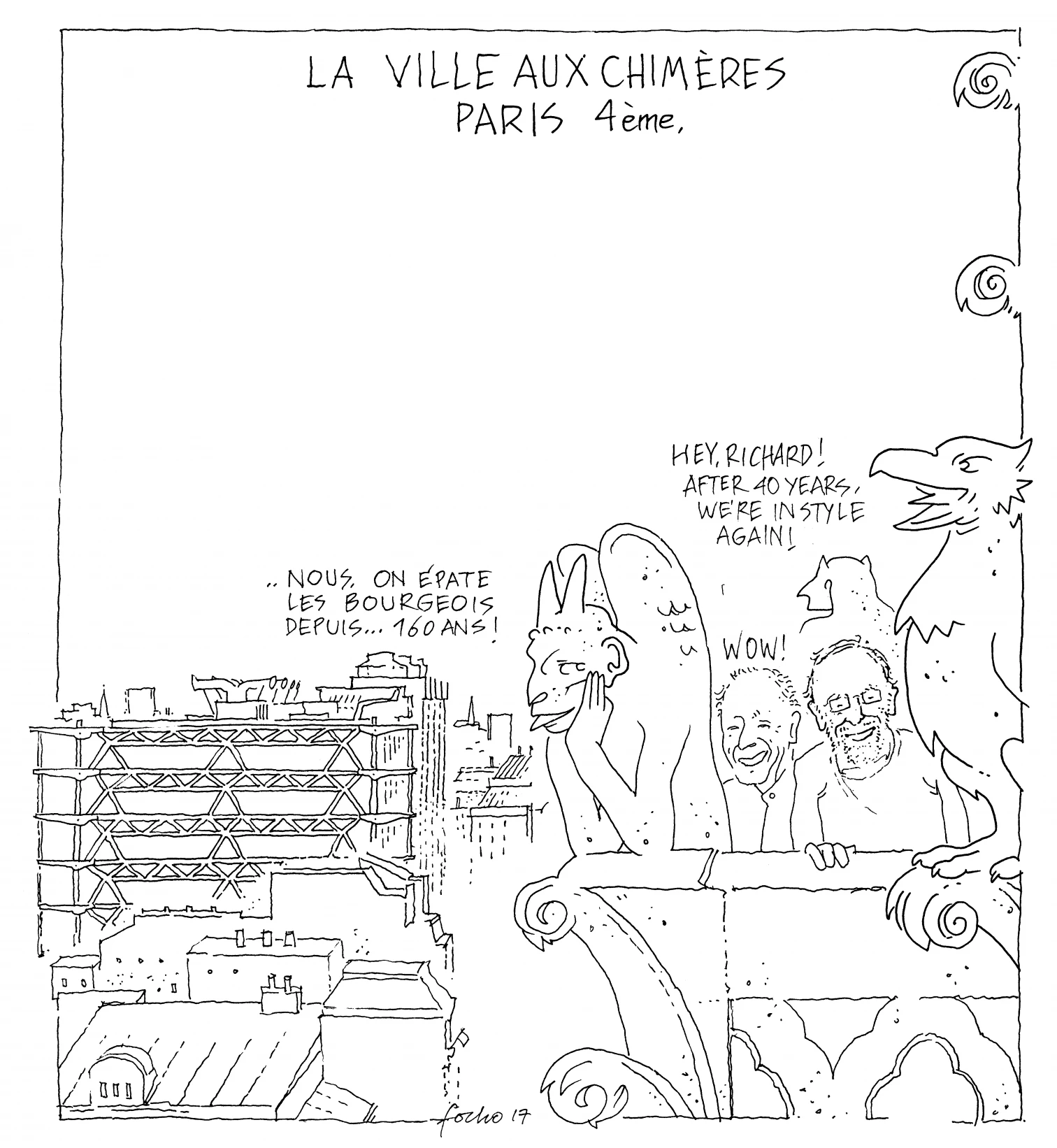

It has been four decades now since the world of architecture, and of culture in general, was shaken by the irreverent forms of the Centre Georges Pompidou, a huge artifact, at once powerful and ingenuous, that seemed to have landed right in the heart of Paris like a spacecraft in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and which many also saw as Cedric Price’s Fun Palace finally materialized. However, beyond these references which link the Beaubourg project to the persistent technological fantasy of modernity, the building was an intelligent and daring political gamble of President Georges Pompidou, the very conservative Charles de Gaulle’s right-hand man, who had personally suffered the disturbances of May 1968 and who, through this major construction promoted by the State, launched an ideological counter-offensive under the protection of a concept that was unquestioned – and in the French case venerated – in western societies: culture. Nevertheless, the techno-expressionist language of the enormous container conceived by a young Italian, Renzo Piano, and a young Brit, Richard Rogers, fabricated for the most part by a German family company, Krupp, and built with the toil of Algerian laborers sparked not a few controversies; polemics which, as with the Eiffel Tower, were vehement but ultimately short-lived. The Pompidou, proudly welcomed by the people of Paris, was perhaps the world’s very first icon of contemporary culture, the same contemporary culture that now seems to be steep in crisis.