It is no easy task to write a short account of Ventura Rodríguez’s life, even with biographies ranging from the first one by Pulido and Díaz to last year’s publication by Juan Manuel Moreno. We know that he was born in Ciempozuelos in 1717 into a modest family of journeymen, and that he died in Madrid in 1785 as Spain’s renowned restaurador del arte clásico. But little is known about his personality, conduct, and private life. His fame and artistic legacy fundamentally consists of a truly prodigious output: hundreds of enquiries, reports, drawings, projects, and works carried out all over Spain.

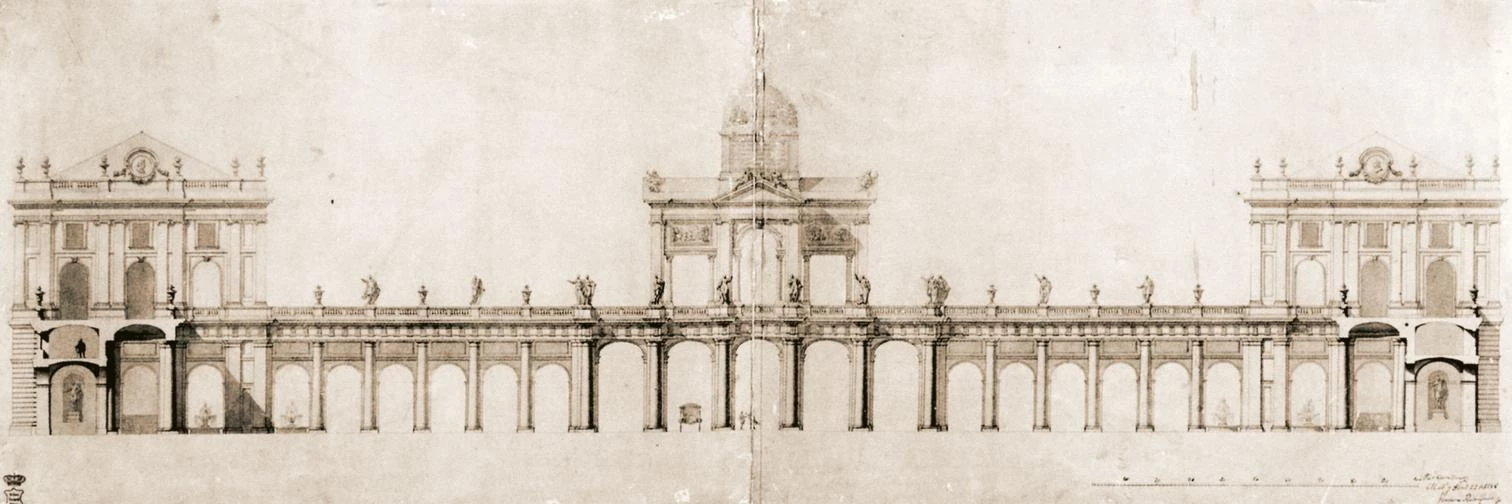

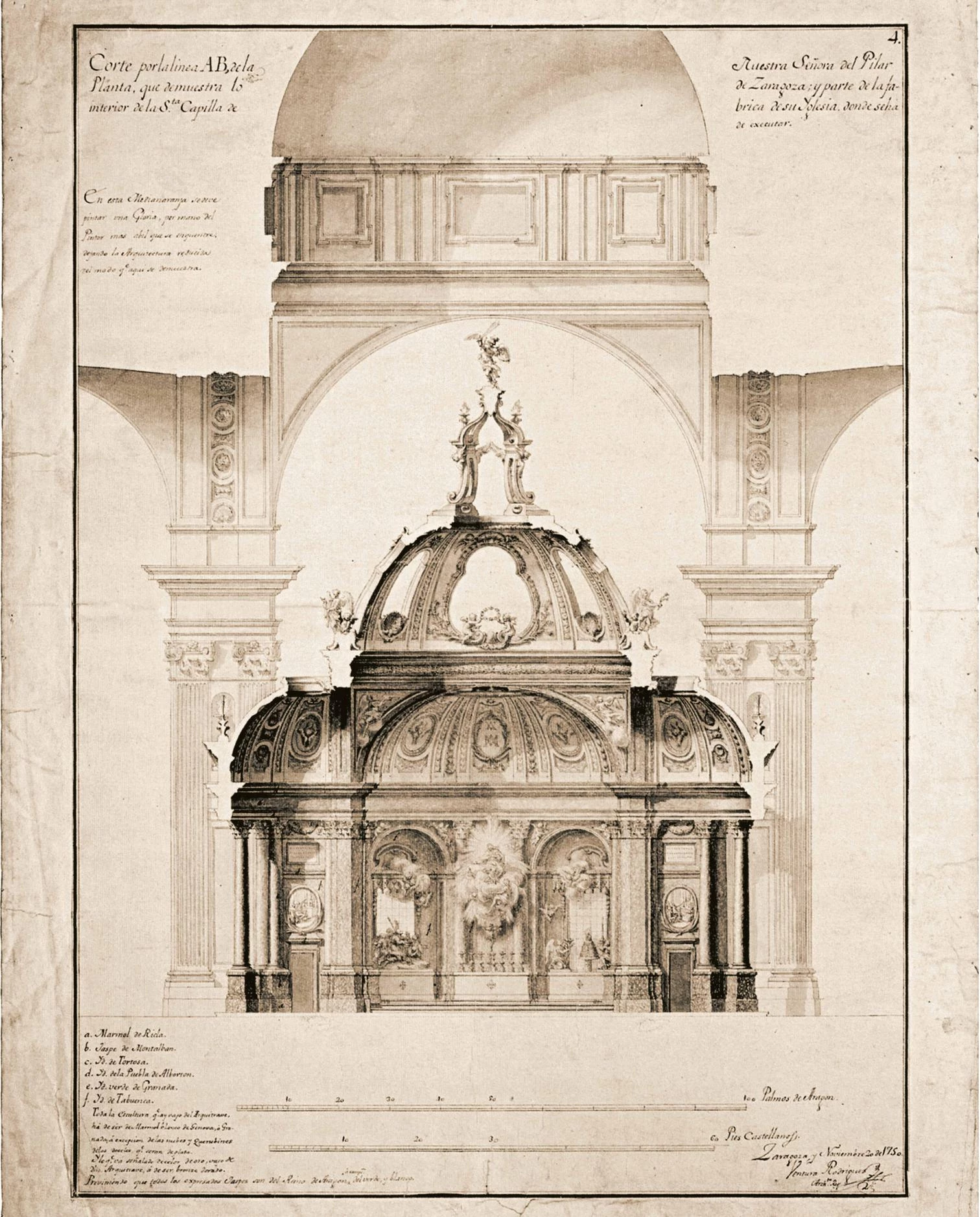

From his earliest experiences as draftsman at the Royal Palace of Aranjuez (1727-1735) – at the service of engineers, architects, and decorators from France and Italy, such as Marchand, Galluzzi, and Bonavia – to the years with the Torinese architects Juvarra and Sacchetti at the Royal Palace of Madrid, Ventura Rodríguez drew the attention of superiors by virtue of his drawing talent. It was this skill that brought him out of the shadows of the ateliers of the Sitios Reales, and his career began to thrive under the Hispanophile patronship of Fernando VI. Ventura Rodríguez played an important part in the creation of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, of which he was named the first director of architecture, and he took on his first major commissions in court, initially of Baroque lineage, such as the Church of San Marcos. By the mid-1750s Rodríguez had begun to mold his Piedmontese language, inspired in Juvarra and Sacchetti, with classicist reflections and Herrerian references. But this rising career totally collapsed in 1759 with the arrival of Carlos III from Naples, when he was dismissed from royal service and he had to seek new clients and prospects.

This was the point at which Ventura Rodríguez set out to carve a new career. Proclaiming Rodríguez a restaurador of national architecture was an acknowledgment not only of his affinities with Herrera, but also of the extent of the impact that his works – carried out throughout Spain and catalogued in typological lists provided to us by his nephew Manuel Martín Rodríguez, also an architect – had on a national scale. The breadth of Rodríguez’s activities is not only attributable to a generalized broadening of opportunities that the profession was then enjoying in Spain. Most architects of his generation settled for the comfort of working in a limited but secure and familiar context: Francisco Sabatini in works commissioned by the King, Diego de Villanueva and José de Castañeda in the Academy, José de Hermosilla in the Corps of Military Engineers. But Rodríguez, after successfully overcoming the trauma of Carlos III’s dismissing him from royal works, took a different path to stay active, a path based on exploring new sources of patronship in the kingdom’s most powerful judiciary and administrative institutions, among them Madrid’s Ayuntamiento and the Council and Chamber of Castile. He thus became one of the ‘versatile men’ that Kubler described in The Shape of Time: flexible, capable of maneuvering and negotiating at moments of great changes and turbulences.

What was it in Rodríguez’s character that enabled him to stretch the scope of his activities and network of patrons? How did this mozo de particular habilidad from a modest family of journeymen rise to positions of such enormous responsibility and earn the respect of such a broad spectrum of Spanish society – courtiers in charge of the Sitios Reales, consiliarios of the Academy, the brother of the King, grandees, cardinals and bishops, ministers of state, Madrid Ayuntamiento aldermen, and advisors and attorneys of the Council and Chamber of Castile.

It was not conferred by inheritance, elite education, or a pension to study in Rome or Paris, but earned in years of professional dedication and the cultivation of a set of social skills admired by many, whether Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, the Infante Don Luis de Borbón, the Marquis of San Leonardo, the Count of Altamira, the Duke of Alba, or Cardinal Lorenzana.

The Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando played a key role in the transformations that architecture was undergoing at the time, first by promoting the status of the architect as a learned professional, and, second, by providing him with a stimulating group of colleagues actively engaged in the discussion of new and often contested ideas. The tropes of conflict and factionalism, however, have often turned our eyes away from the learning and new perspectives developed in this new arena. Of course, there was competition and deeply held points of view. Criticism, especially of the manuscripts submitted for publication in the name of the Academy, was harsh. And among these members there were turbid, bitter personalities like Diego de Villanueva, whose provocations and complaints have perhaps received more attention than they deserve.

Rodríguez too had moments of turmoil in his life, but he took them in stride and overcame them. Without a doubt his sense of measure, his urbanity, his affability helped him shift course, keep going, and leave to posterity a vast built oeuvre, armed as he was with a capacity to navigate the changing sea that Madrid’s artistic climate was at the time. He had a knack for finding new commissions, private and institutional alike, and addressing the many different specifications that came with them, this through a knack for modifying the ‘character’ of his designs to make them better satisfy the functional, economic, and expressive requirements of the clients, a critical asset in such situations. The career of Ventura Rodríguez reminds us that the architect’s job is not just to design, but also to serve society.

An extract from a lecture at Madrid’s Royal Academy coinciding with the Ventura Rodríguez exhibition organized to celebrate his third centenary.