The Good Death of Miguel Fisac

Miguel Fisac, a master of long career that combined aesthetic refinement and rich technical imagination, passed away in Madrid on day 12 of the month.

He had prepared it for years. Miguel Fisac orchestrated the farewell ceremony like a final project. He had gone about relinquishing his things and created his foundation, transferred his archives to Ciudad Real, given final instructions, and even written his ‘poems to good death,’ all this serenely leading to his luminous demise in the Cerro del Aire at dawn on a Friday in May. In the house that he built half a century ago for Ana María, accompanied by the woman with whom he shared his long life, this giant of Spanish architecture left our world with the placid resignation that seems to be reserved for believers in the other one. Fisac resigned from Opus Dei shortly before marrying in 1957, but his public disagreements with the institution that he had helped found never affected his religious convicions. This made him await death with the equanimity and grace of the faithful.

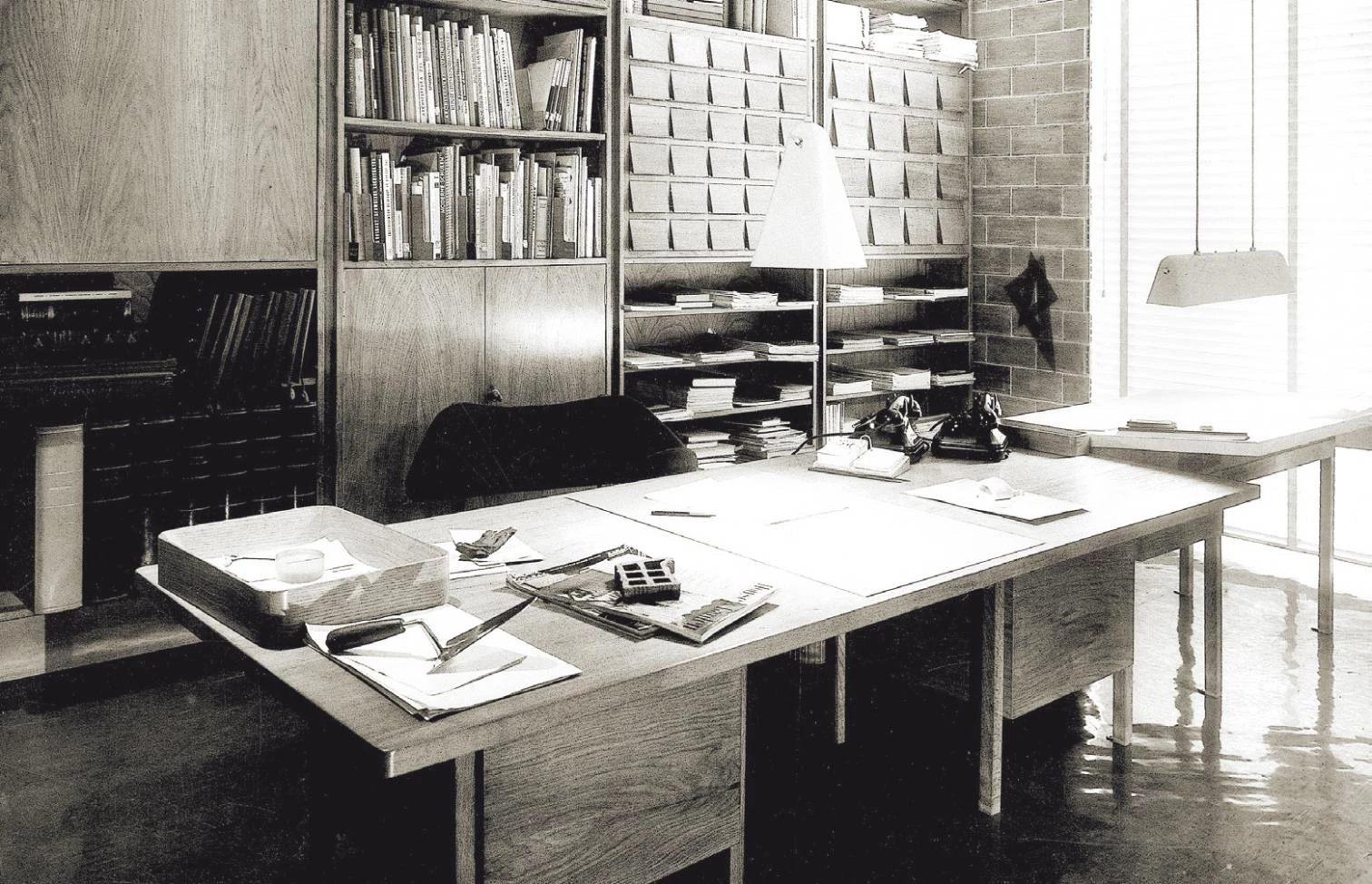

The architect’s office in his first professional studio, with a trowel and a brick section of his own design.

Architects survive through their works, and Fisac’s rich harvest of projects and patents ensures that the products of his genius will live on. Born in 1913 in Daimiel, La Mancha, he graduated in 1942 in Madrid to become an architect with a fertile technical imagination, one gifted with both sculptural talent and mechanical inventiveness. His career spanned six decades, stretching from his beginnings in postwar Spain to works completed already in the 21st century, and despite an essentially consistent lifework we can divide it into three differentiated phases that coincide with actual periods of the country's political and economic evolution: the autarky of the 40s and 50s, the development of the 60s, and the transition of the 70s and 80s.

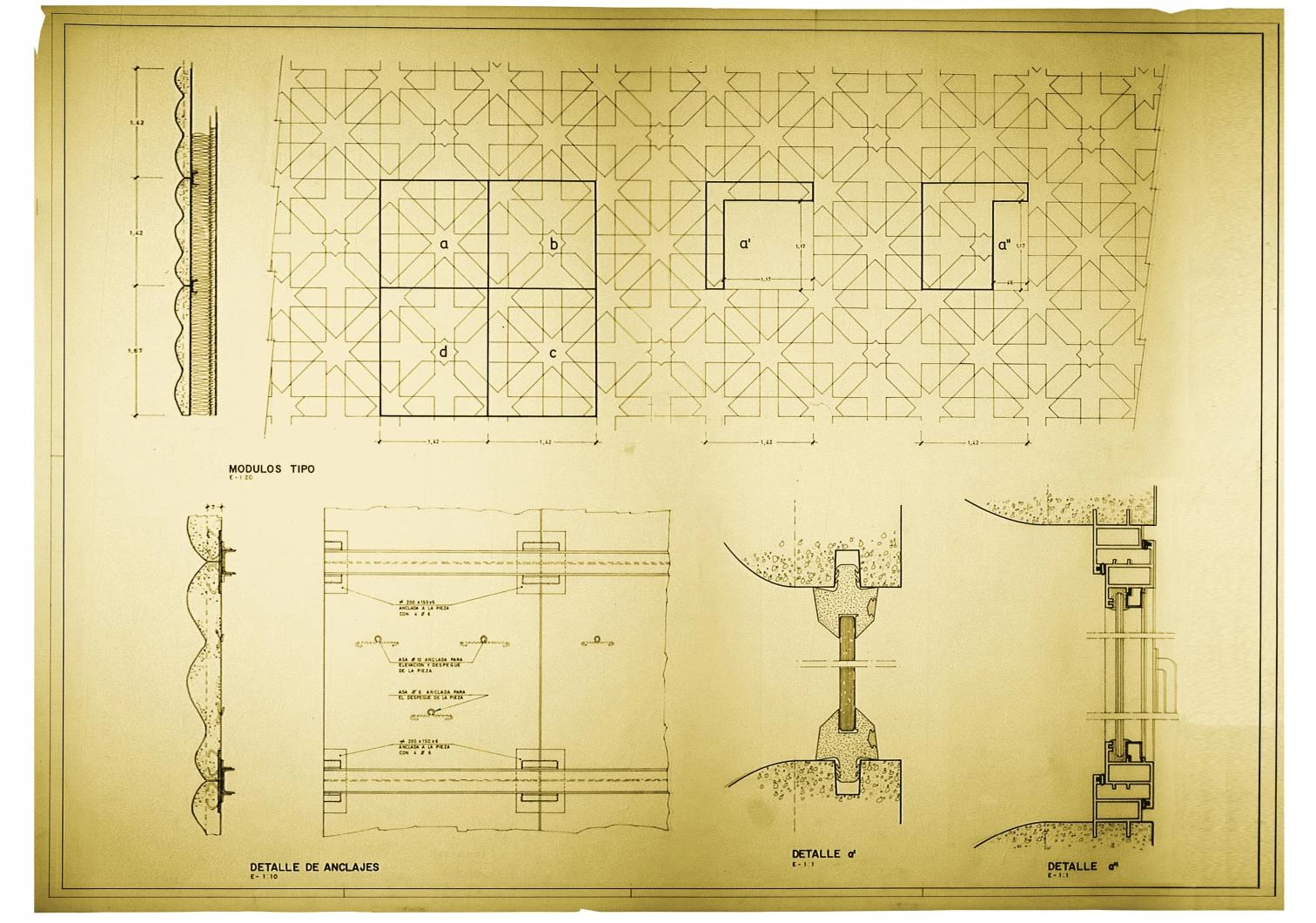

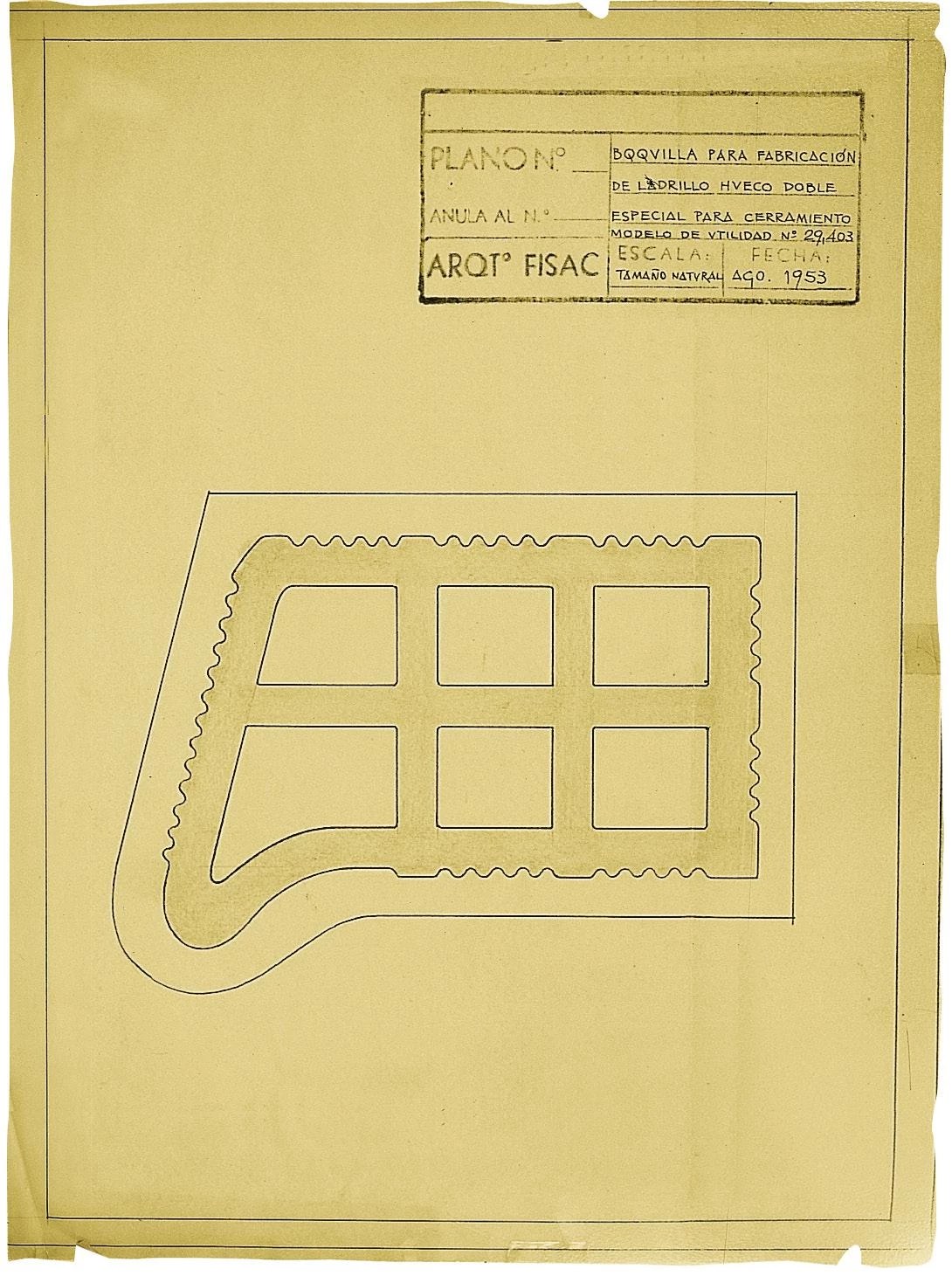

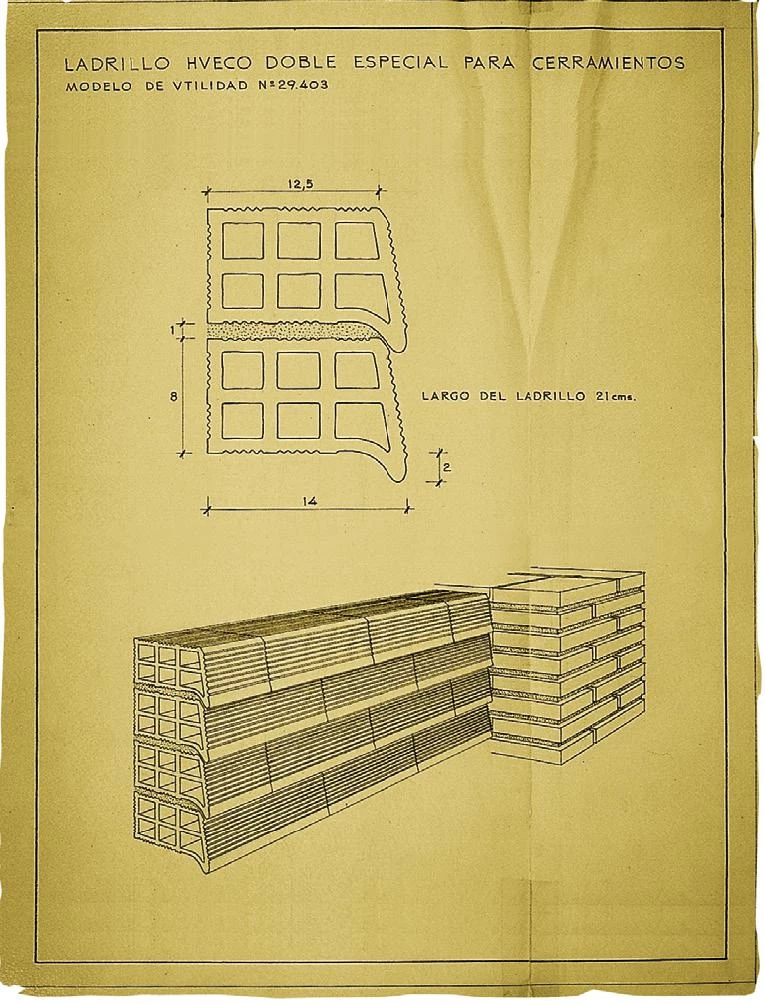

During his initial period, Miguel Fisac develops his technical ingenuity in the field of brick, inventing a piece with an overhang that keeps water out of the joint, used for the first time in the Ramón y Cajal Institute of Microbiology.

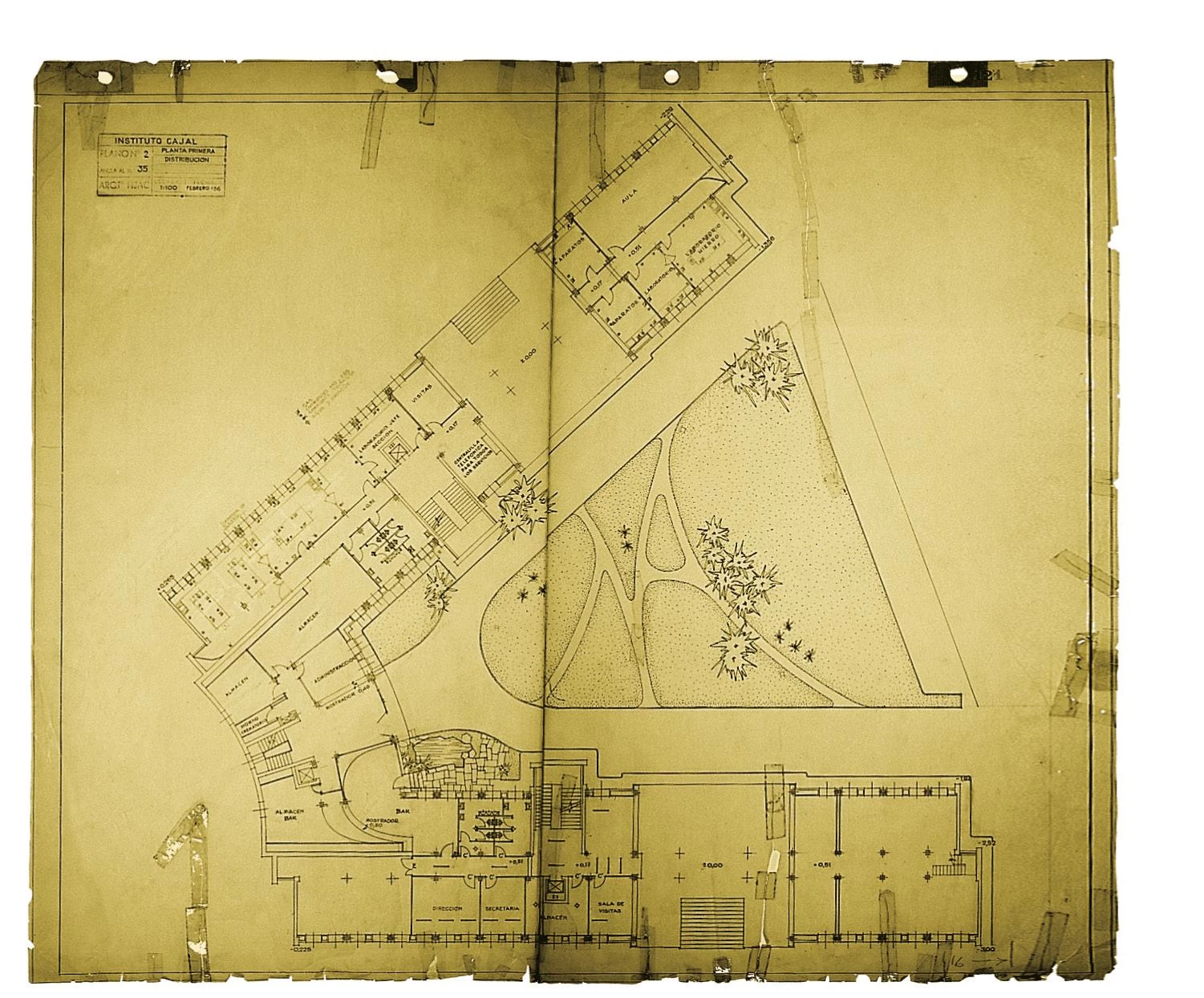

The first period has for a setting the mythical Colina de los Chopos, where the Higher Council of Scientific Research (CSIC) commissioned Fisac to complete an acropolis of knowledge initiated in the republican years, and which the imperial dreams of the winners of the Spanish Civil War wanted to tinge with classicist and Catholic monumentality. So it is that we have the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, the main building of the CSIC, and the stone porticoes that give access from Calle Serrano to this city of God and Science. But the restless traveler in Fisac soon distanced himself from such solemn rhetoric, and his Scandinavian experience of 1949 toned down subsequent works with empiricism, as much in the field of research and education – with the Instituto Cajal in Madrid and the first of a nationwide network of vocational education schools, the latter in his hometown – as in that of religious architecture, which reached unprecedented heights with the building for the Dominican order in Alcobendas.

Fisac’s second phase is linked to his structural experiments with concrete ‘bones,’ used as beams, pergolas, and latticeworks in innumerable projects, from the Made Pharmaceutical Laboratories or the spectacular span of the Center for Hydrographic Studies to the Parish of St. Anne, the IBM building on Paseo de la Castellana or the Garvey Winery in Jerez, a bodyof works that vigorously portrays the technical and social optimism of developing Spain. Also from the 60s is the Jorba Laboratories tower, built with hyperbolic paraboloids of concrete by the Barajas highway, known as ‘la pagoda,’ the 1999 demolition of which sparked a heated public debate.

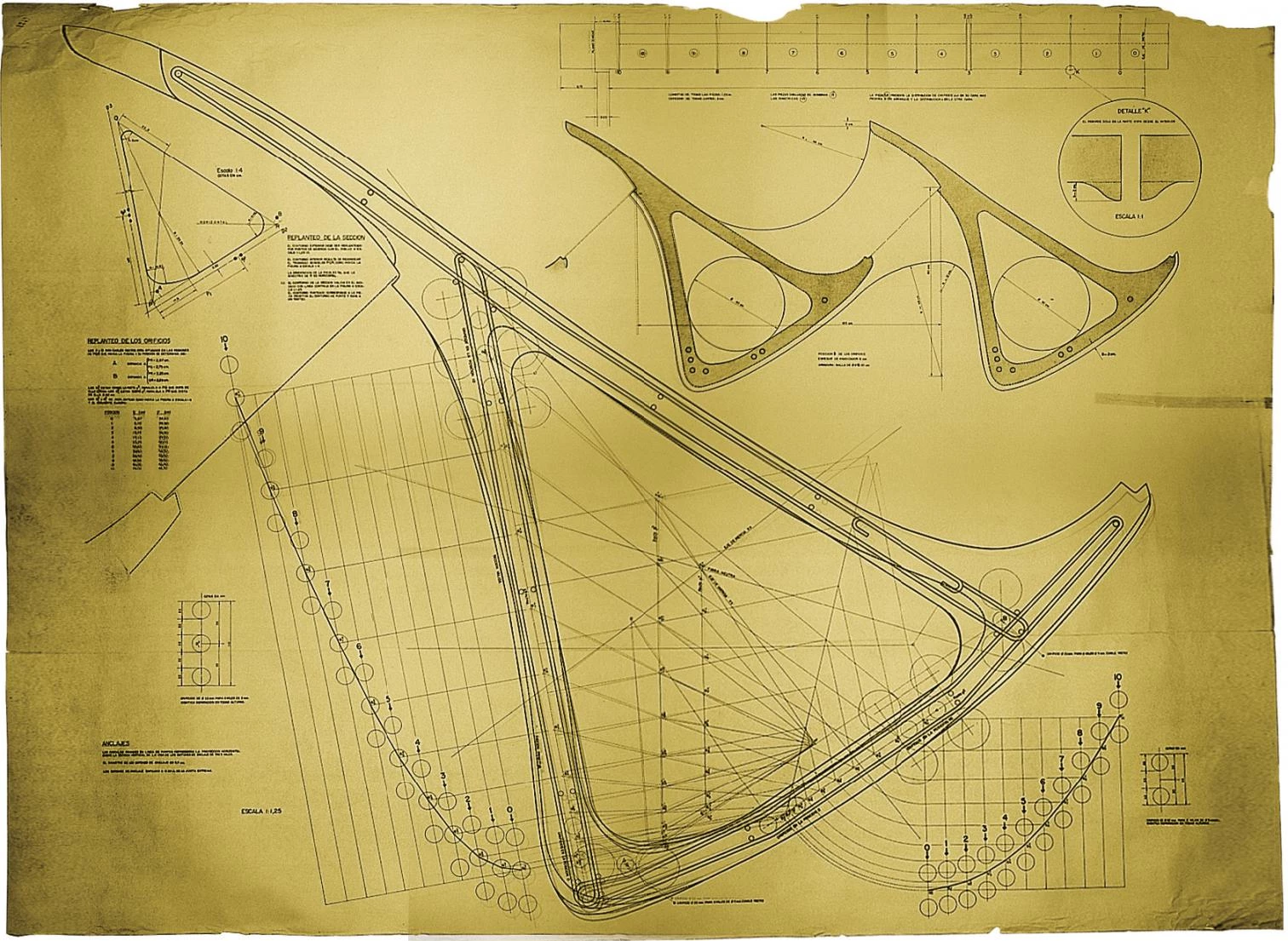

In his second period, the the architect carries out tests with post-stressed concrete that produce his famous ‘bones,’ hollow beams that appear first in the Made Laboratories and in the Center for Hydrographic Studies.

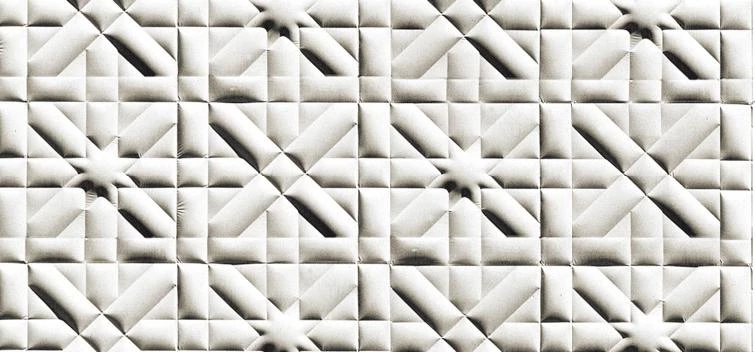

The third and final chapter of Fisac’s work is also the most misunderstood, because his fascination with flexible formworks, which give concrete a softened look, invited scant appreciation among colleagues and critics, and the architect was pushed to a professional background, a relegation even more notorious as it followed three decades of continuous and unanimous success. It was with this technique of flaccid walls that he built the Mupag Rehabilitation Center, the Hotel Tres Islas in Fuerteventura, the Parish of Our Lady of Altamira and the Social Center of the Hospitable Sisters, besides his own studio in the Cerro del Aire and his house in Almagro, domestic realms where he lived as a recluse during his long journey through the desert: an exile that happily came to an end in the 90s with a shower of honors and other gestures of public recognition, but also with the discovery of his figure by international critics, for whom the architect’s concrete ‘bones’ and flexible formworks represented a technical and aesthetic adventure connected to the material and tactile concerns of the latest generations. It is through his influence on these generations, as well as through the solid durability of his works, that Miguel Fisac’s inquisitive, demanding, and lucid spirit will stay on in our midst.

The third stage of Fisac’s oeuvre is characterized by the flexible formworks, a surface treatment of concrete that gives it a cushioned appearance, employed, among other buildings, in the Parish of Our Lady of Altamira.