The Future of Technology

A Lynchpin of Connectivity for Africa’s Future

Even in the short time of my involvement as a trustee of the Norman Foster Foundation in this ‘futuristic’ project, the future has become a reality. We all know that technology is moving so fast that we can’t keep apace of developments. But in the case of the Droneport project something else has happened. The combined added value of sophisticated design thinking, the increased awareness of the social costs of inaction in Africa, and the unexpected but welcome collaboration between governments and industry are turning an instinctive concept into a concrete realisation on the ground.

“If you’re a postman, look away now. The future of deliveries is here – and it’s all about drones.” This is how Amazon announced its first trail drone delivery in the United Kingdom in December 2016. Google’s giant parent company Alphabet, with US$35 million from the United States Government, is investing in Project Wing to build the “next generation of automated aircraft that opens up universal access to the sky.”

Meanwhile in Rwanda – one of Africa’s poorest states now experiencing strong growth – it’s already happening. Zipline, a commercial start-up with US funding, is working on drone deliveries to 21 blood transfusing facilities within a 75 kilometer radius, fuelled by a single battery charge. Blood, plasma and coagulants are now being delivered to hospitals across rural western Rwanda, helping to cut waiting times from hours to minutes. According to The Guardian, “Drones may well bring the most exciting potential to marry the real and vast physical challenges of Africa with the digital revolution.”

The development of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) is a synthesis of advanced technology, design, entrepreneurship and social purpose. Unsurprisingly, it matches the integrated systems thinking which defines Norman Foster’s extraordinary 55 year old career as architect, designer, planner and visionary.

For a man who spent much of his life flying and thinking about how to reduce the weight of buildings, the Droneport project is all about grounding, literally and metaphorically. It is about how to ‘make’ a simple, cheap and easy-to-build structure out of materials derived from the earth. It is also about staking the ground for a basic form of civic urbanisation that grows out of and around what will become the quintessential 21st-century micro transport hub – the Droneport.

As he has done before, Foster assembled a team of exceptional thinkers and doers around him. But, I don’t think they have ever been involved in something so small. The reason is simple. The consequences are vast. The impact of delivering urgent medical supplies – and much else – with drones in Africa is truly cathartic.

Jonathan Ledgard, the Africanist who stimulated Foster’s interest in the initiative through his Redline charity, believes that the problem (and the potential) is not limited to Africa. To his mind, approximately 800 million people in the world will lack access to economic necessities and basic health services for the foreseeable future. For the drone system to work, Ledgard argues, it must be cheap and affordable and be positioned at the right price point. Drawing an analogy with the swarms of two-wheelers that criss-cross Indonesian cities and keep the economy going, he sees drones as ‘motorcycles of the sky’. The Droneport, then, will be like a garage-petrol station-supermarket at the heart of evolving population centres. Its civil and economic potential as a ‘social connector’ is significant.

A Future for Africa

More than any other continent on the globe, Africa can benefit from the advances of new technologies and systems which ‘leapfrog’ traditional cycles of development and growth. The facts speak for themselves. Its population will double to 2.2 billion by 2050. The share of Africans living in urban areas will grow from 38% in 2015 to 50% by 2030. But, most people will still be living in informal settlements with little or no access to basic services.

Although there are signs of improvement, life expectancy still hovers at around an average of 50 years (in China and Singapore it’s over 80), and child mortality remains unacceptably high. Alongside improved nutrition and sanitation, mortality rates can be slashed with quick and cost-effective access to medical supplies.

But in Africa, access is the problem. Because of its vastness and preindustrial level of infrastructure, just a third of Africans live within two kilometres of an all-season road. There are no continental motorways, almost no tunnels, and not enough bridges to reach people living in far-flung areas of the continent. In Western Uganda, for example, the extensive mountainous terrain has no tunnels or bridges to speak of, and its mud tracks are battered regularly by torrential rain. Deliveries of goods are unpredictable, slow and expensive. When it comes to medical supplies, the consequences can and are life-threatening.

The World Bank and African Development Bank spend as much as half of their total resources on traditional infrastructure development. Some argue that US$60 billion investment would simply serve to stand still, given the pressure and intensity of population growth. But few believe that this infrastructural catch-up will come close to being able to serve the needs of a surging population at a time when they need it most.

Nonetheless, there are reasons to be positive. Mobile phone technology has already had an impact in Africa, facilitating transactions, improving governance and information exchange, contributing to increased productivity in this predominantly rural continent. In 2004 Vodafone, via Safaricom, had 400,000 subscriptions across the Continent. In 2013 it had 23 million.

Drone technology is likely to have a similar effect on growth and demographics, allowing faster, cheaper and safer forms of connection than slow-to-deliver and costly roads and railways. The Droneport, therefore, has the potential of becoming not only an important component of the supply-chain but also a lynchpin of connectivity for Africa’s future.

This is why the Norman Foster Foundation has pursued the Droneport project. It is much more than just a small airport for small flying objects. It is about ‘making’, it’s about ‘connecting’ and it’s about the civilising impact of infrastructure. Norman Foster has focussed his prodigious energies on designing the simplest possible structure that can unleash wider social, economic and demographic benefits. And the project is, hopefully, about to take off, initially in Rwanda.

Reflecting on the origins of the design of the project, Foster goes back to some of the early inspirations of his career. Apart from indigenous mudbrick structures of sub-Saharan Africa, Foster was always fascinated by the 19th-century Valencian architect and builder Rafael Guastavino, who invented the ‘tile arch system’ based on the traditional Catalan vault to construct robust, self-supporting arches and vaults using interlocking terracotta tiles and layers of mortar. The system was used to great effect in structures across the USA including the Queensboro Bridge and Grand Central Station in New York.

Foster and his close group of colleagues, including some of the world’s most creative engineers, accomplished construction companies and experienced master-builders, were intrigued by the efficiency of this 19th-century solution. They saw the potential of inventing a 21stcentury version of the tiled-arch that could become the basic building block of a Droneport. To be successful, it had to be erected quickly, cheaply and efficiently in locations across Africa without sophisticated machinery. It was important that the construction could be assembled by unskilled labour and, wherever possible, employed local materials including earth.

The technical details are too complex to go into here, but the basic unit of the Droneport is a double curvature vault form which carries its own weight and withstands other loading such as wind or earthquakes. The unit can stand on its own or be assembled as part of a larger complex. Philip Block, one of the lead engineers with John Ochsendorf, wanted to develop “a kit of parts in which all the intelligence is embedded, which is as lightweight as possible, and which can capitalise on local resources.”

Design and Prototype

To enable this process to happen, the design required some significant innovations. The first is a system of steel poles and flexible fibreglass rods that allow the vault’s form to be drawn in three dimensions. A second is the replacement of fired tiles traditionally used in tile-vaulting with compressedearth Durabrics developed by LafargeHolcim. While recognising that the design is still evolving, Ochsendorf confirms that “if the Durabric can be produced locally, then you’re looking at something that is 90% a Rwandan product’, a key objective of the Droneport procurement and construction process.

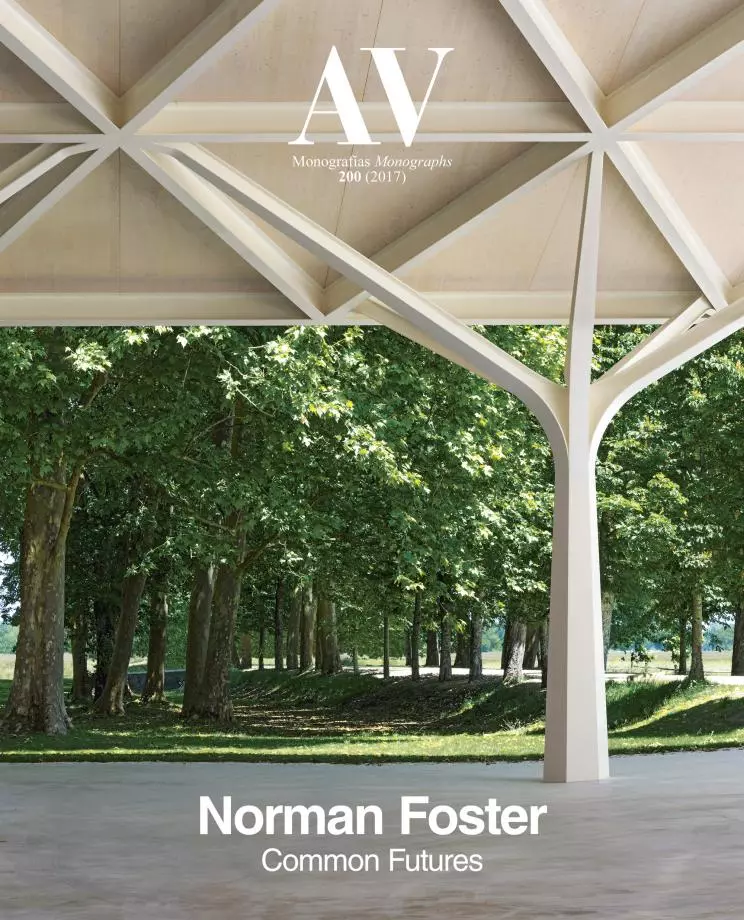

Foster and the team recognised that these early ideas needed to be tested with a real prototype before rolling out the project in Africa. The timely staging of the 15th International Architecture Biennale in Venice in 2016 provided the perfect opportunity. At the cost of US$70,000 a full-size prototype of the Droneport was erected in a unique location next to the stunning 16th-century masonry structures of Venice’s Arsenale complex – a fitting backdrop to this 21st-century reinterpretation of pure architecture. Visited by over 260,000 people, the Biennale has put on display in a concrete and tangible way how the Droneport is constructed, what it looks and feels like. It is to remain a permanent structure from 2016 onwards.

Seeing the completed structure in Venice is transformational. It reveals the authenticity, elegance and simplicity of a design product of the highest order realised with the most modest of means.

But the Droneport prototype does much more than this. It suddenly makes you see that Norman Foster’s initial conception really does have proto-urban potential. You can imagine: three four, five… up to twenty vaulted elements connected together to form an incremental settlement that grows out of and around a point of arrival and departure.

Once a Droneport becomes a reality, one can see that people will gather to collect, deliver and transact under the assembled structures housing different activities: from drone terminal to repair yard, from medical storage to pharmacy, from post-office to market, from meeting space protected from the sun or rain to local school or garage. If, as Jonathan Ledgard has noted, the “price point is right,” these structures and the drone operations do have the potential to support growth, create local employment and contribute to civic life.

In describing this incremental, adhoc process of socialisation, Foster refers not only to the visceral link between transport and human settlements – from Mesopotamian towns on the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates to the emerging Aerotropolis of new Asia – but also to the collective, associational principles of mid-20thcentury architecture of Aldo van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger. It is a project that reunites life-long values with new territories and possibilities of intervention.

The Droneport project is more than the sum of the parts. The Norman Foster Foundation is now working with other agencies and partners to move the project forward in the African continent. Discussion with governments, investors and drone operators are advanced with hopes for the first droneports to be realised in Rwanda within the next eighteen months.

For Norman Foster, the Droneport project “is about doing more with less, capitalising on the recent advancements in drone technology – something that is usually associated with war and hostilities – to make an immediate lifesaving impact in Africa.” It has taken an exceptional level of vision, design ingenuity and commitment to take the project so far. We are very close to seeing that “the future has become a reality.”

Ricky Burdett is a professor of Urban Studies at LSE and a trustee of the Norman Foster Foundation.