In the early 1920s a good review was still worth a fortune and a bad review could end a career. The aura of the great 19th-century critics could still be felt, but much had changed since. If the 19th century was the Golden Age of criticism and the early 20th century was its Silver Age, the decades after World War II might be called the Bronze and the Heroic Ages.

In the 1980s criticism lost almost all of its former influence. It turned into a shadow of itself, lost its bite, became harmless. There are many star architects today, but no star critic. What happened? Has criticism been absorbed by discourse to become the exclusive realm of a handful of writers so intoxicated with French theory as to have become so self-sufficient it can almost do without architectural objects? Has the abundance of statements and interviews by star architects made the critics’ voices obsolete? Have the star architects incorporated criticism into their practices in order to produce and control it themselves? Or is there simply no more time for criticism in a digital age?

Evidently, criticism has not gone for good. We can hear it whispering in architecture schools, we can sense its influence in architectural juries, and we can feel its impact in informal discussions among colleagues at conferences or cocktails. Potentially, criticism is still there. But where can critics work? Every provincial town has the funds to build a new museum by a star architect, but there are only a handful of architectural journals, most struggling to survive. Members of editorial boards look like anachronistic missionaries. They search for new themes, find out about forgotten architects, run after deadlines, printing mistakes, and sponsors. Their journals are understaffed and they are underpaid.

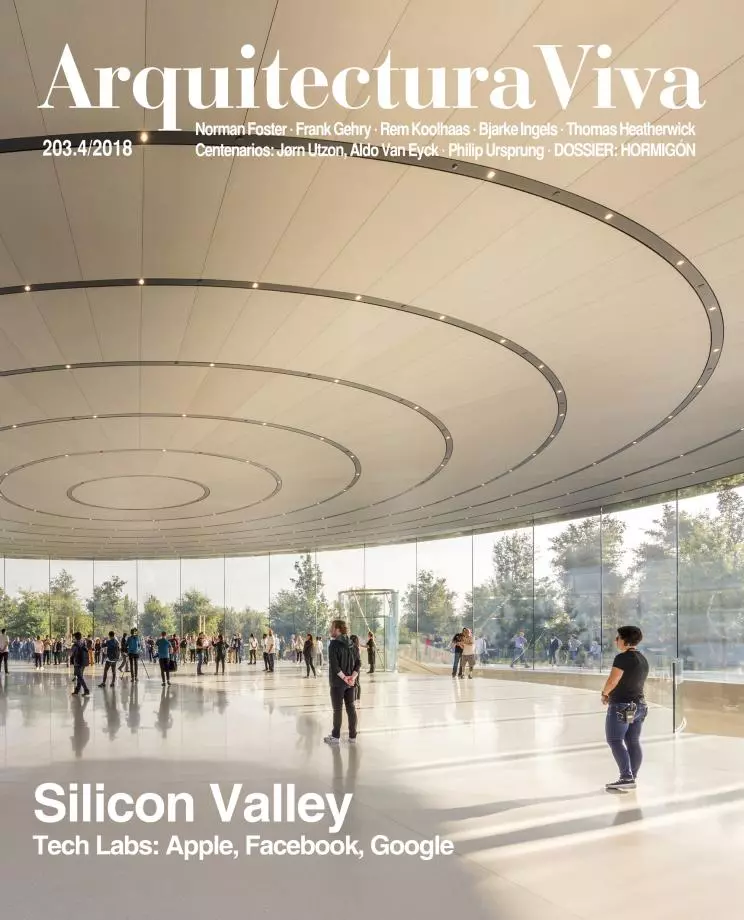

The most successful of these journals look more like monographs than magazines. They contain interviews and statements by the stars and interpretations by historians, but no judgment. They are produced in close association with architectural practices that provide plans and photographs and are involved in the selection of authors. They are well produced but they are basically propaganda. And they are filled with glossy, full-color illustrations, images of newly completed buildings under blue skies.

The glossy image is the very emblem of the decline of criticism. It is much more powerful than words. In such a context, the articles are often little more than long captions. Nobody seems to be concerned that the fee for an article is less than the fee for the copyright of an illustration. And they show us that although we are living at a time that has been labeled the ‘iconic turn,’ there has been no progress in architectural representation. In fact, the flawless glossy photographs are as static and as sterile as the images in the political propaganda of both East and West, past and present.

But the sheer abundance of images is also a good chance for a comeback of criticism. After all, earlier critical movements in history, such as Dada or Surrealism, originated in protest against the smoothness of the cultural sphere, and collage has been a very powerful weapon in deconstructing and undermining the power of propagandistic images. I am quite sure that the renewal of criticism will emerge from the work on images. I am looking forward to the critiques that show us black-and-white images, attack the continuity of the glossy surface, and allow people back into buildings. I am looking forward to the day when a favorable image will be worth a fortune and a devastating image will have the power to ruin a career.

This essay is taken from the book Brechas y conexiones. Ensayos sobre arquitectura, arte y economía (Puente Editores, Barcelona. 2016).