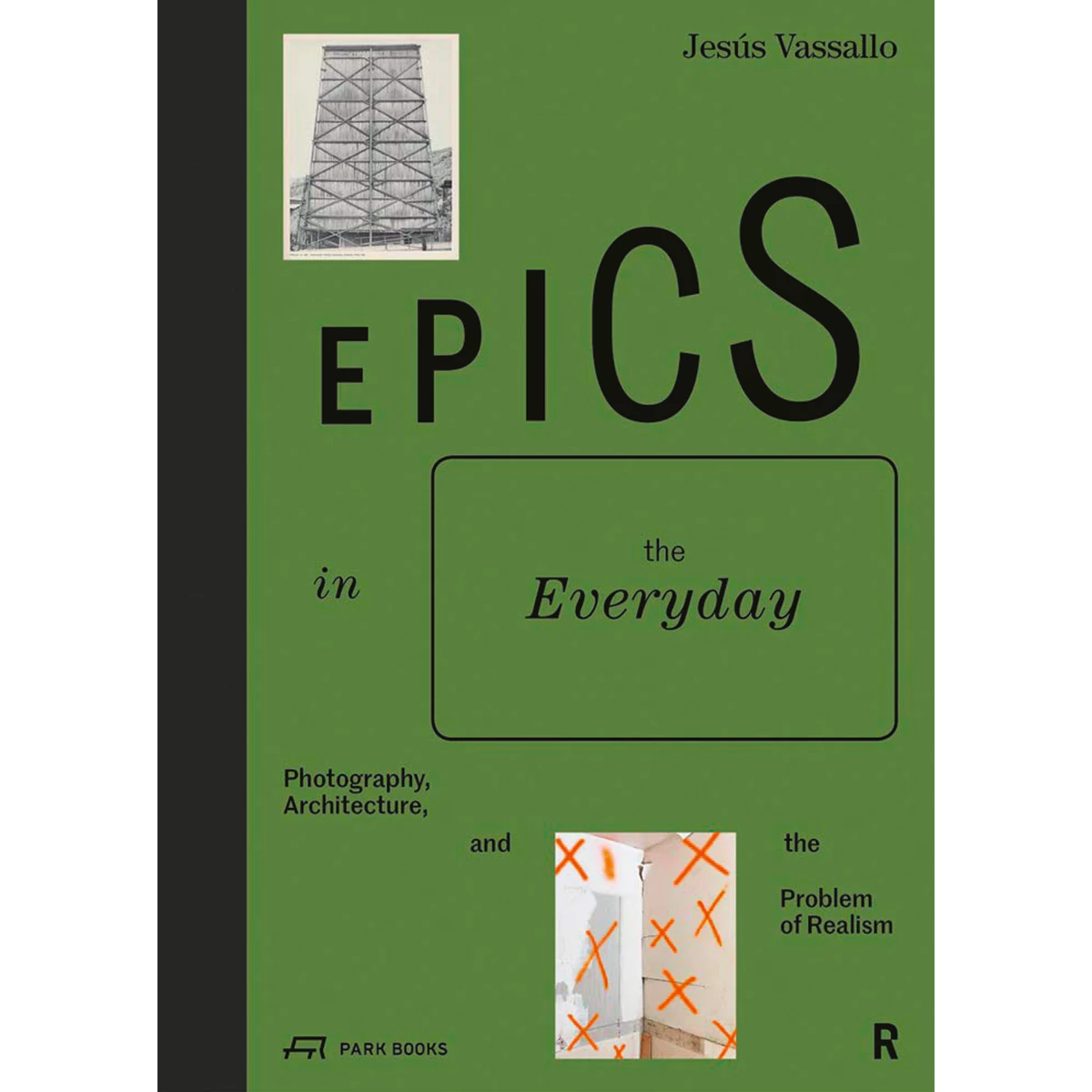

The inevitable presence of reality in architecture and photography alike is ultimately the main reason why a parallel discussion of both disciplines is productive and necessary. Philip Ursprung’s suggestion of a realist current in contemporary architecture led Jesús Vassallo to question the generalized architectural discourse that exclusively links realism in architecture to vernacular historicism, and to propose a version where photography, in its progressive confrontation with the social realm, has a more powerful and stimulating influence. It is through the realist trend that the two arts engage in dialogue, interweaving references and theoretical constructs in the course of the 20th century and fusing in the final decade. The argument presents four case studies in a timeline where architect and photographer seek to “dismantle obsolete cultural constructs by systematically exposing more disturbing yet simultaneously more accurate images of reality.” The examples fall in two stages, divided by the appearance of conceptual art as a historical bookmark and flanked by an introduction and a closing reflection.

The first period begins with photographer Nigel Henderson’s promenades – later guided tours – through the East End in London’s Bethnal Green. These wanderings of discovery, in search of a photographable reality that transcends a documentary context, draws the attention of young Alison and Peter Smithson, and they all together develop a new attitude to art and life. Here appears a subversive desire to find a deviation from dominant discourses, and this becomes evident in studies undertaken by Venturi and Scott Brown, who, inspired by Ruscha’s cavalier photographs, develop an influential critique of the Modern Movement in Learning from Las Vegas. In this postwar period, hence, two semi-autonomous disciplines – photography and architecture – cross paths at a moment of “cultural consumption and appropriation” on the part of architects. In the 1980s and 1990s, the incursion of conceptual art, which borrowed much from photography and architecture, brought on the second stage of the narrative, in which the techniques are transformed, as much in themselves as in their interrelationships. Rossi’s works and the images of the Bechers now mark a meeting point brilliantly materialized in the collaboration, first, of Thomas Ruff with Herzog & de Meuron, and later of Thomas Demand with Caruso St John. If architects once borrowed from artists who had discovered the wrinkles of reality, the two disciplines now take from one another to manifest and exploit them.

In a reduction and abstraction process similar to that of the book’s protagonists, Jesús Vassallo deconstructs both disciplines and then reconstructs them within a new theoretical imagery. This throws light on the photography-architecture bond by means of a realist current that bridges the gap between architecture and the built environment.