Fog in the Desert

Ameeting in Kuwait introduces a balance of the year which, besides events and disasters, reflects on the superficial character of the latest architecture.

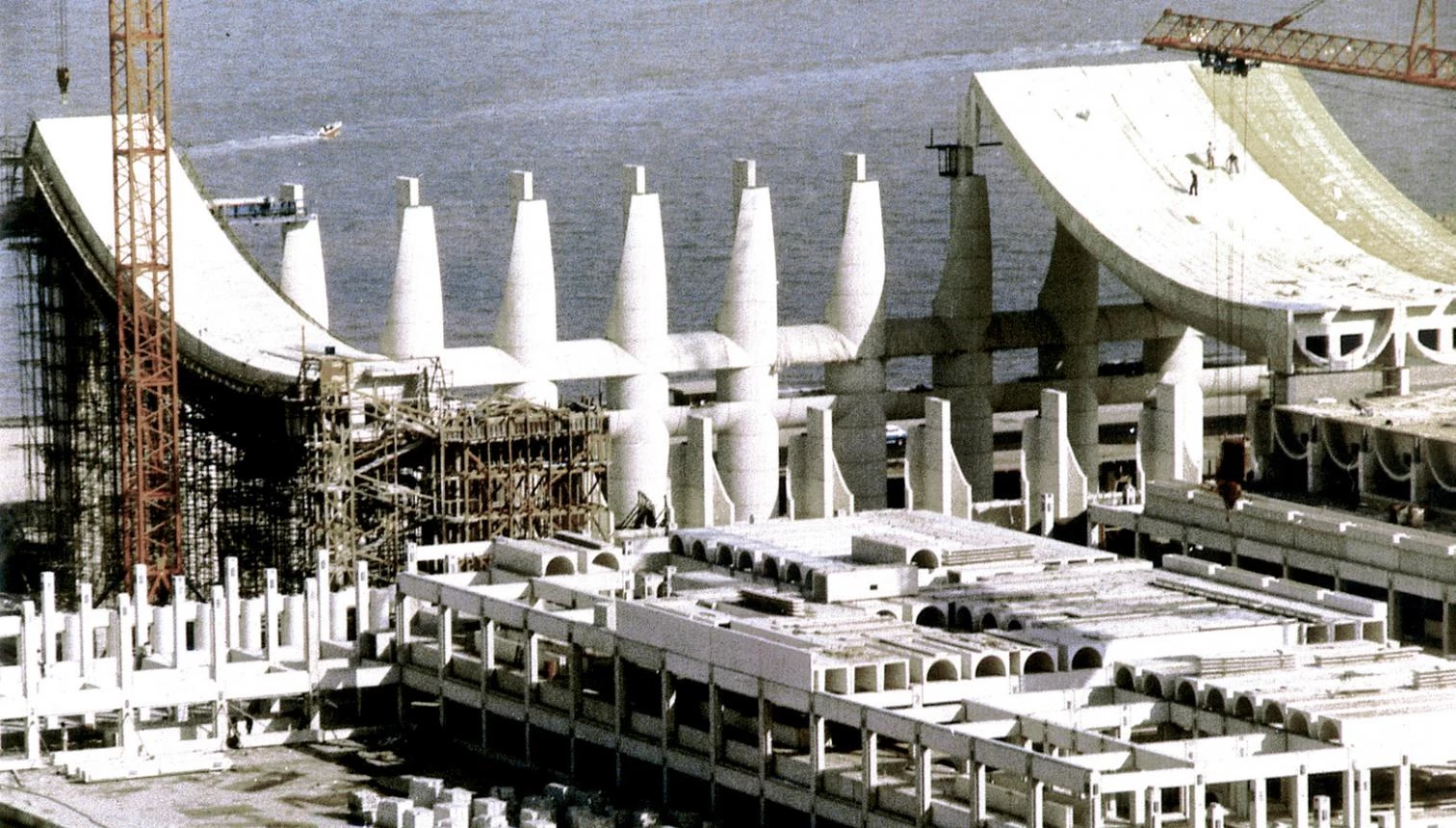

We do not expect fog in the desert. Nevertheless, we western critics and our counterparts of the Muslim world who have been summoned together in Kuwait by the Aga Khan Foundation are met by a mist that is denser than the mythical British split-pea soup, a phenomenon so unusual as to make the front page of the Arab Times, an English-language daily of the emirate, blurring the silhouette of the city’s architectural icon, the Kuwait Towers, a construction of water tanks that serves as well as a lookout and a restaurant. While dining in one of the towers with Paula Al Sabah, married to a son of the emir, a woman exquisitely educated in the United States like all other members of the tribal elite that runs the country, it occurs to me that the cloud inside which we are conversing is a perfect metaphor for the cottony blindness of the world’s privileged. As we savor desserts flown in that same morning from a Parisian patisserie, we are floating many meters above the dunes that hide the lake of petroleum on whose viscous darkness rests the prosperity of the Gulf, but also ours.

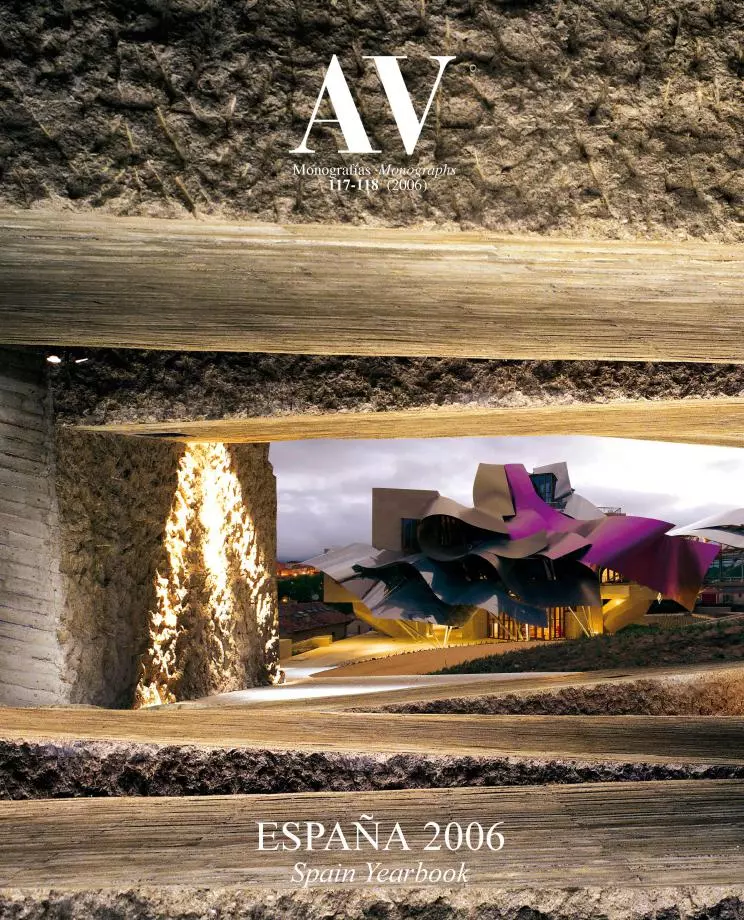

The parliament of Kuwait, a work by Utzon damaged by the invasion of Iraq, during its construction.

The Kuwaitis follow Saddam Hussein’s trial with indifference. Gone, almost entirely, are the marks of the invasion that in 1990 provoked the first Gulf War – with unforeseen architectural consequences in Spain, such as the provisional paralysis in Madrid of the twin towers of the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO), after the group’s plundering by Javier de la Rosa and Fahad Al Sabah, or the celebration of victory over Iraq through the lyrical Kuwaiti Pavilion at Expo ’92 in Seville, which Santiago Calatrava designed as an arch of triumph of moving palm trees –, and one hardly remembers that the geopolitical balance of the planet still rests on this fragile hinge where energy reserves cross with the clash of civilizations. These pre-Christmas weeks, passenger planes fly fearlessly over a shaken, pre-electoral Iraq, and in Kuwait people worry more about traffic jams in the highways than about metal detector arches at the entrances to hotels or the routinary checking of undersides and trunks of vehicles. The parliament building designed by Utzon, with its huge canvases of concrete hanging from the sculptural portico, has been entirely restored from the damages it suffered during the occupation, and continues to be the country’s most beautiful building, while new skyscrapers built in more corporate styles are sprouting left and right, alongside shopping centers with Californian airs and incomparable luxuries. If we go by the real estate fair that accompanies an ongoing congress of local engineers, we cannot help thinking that Kuwait is preparing to be a second Dubai – the Gulf emirate currently second only to Shanghai in number of cranes.

The Kuwait Towers (several water tanks that also serve as lookout and restaurant, built in the seventies by a Swedish firm and that have become the symbol of the emirate), during a rather unusual day of fog in the Gulf.

Contemplated from this Persian or Arabian Gulf on whose fortune our own so much depends, the year’s architectural events fade in the blue fog of distance and in the indifference of chance. The cities of the year were Aichi, site of a International Exposition focused on sustainability that accommodated a much praised Spanish Pavilion, a ceramic and chromatic work of Alejandro Zaera and Farshid Moussavi; Istanbul, venue of a congress of the International Union of Architects that awarded its triennial medal to the Japanese Tadao Ando; and London, elected host of the Olympic Games of 2012, beating Paris, Madrid, New York, and Moscow, the day before being the target of a chain of terrorist attacks. But for a year that began under the tragic effects of a tsunami that claimed a quarter of a million victims, perhaps the list of cities ought to include New Orleans, dramatically devastated by the hurricane Katrina; Paris, scene of the decade’s worst urban riots; Barcelona, where the sinking of the Carmelo quarter brought to light the issue of urbanistic corruption; and Madrid, which saw the Windsor office tower burning and realized how vulnerable the vertical city is: a roster of disasters that may soon include Tokyo, a privileged hub of fashion architectures, but today also the epicenter of a political and technical scandal that threatens to cut short Japan’s economic recovery, after revelations of the architect Hidetsugu Aneha’s falsification of seismic calculations in over fifty buildings, which will now have to be demolished, bringing up a problem that experts say could affect tens of thousands of constructions in the country, thanks to detection of the systematic cost-reducing complicity of architects, builders, and even inspectors, often private companies since the sector was liberalized.

Natural disasters marked a year which began mourning the victims of the tsunami of the Indian Ocean and had its worst episode in the destruction of New Orleans by hurricane Katrina

Incidentally, this was one of the issues addressed at the Kuwait gathering, and this because it affects that essential factor of security and life without which it is obscene to be lavish in aesthetic musings, which are perhaps reasonably limited to the lazaret of newspapers’ culture supplements, which cannot compete with the juicy polemics of the local news section, the exotic proposals of the travel pages, or the sophisticated lifestyle coverage of the Sunday magazines, not to mention the endless advertising of the real estate sections. After all, it is reasonable to think that the urbanistic mutations of one’s own city, the architectural glamor of tourist destinations, or domestic decoration – not to mention the buying of a dwelling, a rite of passage that marks one’s stepping from the freedom of youth to the mortgaged chains of maturity – are all eons more interesting than the often lewd ramblings about the physical body of architecture and its fleeting shadows, an activity of idlers like the critics gathered in the unexpected mists of the Gulf.

To discipline this tameless tribe, and in the spirit of guiding the reader, let me attempt to finish a short adaptation of a transatlantic doctrine in matters of obscenity, one I extract from the instructions offered by a Virginia-based organization called Parents Against Bad Books in Schools, authors of a list of works judged “inappropriate, obscene, or vulgar,” including the likes of Umberto Eco, Margaret Atwood and Gabriel García Márquez. According to The Times Literary Supplement, the ‘badness’ of texts is measured with a scale of four registers having to do with sexual content, from B (Basic) to G (Graphic), on to VG (Very Graphic) and EG (Extremely Graphic). Examples are given: B (large breasts); G (large, voluptuous bouncing breasts); VG (large, voluptuous bouncing breasts with hard nipples); EG (large, voluptuous bouncing breasts with hard nipples covered with glistening sweat and bite marks). An equivalent architectural scale to prevent critical pornography could go as follows: B (large volumes); G (large, undulating and agitated volumes); VG (large, undulating and agitated volumes clad with titanium): EG (large, undulating and agitated volumes clad with titanium, with a moist gloss and trembling texture). Such a scale could serve as a guide for architectural critics lost in a fog of self-absorbed sensuality while the dark pulse of the world beats beneath the sand.