Form Follows Tracks

El estadio en Baracaldo de Arroyo y la estación en Basilea de Cruz y Ortiz ilustran la capacidad de la forma para dar identidad a paisajes anónimos.

A syncopated frieze and a topographic profile, is how one might sum up the new works in Baracaldo and Basel. The football stadium built by Eduardo Arroyo on the left bank of the Nervión estuary traces its at once regular and turbulent geometry with the light tape of a folded canopy, while the volume erected by Antonio Cruz and Antonio Ortiz on the platforms of the Basel railway station defines its urban image with the broken silhouette of a metal roof. Each building seems to be able to apocopate in a line that abbreviates its shape, which is stressed on both facades by the pedagogical thickness of the section, and such a stenographic synthesis simultaneously serves as a logo for the place and a signature of the author: an emblem of the work in the abrasive anomy of urban peripheries segmented by train tracks or waste lands, and a calligraphy of the architect who alleviates the anonymity of discontinuous urbanity with the singular gesture of an individual flourish transformed into a collective sign.

The zigzagging lines that characterize the projects – the frieze of Baracaldo soccer stadium and the jigsaw of the remodeled Basel railway station – are at once logos of the buildings and signatures of their authors.

The straight and translucent meander of Baracaldo exteriorly expresses the arrhythmic modularity of a grandstand that is interrupted here and there so that tiers alternate with tongues of grass, in the process impressing upon us a memorable image of the stadium. But it is also a compositional tactic characteristic of Arroyo, one he used, for instance, in the work that first brought him fame, the kindergarten of Sondica. On its part, the fractured line of Basel adapts to the various demands of the existing canopies and new commercial uses, creating a serrated profile that is at once an echo of the mountainous horizon and a cutout figure that gives the building an identity in the panorama of the city. But the broken line is likewise a term in the formal vocabulary of Cruz & Ortiz, one they used in works like the Spanish pavilion in Hannover 2000 or the visitors’ center of Doñana. The edge of Bara caldo and the saw of Basel reconcile program and language with a syncretic stroke that, over the stubborn life of forms, testifies to the fertility of the form in negotiating the conflict between function and image, through a sudden emulsion that amalgamates the material circumstances of the project with the expressive intentions of its author.

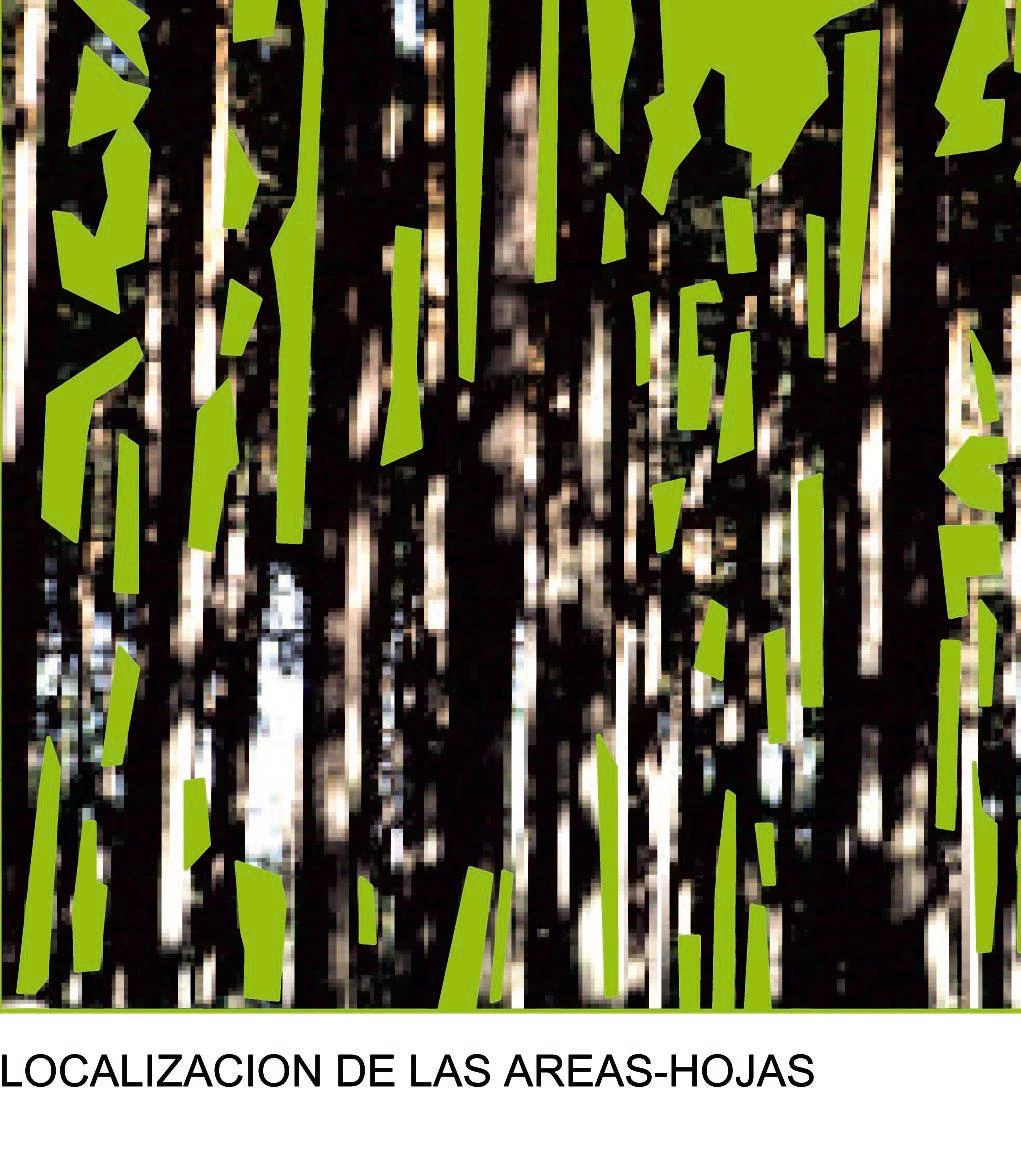

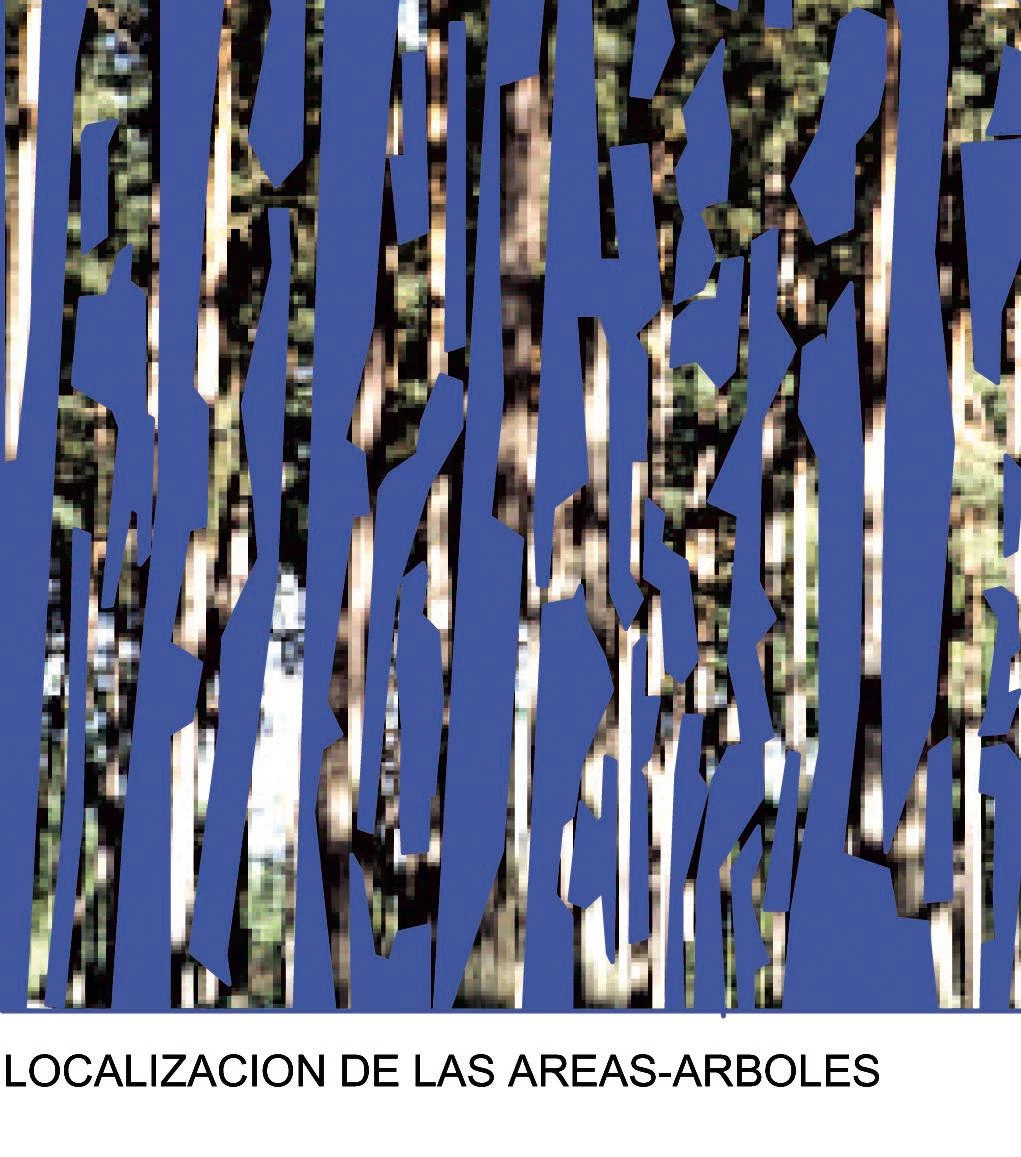

The steel latticework of Baracaldo stadium, through which one can see the multicolor stands, takes inspiration from a forest of slender trees filtering light through foliage, as shown in the sequence of images.

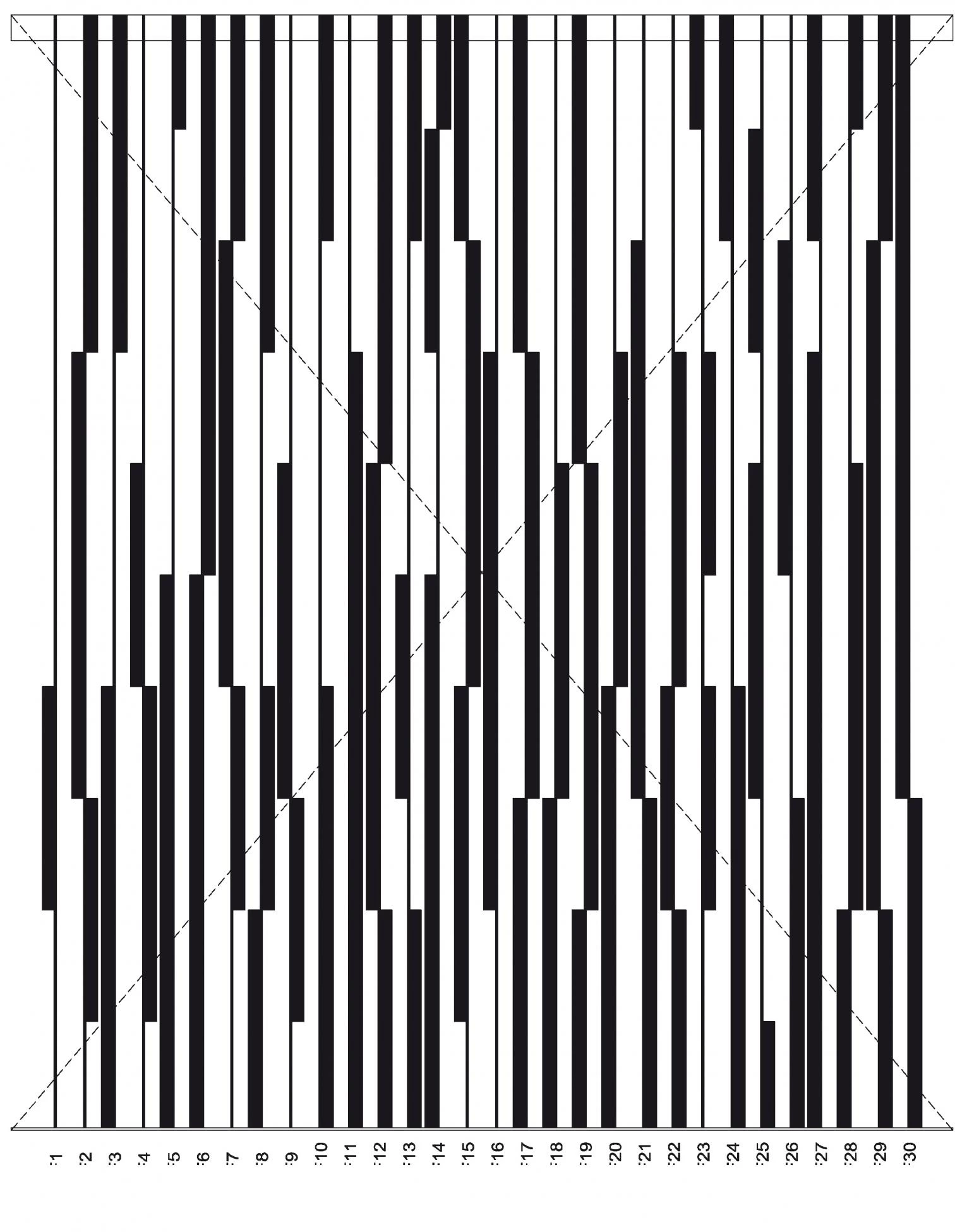

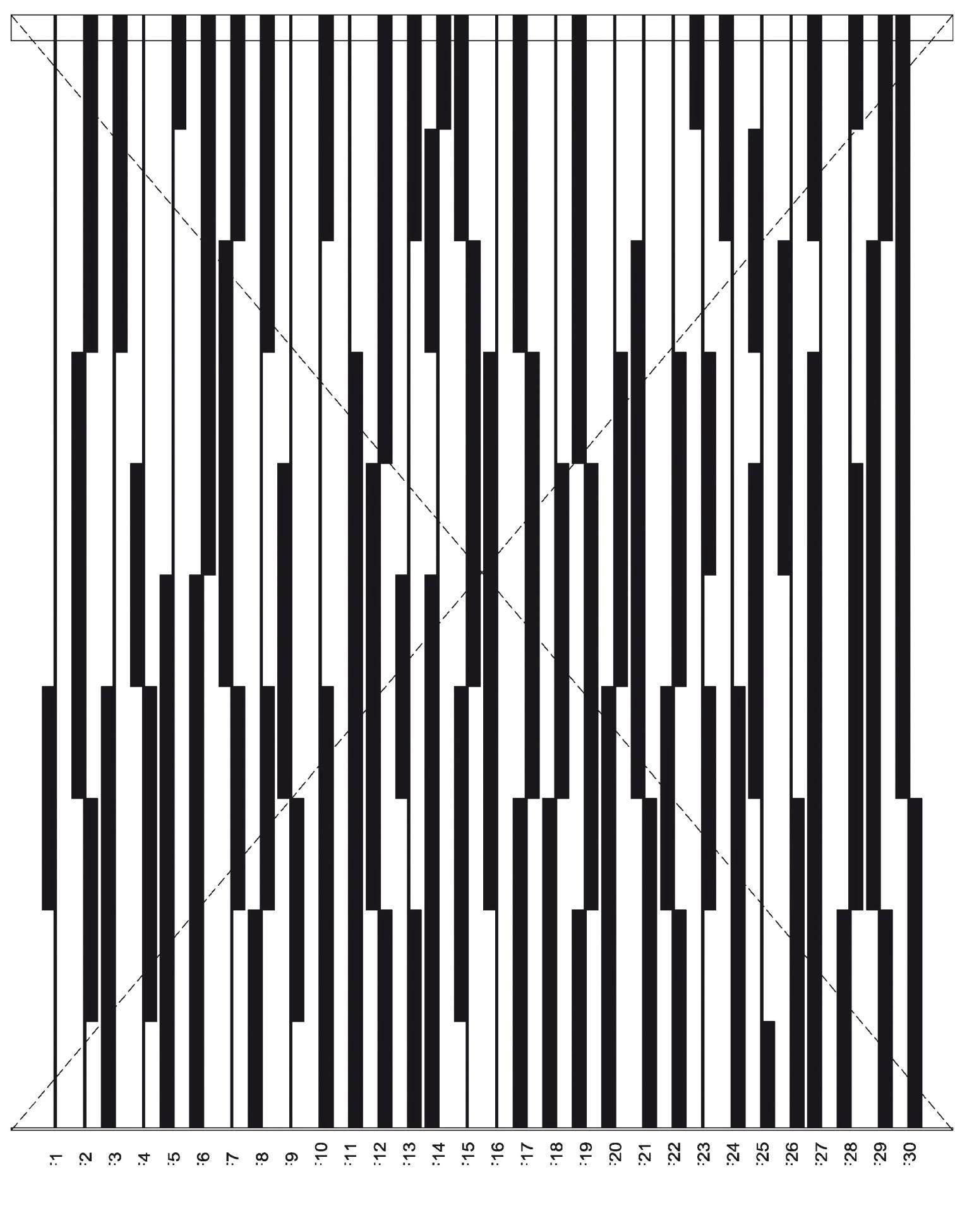

In Baracaldo, Arroyo’s stadium rises on the old site of the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya, installations torn down in the process of reorganizing the country’s iron and steel industry, making it possible for some fifty hectares of land along the estuary to be urbanized for residential and recreational uses. On terrain degraded by continuous industrial use (which made foundations as deep as 40 meters necessary), in an environment with no other references than factory traces, the young Bilbao architect has completed an artefact of steel lattices and polycarbonate marquises that is light by day and spectral at night, and seems to float between the tracks and cranes of a urban periphery. And behind its lightweight perimeter, crowned by four illumination towers that all the more stress its diagrammatic immateriality, hides the rare spectacle of a sport field rectangle flanked by grandstands with arbitrarily discontinuous, multi-colored seats.

As he did in the same town’s Plaza de Desierto, Arroyo combines modular regularity with aleatory uncertainty, and the result is a football field whose grass stretches on randomly to the perimeter, interrupting the tiers with fortuitous picturesqueness and outlining the upper canopy with identical accidentality. In larger stadiums (the seating capacity of this one does not reach the 8,000 mark), such fragmentation of spectators has occasionally been attempted as a way of controlling crowds. A case in point is Bari, where Renzo Piano divided the tifosi in concrete ‘petals’. In Baracaldo, however, the fragmentation comes from the architect’s lyrical and musical language, reinforced here by his lack of empathy with what Arroyo calls football’s ‘masculine catharsis’, and with that footballing communion of spirit that in this stadium will not find expression in the ‘wave’. A post-footballing stadium, one that the author pictures being used in the course of the week by Basque txistulari pipers, pro-amnesty movements, and ‘funny and perverse’ housewives, Arroyo’s work is so inventive, poetic, and refined that we just have to pardon his subterranean indifference to the sport that the English brought to the fields of Biscay.

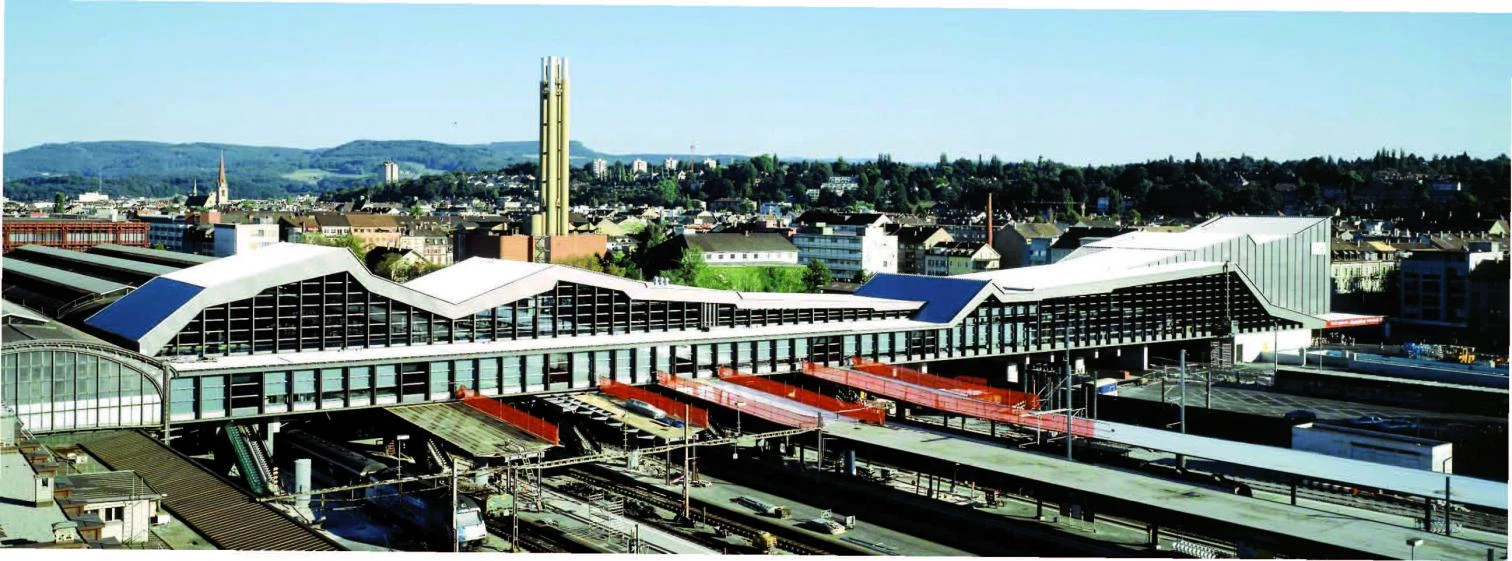

In Basel, Cruz & Ortiz have completed their renovation of the railway station, following a project that won a competition in 1996 and which they have developed in conjunction with the Lugano architects Giraudi and Wettstein. As they did, though differently, in their celebrated Sevillian station of Santa Justa, they have transformed what was a pass-through station, with its hall on the edge of the tracks, into a complex with the physical and symbolic dimension of a terminal station, and this they did by replacing the underpass leading to the platforms with a large gangway, decked with stores, that links up the city zones separated by the tracks, in the process giving the building the representational profile required of a urban gate.

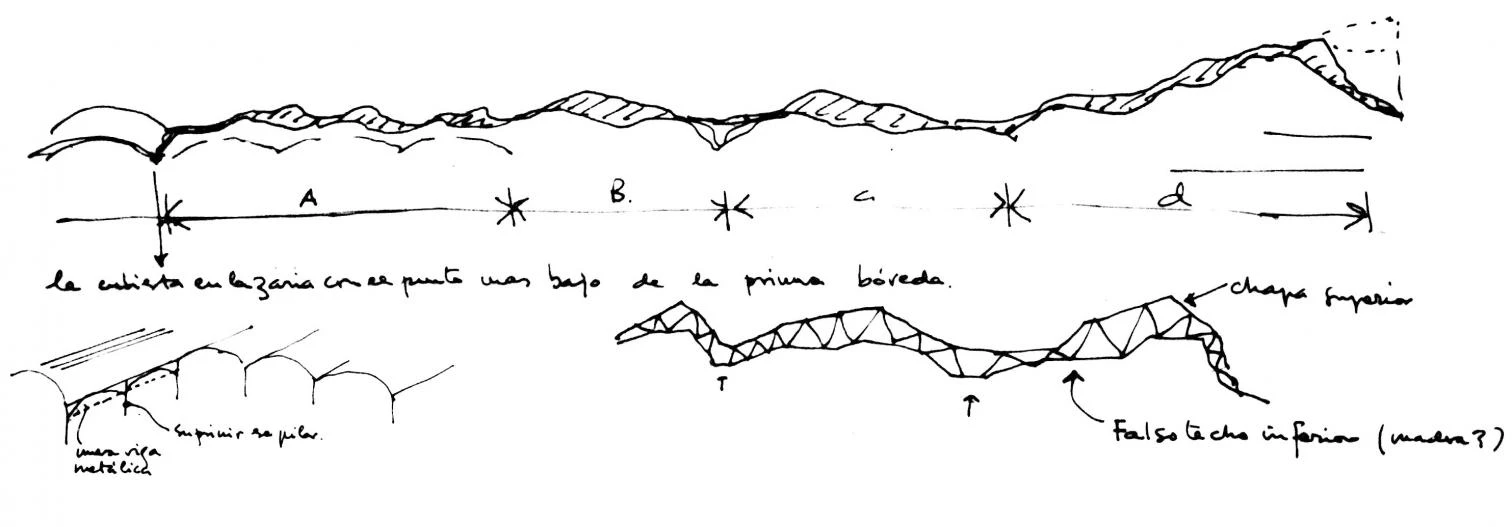

The sawtoothed roof of the new Basel railway station gives singularity both to the faraway profile of the building and to the interior space of the large footbridge with shops that stretches over the tracks.

Its varying height addressing different functional requirements, the colossal serrated roof nevertheless has the synthetic spontaneity of its preliminary conceptual sketch, and its nervous outline crystallizes the pulse of its authors on the territory. At once industrial and eventful, its silhouette has the sober elegance of what seems effortlessly made, and the Sevillian architects have mustered all their professional and artistic mastery to orchestrate the building’s uses beneath an unmistakable gesture: a formal mood not unlike what they showed in Madrid when they summed up a track-and-field stadium in the frozen wave of a titanic concrete grandstand that was immediately baptized as ‘La Peineta’ (now being enlarged by its makers to adapt to the Olympic demands of a city aspiring to host the 2012 Games), or in the projects that are marking their growing international presence, from the housing developments of Maastricht and Lisbon to the shopping center at the foot of the Swiss Alps or the extension of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum.

From Baracaldo to Basel, the vitality of the form as an architectural tool smilingly evokes times when the term ‘formalist’ was offensively pejorative, and silently recalls the obstinate validity of Le Corbusier – who has nourished Cruz & Ortiz through Oíza and Moneo in the same way that it has influenced Arroyo along an itinerary that included a stopover with Koolhaas. Nevertheless, we cannot ascertain that this tenacious school is the sole referential pole on the Iberian Peninsula, and it is a sign of Antonio Ortiz’s even-tempered eclecticism that the Biennial of Spanish Architecture overseen by him should, along with Alejandro Zaera’s sea terminal of Yokohama – another product of OMA-filtered Corbusian formalism – highlight a work as rigorous and invisible as Víctor López Cotelo’s housing development in the historic quarter of Santiago de Compostela: a project as Zen as the Galician politician Rajoy’s electoral campaign, in the wake of the laconic master that the likewise Galician Alejandro de la Sota was, and in whose minimal and exact landscape one breathes the same beinahe nichts of the master of Aachen, who was not Galician but perhaps deserved to be.