Sudden Beauty

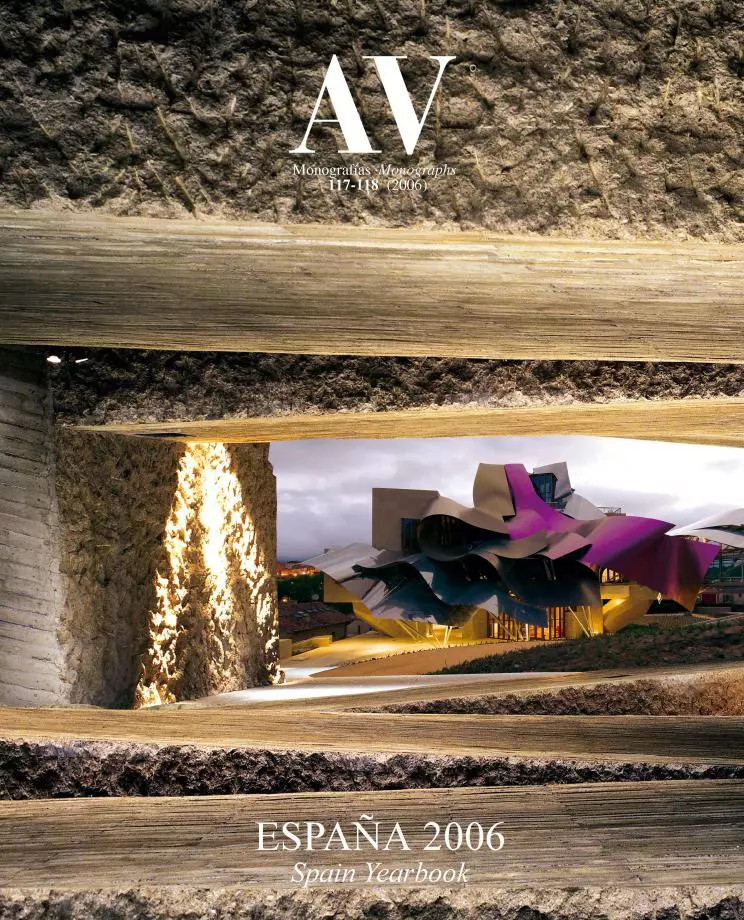

The opening of the Cottbus library marks the start of an ‘annus mirabilis’ for the Swiss studio H&deM, who also present two museums, a stadium and a perfume.

Algae, vin chaud, and tangerine are among the ingredients of Rotterdam, the perfume produced by Herzog & de Meuron to celebrate the exhibition of their work in the Dutch city. The Olfactory Object, as the architects call it, contains hashish, patchouli, and Rhine water, the river that connects Basel to Rotterdam. It is being distributed in a limited edition of 1,000 15-ml bottles. And its strong scent sticks to the skin as tenaciously as images of their works stay in the retina. Jacques Herzog had for years been talking about creating a perfume that would bring to mind “oil paint, wet concrete, or hot asphalt on which it has rained,” fascinated as he was by the capacity of smells to store memory and evoke past experiences or spaces, “almost like an inner film”. The classrooms of our childhood, an old kitchen, or a church during mass are among the places that would be conjured by their olfactory objects, the first of which has been materialized on the occasion of the Netherlands Architecture Institute exhibition, which under the title Beauty and Waste presents a formidable collection of objects, texts, and models illustrating the creative process of the Swiss duo.

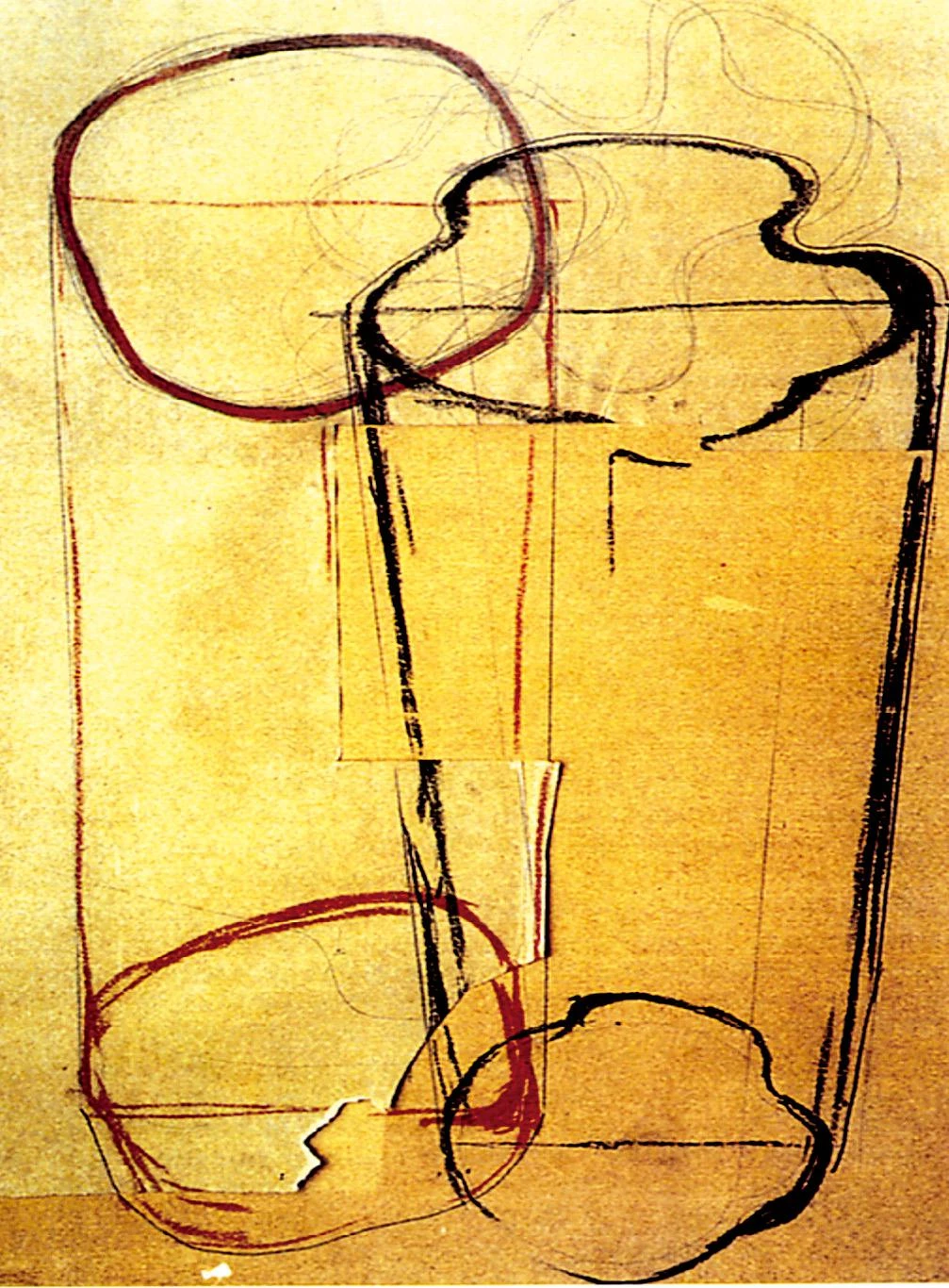

The glass skyscraper of Mies and the Savoy vase of Aalto are antecedents of the wavy plan of Cottbus.

Beauty is not a word used frequently in the art and architectural criticism of our times, but it suits this obstinate exploration of aesthetic emotion that leaves in its wake such a large residue of spoils, failed attempts, and abandoned experiments: wastes of progress in penumbra that advances with setbacks and losses to produce objects of such exact perfection as to seem effortlessly delivered. Like the light elegance of the leaping athlete belying the painstaking preparation behind the movement, the assertive naturalness of the works of Herzog & de Meuron is such that one does not suspect the meanders and mazes of the road taken, documented in Rotterdam through a multitude of discardings that stress the protractedness of the process. In this garden of forking paths, the architect feeling his way in the foliage is once in a while helped by a flash of lightning, and such glare in the dark of night is what some call inspiration.

The library, whose profile is blurred with an undulating perimeter of glass engraved with an abstract pattern, contains a sequence of floors interrupted by straight cuts, generating spaces of great complexity.

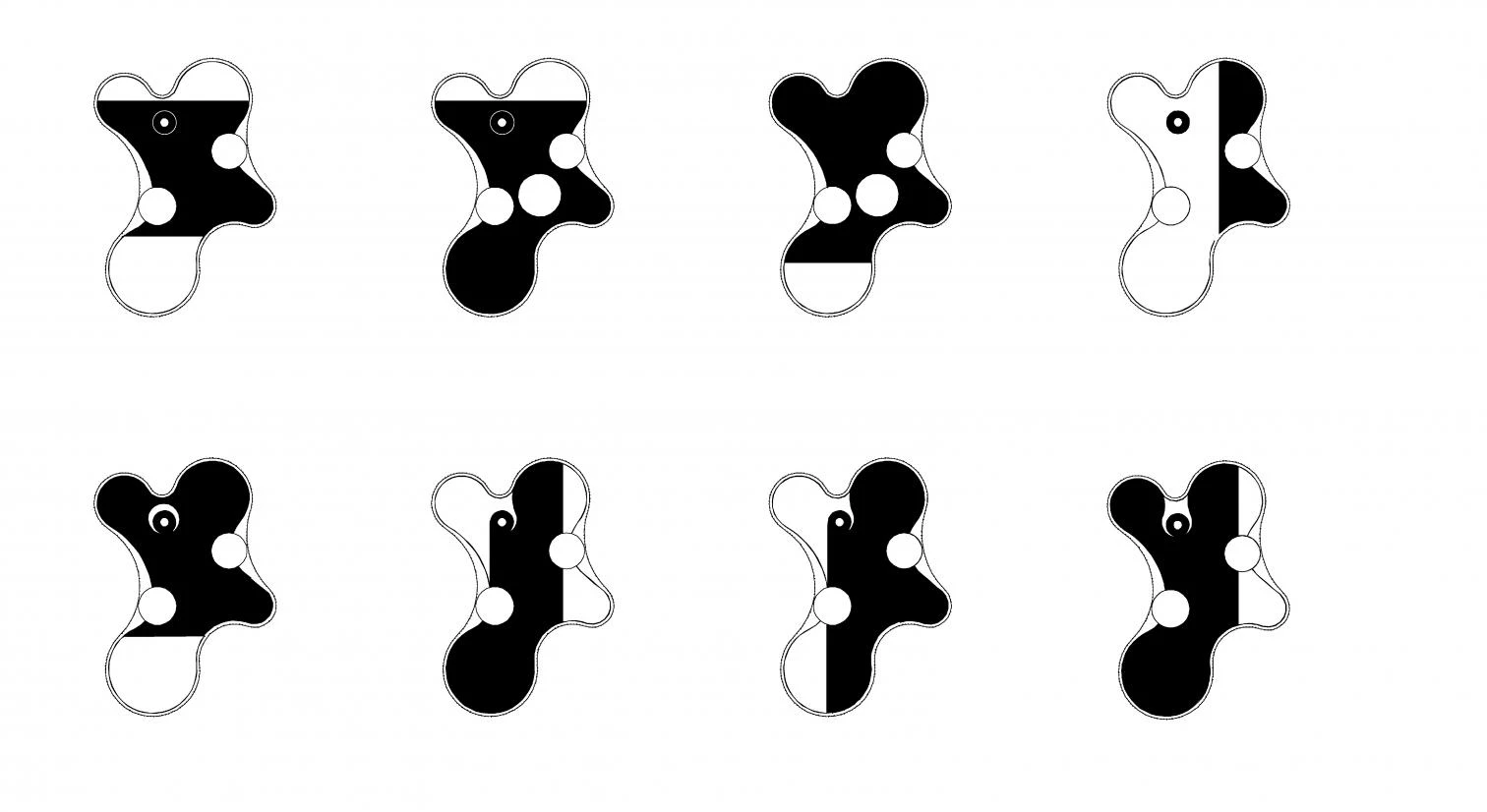

This is exactly what happened in 1997, when, while designing Ricola’s marketing offices (their third project for the manufacturer of herbal candies), their sketches of compact structures with pitched roofs suddenly yielded a star-shaped plan with a transparent perimeter, dissolving the volume in the surrounding vegetation – an unusual proposal that would later be stretched to a whole series of fractured projects. It also happened in the work that is to open now, a university library in an East German town close to the Polish border. The studio of Herzog & de Meuron won the 1994 competition for this commission with a project of prisms, their facades covered with inscriptions, that recalls their library in Eberswalde (another university facility in old East Germany, designed the same year), but would eventually build it with the ameba-shaped floor plan conceived in 1998 – an extrusion of the expressionist curve that would likewise have abundant progeny in the production of the office. But, in the end, both the star and the ameba appear in the regular pattern of everyday work as flotsam of the shipwreck of history, intuitions rescued from past fortunes that rise to the surface of awareness to keep us afloat, more than as ecstatic gleams in the dark forest of mystics.

The exterior of the library is decorated with a monocrome motif based on typographical elements, whereas the interior is lit up with acid colors that underscore the helicoidal shape of the spiral staircase.

The undulating perimeter of the Cottbus library is of course meant to make it unique, so that it can serve as a landmark and an emblem of renewal in a campus built in 1945 with buildings characterized by disciplined dimensional and material homogeneity. Nevertheless, its fluid form – defined by a curtain of glass on which an abstract pattern of typographical origin is engraved, rendering the sculptural volume immaterial by making its organic outline disappear in the sky – does not come from any overwhelming emotion or random caprice of the architects. Rather, it emerges from an eminent lineage of crystalline curves that come from the glass skyscraper of Mies van der Rohe – the mythical theoretical project of 1922 – and stretches on to the Barcelona Trade towers erected by Coderch in 1968-1973 or the Willis Faber Dumas building raised by Foster in 1971-1975, passing through the inevitable episode of the Aalto waves that so admirably sum up the vases designed for the Savoy restaurant in 1937, and which became symbols of lake-dotted Finland.

Inside the glass membrane, the nine floors of the library are organized around cylindrical communication cores, and each of them is cut by a straight line in such a way that no two are alike and none of them takes up the whole area. The result is a wide variety of spaces and reading rooms with different heights and degrees of privacy: an arrangement the architects call heterotopic and non-hierarchic – predictably to counter what could be called the bureaucratic homotopy of the postwar socialist campus – and that in its contrast between the pseudopods, nuclei and digestive vacuoles of the cell-like plan and the perpendicular precision of the cuts uses a very Aaltian compositional device, albeit interpreted here with a playful randomness and jazzy rhythm that gives no hint of the placid movement of the exquisite skin, whose monochromatic and translucent subtlety is, by the way, not easy to reconcile with the chromatic frenzy of some of the interiors.

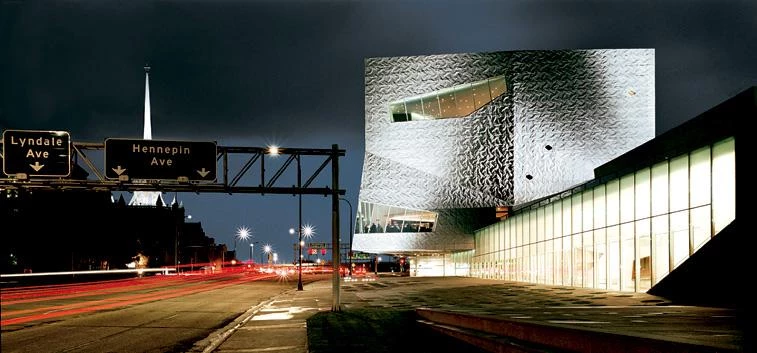

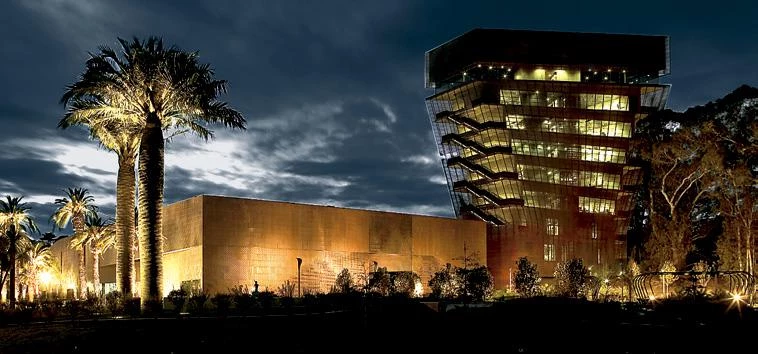

In this same year, the Basel studio completes as well two museums, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the new De Young Museum in San Francisco (above), and a stadium, the Allianz Arena in Munich (below).

A work initiating a hectic sequence of openings (the pneumatic dirigible of the Munich stadium, the Allianz Arena, and two important American museums, namely the expansion of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and the new De Young in San Francisco), the Cottbus library brings to the fore architecture’s relationship with formal innovation and aesthetic originality, a theme that is a must in any commentary on the work of a studio that, after carnival beginnings with Beuys in 1978, has always collaborated with artists – from the projects done with their Basel neighbors Helmut Federle and Rémy Zaugg to the recent works carried out with Adrian Schiess or Ai Wei Wei, passing through their constant relations with photographers Margherita Spiluttini and Thomas Ruff – and often built for institutions or clients of the art world, the milestone here being inevitably the Tate Modern in London.

In an extensive conversation with the photographer Jeff Wall, who incidentally will from May to September be running a show in the Schaulager of the Swiss partners, Jacques Herzog addressed these questions with abrasive lucidity, recognizing his debt to the romanticism of Novalis or the cloud drawings of Goethe and expressing the incompatibility between his image-loving sensuality and the protestant iconoclast fervor that nourishes artistic abstraction, but also admitting his respect for the ‘ordinary’, normative architecture of Haussmann or Hilberseimer, which in our days is manifest in the repetitive regularity of China’s new cities: “The problem for architecture today is not lack of freedom but freedom! Today our designs look much more spectacular and nobody can criticize us for lack of inventiveness or richness of form. Actually the problem is the richness itself, countless variations that flood the world of architecture and art, and generate a kind of blindness. The problem, as always, is to escape the tyranny of innovation”. Thus spoke the author of the Cottbus library and the perfume Rotterdam. Listen to him.