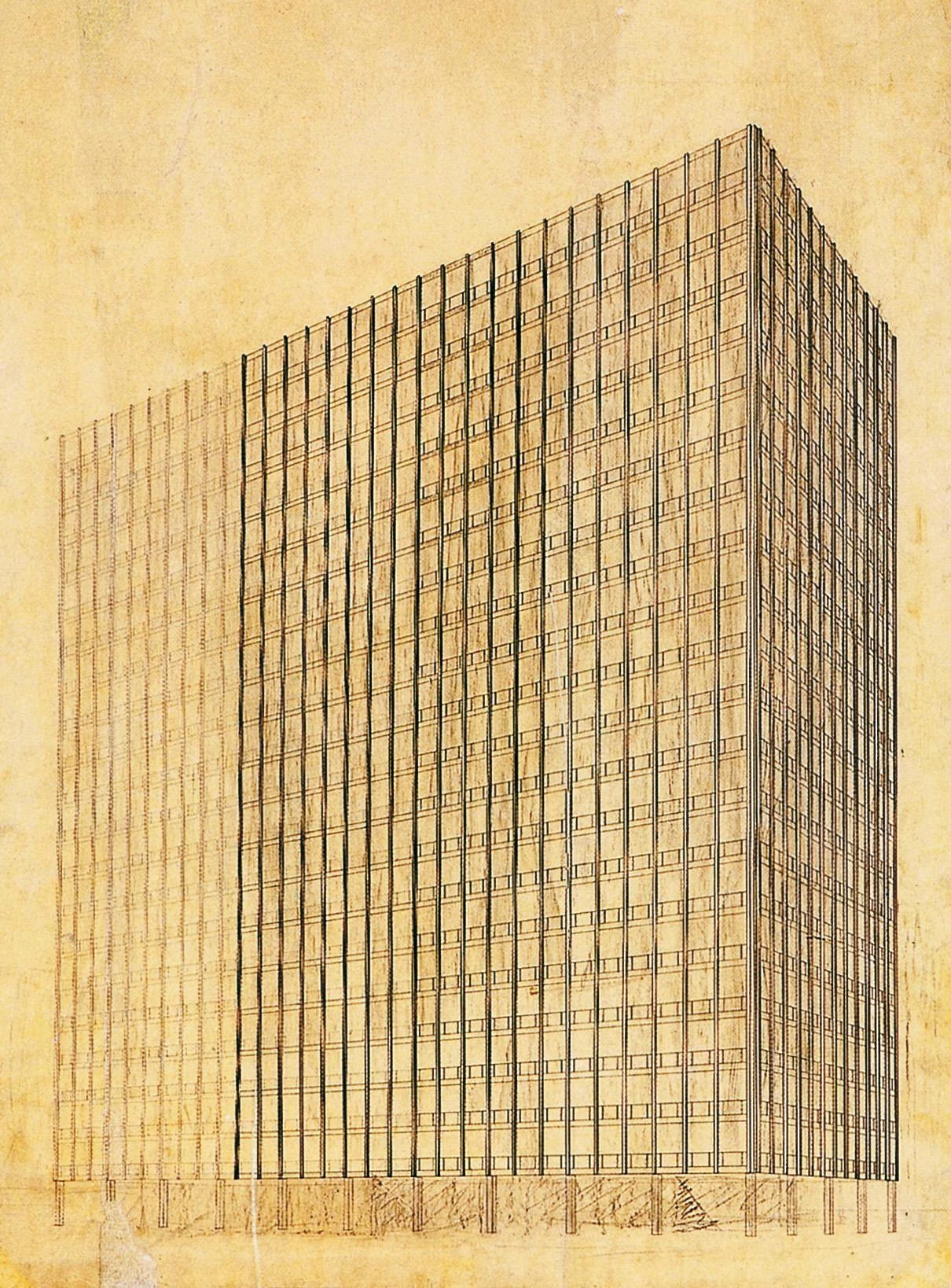

From the 1921 project for Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse (below, left) to the works carried out in the United States (below, right), Mies contributed to establishing both the final image and the constructive idea of the modern skyscraper.

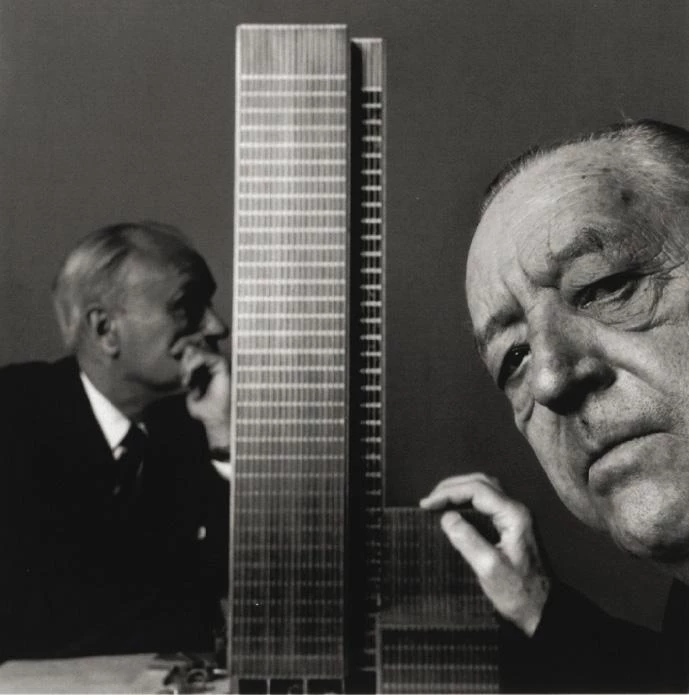

The photograph chosen as publicity for the exhibition is in itself a discouraging indication of the MoMA’s perspective. It is a picture of the Barcelona pavilion taken in 2000 by Kay Fingerle from the edge of the pond, adopting the viewpoint of an inquisitive frog. As it could be predicted, the shot grotesquely deforms the building, with no other ap-parent purpose than a trivial originality of focus. More promising is the image used by the Whitney: a devastating 1955 photo taken by Irving Penn for Vogue, in which we discern the wooden face of Mies, with Johnson in the background, and between them a model of the Seagram, the beautiful NewYork sky-scraper in bronze which Mies was commissioned to design by the president of the company at the re-quest of his daughter, Phyllis Lambert, curator of this exhibition, singular patron of the arts, and founder of the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal. The CCA will be the venue of ‘Mies in America’ come fall (17 October 2001 to 20 Janu-ary 2002), before ending its itinerary in Chicago (Museum of Contemporary Art, 16 February to 26 May 2002) whereas ‘Mies in Berlin’ will be in the German capital during the winter (Altes Museum, 14 December 2001 to 10 March 2002) and in Barcelona through the summer (CaixaForum, 23 July to 29 September 2002).

The photograph chosen as publicity for the ex-hibition is in itself a discouraging indication of the MoMA’s perspective. It is a picture of the Barcelona pavilion taken in 2000 by Kay Fingerle from the edge of the pond, adopting the viewpoint of an inquisitive frog. As it could be predicted, the shot grotesquely deforms the building, with no other ap-parent purpose than a trivial originality of focus. More promising is the image used by the Whitney: a devastating 1955 photo taken by Irving Penn for Vogue, in which we discern the wooden face of Mies, with Johnson in the background, and between them a model of the Seagram, the beautiful NewYork sky-scraper in bronze which Mies was commissioned to design by the president of the company at the request of his daughter, Phyllis Lambert, curator of this exhibition, singular patron of the arts, and founder of the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal. The CCA will be the venue of ‘Mies in America’ come fall (17 October 2001 to 20 January 2002), before ending its itinerary in Chicago (Museum of Contemporary Art, 16 February to 26 May 2002) whereas ‘Mies in Berlin’ will be in the German capital during the winter (Altes Museum, 14 December 2001 to 10 March 2002) and in Barcelona through the summer (CaixaForum, 23 July to 29 September 2002).

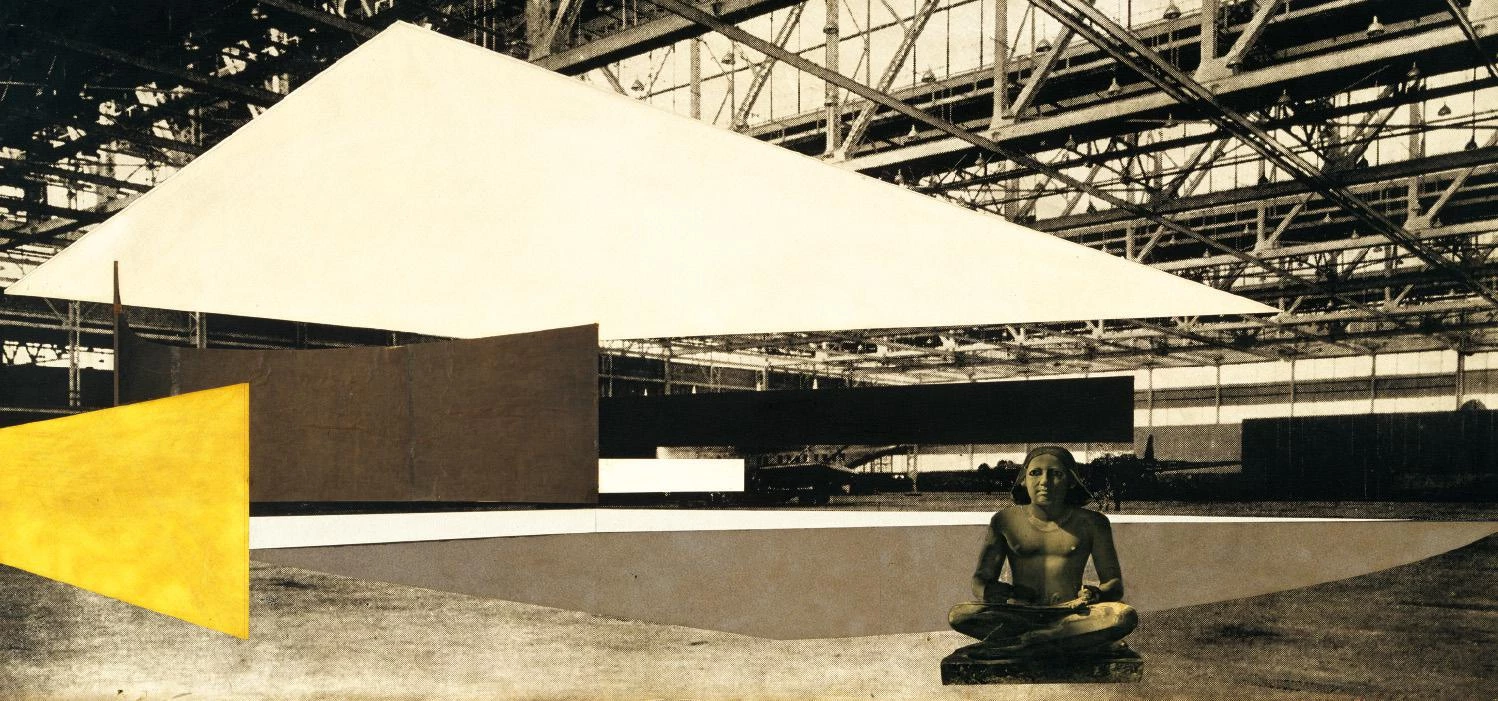

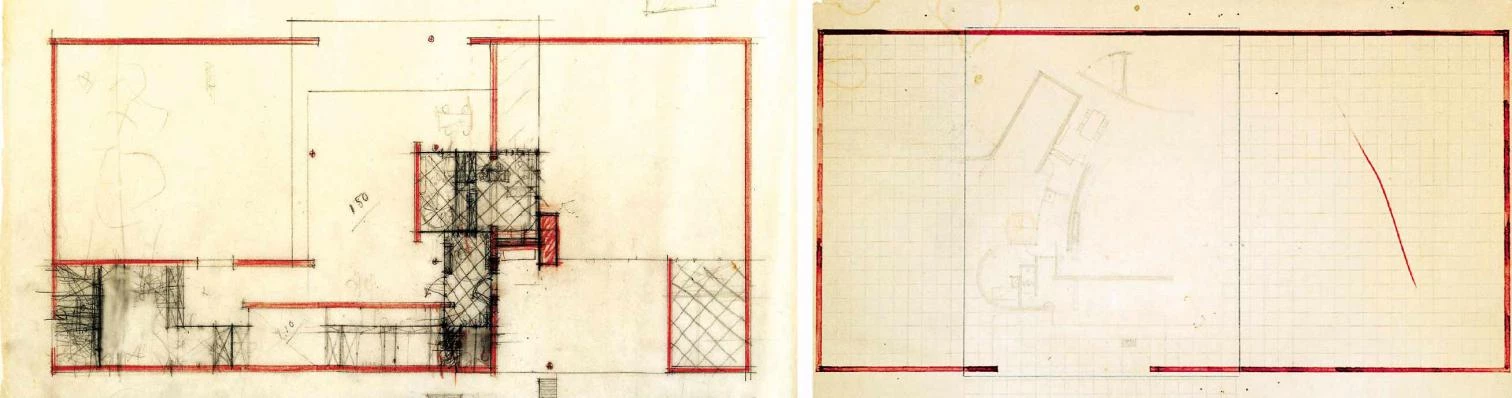

From 1937-1938 the first American project, the Resor house (below), rehearses in the domestic field the diaphanous configuration of the Auditorium from 1941-1942 and the Museum for a small city from 1940-1943

It is hard to make conjectures about what these efforts to reassess Mies’s legacy may lead to, but Idoubt there is sufficient new data to demand a significant revision of his historical importance. But we can in fact expect a renewed debate on his relevance or pertinence in current architecture, with special emphasis on his unbuilt projects, because it is there that the radical search of the architect reaches its most extreme and violent purity. From the expressionist and crystallographic fractures of the Friedrichstrasse office skyscraper to the implacable bureaucratic regularity of the most obstinate American prisms of the fifties, and from the unsurpassable neoplastic elegance of the brick country house of 1922 to the vertiginous dissolution of architectural space in the unbuilt Resor House of 1938 (Mies’s first American project, drawn up at the time of his move from Berlin to Chicago and thus the only design present in both exhibitions), the drawings, collages and photomontages of his unexecuted projects convey such intellectual energy and such emotional intensity that, more than his finished works, they deserve to be called “meditation machines”, the name coined by Richard Padovan. Here the sumptuous steel-and-glass minimalism we commonly associate with the architect gives way to the spiritual passion of the reader of Romano Guardini or Rudolf Schwarz, and the reduction of architecture to a construction that expresses the nature of materials retires in favor of a transcendental and metaphysical quest for architectural truth through a negation of form. Here too, perhaps, less is more, and Mies’s zenith coincides with his nadir.

The court-house emerged at the Bauhaus as an exercise, later proposed by Mies to his Chicago IIT students. Far left, Court-House with Garage (1934) and Lange House (1935), two variations of the original scheme.