The Intimacy of Roundness

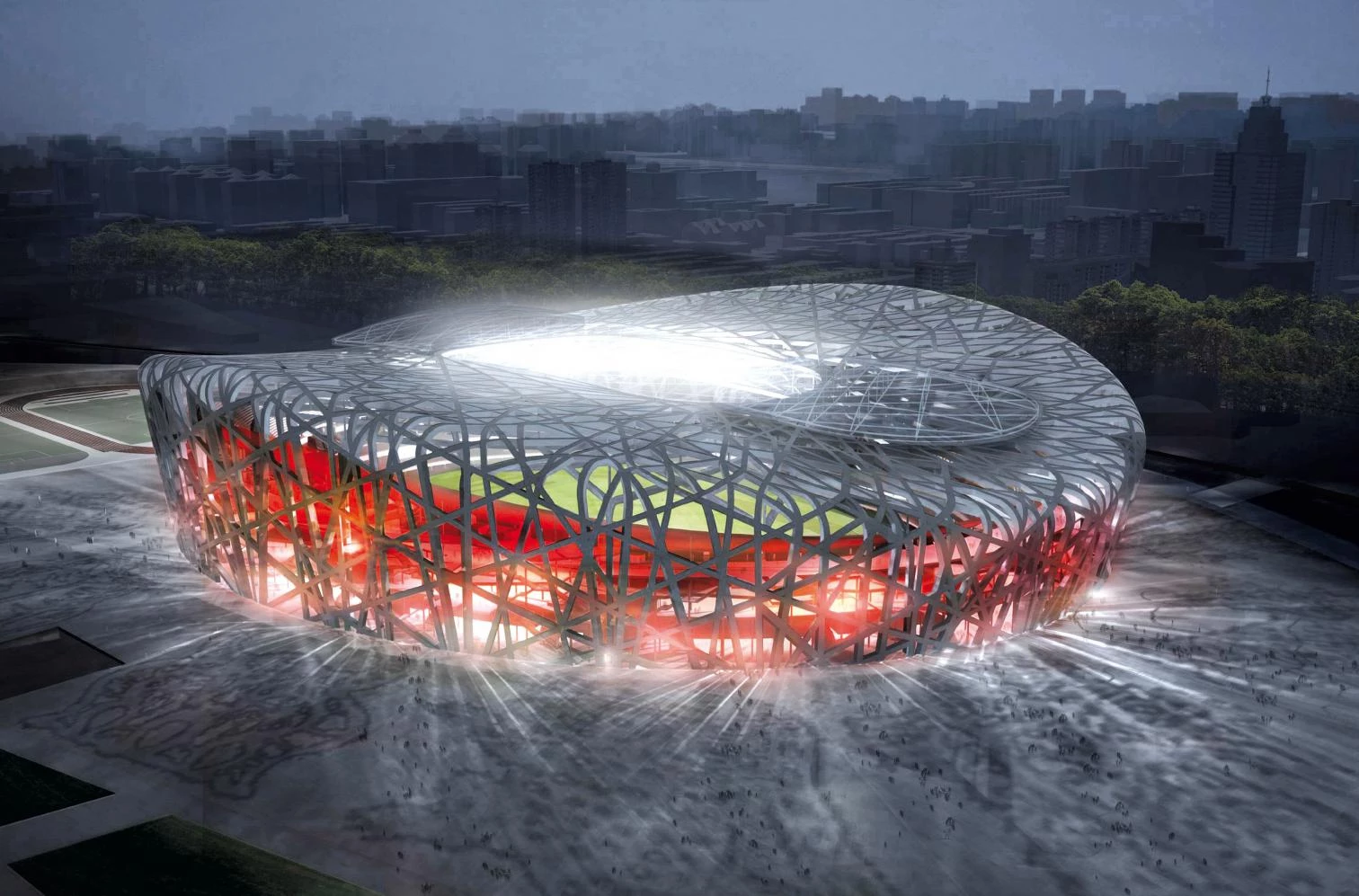

H & de M shall build the olympic stadium of Beijing as a pneumatic nest, in keeping with previous sports constructions in Basel and Munich.

Peter sloterdijk begins his trilogy Spheres by quoting Gaston Bachelard: “The difficulty we had to overcome... consisted of staying clear of any geometric evidence. In other words, we had to take off from a kind of intimacy of roundness.” And the German philosopher relies on the author of The Poetics of Space to lament the human being’s loss of “its age-old shelter in the bubbles of illusion inter-woven by himself,” given that, if “to inhabit already always means to form spheres... then human beings are those that build round worlds.” With their trilogy of stadiums, the Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron have built round worlds, striking an amazing dialogue with the German phenomenologist, whose spherology, understood as an exploration of “organizations of archaic intimacy” or as the “design of the space of primitive people”,enters in resonance with precincts described by their authors as “simple and almost archaically direct in their spatial impact.”

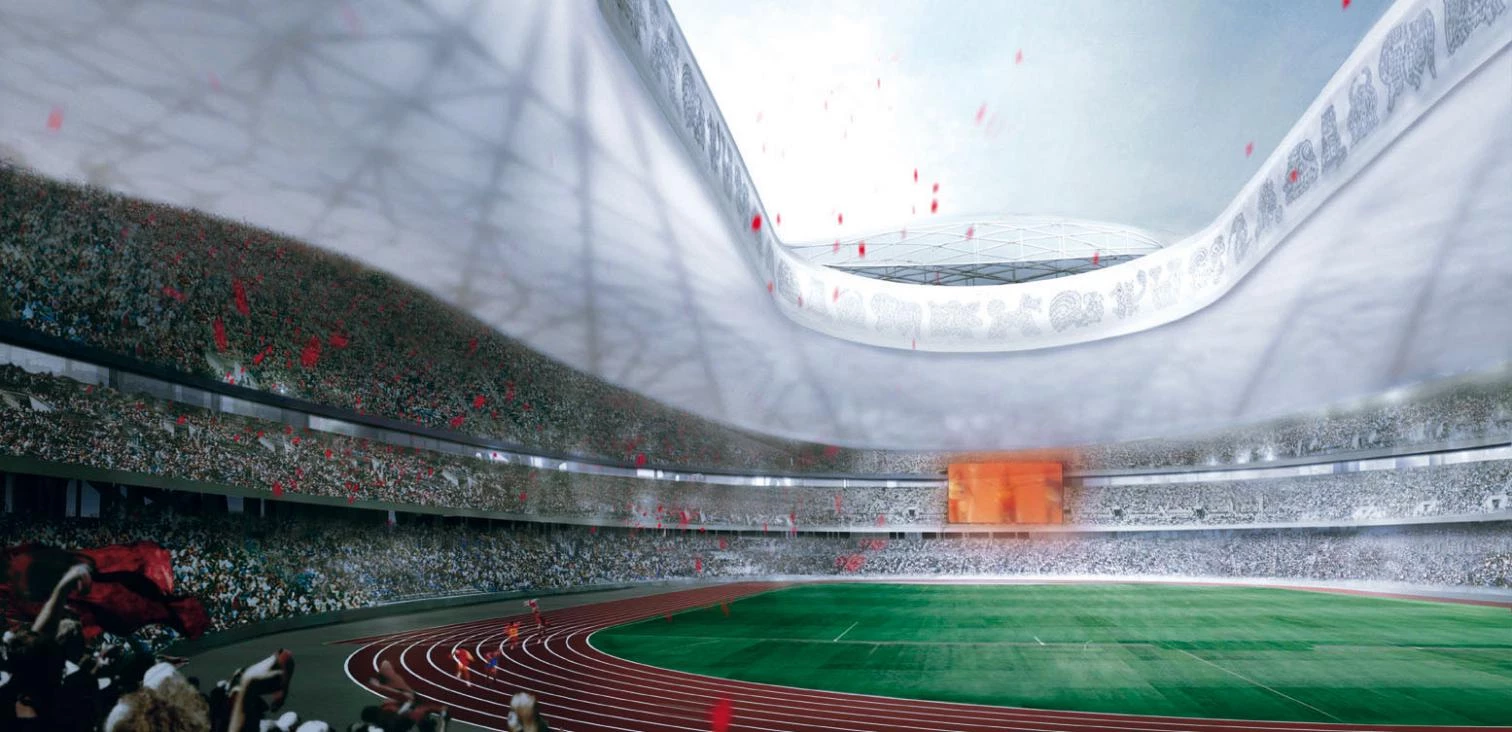

Emblem of the 2008 Games, Beijing’s Olympic Stadium has been conceived as a receptacle of collective celebration; the bowl, with a mesh shaped steel structure, is enclosed by cushions of ethyltetrafluoretylene.

Stretching the parallelism a bit, the three successive stadiums could even serve to illustrate the three volumes of Spheres. Basel’s St. Jakob Park, with its cushions of polycarbonate that give it the look of an embryonic morula, would perfectly represent the microspherical themes of the first volume, dedicated as it is to molecular bubbles of intimacy from the amniotic cavern of the maternal womb –very fitting, indeed, for the football club of their own city, a modest team that this year has made it to the final phase of the European Champions’ League. For its part, Munich’s Allianz Arena, with its translucent chromaticity and its padded airship profile, ties in with the historical and political subject matter of the second volume, where celestial and terrestrial globes are used to describe the process by which the planet is colonized by economic or ideological empires – rather appropriate for a public icon, financed by an international insurance company, which is to be the venue in 2006 of the World Cup of the earth’s most popular sport. Finally, the National Olympic Stadium of Beijing, with its tangle of steel and its aleatory padding of ethyltetrafluoretylene, could efficiently illustrate the polyspherical universe of the last volume, which describes the fluctuating, labyrinthian structures that Sloterdijk calls foams, and whose amorphous, changing proliferation expresses at once a nostalgia for a lost center and “the modern catastrophe of the round world” – a pertinent metaphor for a totalitarian Titan slated to celebrate the 2008 Olympics in a shaken basket that combines the unanimous fervor of the multitude and the random convulsions of the times.

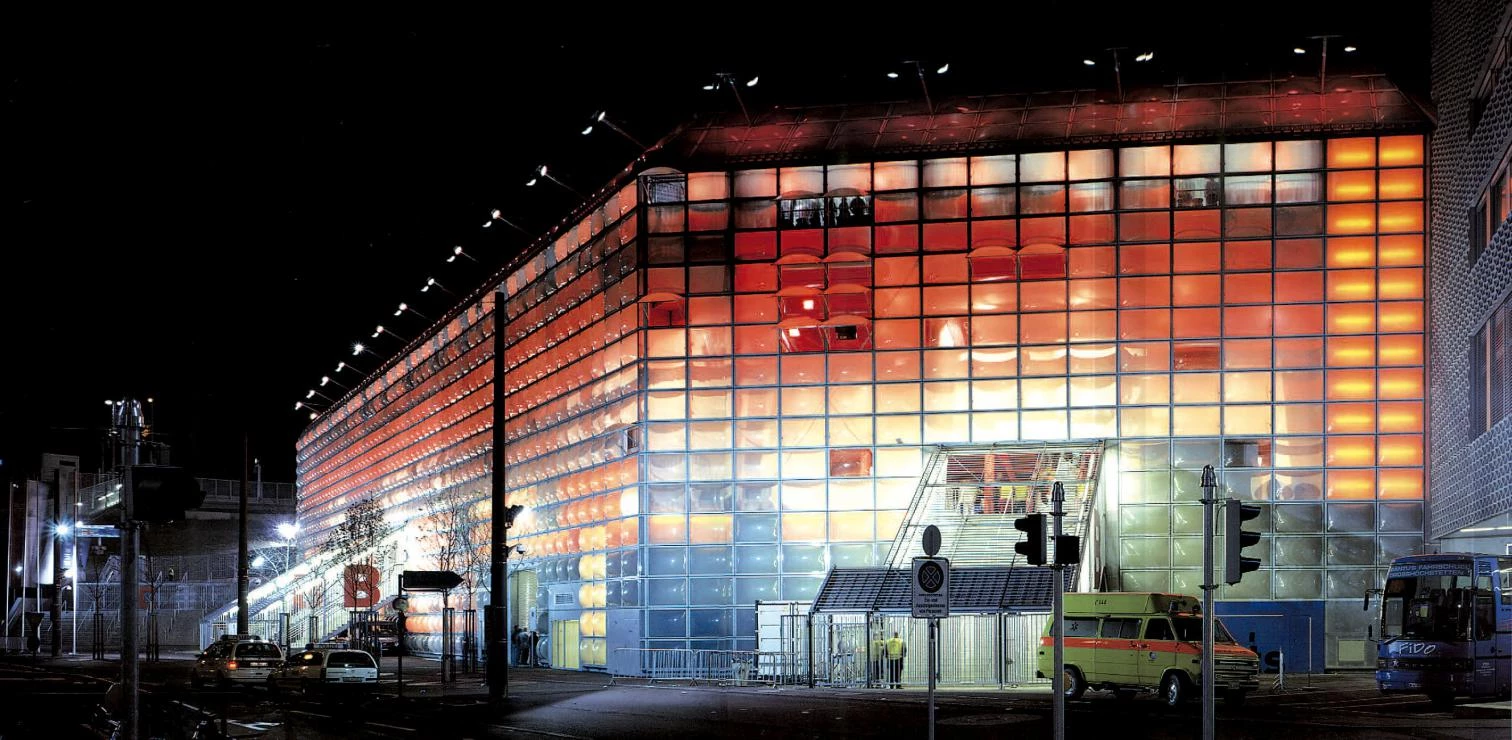

Designed before the Asian project, the remodeling of the Basel stadium (below) and the Munich Allianz Arena also try to monumentalize the public realm, creating luminous urban landmarks.

Beyond these excessive echoes, Herzog & de Meuron share with the author of the Critique of Cynical Reason the conviction that “life is a question of form,” an inclination to think of the human being from the viewpoint of spatial experience, and the intuition that the fading of the idea of womb and shelter, brought on by the loss of the protective cosmic shell of old models of the universe, calls for a new way of designing and thinking that reconcile the intimate with the global. Certainly St. Jakob Park is a cosmetic job of a work in progress where bulging skylights resembling those of the Prada store in Tokyo are used to fabricate a soft and translucent facade that by night theatrically reveals the violent red of the grandstand’s extrados; but this oriental lamp is also a deep red tribute to a sport institution that contributes to the emotional identity and informal sociability of the European city that constitutes the personal sphere of its authors. The Allianz Arena is an instantaneous icon, a fortunate idea of pneumatic imagery and changing color that enabled them to carry the day in the competition, but this luminous symbol of globalization at the service of a finance multinational and a mediatic sport is also a recipient of singular emotions and a spherical vessel of collective interaction. The Olympic Stadium of Beijing, finally, is a brilliant aesthetic and structural challenge whose artistic and technical daring was bound to impress the jury, reaping for the Swiss partners the largest and perhaps most decisive commission of their career; but this memorable tangle of steel hovering over grass and grandstand is also a nest offering ritual shelter, in strange intimacy, to the public sphere.

Global Greenhouse

Herzog & de Meuron have always been given to collaborations and mutual learning. For the Beijing project, they have resorted to the aesthetic assessment of Ai Weiwei, a distinguished artist and exhibitions curator based in the city, and the engineering expertise of Cecil Balmond, the Ove Arup director who has become a fixture in architectural high competition through works carried out for people like Koolhaas, Libeskind, Siza or Kulka –with whom, incidentally, he designed another tangled and stochastic stadium drawn in space in the manner of Julio González or the Tápies of Núvol i cadira. In view of the results, one would have wanted the third collaborator to be Peter Sloterdijk, considering that the philosopher’s concern with “how the human being designs architecture from the security of existence” connects subterraneously with this choral precinct that nestles vulnerable individuals who have broken the metaphorical shell of religious or magical thought: the stadium of the Basel architects mysteriously materializes the global greenhouse of the Karlsruhe thinker, the “domes and artificial skies” under which the gardening humanity seeks refuge from the catastrophe that is devastating the physical and moral atmosphere of our world. Paradoxically, the disaster that is currently paralyzing Beijing with its viral threat contaminates the air with the risk of contagion that rules out collective encounter, while breathing a new transparency into the ambit of politics and social communication. Sloterdijk, who defines himself as a theoretical immunologist and who dedicated his penultimate book to the atmospheric terror of toxic gases, radiations, and microorganisms, would do well to study this double epidemic, at once biological and semantic: an accident that by confronting viral microspheres and social macrospheres represents our times with the same mix of monumentality and intimacy as Beijing’s stadium-nest.[+][+]