The Multitude in Motion

Multiple multitudes took the stage during a convulsive year: hopeful multitudes, with the huge Women’s Day demonstrations in March, in the wake of the #MeToo movement and the Gay Pride parades; identitarian multitudes of national exaltation, which succeeded in putting strongmen in the governments of Italy, Mexico, and Brazil – like those already installed in the United States, China, Russia, Turkey, or Hungary –, protested in Catalonia the trial of secessionist leaders and made themselves visible in Spain as a consequence of the regional elections in Andalusia; angry multitudes contesting the rupture of the social pact by the crisis, which rose up in November with the French yellow vests; and des-perate multitudes in exoduses triggered by war or misery, which created migratory crises at the borders of the countries of North America or Southern Europe, and which in summer had their epicenter in the Spanish coasts.

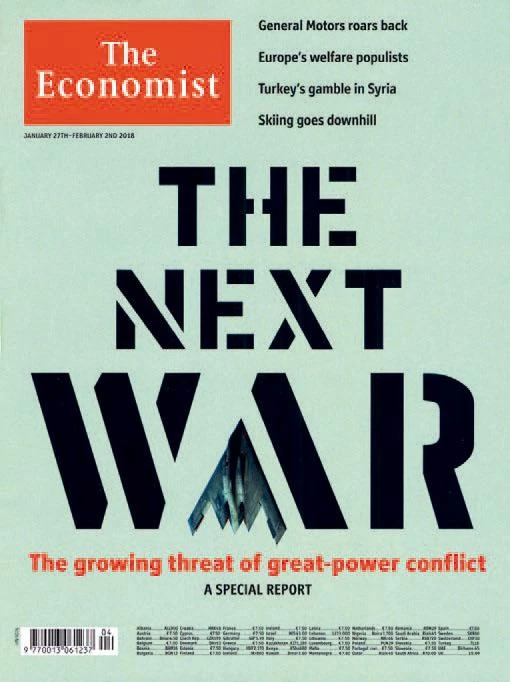

All this while the world trusted it could avoid Thucydides’s Trap, which would predict military confrontation between the American superpower in decline and the Asian one on the rise, a conflict that the US and China rehearsed through feints of commercial war, the quarrel over digital leadership, and threats of cybernetic intervention; while Europe was fractured by Brexit and the Visegrád Group, deplored the weakening of the Atlantic link, and helplessly watched China’s economic and financial penetration through infrastructures along the New Silk Road; and while climate change became more acute, with extreme expressions like the devastating fires of California, Greece, or Australia.

In Spain, the so-called Catalan Process, which the year before had led to an illegal and ephemeral unilateral declaration of independence, now saw its leaders prosecuted, some having fled the country, while in June a motion of no confidence supported by se-cessionist parties made the socialist Pedro Sánchez Prime Minister, initiating a period of increasing political tension and polarization barely alleviated by sport victories and good results in an economy that is growing vigorously and creating jobs, but falls short of reducing social inequalities. Although the ‘new optimists’ – from Steven Pinker to Hans Rosling – encourage us to look at trends in the long run, our perhaps myopic perception of the short-term invites little enthusiasm.

‘Yellow vests’ and women marched in Paris or in Madrid, migrants crossed the Mediterranean, and magazine covers warned against the risks of war or the dangers of journalism, honoring those who suffered persecution.

If economic health is filling Spanish cities with cranes, few of them are connected to public projects. What we are witnessing instead is a proliferation of private initiatives involving the construction or renovation of high-end apartments, offices, or retail spaces. Architecture of quality survives in small commissions of cultivated clients or in modest works of different administrations, with a varied regional register extending from the intelligent and numerous endeavors in Catalonia to the persistent paralysis of Madrid. Two such small-scale projects are the fine stone houses built by Emilio Tuñón in Cáceres and Harquitectes in Girona, eloquent proofs that aesthetic, intellectual, and technical ambition can be expressed with the limited dimensions of a one-family residence.

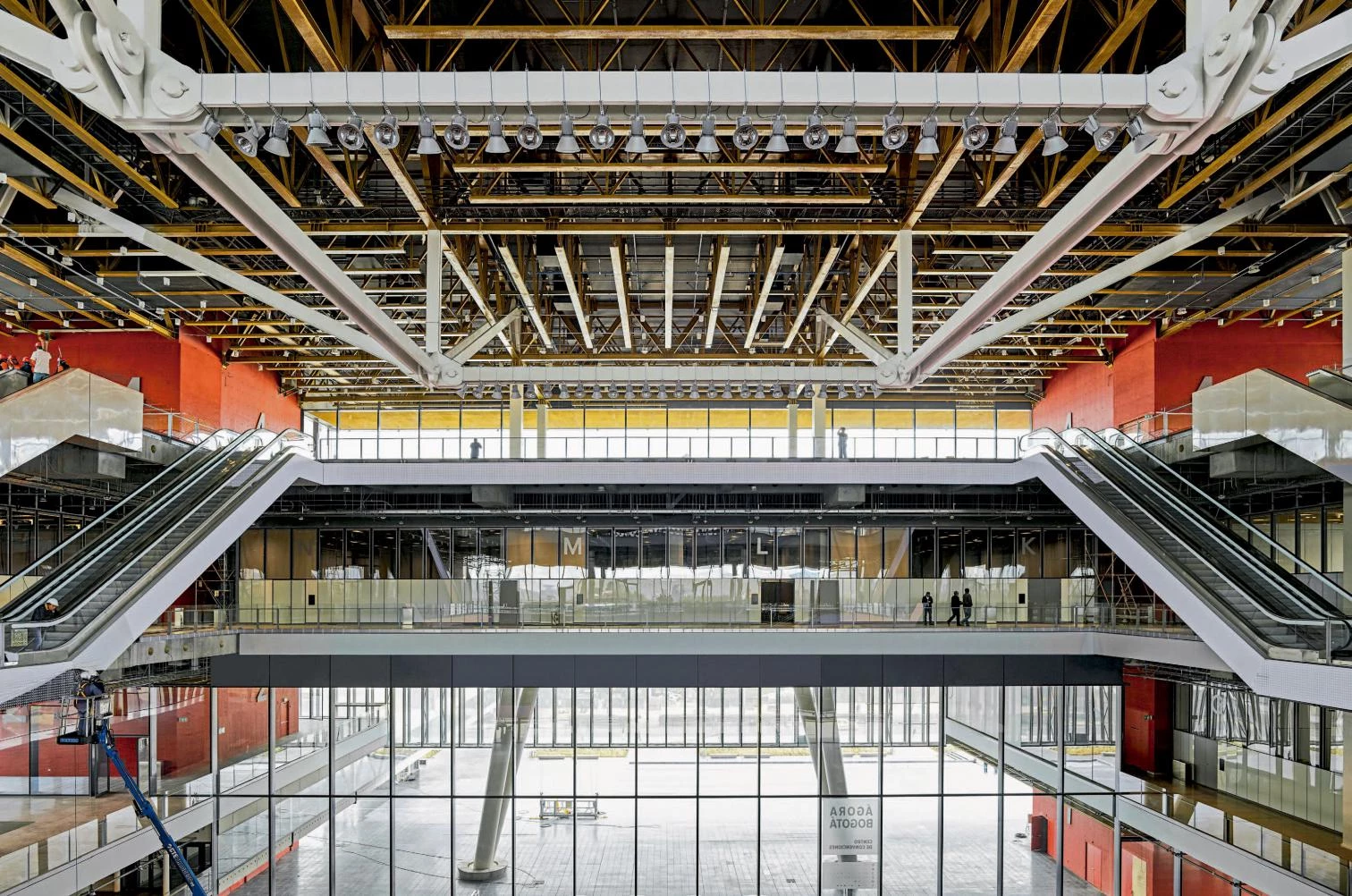

Harquitectes or Tuñón completed stone houses, Perrault finished León’s Ferial, and outside Spain, Nieto Sobejano opened the Arvo Pärt Centre in Estonia, and Herreros with Bermúdez Bogotá’s convention center.

With exceptions like Dominique Per-rault’s titanic exhibition center in León, most of the major Spanish projects were located outside Spain: the elegant Historical Archive by Ignacio Mendaro in Oaxaca; the colossal Convention Center by Herreros and Bermúdez in Bogotá; and the exquisite Arvo Pärt Center by Nieto Sobejano in Estonia, which honors the great composer amid pine trees on the Baltic coast. To these three we must add the University of Silesia’s Faculty of Radio and Television in the Polish city of Katowice, by BAAS Arquitectura; the new parliament of the Canton of Vaud by Bonell & Gil; the school in Orsonnens, also in Switzerland, by Ted’A arquitectes; and the media library in Ghent by RCR.

The year’s major international milestone was the long-awaited inauguration of the Qatar National Library, an iconic project of Rem Koolhaas that counts among the numer-ous cultural works attesting to the ambition of the small country of the Gulf, now subjected to economic and diplomatic blockads by its powerful neighbor, Saudi Arabia. But we must also mention European works like the refined Palace of Justice skyscraper in Paris by Renzo Piano, the sculptural Victoria & Albert Museum in Dundee by Kengo Kuma, or the monumental James Simon Galerie in Berlin by David Chipperfield, which culminates his redevelopment of Museumsinsel; American ones like the compact university building by Barclay & Crousse in Peru – which, incidentally, won the American Mies Award – or the headquarters of Silicon Valley technology firms designed by Norman Foster or Frank Gehry; and Asian projects like the pixeled tower in Bangkok by Ole Scheeren or the lyrical art pavilion and chapel in South Korea by Álvaro Siza. And definitely the most visited constructions were the chapels commissioned by the Vatican in the context of the Venice Architecture Biennale, which spanned a whole spectrum of design, from the stony magic of the one built by Eduardo Souto de Moura to the lightness of the tensegrities executed by Norman Foster.

If the Biennale was the most significant event, the centenaries of Jørn Utzon, Aldo van Eyck, Paul Rudolph, or Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza gave rise to various publications and exhibitions, which joined those on Tadao Ando at the Centre Pompidou, Piano at the Royal Academy, Victor Papanek at Vitra, or Francis Kéré at Museo ICO, the latter with a public success that speaks in favor of essential architectures seeking usefulness and beauty with limited means. Important, too, was the Fundación Arquitectura y Sociedad’s congress held in Pamplona around the theme of the city (a theme likewise explored by the Norman Foster Foundation), which was inaugurated by King Felipe VI with the participation of the writers Eduardo Mendoza and Leonardo Padura, the mayors Joan Clos and Manuela Carmena, and the revered urban planners Jan Gehl and Jaime Lerner.

Every year has its share of catastrophes, and apart from the many that have caused suffering and human losses in many parts of the planet, two debacles of different nature were of particular interest to architects and engineers: the collapse of the Morandi Bridge in Genoa killed over forty people and raised questions about structural decisions, maintenance policies, and private management of infrastructures, matters of great importance which Piano’s proposal for a new bridge partly tries to address; and the cancellation, following a minority public vote, of the already partly built new Mexico City International Airport, designed by Foster with an innovative spatial structure, was a warning against the risks of participatory demagogy, which skirts political responsibility in major infrastructural decisions.

In the awards section, the Pritzker went to the veteran Indian master Balkrishna Doshi, the Imperiale fell upon the French Christian de Portzamparc, and the Venetian Golden Lion honored the career of the British critic and historian Kenneth Frampton, while Spain’s National Architecture Prize acknowledged the rigorous and discreet trajectory of Manuel Gallego, and the Swiss Award commended the achievements of the young architect Elisa Valero

Siza and Castanheira opened an art pavilion in South Korea, Souto de Moura and Foster built chapels in Venice, and Barclay & Crousse received the American Mies for their university building in Peru.

The decease that left the largest void was perhaps that of Robert Venturi, but we also mourned Neave Brown and Will Alsop, Paul Andreu and Paul Virilio, Gillo Dorfles and Tomás Maldonado; and amongst us we will miss the architects Antoni Ubach and Antonio González Cordón, the urbanist and sociologist Mario Gaviria, and the journalist, painter, and poet Vicente Verdú, who did so much for architecture from the pages of the newspaper El País or those of this journal. The American magazine Time decided this once to multiply its Person of the Year fourfold, choosing journalists who were persecuted trying to tell us what is happening in a world corrupted by fake news and the manipulation of minds. Multitudes on the march celebrate, demand, or suffer, and individuals ought to follow suit, divided as we are between the historical optimism offered by data and the daily despair caused by events.