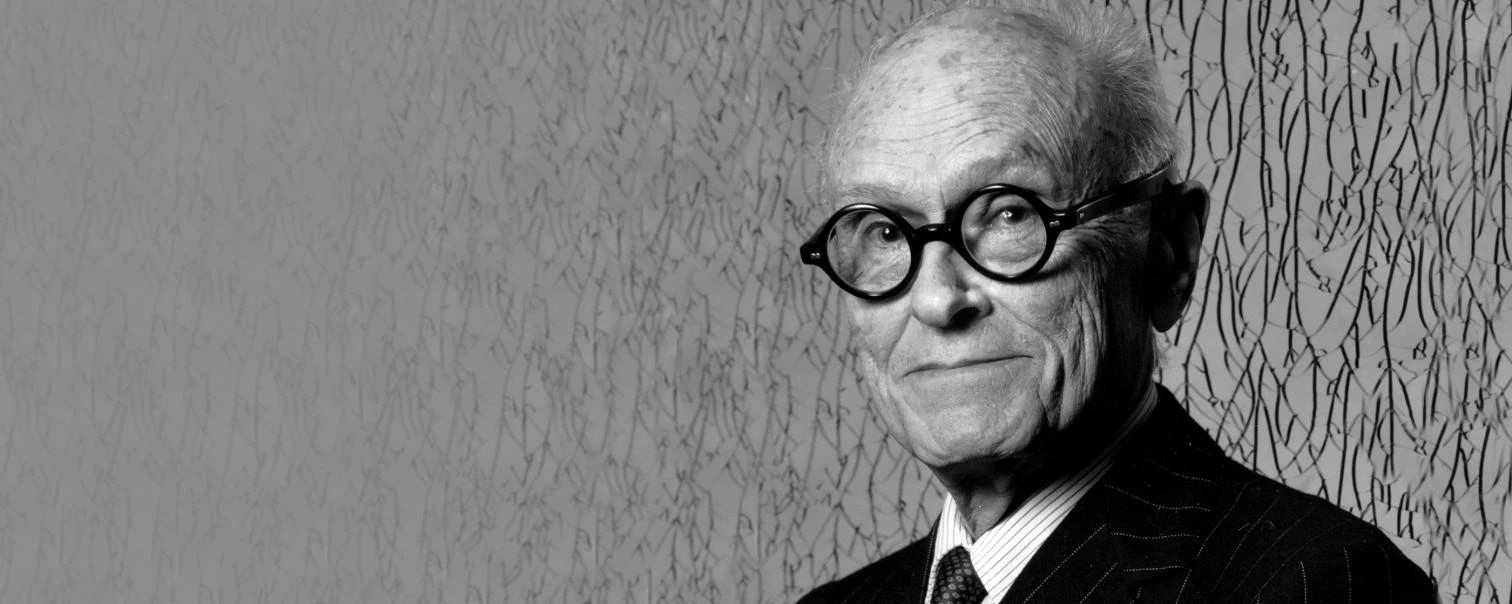

(1906-2005)

Philip Johnson’s life almost perfectly spanned his century, the 20th, many of whose architectural chapters cannot be discussed without mention of his omnipresent figure. Born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1906, he studied humanities in Harvard and discovered modern architecture on a trip to Europe. Named director of the MoMA’s architecture department in 1930, in collaboration with Henry-Russell Hitchcock he organized “The International Style,” the 1932 exhibition that opened the doors of the United States to the avant-garde of the old continent and gave a name to subsequent developments of that modern seed in America. In 1943 he returned to Harvard to study architecture with Gropius and Breuer, and in 1949 he finished the Glass House, an all-glass structure that manifested his devotion to Mies van der Rohe. He took part in the latter’s project for the Seagram, whose Four Seasons restaurant was for Johnson a kind of second office from where to orchestrate changes of tastes and tendencies in the course of five decades. His career touched almost all the century’s “isms”, going through a classicist phase that left us works like the Lincoln Center (1960-1964), a postmodern period marked by the tower for AT&T (1978-1983), and a deconstructivist stage represented in Spain by the leaning towers of Plaza de Castilla in Madrid (1991-1995), which he built with his then-partner John Burgee. This last stylistic swerve, inspired by the Russian avant-garde, was sanctioned through another MoMA exhibit that Johnson curated, with Mark Wigley, in 1988. But the best summary of his eclectic career and his shifts of aesthetic sensibility is perhaps the series of structures that he went about adding to his estate in New Canaan, the place where he built that first glass prism and where he died at 98. Other works that bear his signature and that earned him the Pritzker in 1979 are the first extension and garden of the MoMA, the towers at Pennzoil Place in Houston, and the Glass Cathedral in Garden Grove, near Los Angeles. Retirement did not consign Johnson to oblivion. In his last years he spoke openly of his homosexuality and apologized for the Nazi sympathies of his youth. In 1994, Frank Schulze, the same biographer of the Mies he so admired, published an account of Philip Johnson’s life that manages to present a truly personal dimension of the master.