At the edge of the gigantic sea, his clothes left in a pile, his arms hugging his shivering body, a frail, tiny figure wondered whether to take the plunge. In an immense plain, under a huge black cloud, a woman in a sunhat furiously pedalled her bicycle, with its basket of precious vegetables, towards some distant home. Amid an infinity of fir trees two ant-size cyclists almost met, but their paths diverged before contact. In a landscape of rampaging lushness and glorious views a pipe-smoking painter worked at his easel. His human subject, insignificant in the long grass, called “Remember not to forget me!”

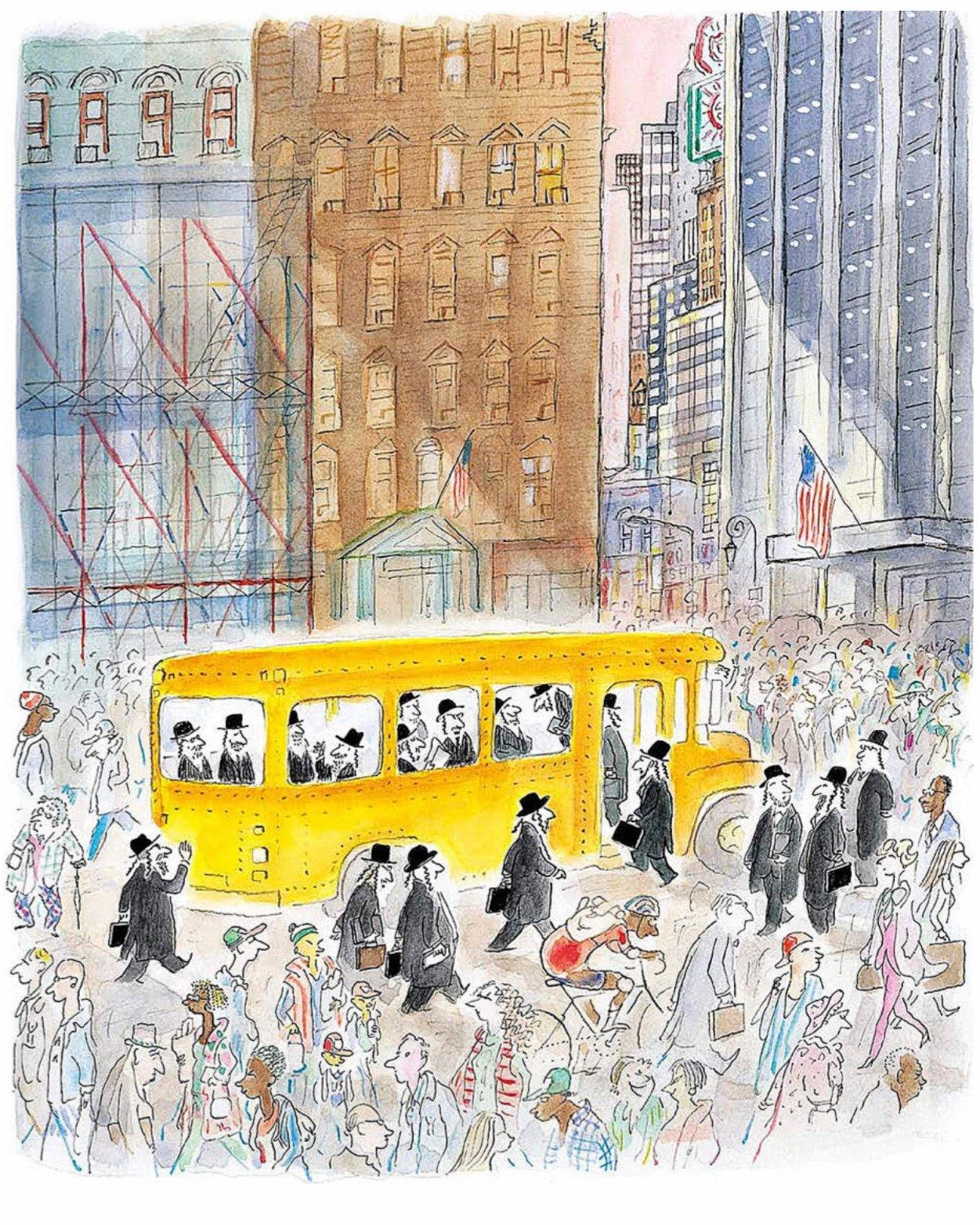

In cityscapes—the tall grey buildings and mansard roofs of Paris, the massed skyscrapers of New York—the proportions were the same. Here the human ants often moved in crowds, through the rainy streets, into opulent concert halls, towards political rallies, usually in the same direction. Yet in the city, too, they broke away and became solitary among the enormous towers. On a flat roof, a little girl jumped a skipping rope. In one lit window, a trainer coaxed a tiger through a hoop. From one balcony, a couple leaned out dangerously to catch the crescent moon through a canyon of high walls. In an immense lamplit colonnade, a furtive tuba-player smoked behind a column.

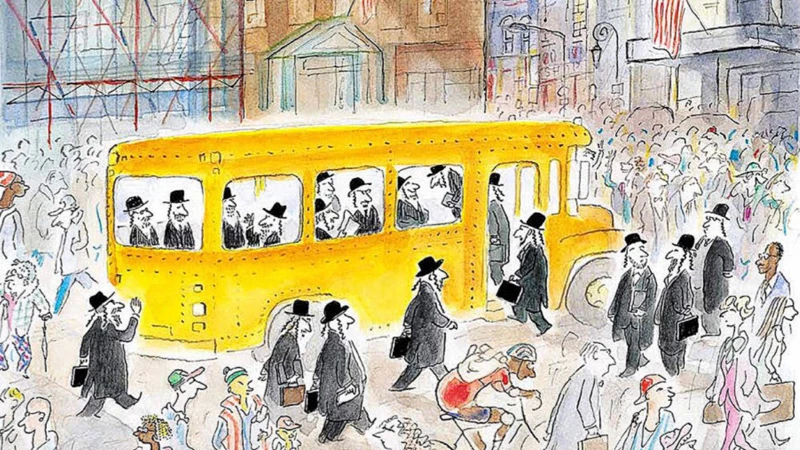

The Economist: Jean-Jacques Sempé was an unparalleled observer of the human condition