Scottish Inquiries

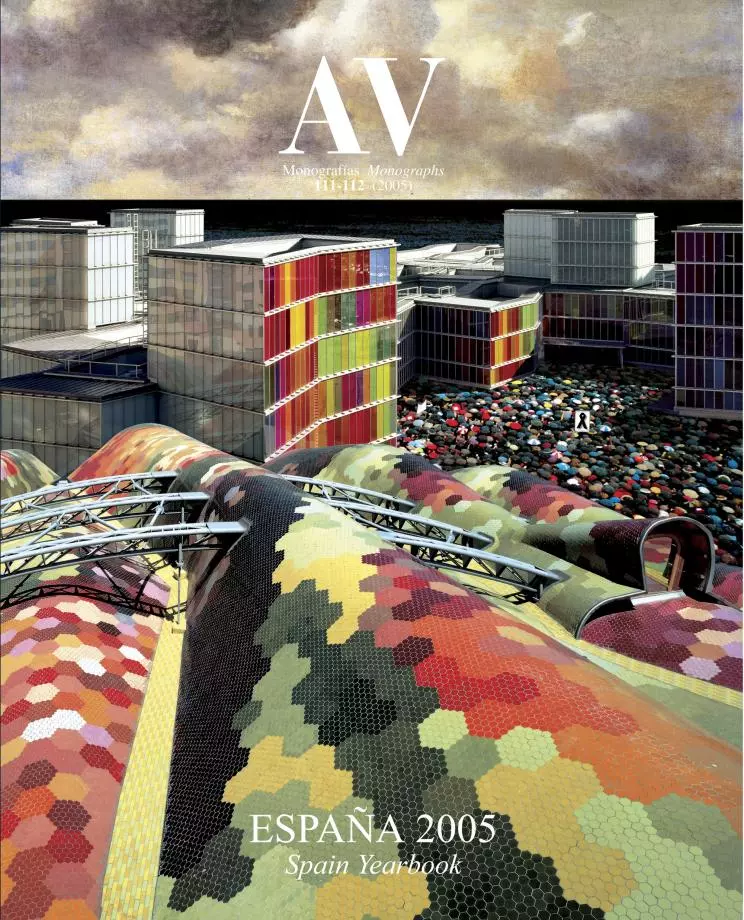

The Scottish Parliament, a work by the disappeared Miralles, has opened with praise for its lyrical language and controversy for its budget overruns.

Lord Fraser differs from Bismarck. Whereas the German chancellor deemed it best not to know how sausages and laws are made, the British Parliament, in the tradition of democratic transparency, has conducted a survey to shed light on the construction of the building where Scottish laws will be made, specifically on how a work initially budgeted at 60 million euros has cost over 630 million euros. Reading the report – a 270-page book put up for sale, at 15 pounds Sterling, on 15 September – makes one wonder if it would not indeed be preferable, after all, to ignore how sausages, laws, or buildings are made, and especially the buildings where laws are cooked up and which, precisely on account of that circumstance, manage to take shape in legal dark zones. After several months of court appearances that have made the Holyrood Inquiry a stream of scandalous revelations, both on TV and in the newspapers, Lord Fraser’s well-balanced report is as illustrative and entertaining as it is disturbing: this exercise of democratic transparency shows the extreme inefficiency of and waste incurred by democracy itself.

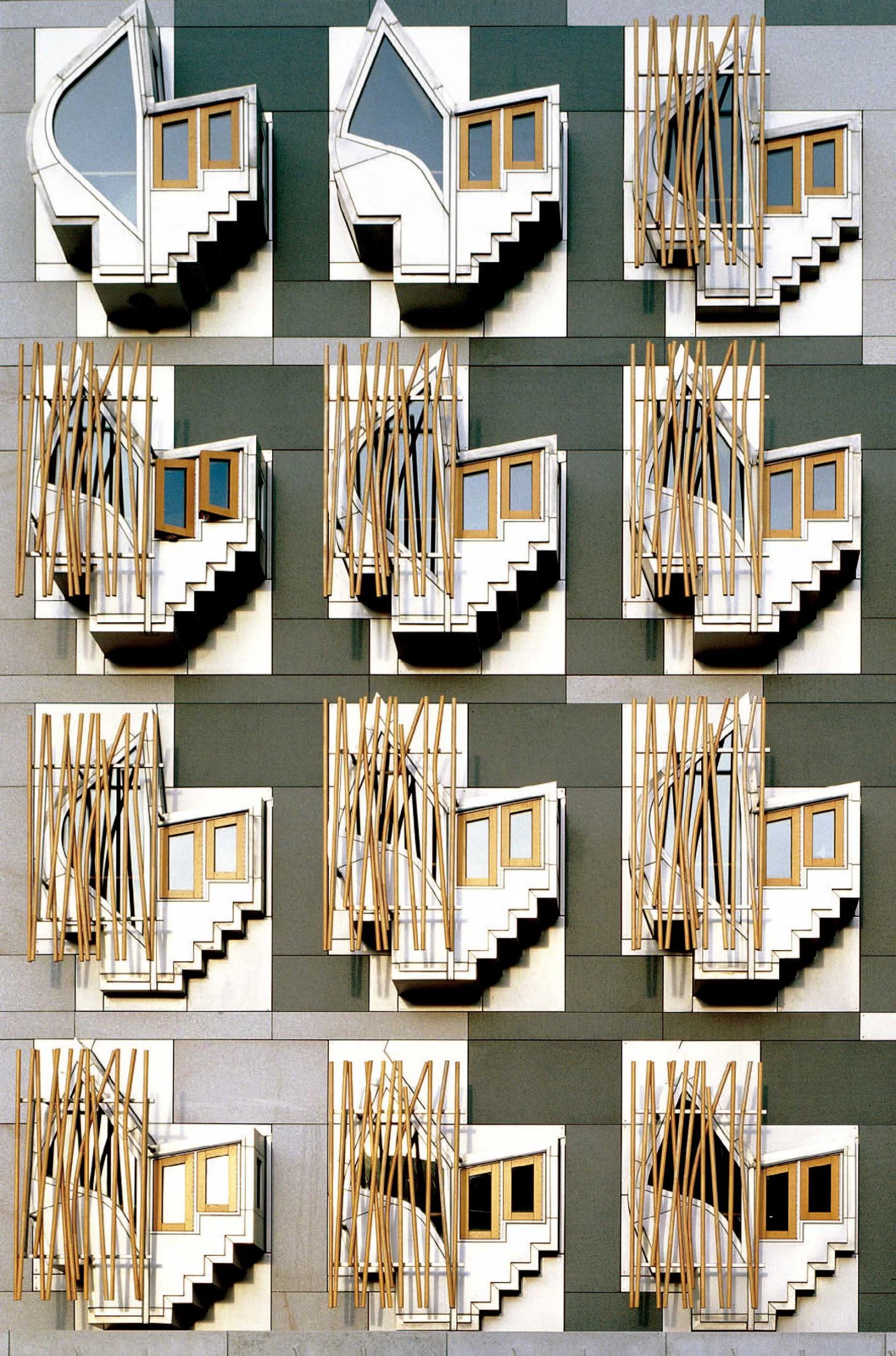

The calligraphic design of the idiosyncratic windows, that have become abridged symbols of a fragmented work, has also been a source of user criticism for the lack of consideration given to the rather scarce light of Scottish lands.

Enric Miralles, the author of the project, passed away in 2000. So did Donald Dewar, the project’s enthusiastic promoter – first in his capacity as Scottish minister within Britain’s Labour government that set the bases for autonomy, and as Scottish Prime Minister after the first legislative elections. How easy it would have been to blame the dead architect and client for the delays and the financial recklessness that have multiplied the parliamentary seat’s cost tenfold. But the report deplores the evasion of responsibility manifested by practically all the deponents – actually, Lord Fraser assures us that “It wis’nae me” was the common denominator of the hearings – and avoids naming scapegoats, preferring to spread out its censures ecumenically. Evaluating in fair terms the cost increases provoked by the enlargement of the building’s usable floor area by a third, or by the additional security measures deemed necessary in the wake of 9-11, the main reproach of the report falls upon the contracting method used – a fast-track system that, in the name of a paradoxically ill-attained speed of execution, makes the final drawing up of the project overlap with the successive tenders of the job itself, thereby keeping the budget in a permanent state of revision. But neither the politicians responsible nor the architects are spared chastisement.

Aspiring to become “the most important patron of the architecture of government for 300 years”, ever in search of quality, Dewar approved all the changes and cost increases, as would the Scottish Parliament commission that later replaced him in the role of client, a group of MPs with no experience whatsoever in building projects. The studio of Miralles, in turn, appears in the report as having been ill-fit to address the demands of a work of such a scale and complexity, and in constant conflict with RMJM, the Edinburgh office it was associated with. The Architects’ Journal reports on how both Benedetta Tagliabue – Miralles’ widow, who now heads his practice – and the directors de RMJM, after testifying in court, received written word from Lord Fraser warning them ahead of time that they would be objects of censure in the public report. The Tory MP sourly laments the BBC’s embargo of the interviews that were made with Dewar and Miralles for the as yet unreleased program The Gathering Place, and that could have served as testimonies of the two deceased protagonists. In his opinion, nothing sums up his report better than a handwritten note, dated March 1999, of the consultant Ian McAndie: “Nobody tells Enric to think about economy with any seriousness.”

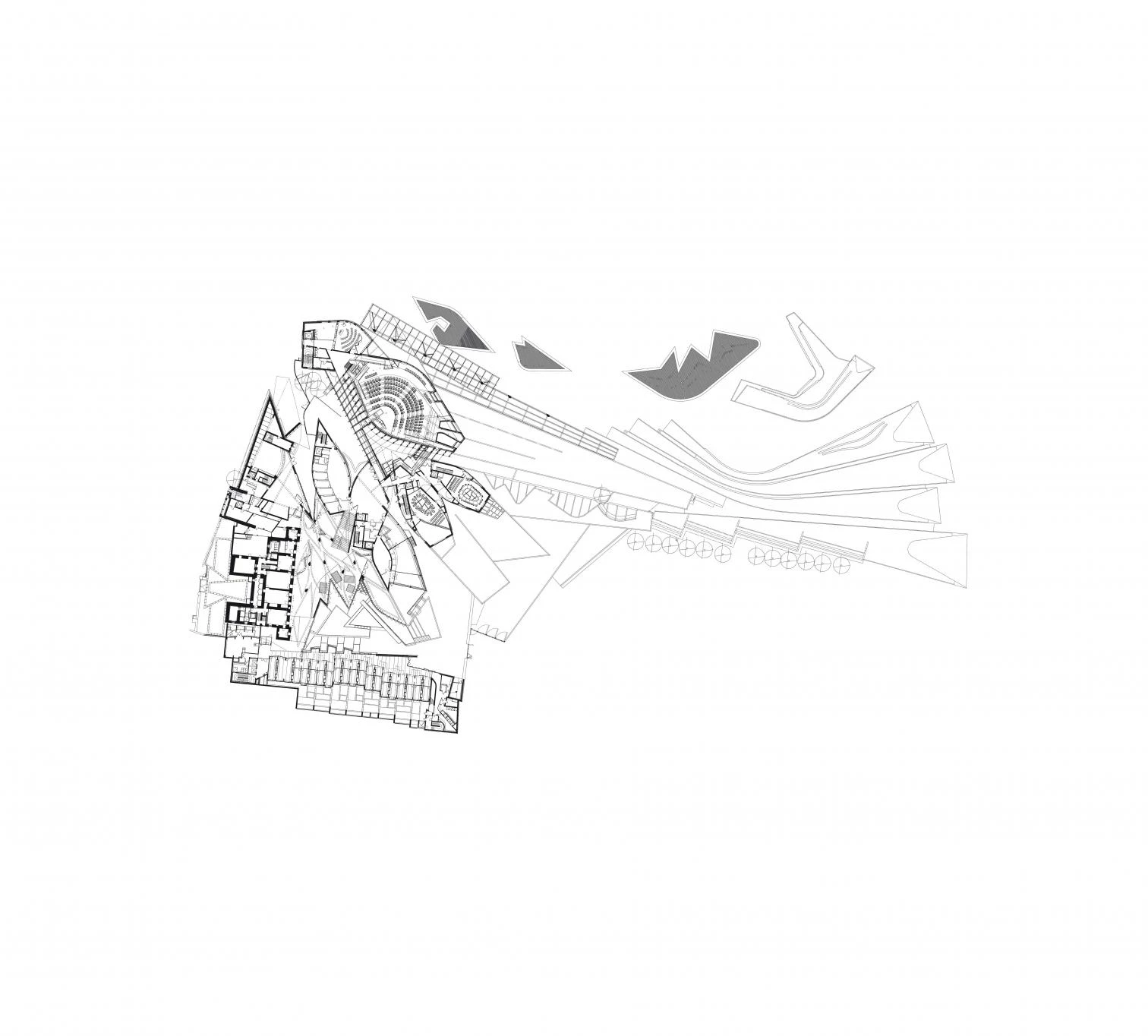

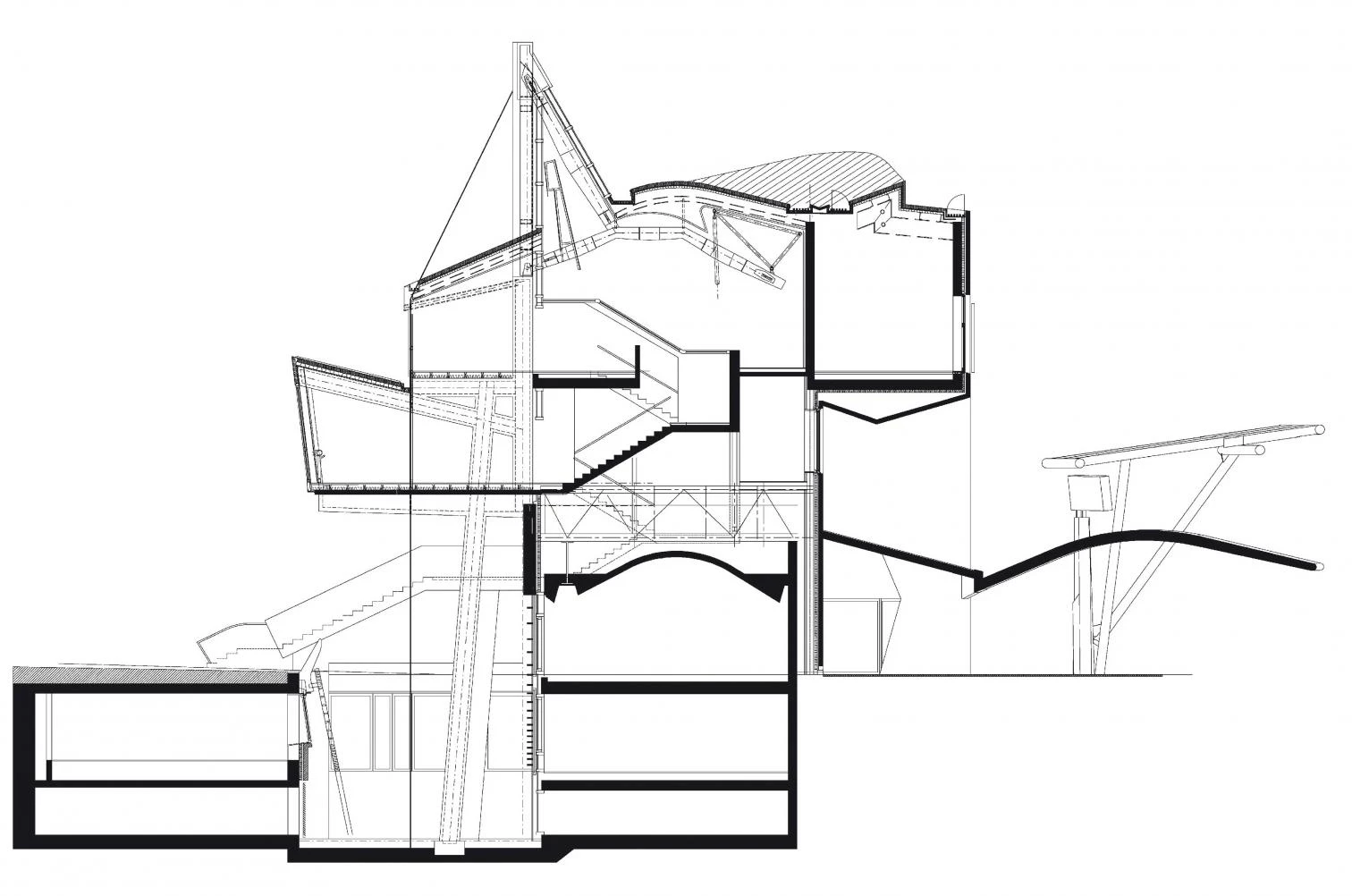

The fractured volumes of the Scottish Parliament blend into the historic center of Edinburgh with a choreographic spirit which is also present in the extreme articulation and frozen movement of the warm interior spaces.

The climate of opinion in what is already a cause célèbre is perhaps reflected in the diagnosis of a Scottish MP, Margo MacDonald: “There was a faint rosy aura around all things Catalan and up pops Enric, who was a charming man. But it was a shame and a disaster that he was chosen as architect, and it was possibly a scandal as well.” In this atmosphere of indignation, the critics attacked on the most disparate grounds. Defenders of heritage regret that Parliament is not a historic construction like the Assembly Building of the Scottish Church. Local businessmen deplore the French wood, Chinese granite, and Japanese steel, all contrary to the initial promise that Scottish materials would be used. And the members of parliament moan the lack of flexibility of the floor plan, the excessive concrete of the claddings, and the darkness of the offices, lit as these are by calligraphic windows that have become the project’s most characteristic feature but which the building’s users deem to be more suitable to the intense light of the Mediterranean than to the climate of Scotland. When the building got flooded at the end of August, making it necessary to vacate the police offices in the basement, the cartoonist Hellman grabbed the opportunity to playfully recall the metaphor of capsized boats that had originally inspired the project, and that now is inevitably associated with the economic and functional sinking of the parliamentary boat.

The symbolic lightness of the original project had to adjust, through a lengthy process of redesign, to the security measures imposed after 9-11 in public buildings, including heavy walls to protect from impacts.

Lord Fraser’s report is emphatic in declaring that it does not make aesthetic judgments, recalling that the decision of the jury that selected Miralles in 1998 was unanimous, and offering examples of emblematic projects that were controversial while under construction only to become universally accepted icons on completion. It also stresses that the main confrontation of a symbolic nature that came to pass between the architect and the client, having to do with the shape of the chamber, did not have significant repercussions in the cost. Miralles preferred an arrangement of the seats in an open curve resembling a bow because, as he stated in capital letters in his first brief, “the seats of Parliament are a fragment of a larger amphitheater where citizens can sit in the landscape,” whereas the MPs demanded a horseshoe that would enable them to look at each other, making it necessary to reach a compromise with an intermediate shape. Tagliabue brings up these intentions describing how they wanted to relate the work to nature and the city, thus avoiding both the centralized parliamentary models put forward by Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn and the more recent representations of democracy with emphatically transparent buildings.

The present head of the Barcelona firm tells the magazine Diseño Interior that the public enters the parliament from the square of Holyrood Palace, whereas the politicians come in through a higher level. In this way, they cross each other but never touch. “The day the Scottish people want to protest,” she adds, “they will be able to do so in the public amphitheater that we have built at the foot of the Parliament.” The contents of Lord Fraser’s report may well give them reason to do so, with its sordid details of endless struggles over fees and its accounts of ludicrous episodes like the designation of the deceased Miralles as the project’s ‘principal person’ with ultimate responsibility for decisions made in the course of its execution. But just as the emotion of art is independent of its price, and just as the artificial prolongation of a formal language as unique as Miralles’ is doubtful, we are not sure we want to know everything that takes place in the opaque labyrinths of creation or politics. Without sparing praise for that exemplary exercise of Anglo-Saxon democracy that the Holyrood Inquiry has indeed been – the report ends with a laconically humorous note saying that it was delivered in keeping with the foreseen budgets and deadlines –, perhaps we must also recognize Bismark’s wisdom when he recommended blissful ignorance in matters of edible innards and the innards of power.