Ancient Mandarin had no word for ‘architect.’ Builders were craftsmen, skilled but unschooled folk who did not mix with erudites and elites. So in China it took time for Western-style architectural practice to take root, through the decaffeinated modernity of architects trained abroad and returned to raise buildings in steel and concrete but crowned with pagoda-like roofs.

Up to the country’s economic boom and its new open door policy consummated with the Beijing Olympics and the Shanghai Expo, there was no fully modern architecture in an ‘official’ sense. When it came, it was only through great international stars, who then gave us a picture of China that was as incomplete as that of a rich gastronomy reduced to chop suey. But in the last two decades a young crop of Chinese architects has altogether redefined the discipline through a balance between age-old roots and a contemporary spirit.

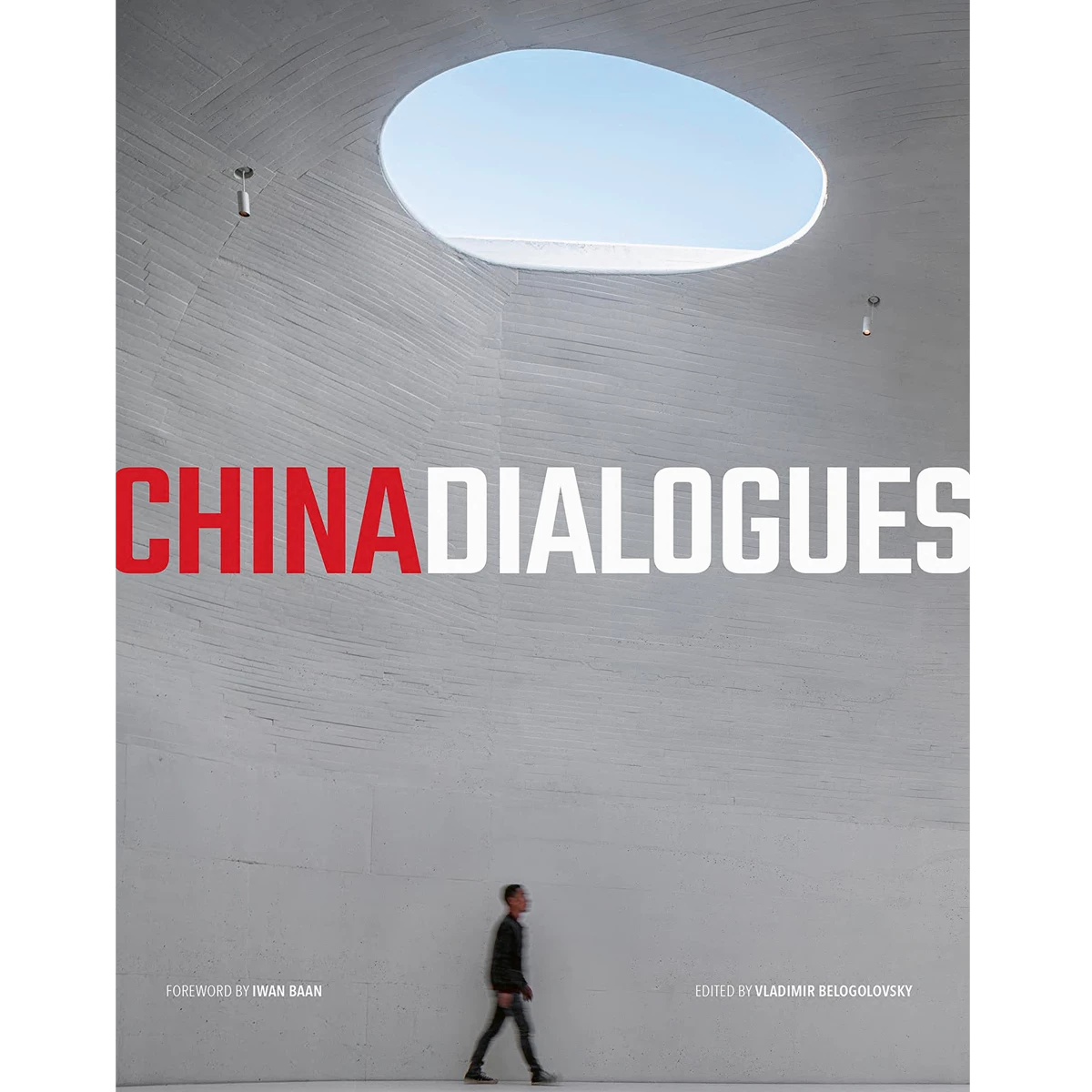

Belogolovsky has met many in his trips to China, and now presents extracts of conversations with 21 of them. Not one downplays their western training (only 9 have not studied abroad), but all stress the role of local schools and institutes, which they credit with reawakening an awareness of history.

From Wang Shu to Ma Yansong or Zhu Pei, a whole generation sits down with the Ukrainian-born critic to tell of how, amid brutal urban growth and globalized uniformity, it opts to regenerate traditional materials and techniques. An attitude bound to give full meaning to the word ‘architect.’